The Scientific Revolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 21 Lesson Reviews

Chapter 21 Lesson Reviews Question Answer 1. Write a paragraph explaining how the In the scientific method, the scientist observes scientific method exemplified the new events, creates a hypothesis, and then tests it. emphasis on reason. The scientist uses the same reasonable process each time. 3. What developments were the foundation of The new reliance by scientists on direct the Scientific Revolution? observation and experiment marked a complete change from the reliance on ancient authorities for scientific knowledge. 4. What role did scientific breakthroughs play Students' answers should note that during the Scientific Revolution? breakthroughs, like Copernicus's new concept of the universe, cast doubt on long-held ideas. 5. What obstacles did participants in the Participants in the Scientific Revolution faced the Scientific Revolution face? challenge that the old, long-held ideas were still very powerful, especially in the view of the Church. 6. How did the Scientific Revolution change Scientific discoveries led Descartes to the belief people's worldview? that reason is the chief source of knowledge. Bacon used inductive reasoning to establish the scientific method. 1. Write a paragraph explaining what Montesquieu used England as an example of a Montesquieu meant by the phrase separation government with separation of powers. This of powers and where he saw this principle system provides the greatest freedom and applied. security for the state. 3. How did Enlightenment thinkers use the They tried to use reason to find the natural law ideas of the Scientific Revolution? that governed human behavior. They also questioned the ideas of ancient authorities and the Church. -

Enlightened Despotism

ENLIGHTENED DESPOTISM FRITZ HARTUNG 2s 6d PUBLISHED FOR THE HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION BY ROUTLEDGE AND KEGAN PAUL [G. 36] ENLIGHTENED DESPOTISM THIS PAMPHLET IS GENERAL SERIES NUMBER 36 First published 1957 Reprinted 1963 FRITZ HARTUNG Copyright by the Historical Association Printed in Great Britain by Cox and Wyman Ltd., London, Reading and Fakenham Non-members may obtain copies 2s. 6d. each (post free], and members may obtain extra copies at is. 6d. each (postfree) from the Hon. Secretary of the Associa- tion, 59A, Kennington Park Road, London, S.E.li The publication of a pamphlet by the Historical Association does not necessarily imply the Association s official approbation of the opinions expressed therein Obtainable only through booksellers or from the offices of the Association 1957 Reprinted 1963 ENLIGHTENED DESPOTISM SAINT AUGUSTINE once said: " If no one enquires of me, I know; if I want to explain to an enquirer, I do not know ". That is also the position of historians who have to deal with " En- lightened Absolutism ", or (as it is usually called in English) " Enlightened Despotism". When, some forty years ago, lecturing on modern constitutional history, I had for the first PREFACE time to deal with the subject in detail, it was still possible to treat it as a clearly defined and unambiguous notion. It was, It is a privilege for the Historical Association to have the opportunity of publishing this pamphlet by Professor Fritz Hartung, in an English version prepared by Miss in fact, the only stage which in the controversy about the H. Otto and revised by the present writer. -

Enlightened Monarchy” in Practice

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Helsingin yliopiston digitaalinen arkisto “Enlightened Monarchy” in Practice. Reforms, Ceremonies, Self-Fashioning and the Entanglement of Ideals and Values in Late Eighteenth-Century Sweden Henrika Tandefelt This article sets out to study the entanglement of different political, ideological and moral ideals and traditions in the Kingship of Gustav III, King of Sweden 1772–1792. Political thinking and practice in Eighteenth-Century Europe offered many elements and examples that different monarchs could apply in their own particular circumstances. Gustav III was one of the European Kings that openly supported the French enlightened thinkers fashioning himself as a Reformer-King. He was also very influenced by the French culture over all, and the culture of the traditional royal court in particular. In addition the Swedish political history with a fifty-year period of decreased royal power before the coup d’état of Gustav III in 1772 influenced how the European trends and traditions were put into practice. The article pursues to understand the way different elements were bound up together and put to action by the King in his coup d’état 1772, his law reforms in the 1770s and in the establishment of a court of appeal in the town Vasa in Ostrobothnia in 1776 and the ceremonial, pictorial and architectural projects linked to this. In this article I examine what has been called the enlightened absolutism of the Swedish king Gustav III (1746–1792) during his reign of 1772–1792. Gustav III’s reign began with a royal coup d’état in August 1772 and ended with the king being murdered during a masquerade ball at the Royal Opera in Stockholm in March 1792. -

