Hommes Et Femmes De Science

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ley De Conservación De La Masa

CULTURA CIENTÍFICA para la Enseñanza Secundaria LEY DE CONSERVACIÓN DE LA MASA: DE LA ALQUIMIA A LA QUÍMICA MODERNA Antoine Laurent Lavoisier Este trabajo ha sido realizado en el marco de un proyecto de investigación docente conce- dido y financiado por el Vicerrectorado de Es- tudiantes y Acción Social y el Vicerrectorado de Investigación de la Universidad Católica de Valencia San Vicente Mártir. CULTURA CIENTÍFICA para la Enseñanza Secundaria Con este proyecto se pretende que los alum- nos de Enseñanza Secundaria Obligatoria (E.S.O.) adquieran una cultura científica y co- Edita: nozcan que la ciencia, la sociedad y la tecno- UNIVERSIDAD CATÓLICA DE VALENCIA logía no se pueden concebir aisladamente. Vicerrectorado de Estudiantes y Acción Social Alumnos y profesores hemos trabajado desde Vicerrectorado de Investigación una perspectiva multidisciplinar a través de Diseño y Maquetación: diferentes asignaturas y Grados Universitarios. Medianil Comunicación / medianil.com Autores: Stephany Cuellar Mosquera Sergio Gómez Molina Mariana Herrán Gonzalez Rocío Navarro Salazar Javier Pérez Murillo María Rojas Chacón José Urpin Rangel Asignatura: Fundamentos básicos de Química Profesor/a: Dra. Ángela Moreno Gálvez Grado: Nutrición Humana y Dietética Coordinadora: Dra. Gloria Castellano Estornell ÉRASE UNA VEZ 3 Descubrimiento de la Ley de conservación de la masa Antes de Lavoisier la Química como de los productos de una reacción ciencia apenas existía. Los cono- química debe ser igual al peso de cimientos que había eran vagos los reactantes, estableciendo que y estaban incluso en ocasiones “la materia ni se crea ni se destru- mezclados con conceptos cercanos ye en cualquier reacción química”, a lo mágico o lo esotérico, según y transformando así la química en la tradición alquímica provenien- ciencia con mayúsculas. -

LAVOISIER-The Crucial Year the Background and Origin of His First

LAVOISIER-THE CRUCIAL YEAR: The Background and Origin of His First Experiments on Combustion in z772 Antoine Laurent Lavoisier, 17 43-1794, a portrait by David (Photo Roger-Viollet) LA VOISIER -The Crucial Year The Background and Origin of His First Experiments on Combustion in 1772 /J_y llenr_y (Juerlac CORNELL UNIVERSITY CORNELL UNIVERSITY PRESS Ithaca, New York Open access edition funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities/Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. This work has been brought to publication with the assistance of a grant from the Ford Foundation. Copyright © 1961 by Cornell University First paperback printing 2019 The text of this book is li censed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommerciai-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. To use this book, or parts of this book, in any way not covered by the li cense, please contact Cornell University Press, Sage House, 512 East State Street, Ithaca, New York 14850. Visit our website at cornellpress.cornell.edu. Printed in the United States of America ISBN 978- 1-501 7-4663-5 (pbk.: alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-5017-4664-2 (pdf) ISBN 978-1-5017-4665-9 ( epub/mobi) Librarians: A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress TO Andrew Norman Meldrum (1876-1934) AND Helene Metzger (188g-1944) Acknowledgments MUCH of the research and much of the writing of a first draft of this book was completed while I was a mem ber of the Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton, in 1953-1955. -

Study Guide for Oxygen

STUDY GUIDE for OXYGEN By Carl Djerassi and Roald Hoffmann 1 The authors of the play “Oxygen” have distinguished careers as chemists. And they also have a commitment to reaching out to the general public, each in a distinct way, through essays, books, poems, novels, and plays. “Oxygen” is a play they have written together. The play has been performed in the USA, the UK and Germany, and broadcast over UK and German radio. It has also been published in book form in English, and in German translation, by Wiley-VCH. The play and the book serve as an excellent introduction to the culture and mores of science and scientists. The nature of discovery, the critical role of competition and priority, the joy and drama of discovery, the role of women in science – these are some of the issues that emerge in a lively, witty play. We believe “Oxygen,” whether in play or book form, can serve an important educational mission, stimulating interest and debate about the nature of science in young people. To help teachers at both the secondary and university level to present the play to young people, we have written this study guide. It first summarizes the play, and gives an extended description of the main characters (a selection of literature on the protagonists is also included). Then it sets some of the historical background for the events of the play, especially that of an erroneous but plausible chemical theory, phlogiston. And the way the discovery of oxygen played the critical role in the chemical revolution. We also include an essay by one of us on the way science has been portrayed in contemporary theatre. -

