Composer David Lyon: an Autobiography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Don Giovanni Sweeney Todd

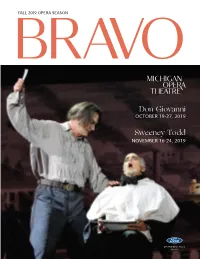

FALL 2019 OPERA SEASON B R AVO Don Giovanni OCTOBER 19-27, 2019 Sweeney Todd NOVEMBER 16-24, 2019 2019 Fall Opera Season Sponsor e Katherine McGregor Dessert Parlor …at e Whitney. Named a er David Whitney’s daughter, Katherine Whitney McGregor, our intimate dessert parlor on the Mansion’s third oor features a variety of decadent cakes, tortes, and miniature desserts. e menu also includes chef-prepared specialties, pies, and “Drinkable Desserts.” Don’t miss the amazing aming dessert station featuring Bananas Foster and Cherries Jubilee. Reserve tonight’s table online at www.thewhitney.com or call 313-832-5700 4421 Woodward Ave., Detroit Pre- eater Menu Available on performance date with today’s ticket. Choose one from each course: FIRST COURSE Caesar Side Salad Chef’s Soup of the Day e Whitney Duet MAIN COURSE Grilled Lamb Chops Lake Superior White sh Pan Roasted “Brick” Chicken Sautéed Gnocchi View current menus DESSERT and reserve online at Chocolate Mousse or www.thewhitney.com Mixed Berry Sorbet with Fresh Berries or call 313-832-5700 $39.95 4421 Woodward Ave., Detroit e Katherine McGregor Dessert Parlor …at e Whitney. Named a er David Whitney’s daughter, Katherine Whitney McGregor, our intimate dessert parlor on the Mansion’s third oor features a variety of decadent cakes, tortes, and miniature desserts. e menu also includes chef-prepared specialties, pies, and “Drinkable Desserts.” Don’t miss the amazing aming dessert station featuring Bananas Foster and Cherries Jubilee. Reserve tonight’s table online at www.thewhitney.com or call 313-832-5700 4421 Woodward Ave., Detroit Pre- eater Menu Available on performance date with today’s ticket. -

Walton - a List of Works & Discography

SIR WILLIAM WALTON - A LIST OF WORKS & DISCOGRAPHY Compiled by Martin Rutherford, Penang 2009 See end for sources and legend. Recording Venue Time Date Orchestra Conductor Performers No. Coy Co Catalogue No F'mat St Rel A BIRTHDAY FANFARE Description For Seven Trumpets and Percussion Completion 1981, Ischia Dedication For Karl-Friedrich Still, a neighbour on Ischia, on his 70th birthday First Performances Type Date Orchestra Conductor Performers Recklinghausen First 10-Oct-81 Westphalia SO Karl Rickenbacher Royal Albert Hall L'don 7-Jun-82 Kneller Hall G E Evans A LITANY - ORIGINAL VERSION Description For Unaccompanied Mixed Voices Completion Easter, 1916 Oxford First Performances Type Date Orchestra Conductor Performers Unknown Recording Venue Time Date Orchestra Conductor Performers No. Coy Co Cat No F'mat St Rel Hereford Cathedral 3.03 4-Jan-02 Stephen Layton Polyphony 01a HYP CDA 67330 CD S Jun-02 A LITANY - FIRST REVISION Description First revision by the Composer Completion 1917 First Performances Type Date Orchestra Conductor Performers Unknown Recording Venue Time Date Orchestra Conductor Performers No. Coy Co Cat No F'mat St Rel Hereford Cathedral 3.14 4-Jan-02 Stephen Layton Polyphony 01a HYP CDA 67330 CD S Jun-02 A LITANY - SECOND REVISION Description Second revision by the Composer Completion 1930 First Performances Type Date Orchestra Conductor Performers Unknown Recording Venue Time Date Orchestra Conductor Performers No. Coy Co Cat No F'mat St Rel St Johns, Cambridge ? Jan-62 George Guest St Johns, Cambridge 01a ARG ZRG -