Ley De Conservación De La Masa

CULTURA CIENTÍFICA para la Enseñanza Secundaria LEY DE CONSERVACIÓN DE LA MASA: DE LA ALQUIMIA A LA QUÍMICA MODERNA Antoine Laurent Lavoisier Este trabajo ha sido realizado en el marco de un proyecto de investigación docente conce- dido y financiado por el Vicerrectorado de Es- tudiantes y Acción Social y el Vicerrectorado de Investigación de la Universidad Católica de Valencia San Vicente Mártir. CULTURA CIENTÍFICA para la Enseñanza Secundaria Con este proyecto se pretende que los alum- nos de Enseñanza Secundaria Obligatoria (E.S.O.) adquieran una cultura científica y co- Edita: nozcan que la ciencia, la sociedad y la tecno- UNIVERSIDAD CATÓLICA DE VALENCIA logía no se pueden concebir aisladamente. Vicerrectorado de Estudiantes y Acción Social Alumnos y profesores hemos trabajado desde Vicerrectorado de Investigación una perspectiva multidisciplinar a través de Diseño y Maquetación: diferentes asignaturas y Grados Universitarios. Medianil Comunicación / medianil.com Autores: Stephany Cuellar Mosquera Sergio Gómez Molina Mariana Herrán Gonzalez Rocío Navarro Salazar Javier Pérez Murillo María Rojas Chacón José Urpin Rangel Asignatura: Fundamentos básicos de Química Profesor/a: Dra. Ángela Moreno Gálvez Grado: Nutrición Humana y Dietética Coordinadora: Dra. Gloria Castellano Estornell ÉRASE UNA VEZ 3 Descubrimiento de la Ley de conservación de la masa Antes de Lavoisier la Química como de los productos de una reacción ciencia apenas existía. Los cono- química debe ser igual al peso de cimientos que había eran vagos los reactantes, estableciendo que y estaban incluso en ocasiones “la materia ni se crea ni se destru- mezclados con conceptos cercanos ye en cualquier reacción química”, a lo mágico o lo esotérico, según y transformando así la química en la tradición alquímica provenien- ciencia con mayúsculas. -

Course Name: HIST 4 Title: History of Western Civilization Units

Course Name: HIST 4 Title: History of Western Civilization Units: 3 Course Description: This course is a survey of western civilization from the Renaissance to the present, emphasizing the interplay of social, political, economic, cultural, and intellectual forces in creating and shaping the modern world. The focus is on the process of modernization, stressing the secularization of western society and examining how war and revolution have served to create our world. Course Objectives: Upon completion of this course, the student will be able to: identify and correctly use basic historical terminology distinguish between primary and secondary sources as historical evidence compare and evaluate various interpretations used by historians to explain the development of western civilization since the Renaissance evaluate multiple causes and analyze why a historical event happened identify the major eras and relevant geography of western civilization since the Renaissance evaluate major economic, social, political, and cultural developments in western civilization since the Renaissance evaluate the experiences, conflicts, and connections of diverse groups of people in western civilization since the Renaissance draw historical generalizations about western civilization since the Renaissance based on understanding of the historical evidence describe and evaluate the major movements and historical forces that have contributed to the development of western civilization. Course Content: 4 hours: Introduction to the Study of Western Civilization, Historiography; Age of Transition: The Early Modern Period. 3 hours: The Nature and Structure of Medieval Society; those who work, those who pray, those who fight, the Great Chain of Being, manorialism; Decline of the Medieval Synthesis; The Renaissance and the Question of Modernity: humanism, individualism, secular spirit, Petrarch, Bruni, Pico, Castiglione, Machiavelli, etc., literature, art, and politics. -

