Phylogenetic Relationships Among Megabats, Microbats, and Primates (Molecular Systematics/Chiroptera/Sequence Lint/Rates of Evolution) DAVID P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bat Conservation 2021

Bat Conservation Global evidence for the effects of interventions 2021 Edition Anna Berthinussen, Olivia C. Richardson & John D. Altringham Conservation Evidence Series Synopses 2 © 2021 William J. Sutherland This document should be cited as: Berthinussen, A., Richardson O.C. and Altringham J.D. (2021) Bat Conservation: Global Evidence for the Effects of Interventions. Conservation Evidence Series Synopses. University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK. Cover image: Leucistic lesser horseshoe bat Rhinolophus hipposideros hibernating in a former water mill, Wales, UK. Credit: Thomas Kitching Digital material and resources associated with this synopsis are available at https://www.conservationevidence.com/ 3 Contents Advisory Board.................................................................................... 11 About the authors ............................................................................... 12 Acknowledgements ............................................................................. 13 1. About this book ........................................................... 14 1.1 The Conservation Evidence project ................................................................................. 14 1.2 The purpose of Conservation Evidence synopses ............................................................ 14 1.3 Who this synopsis is for ................................................................................................... 15 1.4 Background ..................................................................................................................... -

Daytime Behaviour of the Grey-Headed Flying Fox Pteropus Poliocephalus Temminck (Pteropodidae: Megachiroptera) at an Autumn/Winter Roost

DAYTIME BEHAVIOUR OF THE GREY-HEADED FLYING FOX PTEROPUS POLIOCEPHALUS TEMMINCK (PTEROPODIDAE: MEGACHIROPTERA) AT AN AUTUMN/WINTER ROOST K.A. CONNELL, U. MUNRO AND F.R. TORPY Connell KA, Munro U and Torpy FR, 2006. Daytime behaviour of the grey-headed flying fox Pteropus poliocephalus Temminck (Pteropodidae: Megachiroptera) at an autumn/winter roost. Australian Mammalogy 28: 7-14. The grey-headed flying fox (Pteropus poliocephalus Temminck) is a threatened large fruit bat endemic to Australia. It roosts in large colonies in rainforest patches, mangroves, open forest, riparian woodland and, as native habitat is reduced, increasingly in vegetation within urban environments. The general biology, ecology and behaviour of this bat remain largely unknown, which makes it difficult to effectively monitor, protect and manage this species. The current study provides baseline information on the daytime behaviour of P. poliocephalus in an autumn/winter roost in urban Sydney, Australia, between April and August 2003. The most common daytime behaviours expressed by the flying foxes were sleeping (most common), grooming, mating/courtship, and wing spreading (least common). Behaviours differed significantly between times of day and seasons (autumn and winter). Active behaviours (i.e., grooming, mating/courtship, wing spreading) occurred mainly in the morning, while sleeping predominated in the afternoon. Mating/courtship and wing spreading were significantly higher in April (reproductive period) than in winter (non-reproductive period). Grooming was the only behaviour that showed no significant variation between sample periods. These results provide important baseline data for future comparative studies on the behaviours of flying foxes from urban and ‘natural’ camps, and the development of management strategies for this species. -

Bird and Bat Conservation Strategy

Searchlight Wind Energy Project FEIS Appendix B 18B Appendix B-4: Bird and Bat Conservation Strategy Page | B Searchlight Bird and Bat Conservation Strategy Searchlight Wind Energy Project Bird and Bat Conservation Strategy Prepared for: Duke Energy Renewables 550 South Tryon Street Charlotte, North Carolina 28202 Prepared by: Tetra Tech EC, Inc. 1750 SW Harbor Way, Suite 400 Portland, OR 97201 November 2012 Searchlight BBCS i October 2012 Searchlight Bird and Bat Conservation Strategy TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................ 6 1.1 Duke Energy Renewables‘ Corporate Policy .......................................................... 6 1.2 Statement of Purpose ............................................................................................ 6 2.0 BACKGROUND AND DESCRIPTION OF THE PROJECT ............................................. 6 3.0 PROJECT-SPECIFIC REGULATORY REQUIREMENTS .............................................11 3.1 Potential Endangered Species Act-Listed Wildlife Species ...................................11 3.2 Migratory Bird Treaty Act ......................................................................................11 3.3 Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act ..................................................................12 3.4 Nevada State Codes .............................................................................................12 4.0 DECISION FRAMEWORK .............................................................................................12 -