SEA EAGLE Works by Gerald Barry • Peter Maxwell Davies • Robin Holloway Colin Matthews • David Matthews • Mark-Anthony Turnage • Huw Watkins RICHARD WATKINS Horn

Richard Watkins horn with Mark Padmore tenor • Huw Watkins piano Paul Watkins cello • The Nash Ensemble SEA EAGLE works by Gerald Barry • Peter Maxwell Davies • Robin Holloway Colin Matthews • David Matthews • Mark-Anthony Turnage • Huw Watkins RICHARD WATKINS horn Peter Maxwell Davies: Sea Eagle 9’08 The Nash Ensemble 1 Adagio 4’05 Marianne Thorsen violin 2 Lento 3’33 3 Presto molto 1’30 Laura Samuel violin Lawrence Power viola Gerald Barry: Jabberwocky 5’44 4 Adrian Brendel cello with Mark Padmore tenor • Huw Watkins piano Saunders photo: Keith Colin Matthews: Three of a Kind 9’34 5 Vivo 1’47 6 Largamente 1’13 7 Calmo 6’34 with Paul Watkins cello • Huw Watkins piano 8 Huw Watkins: Trio 12’48 with Laura Samuel violin • Huw Watkins piano David Matthews: Quintet for Horn and Strings (live recording) 13’13 9 Andante 7’57 10 Molto vivace 5’16 The Nash Ensemble 11 Mark-Anthony Turnage: Prayer for a great man 3’57 with Paul Watkins cello Robin Holloway: Trio for Horn, Cello and Piano 20’08 12 I Liberamente 11’33 13 II Poco allegro 8’35 with Paul Watkins cello • Huw Watkins piano Total timing 75’29 2 SEA EAGLE Introduction by Richard Watkins Matthews and Holloway, it’s certainly years have played in several of his a winning one. chamber works, most notably with the Nash, so when I discovered that his I met Peter Maxwell Davies when I Horn Concerto, and after prolonged David Matthews’ first piece for solo Cello Concerto, written for the joined the Fires of London, my first negotiations, it finally came to fruition horn was his Capriccio for Two Horns brilliant Paul Watkins, had a short professional experience in 1981. -

A Centenary Celebration 100 Years of the London Chamber Orchestra

Available to stream online from 7:30pm, 7 May 2021 until midnight, 16 May 2021 A Centenary Celebration 100 years of the London Chamber Orchestra Programme With Christopher Warren-Green, conductor Handel Arrival of the Queen of Sheba Jess Gillam, presenter Mozart Divertimento in D Major, K205, I. Largo – Allegro Debussy Danses Sacrée et Profane Maconchy Concertino for Clarinet and Orchestra, III. Allegro Soloists Mozart Eine Kleine Nachtmusik, I. Allegro Anne Denholm, harp Britten Courtly Dance No. 5 Mark van de Wiel, clarinet Maxwell Davies Farewell to Stromness Various A Century of Music (premiere) Soloists, A Century of Music Elgar Introduction and Allegro Mary Bevan, soprano Pekka Kuusisto, violin London Chamber Orchestra Alison Balsom, trumpet Ksenija Sidorova, accordion Violin 1 Viola Flute & Piccolo Benjamin Beilman, violin Clio Gould Rosemary Warren-Green Harry Winstanley Jess Gillam, saxophone Manon Derome Kate Musker Gina McCormack Becky Low Oboe Sophie Lockett Jenny Coombes Gordon Hunt Imogen East Alison Alty Composers, A Century of Music Eunsley Park Cello Rob Yeomans Robert Max Clarinet & Bass Clarinet John Rutter Edward Bale Joely Koos Mark van de Wiel Freya Waley-Cohen Julia Graham Violin 2 Rachael Lander Bassoon Paul Max Edlin Charles Sewart Meyrick Alexander George Morton Anna Harpham Bass Alexandra Caldon Andy Marshall Horn Tim Jackson Guy Button Ben Daniel-Greep Richard Watkins Jo Godden Michael Thompson Gabriel Prokofiev Harriet Murray Percussion Cheryl Frances-Hoad Julian Poole Trumpet Ross Brown If you’re joining us in the virtual concert hall, we’d love to know about it! Tag us on your social media using the hashtag #LCOTogether George Frideric Handel Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Arrival of the Queen of Sheba Divertimento in D Major, K205 I. -

