Chapter 9 – Center of Mass and Linear Momentum I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Glossary Physics (I-Introduction)

1 Glossary Physics (I-introduction) - Efficiency: The percent of the work put into a machine that is converted into useful work output; = work done / energy used [-]. = eta In machines: The work output of any machine cannot exceed the work input (<=100%); in an ideal machine, where no energy is transformed into heat: work(input) = work(output), =100%. Energy: The property of a system that enables it to do work. Conservation o. E.: Energy cannot be created or destroyed; it may be transformed from one form into another, but the total amount of energy never changes. Equilibrium: The state of an object when not acted upon by a net force or net torque; an object in equilibrium may be at rest or moving at uniform velocity - not accelerating. Mechanical E.: The state of an object or system of objects for which any impressed forces cancels to zero and no acceleration occurs. Dynamic E.: Object is moving without experiencing acceleration. Static E.: Object is at rest.F Force: The influence that can cause an object to be accelerated or retarded; is always in the direction of the net force, hence a vector quantity; the four elementary forces are: Electromagnetic F.: Is an attraction or repulsion G, gravit. const.6.672E-11[Nm2/kg2] between electric charges: d, distance [m] 2 2 2 2 F = 1/(40) (q1q2/d ) [(CC/m )(Nm /C )] = [N] m,M, mass [kg] Gravitational F.: Is a mutual attraction between all masses: q, charge [As] [C] 2 2 2 2 F = GmM/d [Nm /kg kg 1/m ] = [N] 0, dielectric constant Strong F.: (nuclear force) Acts within the nuclei of atoms: 8.854E-12 [C2/Nm2] [F/m] 2 2 2 2 2 F = 1/(40) (e /d ) [(CC/m )(Nm /C )] = [N] , 3.14 [-] Weak F.: Manifests itself in special reactions among elementary e, 1.60210 E-19 [As] [C] particles, such as the reaction that occur in radioactive decay. -

Towards Adaptive and Directable Control of Simulated Creatures Yeuhi Abe AKER

--A Towards Adaptive and Directable Control of Simulated Creatures by Yeuhi Abe Submitted to the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Computer Science and Engineering at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY February 2007 © Massachusetts Institute of Technology 2007. All rights reserved. Author ....... Departmet of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science Febri- '. 2007 Certified by Jovan Popovid Associate Professor or Accepted by........... Arthur C.Smith Chairman, Department Committee on Graduate Students MASSACHUSETTS INSTInfrE OF TECHNOLOGY APR 3 0 2007 AKER LIBRARIES Towards Adaptive and Directable Control of Simulated Creatures by Yeuhi Abe Submitted to the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science on February 2, 2007, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Computer Science and Engineering Abstract Interactive animation is used ubiquitously for entertainment and for the communi- cation of ideas. Active creatures, such as humans, robots, and animals, are often at the heart of such animation and are required to interact in compelling and lifelike ways with their virtual environment. Physical simulation handles such interaction correctly, with a principled approach that adapts easily to different circumstances, changing environments, and unexpected disturbances. However, developing robust control strategies that result in natural motion of active creatures within physical simulation has proved to be a difficult problem. To address this issue, a new and ver- satile algorithm for the low-level control of animated characters has been developed and tested. It simplifies the process of creating control strategies by automatically ac- counting for many parameters of the simulation, including the physical properties of the creature and the contact forces between the creature and the virtual environment. -

7.6 Moments and Center of Mass in This Section We Want to find a Point on Which a Thin Plate of Any Given Shape Balances Horizontally As in Figure 7.6.1

Arkansas Tech University MATH 2924: Calculus II Dr. Marcel B. Finan 7.6 Moments and Center of Mass In this section we want to find a point on which a thin plate of any given shape balances horizontally as in Figure 7.6.1. Figure 7.6.1 The center of mass is the so-called \balancing point" of an object (or sys- tem.) For example, when two children are sitting on a seesaw, the point at which the seesaw balances, i.e. becomes horizontal is the center of mass of the seesaw. Discrete Point Masses: One Dimensional Case Consider again the example of two children of mass m1 and m2 sitting on each side of a seesaw. It can be shown experimentally that the center of mass is a point P on the seesaw such that m1d1 = m2d2 where d1 and d2 are the distances from m1 and m2 to P respectively. See Figure 7.6.2. In order to generalize this concept, we introduce an x−axis with points m1 and m2 located at points with coordinates x1 and x2 with x1 < x2: Figure 7.6.2 1 Since P is the balancing point, we must have m1(x − x1) = m2(x2 − x): Solving for x we find m x + m x x = 1 1 2 2 : m1 + m2 The product mixi is called the moment of mi about the origin. The above result can be extended to a system with many points as follows: The center of mass of a system of n point-masses m1; m2; ··· ; mn located at x1; x2; ··· ; xn along the x−axis is given by the formula n X mixi i=1 Mo x = n = X m mi i=1 n X where the sum Mo = mixi is called the moment of the system about i=1 Pn the origin and m = i=1 mn is the total mass. -

