The State of Framing Research: a Call for New Directions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Social Media and the Spiral of Silence: the Case of Kuwaiti Female Students’ Political Discourse on Twitter

Journal of International Women's Studies Volume 16 | Issue 3 Article 4 Jul-2015 Social Media and the Spiral of Silence: The aC se of Kuwaiti Female Students Political Discourse on Twitter Ali A. Dashti Hamed H. Al-Abdullah Hasan A. Johar Follow this and additional works at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws Part of the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Dashti, Ali A.; Al-Abdullah, Hamed H.; and Johar, Hasan A. (2015). Social Media and the Spiral of Silence: The asC e of Kuwaiti Female Students Political Discourse on Twitter. Journal of International Women's Studies, 16(3), 42-53. Available at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol16/iss3/4 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. This journal and its contents may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. ©2015 Journal of International Women’s Studies. Social Media and the Spiral of Silence: The Case of Kuwaiti Female Students’ Political Discourse on Twitter By Ali A. Dashti1, Hamed H Al-Abdullah2 and Hasan A Johar3 Abstract The theory of the Spiral of Silence (Noelle-Neumann, 1984), explained why the view of a minority is not presented when the majority view dominates the public sphere. For years the theory of the spiral of silence was used to describe the isolation of minority opinions when seeking help from traditional media, which play a significant role in increasing the isolation. -

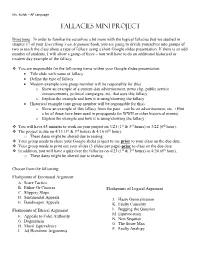

Fallacies Mini Project

Ms. Kizlyk – AP Language Fallacies Mini Project Directions: In order to familiarize ourselves a bit more with the logical fallacies that we studied in chapter 17 of your Everything’s an Argument book, you are going to divide yourselves into groups of two to teach the class about a type of fallacy using a short Google slides presentation. If there is an odd number of students, I will allow a group of three – you will have to do an additional historical or modern day example of the fallacy. You are responsible for the following items within your Google slides presentation: Title slide with name of fallacy Define the type of fallacy Modern example (one group member will be responsible for this) o Show an example of a current-day advertisement, news clip, public service announcements, political campaigns, etc. that uses this fallacy o Explain the example and how it is using/showing the fallacy Historical example (one group member will be responsible for this) o Show an example of this fallacy from the past – can be an advertisement, etc. (Hint – a lot of these have been used in propaganda for WWII or other historical events). o Explain the example and how it is using/showing the fallacy You will have 45 minutes to work on your project on 3/21 (1st & 3rd hours) or 3/22 (6th hour). The project is due on 4/13 (1st & 3rd hours) & 4/16 (6th hour). o These dates might be altered due to testing. Your group needs to share your Google slides project to me prior to your class on the due date. -

Social Norms and Social Influence Mcdonald and Crandall 149

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect Social norms and social influence Rachel I McDonald and Christian S Crandall Psychology has a long history of demonstrating the power and and their imitation is not enough to implicate social reach of social norms; they can hardly be overestimated. To norms. Imitation is common enough in many forms of demonstrate their enduring influence on a broad range of social life — what creates the foundation for culture and society phenomena, we describe two fields where research continues is not the imitation, but the expectation of others for when to highlight the power of social norms: prejudice and energy imitation is appropriate, and when it is not. use. The prejudices that people report map almost perfectly onto what is socially appropriate, likewise, people adjust their A social norm is an expectation about appropriate behav- energy use to be more in line with their neighbors. We review ior that occurs in a group context. Sherif and Sherif [8] say new approaches examining the effects of norms stemming that social norms are ‘formed in group situations and from multiple groups, and utilizing normative referents to shift subsequently serve as standards for the individual’s per- behaviors in social networks. Though the focus of less research ception and judgment when he [sic] is not in the group in recent years, our review highlights the fundamental influence situation. The individual’s major social attitudes are of social norms on social behavior. formed in relation to group norms (pp. 202–203).’ Social norms, or group norms, are ‘regularities in attitudes and Address behavior that characterize a social group and differentiate Department of Psychology, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS 66045, it from other social groups’ [9 ] (p. -