The Sublime in Art and Science

C. Djerassi & R. Hoffmann, “Oxygen (Oxygen-15 version) (Not to be copied without authors’ permission) OXYGEN (A play in 20 scenes) By Carl Djerassi and Roald Hoffmann Carl Djerassi Roald Hoffmann Department of Chemistry Department of Chemistry Stanford University Cornell University Stanford, CA 94305-5080 Ithaca, NY 14853-1301 Tel. 650-723-2783 Tel: 607-255-3419; Fax: 415-474-1868 Fax: 607-255-5707 e-mail: [email protected] e-mail: [email protected] URL: http://www.djerassi.com 1101 Green Street, Apt. 1501 San Francisco, CA 94109-2012 Tel: 415-474-1825; Fax: 415-474-1868 25 Warrington Crescent, Flat 3 London W9 1ED, United Kingdom Tel. 44-20-7289-3081; Fax:44-20-7289-5902 1 C. Djerassi & R. Hoffmann, “Oxygen (Oxygen-15 version) Authors’ Biographical Sketches Carl Djerassi Carl Djerassi, born in Vienna but educated in the US, is a writer and professor of chemistry at Stanford University. Author of over 1200 scientific publications and seven monographs, he is one of the few American scientists to have been awarded both the National Medal of Science (in 1973, for the first synthesis of a steroid oral contraceptive--”the Pill”) and the National Medal of Technology (in 1991, for promoting new approaches to insect control). A member of the US National Academy of Sciences and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences as well as many foreign academies, Djerassi has received 19 honorary doctorates together with numerous other honors, such as the first Wolf Prize in Chemistry, the first Award for the Industrial Application of Science from the National Academy of Sciences, and the American Chemical Society’s highest award, the Priestley Medal. -

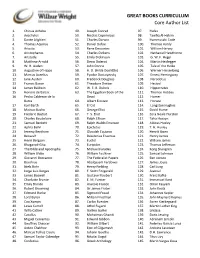

GREAT BOOKS CURRICULUM Core Author List

GREAT BOOKS CURRICULUM Core Author List 1. Chinua Achebe 49. Joseph Conrad 97. Hafez 2. Aeschylus 50. Nicolas Copernicus 98. Tawfiq Al-Hakim 3. Dante Alighieri 51. Charles Darwin 99. Hammurabi Code 4. Thomas Aquinas 52. Daniel Defoe 100. Thomas Hardy 5. Ariosto 53. Rene Descartes 101. William Harvey 6. Aristophanes 54. Charles Dickens 102. Nathaniel Hawthorne 7. Aristotle 55. Emily Dickinson 103. G. W. F. Hegel 8. Matthew Arnold 56. Denis Diderot 104. Martin Heidegger 9. W. H. Auden 57. John Donne 105. Tale of the Heike 10. Augustine of Hippo 58. H. D. (Hilda Doolittle) 106. Werner Heisenberg 11. Marcus Aurelius 59. Fyodor Dostoyevsky 107. Ernest Hemingway 12. Jane Austen 60. Frederick Douglass 108. Herodotus 13. Francis Bacon 61. Theodore Dreiser 109. Hesiod 14. James Baldwin 62. W. E. B. Dubois 110. Hippocrates 15. Honore de Balzac 63. The Egyptian Book of the 111. Thomas Hobbes 16. Pedro Calderon de la Dead 112. Homer Barca 64. Albert Einstein 113. Horace 17. Karl Barth 65. El Cid 114. Langston Hughes 18. Matsuo Basho 66. George Eliot 115. David Hume 19. Frederic Bastiat 67. T. S. Eliot 116. Zora Neale Hurston 20. Charles Baudelaire 68. Ralph Ellison 117. Taha Husayn 21. Samuel Beckett 69. Ralph Waldo Emerson 118. Aldous Huxley 22. Aphra Behn 70. Epictetus 119. T. H. Huxley 23. Jeremy Bentham 71. Olaudah Equiano 120. Henrik Ibsen 24. Beowulf 72. Desiderius Erasmus 121. Henry James 25. Henri Bergson 73. Euclid 122. William James 26. Bhagavad-Gita 74. Euripides 123. Thomas Jefferson 27. The Bible and Apocrypha 75. Michael Faraday 124. -