LAVOISIER-The Crucial Year the Background and Origin of His First

LAVOISIER-THE CRUCIAL YEAR: The Background and Origin of His First Experiments on Combustion in z772 Antoine Laurent Lavoisier, 17 43-1794, a portrait by David (Photo Roger-Viollet) LA VOISIER -The Crucial Year The Background and Origin of His First Experiments on Combustion in 1772 /J_y llenr_y (Juerlac CORNELL UNIVERSITY CORNELL UNIVERSITY PRESS Ithaca, New York Open access edition funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities/Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. This work has been brought to publication with the assistance of a grant from the Ford Foundation. Copyright © 1961 by Cornell University First paperback printing 2019 The text of this book is li censed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommerciai-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. To use this book, or parts of this book, in any way not covered by the li cense, please contact Cornell University Press, Sage House, 512 East State Street, Ithaca, New York 14850. Visit our website at cornellpress.cornell.edu. Printed in the United States of America ISBN 978- 1-501 7-4663-5 (pbk.: alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-5017-4664-2 (pdf) ISBN 978-1-5017-4665-9 ( epub/mobi) Librarians: A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress TO Andrew Norman Meldrum (1876-1934) AND Helene Metzger (188g-1944) Acknowledgments MUCH of the research and much of the writing of a first draft of this book was completed while I was a mem ber of the Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton, in 1953-1955. -

Study Guide for Oxygen

STUDY GUIDE for OXYGEN By Carl Djerassi and Roald Hoffmann 1 The authors of the play “Oxygen” have distinguished careers as chemists. And they also have a commitment to reaching out to the general public, each in a distinct way, through essays, books, poems, novels, and plays. “Oxygen” is a play they have written together. The play has been performed in the USA, the UK and Germany, and broadcast over UK and German radio. It has also been published in book form in English, and in German translation, by Wiley-VCH. The play and the book serve as an excellent introduction to the culture and mores of science and scientists. The nature of discovery, the critical role of competition and priority, the joy and drama of discovery, the role of women in science – these are some of the issues that emerge in a lively, witty play. We believe “Oxygen,” whether in play or book form, can serve an important educational mission, stimulating interest and debate about the nature of science in young people. To help teachers at both the secondary and university level to present the play to young people, we have written this study guide. It first summarizes the play, and gives an extended description of the main characters (a selection of literature on the protagonists is also included). Then it sets some of the historical background for the events of the play, especially that of an erroneous but plausible chemical theory, phlogiston. And the way the discovery of oxygen played the critical role in the chemical revolution. We also include an essay by one of us on the way science has been portrayed in contemporary theatre. -

Culture and Politics 1700-1815 Handbook 2010-11

HI2108 Culture and Politics in Europe 1700-1815 Course co-ordinator Dr. Joseph Clarke (Dept. of History) Contact details [email protected] Room 3153 Teaching Staff Dr. Joseph Clarke, Dr. Linda Kiernan Duration One semester (Michaelmas term) Assessment Essays, one 2 hour exam. Weighting 10 ECTS Lecture Times Thursday, 11.00 – 12.00, room 3074 Friday, 12.00 – 1.00, Edmund Burke Theatre Course Description: The ‘long eighteenth-century’ that led from Louis XIV to Napoleon was an age of unprecedented cultural and political change. In order to understand the nature and extent of this change, this course charts the emergence of new ways of thinking about science, society and the self during the Enlightenment and explores how these ideas contributed to reshaping the state during the Revolutionary crisis that convulsed Europe from 1789 on. By examining the evolution of attitudes towards gender, death and family life, the course also explores how perceptions of private life and popular culture changed over the 18th century. 1 Learning Outcomes: On successful completion of this module students should be able to: • Demonstrate an informed understanding of the main themes and developments in the political and cultural history of Europe from 1700 to 1815. • Engage critically with the scholarly literature on this subject. • Evaluate a range of methodological and theoretical approaches to the study of 18th century political and cultural history. • Identify and interpret a range of relevant primary sources. • Communicate their conclusions clearly in both written and verbal contexts. Course Structure: Week 1 1 Introduction: What is Cultural History? 2 The Culture of the Court and the Culture of Custom Week 2 3 From the Republic of Letters to the Public Sphere 4 ‘What is Enlightenment?’ Week 3 5 Enlightenment in action: the Encyclopédie. -