Librarianship and the Philosophy of Information

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal) Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln July 2005 Librarianship and the Philosophy of Information Ken R. Herold Hamilton College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Herold, Ken R., "Librarianship and the Philosophy of Information" (2005). Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal). 27. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/27 Library Philosophy and Practice Vol. 3, No. 2 (Spring 2001) (www.uidaho.edu/~mbolin/lppv3n2.htm) ISSN 1522-0222 Librarianship and the Philosophy of Information Ken R. Herold Systems Manager Burke Library Hamilton College Clinton, NY 13323 “My purpose is to tell of bodies which have been transformed into shapes of a different kind.” Ovid, Metamorphoses Part I. Library Philosophy Provocation Information seems to be ubiquitous, diaphanous, a-categorical, discrete, a- dimensional, and knowing. · Ubiquitous. Information is ever-present and pervasive in our technology and beyond in our thinking about the world, appearing to be a generic ‘thing’ arising from all of our contacts with each other and our environment, whether thought of in terms of communication or cognition. For librarians information is a universal concept, at its greatest extent total in content and comprehensive in scope, even though we may not agree that all information is library information. · Diaphanous. Due to its virtuality, the manner in which information has the capacity to make an effect, information is freedom. In many aspects it exhibits a transparent quality, a window-like clarity as between source and patron in an ideal interface or a perfect exchange without bias. -

The Use of Silence As a Political Rhetorical Strategy (TITLE)

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 2003 The seU of Silence as a Political Rhetorical Strategy Timothy J. Anderson Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in Speech Communication at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Anderson, Timothy J., "The sU e of Silence as a Political Rhetorical Strategy" (2003). Masters Theses. 1434. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/1434 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THESIS/FIELD EXPERIENCE PAPER REPRODUCTION CERTIFICATE TO: Graduate Degree Candidates (who have written formal theses) SUBJECT: Permission to Reproduce Theses The University Library is receiving a number of request from other institutions asking permission to reproduce dissertations for inclusion in their library holdings. Although no copyright laws are involved, we feel that professional courtesy demands that permission be obtained from the author before we allow these to be copied. PLEASE SIGN ONE OF THE FOLLOWING STATEMENTS: Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University has my permission to lend my thesis to a reputable college or university for the purpose of copying it for inclusion in that institution's library~r research holdings. Date I respectfully request Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University NOT allow my thesis to be reproduced because: Author's Signature Date thesis4.form The Use of Silence as a Political Rhetorical Strategy (TITLE) BY Timothy J. -

Notes on Pragmatism and Scientific Realism Author(S): Cleo H

Notes on Pragmatism and Scientific Realism Author(s): Cleo H. Cherryholmes Source: Educational Researcher, Vol. 21, No. 6, (Aug. - Sep., 1992), pp. 13-17 Published by: American Educational Research Association Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1176502 Accessed: 02/05/2008 14:02 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=aera. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We enable the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org Notes on Pragmatismand Scientific Realism CLEOH. CHERRYHOLMES Ernest R. House's article "Realism in plicit declarationof pragmatism. Here is his 1905 statement ProfessorResearch" (1991) is informative for the overview it of it: of scientificrealism. -

'The Magic That Can Set You Free': the Ideology of Folk and the Myth of the Rock Community

The magic that can set you free': the ideology of folk and the myth of the rock community by SIMON FRITH Rock, the saying goes, is 'the folk music of our time'. Not from a sociological point of view. If 'folk' describes pre-capitalist modes of music production, rock is, without a doubt, a mass-produced, mass- consumed, commodity. The rock-folk argument, indeed, is not about how music is made, but about how it works: rock is taken to express (or reflect) a way of life; rock is used by its listeners as a folk music - it articulates communal values, comments on shared social problems. The argument, in other words, is about subcultures rather than music- making; the question of how music comes to represent its listeners is begged. (I develop these arguments further in Frith 1978, pp. 191-202, and, with particular reference to punk rock, in Frith 1980.) In this article I am not going to answer this question either. My concern is not whether rock is or is not a folk music, but is with the effects of a particular account of popular culture - the ideology of folk - on rock's interpretation of itself. For the rock ideologues of the 1960s - musicians, critics and fans alike - rock 'n' roll's status as a folk music was what differentiated it from routine pop; it was as a folk music that rock could claim a distinctive political and artistic edge. The argument was made, for example, by Jon Landau in his influential role as reviews editor and house theorist of Rolling Stone. -