Fall Season Oct

2018-19 Concert Series SEP. 15 Philharmonia Boston Orchestra String Players NOV. 10 From Ella FALL SEASON Saturday, Sept. 15, 7:30 p.m. Jazz Band Lorimer Chapel Eric Thomas, director (Funded by the Robert J. Strider Concert Fund) Saturday, Nov. 10, 7:30 p.m. Founded in 2008, Philharmonia Boston Orchestra is Given Auditorium, Bixler Art and Music Center composed of professional musicians from the Greater We tour Ella Fitzgerald’s musical life, from her audition at Boston area. Their vision is to serve and inspire the the Apollo Theater to her work at the helm of the Chick Webb SEP. 15 OCT. 6 OCT. 27 community by engaging in educational outreach programs, Band, and give a special nod to her Live in Berlin album. “A providing vibrant musical experiences, and introducing young Tisket A Tasket,” “Black Coffee,” “Angel Eyes,” “I Can’t Give talented musicians. Led by Jinwook Park, Colby Symphony You Anything But Love,” “Mack the Knife,” and other classic Orchestra’s dynamic director, the PBO string players will tunes will be featured. We’ll also touch on hits from Nelson present works by Bartók, Respighi, and Tchaikovsky. Riddle, Ray Brown, Joe Pass, the Duke, and the Count, and some of the other artists she influenced. OCT. 6 Traditional Flamenco with Bourassa Dance and Friends Sandeep Das and the HUM Ensemble: NOV. 11 (Funded by the Clark/Comparetti Concert Fund) Delhi to Damascus NOV. 3 NOV. 17 Saturday, Oct. 6, 7:30 p.m. Sunday, Nov. 11, 3 p.m. Page Commons Room, Cotter Union Page Commons Room, Cotter Union Flamenco artists Lindsey Bourassa (dance), Barbara (Funded by the Robert J. -

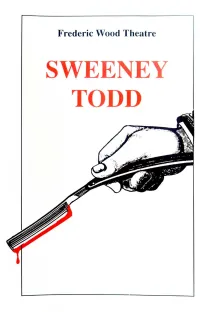

SWEENEY TODD University of British Columbia

Frederic Wood Theatr e SWEENEY TODD University of British Columbia Frederic Wood Theatre presents SWEENEY TODD Music and Lyrics by STEPHEN SONDHEIM During1990, UBC is marking its diamond anniversary . Book by HUGH WHEELER It's a time not only to reflect upon our past accomplishments, but to look ahead to our brightfuture. To commemorate this special year, the University is offering a Directed B y wide range of official souvenirs, available at the Bookstore. When you purchase a 75th Anniversary souvenir item, you'll be French Tickner helping to support campus-wide events. January 17 - February 3 BOOKSTORE 1990 6200 University Boulevard, Vancouver, V6T 1Y5 Telephone 228-4741 Illustration reproduced with permission from Canadian Graphics West Inc . Co-Producing "SWEENEY" artistic collaboration . The President's Campaign, supported b y If J.M Synge, the Irish dramatist, is correct in maintaining tha t the munificence of private donors and matching Provincial "all art is collaboration", then Theatre artistry, more than an y funds, will create a complex of performance spaces—concert other form, would seem to thrive on multiple collaborativ e hall, proscenium theatre, studio, and cinema—which wil l processes . The art of the actor, director, scenic and costume an d provide an extraordinary facility for Music, Theatre, Creative lighting designers, technical magicians and sound operators, al l Writing and Fine Arts to combine their collective expertise i n blend into an amalgam which must seem a fully integrate d joint ventures. In this sense, SWEENEY TODD is not only a whole. One of the great advantages of the University structure is celebration of the University's past achievement over the last 7 5 that this kind of collaborative opportunity can be extende d years, but a tribute to the foresight and planning which wil l beyond the workings of a single department to draw on th e make UBC pre-eminent among Canada's Creative an d expertise of a range of other disciplines . -