Non-Local Momentum Transport Parameterizations

Non-local Momentum Transport Parameterizations Joe Tribbia NCAR.ESSL.CGD.AMP Outline • Historical view: gravity wave drag (GWD) and convective momentum transport (CMT) • GWD development -semi-linear theory -impact • CMT development -theory -impact Both parameterizations of recent vintage compared to radiation or PBL GWD CMT • 1960’s discussion by Philips, • 1972 cumulus vorticity Blumen and Bretherton damping ‘observed’ Holton • 1970’s quantification Lilly • 1976 Schneider and and momentum budget by Lindzen -Cumulus Friction Swinbank • 1980’s NASA GLAS model- • 1980’s incorporation into Helfand NWP and climate models- • 1990’s pressure term- Miller and Palmer and Gregory McFarlane Atmospheric Gravity Waves Simple gravity wave model Topographic Gravity Waves and Drag • Flow over topography generates gravity (i.e. buoyancy) waves • <u’w’> is positive in example • Power spectrum of Earth’s topography α k-2 so there is a lot of subgrid orography • Subgrid orography generating unresolved gravity waves can transport momentum vertically • Let’s parameterize this mechanism! Begin with linear wave theory Simplest model for gravity waves: with Assume w’ α ei(kx+mz-σt) gives the dispersion relation or Linear theory (cont.) Sinusoidal topography ; set σ=0. Gives linear lower BC Small scale waves k>N/U0 decay Larger scale waves k<N/U0 propagate Semi-linear Parameterization Propagating solution with upward group velocity In the hydrostatic limit The surface drag can be related to the momentum transport δh=isentropic Momentum transport invariant by displacement Eliassen-Palm. Deposited when η=U linear theory is invalid (CL, breaking) z φ=phase Gravity Wave Drag Parameterization Convective or shear instabilty begins to dissipate wave- momentum flux no longer constant Waves propagate vertically, amplitude grows as r-1/2 (energy force cons.). -

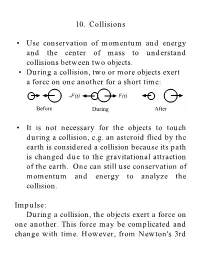

10. Collisions • Use Conservation of Momentum and Energy and The

10. Collisions • Use conservation of momentum and energy and the center of mass to understand collisions between two objects. • During a collision, two or more objects exert a force on one another for a short time: -F(t) F(t) Before During After • It is not necessary for the objects to touch during a collision, e.g. an asteroid flied by the earth is considered a collision because its path is changed due to the gravitational attraction of the earth. One can still use conservation of momentum and energy to analyze the collision. Impulse: During a collision, the objects exert a force on one another. This force may be complicated and change with time. However, from Newton's 3rd Law, the two objects must exert an equal and opposite force on one another. F(t) t ti tf Dt From Newton'sr 2nd Law: dp r = F (t) dt r r dp = F (t)dt r r r r tf p f - pi = Dp = ò F (t)dt ti The change in the momentum is defined as the impulse of the collision. • Impulse is a vector quantity. Impulse-Linear Momentum Theorem: In a collision, the impulse on an object is equal to the change in momentum: r r J = Dp Conservation of Linear Momentum: In a system of two or more particles that are colliding, the forces that these objects exert on one another are internal forces. These internal forces cannot change the momentum of the system. Only an external force can change the momentum. The linear momentum of a closed isolated system is conserved during a collision of objects within the system. -

The First Law of Thermodynamics for Closed Systems A) the Energy

Chapter 3: The First Law of Thermodynamics for Closed Systems a) The Energy Equation for Closed Systems We consider the First Law of Thermodynamics applied to stationary closed systems as a conservation of energy principle. Thus energy is transferred between the system and the surroundings in the form of heat and work, resulting in a change of internal energy of the system. Internal energy change can be considered as a measure of molecular activity associated with change of phase or temperature of the system and the energy equation is represented as follows: Heat (Q) Energy transferred across the boundary of a system in the form of heat always results from a difference in temperature between the system and its immediate surroundings. We will not consider the mode of heat transfer, whether by conduction, convection or radiation, thus the quantity of heat transferred during any process will either be specified or evaluated as the unknown of the energy equation. By convention, positive heat is that transferred from the surroundings to the system, resulting in an increase in internal energy of the system Work (W) In this course we consider three modes of work transfer across the boundary of a system, as shown in the following diagram: Source URL: http://www.ohio.edu/mechanical/thermo/Intro/Chapt.1_6/Chapter3a.html Saylor URL: http://www.saylor.org/me103#4.1 Attributed to: Israel Urieli www.saylor.org Page 1 of 7 In this course we are primarily concerned with Boundary Work due to compression or expansion of a system in a piston-cylinder device as shown above. -