Persuasive Communication and Advertising Efficacy for Public Health Policy: a Critical Approach

Persuasive communication and advertising efficacy for public health policy : A critical approach. Vincent Coppola, Odile Camus To cite this version: Vincent Coppola, Odile Camus. Persuasive communication and advertising efficacy for public health policy : A critical approach.. 2009. halshs-00410054 HAL Id: halshs-00410054 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00410054 Preprint submitted on 17 Aug 2009 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Communication Research Persuasive communication and advertising efficacy for public health policy: a critical approach For Peer Review Journal: Communication Research Manuscript ID: CR-09-118 Manuscript Type: Original Research Article Persuasive communication, Pragmatics, Social advertising, Health Keywords: communication Our study is at the juncture of two themes largely investigated by researchers in communication, namely persuasion and pragmatics. First, we recall some tenets of these two topics. In particular, we refer to the dual process theories of the persuasion and the inferential model of pragmatics. Second we develop the argument that studies in persuasive communication have been undertaken Abstract: until now within the Encoding/Decoding paradigm without considering enough the main ideas of the pragmatics and intentionalist paradigm about communication and language. -

The “Ambiguity” Fallacy

\\jciprod01\productn\G\GWN\88-5\GWN502.txt unknown Seq: 1 2-SEP-20 11:10 The “Ambiguity” Fallacy Ryan D. Doerfler* ABSTRACT This Essay considers a popular, deceptively simple argument against the lawfulness of Chevron. As it explains, the argument appears to trade on an ambiguity in the term “ambiguity”—and does so in a way that reveals a mis- match between Chevron criticism and the larger jurisprudence of Chevron critics. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ................................................. 1110 R I. THE ARGUMENT ........................................ 1111 R II. THE AMBIGUITY OF “AMBIGUITY” ..................... 1112 R III. “AMBIGUITY” IN CHEVRON ............................. 1114 R IV. RESOLVING “AMBIGUITY” .............................. 1114 R V. JUDGES AS UMPIRES .................................... 1117 R CONCLUSION ................................................... 1120 R INTRODUCTION Along with other, more complicated arguments, Chevron1 critics offer a simple inference. It starts with the premise, drawn from Mar- bury,2 that courts must interpret statutes independently. To this, critics add, channeling James Madison, that interpreting statutes inevitably requires courts to resolve statutory ambiguity. And from these two seemingly uncontroversial premises, Chevron critics then infer that deferring to an agency’s resolution of some statutory ambiguity would involve an abdication of the judicial role—after all, resolving statutory ambiguity independently is what judges are supposed to do, and defer- ence (as contrasted with respect3) is the opposite of independence. As this Essay explains, this simple inference appears fallacious upon inspection. The reason is that a key term in the inference, “ambi- guity,” is critically ambiguous, and critics seem to slide between one sense of “ambiguity” in the second premise of the argument and an- * Professor of Law, Herbert and Marjorie Fried Research Scholar, The University of Chi- cago Law School. -

Begging the Question/Circular Reasoning Caitlyn Nunn, Chloe Christensen, Reece Taylor, and Jade Ballard Definition