Chiroptera: Pteropodidae)

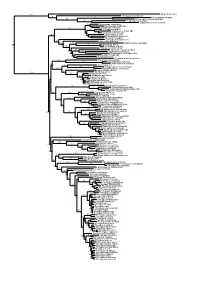

Chapter 6 Phylogenetic Relationships of Harpyionycterine Megabats (Chiroptera: Pteropodidae) NORBERTO P. GIANNINI1,2, FRANCISCA CUNHA ALMEIDA1,3, AND NANCY B. SIMMONS1 ABSTRACT After almost 70 years of stability following publication of Andersen’s (1912) monograph on the group, the systematics of megachiropteran bats (Chiroptera: Pteropodidae) was thrown into flux with the advent of molecular phylogenetics in the 1980s—a state where it has remained ever since. One particularly problematic group has been the Austromalayan Harpyionycterinae, currently thought to include Dobsonia and Harpyionycteris, and probably also Aproteles.Inthis contribution we revisit the systematics of harpyionycterines. We examine historical hypotheses of relationships including the suggestion by O. Thomas (1896) that the rousettine Boneia bidens may be related to Harpyionycteris, and report the results of a series of phylogenetic analyses based on new as well as previously published sequence data from the genes RAG1, RAG2, vWF, c-mos, cytb, 12S, tVal, 16S,andND2. Despite a striking lack of morphological synapomorphies, results of our combined analyses indicate that Boneia groups with Aproteles, Dobsonia, and Harpyionycteris in a well-supported, expanded Harpyionycterinae. While monophyly of this group is well supported, topological changes within this clade across analyses of different data partitions indicate conflicting phylogenetic signals in the mitochondrial partition. The position of the harpyionycterine clade within the megachiropteran tree remains somewhat uncertain. Nevertheless, biogeographic patterns (vicariance-dispersal events) within Harpyionycterinae appear clear and can be directly linked to major biogeographic boundaries of the Austromalayan region. The new phylogeny of Harpionycterinae also provides a new framework for interpreting aspects of dental evolution in pteropodids (e.g., reduction in the incisor dentition) and allows prediction of roosting habits for Harpyionycteris, whose habits are unknown. -

Figs1 ML Tree.Pdf

100 Megaderma lyra Rhinopoma hardwickei 71 100 Rhinolophus creaghi 100 Rhinolophus ferrumequinum 100 Hipposideros armiger Hipposideros commersoni 99 Megaerops ecaudatus 85 Megaerops niphanae 100 Megaerops kusnotoi 100 Cynopterus sphinx 98 Cynopterus horsfieldii 69 Cynopterus brachyotis 94 50 Ptenochirus minor 86 Ptenochirus wetmorei Ptenochirus jagori Dyacopterus spadiceus 99 Sphaerias blanfordi 99 97 Balionycteris maculata 100 Aethalops alecto 99 Aethalops aequalis Thoopterus nigrescens 97 Alionycteris paucidentata 33 99 Haplonycteris fischeri 29 Otopteropus cartilagonodus Latidens salimalii 43 88 Penthetor lucasi Chironax melanocephalus 90 Syconycteris australis 100 Macroglossus minimus 34 Macroglossus sobrinus 92 Boneia bidens 100 Harpyionycteris whiteheadi 69 Harpyionycteris celebensis Aproteles bulmerae 51 Dobsonia minor 100 100 80 Dobsonia inermis Dobsonia praedatrix 99 96 14 Dobsonia viridis Dobsonia peronii 47 Dobsonia pannietensis 56 Dobsonia moluccensis 29 Dobsonia anderseni 100 Scotonycteris zenkeri 100 Casinycteris ophiodon 87 Casinycteris campomaanensis Casinycteris argynnis 99 100 Eonycteris spelaea 100 Eonycteris major Eonycteris robusta 100 100 Rousettus amplexicaudatus 94 Rousettus spinalatus 99 Rousettus leschenaultii 100 Rousettus aegyptiacus 77 Rousettus madagascariensis 87 Rousettus obliviosus Stenonycteris lanosus 100 Megaloglossus woermanni 100 91 Megaloglossus azagnyi 22 Myonycteris angolensis 100 87 Myonycteris torquata 61 Myonycteris brachycephala 33 41 Myonycteris leptodon Myonycteris relicta 68 Plerotes anchietae -