Biography: Antoine Laurent De Lavoisier Antoine Laurent De Lavoisier (1743 – 1794) Was a French Scientist Considered by Many to Be the Father of Modern Chemistry

Biography: Antoine Laurent de Lavoisier Antoine Laurent de Lavoisier (1743 – 1794) was a French scientist considered by many to be the father of modern chemistry. His most im- portant experiments investigated the nature of ignition and combustion. While not having discovered any new substances in his lifetime, he im- proved laboratory methods and devised the system of chemical terminol- ogy which is, to a great extent, still used today. He was instrumental in the overthrow of phlogiston theory. Moreover, he proved the law of con- servation of mass and discovered that hydrogen, in combination with ox- ygen, produces water. His work was characterized by organizational skills, abundance of good ideas, universality, and modernism. As a result of his accomplishments, his name appears among the 72 names at the Eiffel Tower. Lavoisier was born in Paris on August 26, 1743. mineralogy. It was shortly after his graduation, on He was born to an affluent bank-clerk family. At August 11, 1764, that he began his apprenticeship the age of five, he inherited possessions left to him in the Parisian Parliament (Parlement de Paris). after his mother’s death. From a young age, he was He was open-minded and curious about every- interested in nature and he often carried out bar- thing that surrounded him. Not giving up on his ometrical and meteorological observations. interests, he devoted himself to geology, physics, In 1754, Antoine started attending Collège des and chemistry, which resulted in his first pub- Quatre Nations (Collège Mazarin), which was lished book in chemistry in 1764. known for its advanced teaching and focus on Ex- In 1767, he obtained a job working as a geolo- act and Natural Sciences. -

The Scientific Revolution

Causes of the Scientific Revolution The development of new technology and scientific theories became the foundation of the Scientific Revolution. Section 1 Causes of the Scientific Revolution (cont.) • By mastering Greek, European humanists were able to read newly discovered works by the philosophers Ptolemy, Archimedes, and Plato. • New technology such as the telescope and microscope enabled individuals to make new scientific discoveries. • The printing press helped spread new ideas quickly and easily. Section 1 Figure 1 Causes of the Scientific Revolution (cont.) • Advances in mathematics made calculations easier and played a key role in scientific achievements. • Advances in algebra, trigonometry, and geometry allowed scientists to demonstrate proofs for their theories. Section 1 Figure 1 Scientific Breakthroughs Scientific discoveries expanded knowledge about the universe and the human body. Section 1 Scientific Breakthroughs (cont.) • Astronomers of the Middle Ages constructed a model of the universe called the Ptolemaic system after the astronomer Ptolemy. • The Ptolemaic system is geocentric because it places Earth at the center of the universe. • During the Scientific Revolution, Nicolaus Copernicus offered the heliocentric theory, which put the sun at the center of the universe. Section 1 Scientific Breakthroughs (cont.) • Johannes Kepler added to this theory by confirming the central position of the sun and adding information about the elliptical orbits of the planets. • Galileo Galilei used a telescope to observe mountains on the moon, sun spots, and new moons in the heavens. His ideas were revolutionary and brought him into conflict with the Catholic Church. Section 1 Figure 2 Scientific Breakthroughs (cont.) • Isaac Newton explained how the planets continually orbit the sun. -