The Snow Queen

P a g e | 1 P a g e | 2 The Snow Queen CAST Greta, Principal Girl Kai, Greta’s brother Batty Bridget, Dame and landlady The Snow Queen, Elin Easter Bunny, Tyson Jingle & Jangle, comedy duo Glitter Dewberry, the Tooth Fairy Sandman Jack Frost, Principal Boy, the Snow Queen’s henchman Bobgoblin The Three Wise Witches, See No, Hear No, and Speak No Chorus & Yeti Scene – the Snow Queen’s palace, the Witches’ cave Time – long ago MUSICAL NUMBERS Song 1 Wake Up Smiling (Go! Go! Go!) – Greta, Kai and Chorus Song 2 Move Along (The All-American Rejects) – Greta, Bridget and Chorus Song 3 Cold As Ice (Foreigner) – Jack, Bobgoblin and Chorus Song 4 Mr Sandman (The Chordettes) – Sandman and Chorus Song 5 I Want To Know What Love Is (Foreigner) – Jack Song 6 Everything Is Awesome (Lego Movie) – Tyson, Greta, Glitter, Bridget, Sandman, Jingle, Jangle and Chorus Song 7 It May Be Winter Outside (Love Unlimited) – Tyson, Greta, Glitter, Bridget, Sandman, Jingle, Jangle and Chorus Song 8 I’ll Stand By You (The Pretenders) – Greta Song 9 I Put A Spell On You (Screamin Jay Hawkins/Hocus Pocus Movie) – Three Wise Witches Song 10 I See The Light (Tangled Movie) – Greta and Jack Song 11 Finest Hour (Sara Niemietz and Blake Ewing)– All except Snow Queen Song 12 Let It Go (Frozen movie) (just a section of it) – Snow Queen Song 13 The Sun Has Got Its Hat On – Audience participation Song 14 Walkdown – Wake Up Smiling Song 15 Let It Go – All P a g e | 3 ACT 1 Scene 1 Front of tabs The Voiceover is quite long, so could be either accompanied by a projection or acted out Voiceover Once upon a time in a land far, far north, there lived a young girl named Elin. -

The Snow Queen Educational Material LEGAL NOTICE the Snow Queen Educational Material

The Snow Queen Educational Material LEGAL NOTICE The Snow Queen Educational Material Redaction Deutsche Oper am Rhein Theatergemeinschaft Düsseldorf-Duisburg gGmbH Anja Fürstenberg, Anna-Mareike Vohn, Krysztina Winkel, Eleanor Siden, Junge Oper am Rhein Heinrich-Heine-Allee 16a 40213 Düsseldorf Tel. +49 (0)211.89 25-152 Fax +49 (0)211.89 25-289 [email protected] Adaptation in English by Elisabeth Lasky for OperaVision www.operavision.eu [email protected] Bibliography Hans Christian Andersen • Mönninghoff, Wolfgang : Das große Hans Christian Andersen Buch;, Düsseldorf und Zürich 2005 • Sahr Michael: Andersen lesen. Andersen Märchen für Schüler von heute; Hohengehren 1999 • http://hans-christian-andersen.de/ Marius Felix Lange • http://www.mariuslange.de/ • http://www.sikorski.de/4459/de/lange_marius_felix.html Sheet music and quotes from the book: Original score by Marius Felix Lange Pictures Hans Christian Andersen • http://hans-christian-andersen.de/ • https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hans_Christian_Andersen Production Pictures © Hans Jörg Michel © Deutsche Oper am Rhein 2018 – all rights reserved. 2 The Snow Queen Educational Material Contents Introduction – roles – the story ................................................................................................ 4 1. Context – the author, the composer and the fairy tale ............................................... 7 2. Improvisation - the characters of the opera ................................................................. 11 3. Character study- the trolls and the -