Is Bat Hair Morphology Exceptional?

Vespertilio 17: 171–183, 2014 ISSN 1213-6123 Is bat hair morphology exceptional? Britten D. SESSIONS1, Chanell E. Nielson2, John M. SOWA3, Wilford M. HESS4, Wesley “Skip” Skidmore5 & Bradley A. Carmack6 1 Patent Attorney, Zilka-Kotab, 1155 N. First Street Ste. 105, San Jose, CA 95112, U.S.A.; [email protected] 2 Department of English, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT 84602, U.S.A. 3 Department of Chemical Engineering, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT 84602, U.S.A. 4 Department of Plant and Wildlife Sciences, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT 84602, U.S.A. 5 Life Sciences Museum, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT 84602, U.S.A. 6 HR Professional, Sunnyvale, CA 94089, U.S.A. Abstract. Surface hair scale patterns from 19 bat species (families Vespertilionidae and Molossidae) from Utah were studied using scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Hair width, scale length, pattern, and position in relation to the long axis were used to characterize morphology within species, and fa- milies within the order Chiroptera. Previous studies indicate variations within families. Hair morphology results make it evident that large variations and similarities within the families can be seen visually and codified for the order. In the family Vespertilionidae, variations in hair morphology necessitated better terminology, including two new terms for morphology patterns. In the family Molossidae, distinctions between species, and possibly within the family, may be evident using SEM imaging to characterize morphology characteristics, although only two species were studied in this family. More precise morpho- logical measurements than used for this study may be necessary to construct useful keys for species within at least some families of bat. -

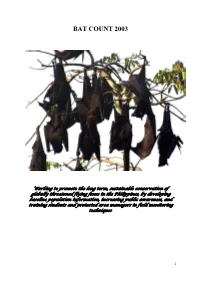

Bat Count 2003

BAT COUNT 2003 Working to promote the long term, sustainable conservation of globally threatened flying foxes in the Philippines, by developing baseline population information, increasing public awareness, and training students and protected area managers in field monitoring techniques. 1 A Terminal Report Submitted by Tammy Mildenstein1, Apolinario B. Cariño2, and Samuel Stier1 1Fish and Wildlife Biology, University of Montana, USA 2Silliman University and Mt. Talinis – Twin Lakes Federation of People’s Organizations, Diputado Extension, Sibulan, Negros Oriental, Philippines Photo by: Juan Pablo Moreiras 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Large flying foxes in insular Southeast Asia are the most threatened of the Old World fruit bats due to deforestation, unregulated hunting, and little conservation commitment from local governments. Despite the fact they are globally endangered and play essential ecological roles in forest regeneration as seed dispersers and pollinators, there have been only a few studies on these bats that provide information useful to their conservation management. Our project aims to promote the conservation of large flying foxes in the Philippines by providing protected area managers with the training and the baseline information necessary to design and implement a long-term management plan for flying foxes. We focused our efforts on the globally endangered Philippine endemics, Acerodon jubatus and Acerodon leucotis, and the bats that commonly roost with them, Pteropus hypomelanus, P. vampyrus lanensis, and P. pumilus which are thought to be declining in the Philippines. Local participation is an integral part of our project. We conducted the first national training workshop on flying fox population counts and conservation at the Subic Bay area. -