Begging the Question/Circular Reasoning Caitlyn Nunn, Chloe Christensen, Reece Taylor, and Jade Ballard Definition ● A (normally) comical fallacy in which a proposition is backed by a premise or premises that are backed by the same proposition. Thus creating a cycle where no new or useful information is shared. Universal Example ● “Pvt. Joe Bowers: What are these electrolytes? Do you even know? Secretary of State: They're... what they use to make Brawndo! Pvt. Joe Bowers: But why do they use them to make Brawndo? Secretary of Defense: [raises hand after a pause] Because Brawndo's got electrolytes” (Example from logically fallicious.com from the movie Idiocracy). Circular Reasoning in The Crucible Quote: One committing the fallacy: Elizabeth Hale: But, woman, you do believe there are witches in- Explanation: Elizabeth believes that Elizabeth: If you think that I am one, there are no witches in Salem because then I say there are none. she knows that she is not a witch. She doesn’t think that she’s a witch (p. 200, act 2, lines 65-68) because she doesn’t believe that there are witches in Salem. And so on. More examples from The Crucible Quote: One committing the fallacy: Martha Martha Corey: I am innocent to a witch. I know not what a witch is. Explanation: This conversation Hawthorne: How do you know, then, between Martha and Hathorne is an that you are not a witch? example of begging the question. In Martha Corey: If I were, I would know it. Martha’s answer to Judge Hathorne, she uses false logic. -

Managing Social Norms for Persuasive Impact

SOCIAL INFLUENCE, 2006, 1 (1), 3–15 Managing social norms for persuasive impact Robert B. Cialdini and Linda J. Demaine Arizona State University, USA Brad J. Sagarin Northern Illinois University, USA Daniel W. Barrett Western Connecticut State University, USA Kelton Rhoads University of Southern California, USA Patricia L. Winter US Forest Service, CA, USA In order to mobilise action against a social problem, public service communicators often include normative information in their persuasive appeals. Such messages can be either effective or ineffective because they can normalise either desirable or undesirable conduct. To examine the implications in an environmental context, visitors to Arizona’s Petrified Forest National Park were exposed to messages that admonished against the theft of petrified wood. In addition, the messages conveyed information either about descriptive norms (the levels of others’ behaviour) or injunctive norms (the levels of others’ disapproval) regarding such thievery. Results showed that focusing message recipients on descriptive normative information was most likely to increase theft, whereas focusing them on injunctive normative information was most likely to suppress it. Recommendations are offered for optimising the impact of normative messages in situations characterised by objectionable levels of undesirable conduct. After decades of debate concerning their causal impact, (e.g., Berkowitz, 1972; Darley & Latane´, 1970; Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975; Krebs, 1970; Krebs & Address correspondence to: Robert B. Cialdini, Department of Psychology, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ 85287-1104, USA. Email: [email protected] This research was partially funded through grants from the United States Forest Service (PSW-96-0022CA) and the Arizona Department of Environmental Quality (No.-98-154C/97- 0152AI). -

Some Common Fallacies of Argument Evading the Issue: You Avoid the Central Point of an Argument, Instead Drawing Attention to a Minor (Or Side) Issue

Some Common Fallacies of Argument Evading the Issue: You avoid the central point of an argument, instead drawing attention to a minor (or side) issue. ex. You've put through a proposal that will cut overall loan benefits for students and drastically raise interest rates, but then you focus on how the system will be set up to process loan applications for students more quickly. Ad hominem: Here you attack a person's character, physical appearance, or personal habits instead of addressing the central issues of an argument. You focus on the person's personality, rather than on his/her ideas, evidence, or arguments. This type of attack sometimes comes in the form of character assassination (especially in politics). You must be sure that character is, in fact, a relevant issue. ex. How can we elect John Smith as the new CEO of our department store when he has been through 4 messy divorces due to his infidelity? Ad populum: This type of argument uses illegitimate emotional appeal, drawing on people's emotions, prejudices, and stereotypes. The emotion evoked here is not supported by sufficient, reliable, and trustworthy sources. Ex. We shouldn't develop our shopping mall here in East Vancouver because there is a rather large immigrant population in the area. There will be too much loitering, shoplifting, crime, and drug use. Complex or Loaded Question: Offers only two options to answer a question that may require a more complex answer. Such questions are worded so that any answer will implicate an opponent. Ex. At what point did you stop cheating on your wife? Setting up a Straw Person: Here you address the weakest point of an opponent's argument, instead of focusing on a main issue.