Fluids – Lecture 7 Notes 1

Fluids – Lecture 7 Notes 1. Momentum Flow 2. Momentum Conservation Reading: Anderson 2.5 Momentum Flow Before we can apply the principle of momentum conservation to a fixed permeable control volume, we must first examine the effect of flow through its surface. When material flows through the surface, it carries not only mass, but momentum as well. The momentum flow can be described as −→ −→ momentum flow = (mass flow) × (momentum /mass) where the mass flow was defined earlier, and the momentum/mass is simply the velocity vector V~ . Therefore −→ momentum flow =m ˙ V~ = ρ V~ ·nˆ A V~ = ρVnA V~ where Vn = V~ ·nˆ as before. Note that while mass flow is a scalar, the momentum flow is a vector, and points in the same direction as V~ . The momentum flux vector is defined simply as the momentum flow per area. −→ momentum flux = ρVn V~ V n^ . mV . A m ρ Momentum Conservation Newton’s second law states that during a short time interval dt, the impulse of a force F~ applied to some affected mass, will produce a momentum change dP~a in that affected mass. When applied to a fixed control volume, this principle becomes F dP~ a = F~ (1) dt V . dP~ ˙ ˙ P(t) P + P~ − P~ = F~ (2) . out dt out in Pin 1 In the second equation (2), P~ is defined as the instantaneous momentum inside the control volume. P~ (t) ≡ ρ V~ dV ZZZ ˙ The P~ out is added because mass leaving the control volume carries away momentum provided ˙ by F~ , which P~ alone doesn’t account for. -

Law of Conversation of Energy

Law of Conservation of Mass: "In any kind of physical or chemical process, mass is neither created nor destroyed - the mass before the process equals the mass after the process." - the total mass of the system does not change, the total mass of the products of a chemical reaction is always the same as the total mass of the original materials. "Physics for scientists and engineers," 4th edition, Vol.1, Raymond A. Serway, Saunders College Publishing, 1996. Ex. 1) When wood burns, mass seems to disappear because some of the products of reaction are gases; if the mass of the original wood is added to the mass of the oxygen that combined with it and if the mass of the resulting ash is added to the mass o the gaseous products, the two sums will turn out exactly equal. 2) Iron increases in weight on rusting because it combines with gases from the air, and the increase in weight is exactly equal to the weight of gas consumed. Out of thousands of reactions that have been tested with accurate chemical balances, no deviation from the law has ever been found. Law of Conversation of Energy: The total energy of a closed system is constant. Matter is neither created nor destroyed – total mass of reactants equals total mass of products You can calculate the change of temp by simply understanding that energy and the mass is conserved - it means that we added the two heat quantities together we can calculate the change of temperature by using the law or measure change of temp and show the conservation of energy E1 + E2 = E3 -> E(universe) = E(System) + E(Surroundings) M1 + M2 = M3 Is T1 + T2 = unknown (No, no law of conservation of temperature, so we have to use the concept of conservation of energy) Total amount of thermal energy in beaker of water in absolute terms as opposed to differential terms (reference point is 0 degrees Kelvin) Knowns: M1, M2, T1, T2 (Kelvin) When add the two together, want to know what T3 and M3 are going to be. -

Aerodynamic Development of a IUPUI Formula SAE Specification Car with Computational Fluid Dynamics(CFD) Analysis

Aerodynamic development of a IUPUI Formula SAE specification car with Computational Fluid Dynamics(CFD) analysis Ponnappa Bheemaiah Meederira, Indiana- University Purdue- University. Indianapolis Aerodynamic development of a IUPUI Formula SAE specification car with Computational Fluid Dynamics(CFD) analysis A Directed Project Final Report Submitted to the Faculty Of Purdue School of Engineering and Technology Indianapolis By Ponnappa Bheemaiah Meederira, In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Technology Committee Member Approval Signature Date Peter Hylton, Chair Technology _______________________________________ ____________ Andrew Borme Technology _______________________________________ ____________ Ken Rennels Technology _______________________________________ ____________ Aerodynamic development of a IUPUI Formula SAE specification car with Computational 3 Fluid Dynamics(CFD) analysis Table of Contents 1. Abstract ..................................................................................................................................... 4 2. Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 5 3. Problem statement ..................................................................................................................... 7 4. Significance............................................................................................................................... 7 5. Literature review -