Anatomy and Histology of the Heart in Egyptian Fruit

Journal of Entomology and Zoology Studies 2016; 4(5): 50-56 E-ISSN: 2320-7078 P-ISSN: 2349-6800 JEZS 2016; 4(5): 50-56 Anatomy and histology of the heart in Egyptian © 2016 JEZS fruit bat (Rossetus aegyptiacus) Received: 09-09-2016 Accepted: 10-10-2016 Bahareh Alijani Bahareh Alijani and Farangis Ghassemi Department of Biology, Jahrom branch, Islamic Azad University, Abstract Jahrom, Iran This study was conducted to obtain more information about bats to help their conservation. Since 5 fruit Farangis Ghassemi bats, Rossetus aegyptiacus, weighing 123.04±0.08 g were captured using mist net. They were Department of Biology, Jahrom anesthetized and dissected in animal lab. The removed heart components were measured, fixed, and branch, Islamic Azad University, tissue processing was done. The prepared sections (5 µm) were subjected to Haematoxylin and Eosin Jahrom, Iran stain, and mounted by light microscope. Macroscopic and microscopic features of specimens were examined, and obtained data analyzed by ANOVA test. The results showed that heart was oval and closed in the transparent pericardium. The left and right side of heart were different significantly in volume and wall thickness of chambers. Heart was large and the heart ratio was 1.74%. Abundant fat cells, intercalated discs, and purkinje cells were observed. According to these results, heart in this species is similar to the other mammals and observed variation, duo to the high metabolism and energy requirements for flight. Keywords: Heart, muscle, bat, flight, histology 1. Introduction Bats are the only mammals that are able to fly [1]. Due to this feature, the variation in the [2, 3] morphology and physiology of their organs such as cardiovascular organs is expected Egyptian fruit bat (Rossetus aegyptiacus) belongs to order megachiroptera and it is the only megabat in Iran [4]. -

The Philippine Flying Foxes, Acerodon Jubatus and Pteropus Vampyrus Lanensis

Journal of Mammalogy, 86(4):719- 728, 2005 DIETARY HABITS OF THE WORLD’S LARGEST BATS: THE PHILIPPINE FLYING FOXES, ACERODON JUBATUS AND PTEROPUS VAMPYRUS LANENSIS Sam C. Stier* and Tammy L. M ildenstein College of Forestry and Conservation, University of Montana, Missoula, MT 59802, USA The endemic and endangered golden- crowned flying fox (Acerodon jubatus) coroosts with the much more common and widespread giant Philippine fmit bat (Pteropus vampyrus ianensis) in lowland dipterocarp forests throughout the Philippine Islands. The number of these mixed roost- colonies and the populations of flying foxes in them have declined dramatically in the last century. We used fecal analysis, interviews of bat hunters, and personal observations to describe the dietary habits of both bat species at one of the largest mixed roosts remaining, near Subic Bay, west- central Luzon. Dietary items were deemed “important” if used consistently on a seasonal basis or throughout the year, ubiquitously throughout the population, and if they were of clear nutritional value. Of the 771 droppings examined over a 2.5 -year period (1998-2000), seeds from Ficus were predominant in the droppings of both species and met these criteria, particularly hemiepiphytic species (41% of droppings of A. jubatus) and Ficus variegata (34% of droppings of P. v. ianensis and 22% of droppings of A. jubatus). Information from bat hunter interviews expanded our knowledge of the dietary habits of both bat species, and corroborated the fecal analyses and personal observations. Results from this study suggest that A. jubatus is a forest obligate, foraging on fruits and leaves from plant species restricted to lowland, mature natural forests, particularly using a small subset of hemiepiphytic and other Ficus species throughout the year. -