The Sublime in Art and Science

C. Djerassi & R. Hoffmann, “Oxygen (Oxygen-15 version) (Not to be copied without authors’ permission) OXYGEN (A play in 20 scenes) By Carl Djerassi and Roald Hoffmann Carl Djerassi Roald Hoffmann Department of Chemistry Department of Chemistry Stanford University Cornell University Stanford, CA 94305-5080 Ithaca, NY 14853-1301 Tel. 650-723-2783 Tel: 607-255-3419; Fax: 415-474-1868 Fax: 607-255-5707 e-mail: [email protected] e-mail: [email protected] URL: http://www.djerassi.com 1101 Green Street, Apt. 1501 San Francisco, CA 94109-2012 Tel: 415-474-1825; Fax: 415-474-1868 25 Warrington Crescent, Flat 3 London W9 1ED, United Kingdom Tel. 44-20-7289-3081; Fax:44-20-7289-5902 1 C. Djerassi & R. Hoffmann, “Oxygen (Oxygen-15 version) Authors’ Biographical Sketches Carl Djerassi Carl Djerassi, born in Vienna but educated in the US, is a writer and professor of chemistry at Stanford University. Author of over 1200 scientific publications and seven monographs, he is one of the few American scientists to have been awarded both the National Medal of Science (in 1973, for the first synthesis of a steroid oral contraceptive--”the Pill”) and the National Medal of Technology (in 1991, for promoting new approaches to insect control). A member of the US National Academy of Sciences and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences as well as many foreign academies, Djerassi has received 19 honorary doctorates together with numerous other honors, such as the first Wolf Prize in Chemistry, the first Award for the Industrial Application of Science from the National Academy of Sciences, and the American Chemical Society’s highest award, the Priestley Medal. -

Hommes Et Femmes De Science

EXERCICE : HOMMES ET FEMMES DE SCIENCE PRESENTATION Objectifs : découvrir l’essor des sciences, ses acteurs, ses facteurs, ses méthodes. S’exercer à l’expression orale. Outils proposés : un corpus de fiches complémentaires présente des savant-e-s du 18ème siècle, leur fonctionnement en réseau, leurs origines sociales, le rôle qu’y tiennent deux femmes, les limites de la place qui leur est reconnue. On pourra les utiliser dans un travail de groupe, avec mise en commun et construction d’une trace écrite. Par exemple un schéma heuristique à compléter dans une phase d’écoute active, comme exercice de prise de notes… Compétences mises en œuvre : prélever et hiérarchiser des informations ; présenter à l’oral un exposé construit en utilisant le vocabulaire spécifique ; prendre part à une production collective. Intérêt des exemples proposés : focaliser sur ce moment de l’histoire des sciences permet de présenter un réseau de scientifiques, et de dépasser la figure du « héros des sciences » tel Newton. Le réseau de savants présenté ici comprend des femmes. Deux exemples de femmes de science : Emilie du Chatelet et Marie Anne Lavoisier sont deux rares exemples de femmes de science relativement bien documentées. Emilie du Chatelet est célèbre mais a souvent été présentée sous un jour qui n’échappe pas aux stéréotypes de genre : traductrice de Newton, passeuse, vulgarisatrice, frivole maîtresse de Voltaire. Or, il faut insister sur sa carrière propre et indépendante de scientifique. Après une jeunesse à la cour, et dans le monde, elle s’émancipe de Voltaire et se spécialise dans le perfectionnement des thèses de Newton. Elle fait la synthèse avec les intuitions de Leibnitz, qu’elle démontre, participe à des polémiques entre savants, réfute le secrétaire perpétuel de l’Académie des sciences dans la « querelle des forces vives ». -