Leonhard Euler: His Life, the Man, and His Works∗

SIAM REVIEW c 2008 Walter Gautschi Vol. 50, No. 1, pp. 3–33 Leonhard Euler: His Life, the Man, and His Works∗ Walter Gautschi† Abstract. On the occasion of the 300th anniversary (on April 15, 2007) of Euler’s birth, an attempt is made to bring Euler’s genius to the attention of a broad segment of the educated public. The three stations of his life—Basel, St. Petersburg, andBerlin—are sketchedandthe principal works identified in more or less chronological order. To convey a flavor of his work andits impact on modernscience, a few of Euler’s memorable contributions are selected anddiscussedinmore detail. Remarks on Euler’s personality, intellect, andcraftsmanship roundout the presentation. Key words. LeonhardEuler, sketch of Euler’s life, works, andpersonality AMS subject classification. 01A50 DOI. 10.1137/070702710 Seh ich die Werke der Meister an, So sehe ich, was sie getan; Betracht ich meine Siebensachen, Seh ich, was ich h¨att sollen machen. –Goethe, Weimar 1814/1815 1. Introduction. It is a virtually impossible task to do justice, in a short span of time and space, to the great genius of Leonhard Euler. All we can do, in this lecture, is to bring across some glimpses of Euler’s incredibly voluminous and diverse work, which today fills 74 massive volumes of the Opera omnia (with two more to come). Nine additional volumes of correspondence are planned and have already appeared in part, and about seven volumes of notebooks and diaries still await editing! We begin in section 2 with a brief outline of Euler’s life, going through the three stations of his life: Basel, St. -

Chapter 6. Time Evolution in Quantum Mechanics

6. Time Evolution in Quantum Mechanics 6.1 Time-dependent Schrodinger¨ equation 6.1.1 Solutions to the Schr¨odinger equation 6.1.2 Unitary Evolution 6.2 Evolution of wave-packets 6.3 Evolution of operators and expectation values 6.3.1 Heisenberg Equation 6.3.2 Ehrenfest’s theorem 6.4 Fermi’s Golden Rule Until now we used quantum mechanics to predict properties of atoms and nuclei. Since we were interested mostly in the equilibrium states of nuclei and in their energies, we only needed to look at a time-independent description of quantum-mechanical systems. To describe dynamical processes, such as radiation decays, scattering and nuclear reactions, we need to study how quantum mechanical systems evolve in time. 6.1 Time-dependent Schro¨dinger equation When we first introduced quantum mechanics, we saw that the fourth postulate of QM states that: The evolution of a closed system is unitary (reversible). The evolution is given by the time-dependent Schrodinger¨ equation ∂ ψ iI | ) = ψ ∂t H| ) where is the Hamiltonian of the system (the energy operator) and I is the reduced Planck constant (I = h/H2π with h the Planck constant, allowing conversion from energy to frequency units). We will focus mainly on the Schr¨odinger equation to describe the evolution of a quantum-mechanical system. The statement that the evolution of a closed quantum system is unitary is however more general. It means that the state of a system at a later time t is given by ψ(t) = U(t) ψ(0) , where U(t) is a unitary operator. -

1. Define Open, Closed, Or Isolated Systems. If You Use an Open System As a Calorimeter, What Is the State Function You Can Calculate from the Temperature Change

CH301 Worksheet 13b Answer Key—Internal Energy Lecture 1. Define open, closed, or isolated systems. If you use an open system as a calorimeter, what is the state function you can calculate from the temperature change. If you use a closed system as a calorimeter, what is the state function you can calculate from the temperature? Answer: An open system can exchange both matter and energy with the surroundings. Δ H is measured when an open system is used as a calorimeter. A closed system has a fixed amount of matter, but it can exchange energy with the surroundings. Δ U is measured when a closed system is used as a calorimeter because there is no change in volume and thus no expansion work can be done. An isolated system has no contact with its surroundings. The universe is considered an isolated system but on a less profound scale, your thermos for keeping liquids hot approximates an isolated system. 2. Rank, from greatest to least, the types internal energy found in a chemical system: Answer: The energy that holds the nucleus together is much greater than the energy in chemical bonds (covalent, metallic, network, ionic) which is much greater than IMF (Hydrogen bonding, dipole, London) which depending on temperature are approximate in value to motional energy (vibrational, rotational, translational). 3. Internal energy is a state function. Work and heat (w and q) are not. Explain. Answer: A state function (like U, V, T, S, G) depends only on the current state of the system so if the system is changed from one state to another, the change in a state function is independent of the path.