Sensible Instruments Conference Draft 1

Sensible Instruments: Remaking Society through the Body in the French Enlightenment Carolyn Purnell Introduction: The Philosopher-Instrument and the Culture of Sensibility 3 Part One: Sensibility Chapter One. 20 The Troubling Essence of Feeling: The Stable Characteristics of Sensibility A Brief History of Sensible Medicine A Brief History of Sensationalist Philosophy Establishing the Stable Characteristics 1) Sensibility Was a Faculty Involving a Perceptual Act 2) Sensibility Linked the Physical, Mental, and Moral 3) Sensibility Was Manipulable 4) Sensibility Functioned Economically Conclusion Chapter Two. 57 Simple Pleasures: The Ocular Harpsichord and the Stabilization of the Discourse of Sensibility Louis-Bertrand Castel and the Theory of Color-Music The Relationship of the Harpsichord to the Discourse of Sensibility 1) The Simple Agreement Model of Pleasure 2) The Je ne sais quoi 3) Education and Habit in Castel’s System 4) Fatigue and Economic Functioning Conclusion Chapter Three. 95 Castel Redux: Instrumentalizing the Sensible The Material History of the Harpsichord and its Seven Pleasures Resituating the Ocular Harpsichord within the Discourse of Sensibility Conclusion Part Two: Instruments Chapter Four. 130 All that is Pleasant and Useful: Regimens of Talent and Political Economic Improvement Connections Between Animal Economy and Political Economy Antoine Le Camus: Systematizing Non-Natural Regimens to Create Hommes d’Esprit The Maison d’Education of Jean Verdier Valentin Haüy and the Institut des jeunes avegules Conclusion Chapter Five. 179 Charged with Feeling: Medical Electricity and the Social Incorporation of the Useful Individual Electricity and Sensibility: Applications and Connections 1 Paralysis and Electricity The First Wave: The Académie royale des Sciences and the Hôtel des Invalides The Second Wave: Mauduyt’s Trials for the Sociéte royale de médecine Conclusion: Patients’ and Doctors’ Perspectives on the Treatment’s Efficacy Chapter Six. -

OS AMORES DE MARIE ANNE PAULZE. Parte I: Os Amores Desinteresados

OS AMORES DE MARIE ANNE PAULZE. Parte I: Os Amores Desinteresados Ana M. González Noya Xoana Pintos Barral Manolo R. Bermejo Dpto. de Química Inorgánica Universidade de Santiago de Compostela 1. Introdución A experiencia vital de Marie Anne Paulze foi completa ao longo da súa moi lonxeva vida. Cando exploramos a súa existencia centrámonos tan só, ou case sempre, en que foi a muller do gran Lavoisier, o xenio ou “Pai da Química” moderna e chamámola, a ela, como a “Nai da Química”. De cote esquecemos que a historia de Marie, ao lado de Antoine, foi moi curta: tan só vinte e tres anos; pero para Marie quedaban, aínda, unha vida plena de máis de 40 anos, ata alcanzar a idade de setenta e oito anos. Para comprender mellor a biografía e a obra de Marie Anne Paulze Lavoisier cómpre estudar e entender a súa traxectoria. Nesta comunicación centrarémonos en analizar algúns dos moitos amores desinteresados que tivo Marie Anne ao longo da súa vida, deixaremos de lado a súa vida científica e a de salonniere, que xa foi considerada noutras comunicacións presentadas por nós en ENCIGA. Contaremos nesta comunicación como se xeraron os seus amores familiares, e como estes desencadearon o seu amor cara a cultura no seu máis amplo espectro. Este amor pola cultura haa poñer en contacto coa Ciencia e con quen será o seu grande amor: Antoine Lavoisier. Mais tamén cos seus grandes desamores. A obra de Marie Anne Paulze Lavoisier, e tamén a súa vida, merecen ser coñecidas por todo o mundo, pero particularmente polas mocidades de hoxe, como un exemplo da historia da ciencia. -

EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY THEORIES of the NATURE of HEAT. the U

This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received ^ 5—13,888 MORRIS, Jr., Robert James, 1932— EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY THEORIES OF THE NATURE OF HEAT. The University of Oklahoma, Ph.D., 1965 History, modern University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan Copyright By Robert James Morris, Jr. 1966 THE UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA. GRADUATE COLLEGE EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY THEORIES OF THE NATURE OF HEAT A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY BY ROBERT JAMES MORRIS, JR. Norman, Oklahoma 1965 EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY THEORIES OF THE NATURE OF HEAT APPROVED BY [2- 0 C ^ • \CwÆ-UC^C>._____ DISSERTATION COMMITTEE ACKNOWLEDGMENTS To Duane H. D. Roller, McCasland Professor of the History of Science, whose provocative and intriguing lectures first enticed me into the study of the history of science, and to Thomas M. Smith, Associate Professor of the History of Science, for their suggestions and criticisms concerning this dissertation, for their encouragement, confidence, and assistance freely given throughout my years of graduate study, and for their advice and friendship which made these years enjoyable as well as profitableo To Professor Charles J. Mankin, Director of the Department of Geology, Leroy E. Page, Assistant Professor of the History of Science, and Robert L- Reigle, Instructor of History, for reading and criticizing this dissertation. To Marcia M. Goodman, Librarian of the History of Science Collections, for her aid in obtaining sources needed for this study and for her personal interest, encouragement and friendship. To George P. Burris and Dwayne R. Mason for their selfless, untiring help in the preparation of the manuscript. -