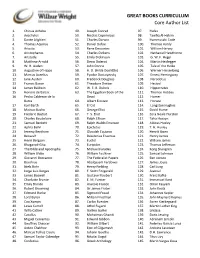

GREAT BOOKS CURRICULUM Core Author List

GREAT BOOKS CURRICULUM Core Author List 1. Chinua Achebe 49. Joseph Conrad 97. Hafez 2. Aeschylus 50. Nicolas Copernicus 98. Tawfiq Al-Hakim 3. Dante Alighieri 51. Charles Darwin 99. Hammurabi Code 4. Thomas Aquinas 52. Daniel Defoe 100. Thomas Hardy 5. Ariosto 53. Rene Descartes 101. William Harvey 6. Aristophanes 54. Charles Dickens 102. Nathaniel Hawthorne 7. Aristotle 55. Emily Dickinson 103. G. W. F. Hegel 8. Matthew Arnold 56. Denis Diderot 104. Martin Heidegger 9. W. H. Auden 57. John Donne 105. Tale of the Heike 10. Augustine of Hippo 58. H. D. (Hilda Doolittle) 106. Werner Heisenberg 11. Marcus Aurelius 59. Fyodor Dostoyevsky 107. Ernest Hemingway 12. Jane Austen 60. Frederick Douglass 108. Herodotus 13. Francis Bacon 61. Theodore Dreiser 109. Hesiod 14. James Baldwin 62. W. E. B. Dubois 110. Hippocrates 15. Honore de Balzac 63. The Egyptian Book of the 111. Thomas Hobbes 16. Pedro Calderon de la Dead 112. Homer Barca 64. Albert Einstein 113. Horace 17. Karl Barth 65. El Cid 114. Langston Hughes 18. Matsuo Basho 66. George Eliot 115. David Hume 19. Frederic Bastiat 67. T. S. Eliot 116. Zora Neale Hurston 20. Charles Baudelaire 68. Ralph Ellison 117. Taha Husayn 21. Samuel Beckett 69. Ralph Waldo Emerson 118. Aldous Huxley 22. Aphra Behn 70. Epictetus 119. T. H. Huxley 23. Jeremy Bentham 71. Olaudah Equiano 120. Henrik Ibsen 24. Beowulf 72. Desiderius Erasmus 121. Henry James 25. Henri Bergson 73. Euclid 122. William James 26. Bhagavad-Gita 74. Euripides 123. Thomas Jefferson 27. The Bible and Apocrypha 75. Michael Faraday 124. -

Biography: Antoine Laurent De Lavoisier Antoine Laurent De Lavoisier (1743 – 1794) Was a French Scientist Considered by Many to Be the Father of Modern Chemistry

Biography: Antoine Laurent de Lavoisier Antoine Laurent de Lavoisier (1743 – 1794) was a French scientist considered by many to be the father of modern chemistry. His most im- portant experiments investigated the nature of ignition and combustion. While not having discovered any new substances in his lifetime, he im- proved laboratory methods and devised the system of chemical terminol- ogy which is, to a great extent, still used today. He was instrumental in the overthrow of phlogiston theory. Moreover, he proved the law of con- servation of mass and discovered that hydrogen, in combination with ox- ygen, produces water. His work was characterized by organizational skills, abundance of good ideas, universality, and modernism. As a result of his accomplishments, his name appears among the 72 names at the Eiffel Tower. Lavoisier was born in Paris on August 26, 1743. mineralogy. It was shortly after his graduation, on He was born to an affluent bank-clerk family. At August 11, 1764, that he began his apprenticeship the age of five, he inherited possessions left to him in the Parisian Parliament (Parlement de Paris). after his mother’s death. From a young age, he was He was open-minded and curious about every- interested in nature and he often carried out bar- thing that surrounded him. Not giving up on his ometrical and meteorological observations. interests, he devoted himself to geology, physics, In 1754, Antoine started attending Collège des and chemistry, which resulted in his first pub- Quatre Nations (Collège Mazarin), which was lished book in chemistry in 1764. known for its advanced teaching and focus on Ex- In 1767, he obtained a job working as a geolo- act and Natural Sciences.