Calculate the Value of Bats

Calculate the Value of Bats Background One of the best ways to persuade people to protect bats is to explain EXPLORATION QUESTION “Why are bats important to our how many insects bats can eat. Scientists have discovered that economy and to our natural some small bats can catch up to 1,000 or more small insects in a world?” single hour. A nursing mother bat eats the most – sometimes catching more than 4,000 insects in a night. MATERIALS Little brown bats (myotis lucifugus) eat a wide variety of insects, Pencils including pests such as mosquitoes, moths, and beetles. If each little Activity Sheets A and B brown bat in your neighborhood had 500 mosquitoes in its evening Calculator (optional) meal, how many would a colony of 100 bats eat? By multiplying the OVERVIEW average number eaten (500) times the number of bats in the colony There are many reasons for (100), we calculate that this colony would eat 50,000 mosquitoes in students to care about bats. They an evening (500 x 100 = 50,000)! are fascinating and beautiful Using a calculator and multiplying 50,000 mosquitoes times 30 days animals. In this activity, students (the average number of days in a month), you can calculate that will use math skills to learn about these same bats could eat 1.5 million mosquitoes in a month (50,000 the ecological and economic x 30 = 1,500,000), not to mention the many other insects they would impacts of bats. Students will also catch! use communication skills to convey the importance of bats to Do bats really eat billions of bugs? our economy and natural world Bracken Cave, just north of San Antonio, Texas, is home to about 20 and the potential effects of White- million Mexican free-tailed bats. -

Are Megabats Flying Primates? Contrary Evidence from a Mitochondrial DNA Sequence

Aust. J. Bioi. Sci., 1988, 41, 327-32 Are Megabats Flying Primates? Contrary Evidence from a Mitochondrial DNA Sequence S. Bennett,A L. J. Alexander,A R. H. CrozierB,c and A. G. MackinlayA,c A School of Biochemistry, University of New South Wales, P.O. Box 1, Kensington, N.S.W. 2033. B School of Biological Science, University of New South Wales, P.O. Box 1, Kensington, N.S.W. 2033. C To whom reprint requests should be addressed. Abstract Bats (Chiroptera) are divided into the suborders Megachiroptera (fruit bats, 'megabats') and Micro chiroptera (predominantly insectivores, 'microbats'). It had been found that megabats and primates share a connection system between the retina and the midbrain not seen in microbats or other eutherian mammals, and challenging but plausible hypotheses were made that (a) bats are diphyletic and (b) megabats are flying primates. We obtained two DNA sequences from the mitochondrion of the fruit bat Pteropus poliocephalus, and performed phylogenetic analyses using the bat sequences in conjunction with homologous Drosophila, mouse, cow and human sequences. Two trees stand out as significantly more likely than any other; neither of these links the bat and human as the closest sequences. These results cast considerable doubt on the hypothesis that megabats are particularly close to primates. Introduction Various phylogenetic schemes based on morphology have linked bats and primates, such as in McKenna's (1975) grandorder Archonta, which also includes the Dermoptera (flying lemurs) and Scandentia (tree shrews). Molecular systematists, using immunological comparisons and amino acid sequences, have found that bats are not placed particularly close to primates, and that they are not diphyletic (Cronin and Sarich 1980; Dene et al. -

“Microbats Are in My House”!

“MICROBATS ARE IN MY HOUSE”! Answers to frequently asked questions about microbats in houses. Bats are ancient animals that have been around for about 50 million years. Australia has six families of microbats containing 58 species. Because microbats are small, nocturnal animals most people are unaware of this native Australian mammal. They are specifically adapted for flying and can have a wing span measuring up to 25cm. These little mammals use both eyesight and echolocation to fly at night in When hollow trees are cut down entire search of food. Microbats are gentle mammals but families of bats are misplaced. Habitat may bite if they feel frightened, threatened loss can lead to regional extinctions of microbats. Photo: Louise Saunders or are injured. Please be mindful that they have very delicate finger bones in their wings. Photograph: In the veranda support beams; Nyctophilus “WHAT ABOUT MY HEALTH? DON’T THEY gouldi ~ Gould’s long-eared bat. Photo- © Dr Les Hall. A good location, happy bats and happy humans. CARRY DISEASE?” Microbats are not a threat to human health if you do not handle them, especially not with BARE hands. Only three species of microbat have been identified with Australian Bat Lyssavirus (ABLV). There have only been two fatal cases of Lyssavirus in Australia affecting humans, one in 1996 and one in 1998; the 1996 case was associated with a bite from a microbat to a wildlife carer. Since then all bat carers must have pre-exposure vaccinations to enable them to rescue and care for bats safely. ABLV is an extremely rare, but fatal disease.