Encyclopedia Britannica's Great Authors List

THE GREAT BOOKS PROGRAM's GREAT BOOKS AUTHORS LIST Based upon the Encyclopedia Britannica's list of Great Books of the Western World A B C D E F Aeschylus Francis Bacon Cao Xueqin Dante Eddington Michael Faraday Isabel Allende* Balzac John Calvin Charles Darwin Albert Einstein William Faulkner Jorge Amado Barth Joseph Campbell* Richard Dawkins* El Cid The Federalist Papers Maya Angelou* Matsuo Basho Albert Camus* Daniel Defoe George Eliot Henry Fielding St. Anselm* Charles Baudelaire Willa Cather Rene Descartes T.S. Eliot F. Scott Fitzgerald Thomas Aquinas Jeremy Bentham Miguel Cervantes Dewey Ralph Ellison Gustave Flaubert Archimedes Beowulf Geoffrey Chaucer Junot Díaz* Ralph Waldo Emerson E. M. Forster Matthew Arnold Samuel Beckett Anton Chekhov Charles Dickens Engles Anatole France Machado de Assisi Thomas Berger Kate Chopin* Emily Dickinson Epic of Son Jara James Frazer Aristophanes Henri Bergson Cicero Denis Diderot Epictetus Sigmund Freud Aristotle Berkeley Sandra Cisneros* Annie Dillard* Desiderius Erasmus Milton Friedman* Margaret Atwood* Bhagavad Gita J.M. Le Clezio* Dobzhansky Euclid St. Augustine Bible Samuel Coleridge John Donne Euripides W. H. Auden William Blake Confucius Fyodor Dostoyevsky Marcus Aurelius Giovanni Boccaccio Joseph Conrad Frederick Douglass Jane Austen Boethius Nicolas Copernicus Theodore Dreiser Niels Bohr Pierre Corneille John Dryden Jorge Borges W.E.B. Dubois James Boswell Emile Durkheim* TC Boyle* Simone de Beauvoir* Berthold Brecht Edmund Burke Robert Browning * Denotes an author added by a vote of the ACC Great Books Faculty THE GREAT BOOKS PROGRAM's GREAT BOOKS AUTHORS LIST Based upon the Encyclopedia Britannica's list of Great Books of the Western World G H, I J K L M Galen Henrik Ibsen Henry James Franz Kafka Antoine Lavoisier Thomas Macauley Galileo Galilei William James Immanuel Kant D.H. -

Conservation of Mass

Conservation of Mass The Law of Conservation of Mass dates from Antoine Lavoisier's 1789 discovery that mass is neither created nor destroyed in chemical reactions. In other words, the mass of any one element at the beginning of a reaction will equal the mass of that element at the end of the reaction. If we account for all reactants and products in a chemical reaction, the total mass will be the same at any point in time in any closed system. The formulation of this law near the end of the eighteenth century marked the beginning of modern chemistry. By that time many elements had been isolated and identified, most notably oxygen, nitrogen, and hydrogen. It was also known that, when a pure metal was heated in air, it became what was then called a calx (which we now call an oxide) and that this change was accompanied by an increase in mass. The reverse of this reaction was also known: Many calxes on heating lost mass and returned to pure metals. Many imaginative explanations of these mass changes were proposed. Antoine Lavoisier (1743-1794), a French nobleman later guillotined in the revolution, was an amateur chemist with a remarkably analytical mind. He considered the properties of metals and then carried out a series of experiments designed to allow him to measure not just the mass of the metal and the calx but also the mass of the air surrounding the reaction. His results showed that the mass gained by the metal in forming the calx was equal to the mass lost by the surrounding air.