Juilliard AXIOM Program 02-02

AXIOM ii Behind every Juilliard artist is all of Juilliard —including you. With hundreds of dance, drama, and music performances, Juilliard is a wonderful place. When you join one of our membership programs, you become a part of this singular and celebrated community. by Claudio Papapietro Photo of cellist Khari Joyner Become a member for as little as $250 Join with a gift starting at $1,250 and and receive exclusive benefits, including enjoy VIP privileges, including • Advance access to tickets through • All Association benefits Member Presales • Concierge ticket service by telephone • 50% discount on ticket purchases and email • Invitations to special • Invitations to behind-the-scenes events members-only gatherings • Access to master classes, performance previews, and rehearsal observations (212) 799-5000, ext. 303 [email protected] juilliard.edu iii The Juilliard School presents AXIOM Jeffrey Milarsky, Conductor Friday, February 2, 2018, 7:30 Peter Jay Sharp Theater HANS Schnee, Ten Canons for Nine Instruments (2006–08) ABRAHAMSEN Canon 1a (b. 1952) Ruhig aber beweglich Canon 1b Fast immer zart und still Canon 2 Lustig spielend, aber nicht zu lustig, immer ein bisschen melancholisch Intermezzo 1 Canon 2b Lustig spielend, aber nicht zu lustig, immer ein bisschen melancholisch Canon 3a Ser langsam, schleppend und mit Trübsinn (im Tempo des “Tai Chi”) Canon 3b Ser langsam, schleppend und mit Trübsinn (im Tempo des “Tai Chi”) Intermezzo 2 (Program continues) Support for this performance is provided, in part, by the Muriel Gluck Production Fund. Please make certain that all electronic devices are turned off during the performance. The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment are not permitted in this auditorium. -

Stories from Hans Christian Andersen with Illustrations by Edmund Dulac Is a Publication of the Electronic Classics Series

Stories from Hans Christian Andersen with illustrations by Edmund Dulac An ELECTRONIC CLASSICS SERIES PUBLICATION Stories from Hans Christian Andersen with Illustrations by Edmund Dulac is a publication of The Electronic Classics Series. This Portable Document file is furnished free and without any charge of any kind. Any person using this document file, for any purpose, and in any way does so at his or her own risk. Neither the Pennsylvania State Uni- versity nor Jim Manis, Editor, nor anyone associated with the Pennsylvania State University assumes any responsi- bility for the material contained within the document or for the file as an electronic transmission, in any way. Stories from Hans Christian Andersen with Illustrations by Edmund Dulac, The Electronic Classics Series, Jim Manis, Editor, PSU-Hazleton, Hazleton, PA 18202 is a Portable Document File produced as part of an ongoing publica- tion project to bring classical works of literature, in En- glish, to free and easy access of those wishing to make use of them. Jim Manis is a faculty member of the English Department of The Pennsylvania State University. This page and any preceding page(s) are restricted by copyright. The text of the following pages are not copyrighted within the United States; however, the fonts used may be. Cover Design: Jim Manis; all images are by Edmund Dulac and are free of copyright restrictions within the United States Copyright © 2007 - 2013 The Pennsylvania State University is an equal opportunity university. Hans Christian Andersen Contents THE SNOW QUEEN ............................ 5 THE NIGHTINGALE ......................... 44 THE REAL PRINCESS ........................ 56 THE GARDEN OF PARADISE.......... -

Harrington's Pie and Mash Shop 3 Selkirk Road Tooting, London

Harrington’s Pie and Mash Shop 3 Selkirk Road Tooting, London. Open for business since 1908. RACHEL EDWARDS JENNY GERSTEN SEAVIEW PRODUCTIONS NATE KOCH, Executive Producer FIONA RUDIN BARROW STREET THEATRE JEAN DOUMANIAN REBECCA GOLD “A Customer!” present My name is Rachel Edwards and I am the originating producer of Tooting Arts Club’s Sweeney The Tooting Arts Club production of Todd. On behalf of myself, and my producing partners Jenny Gersten, Greg Nobile, Jana Shea and Nate Koch, it is our pleasure to welcome you to Harrington’s Pie and Mash Shop! In the spring of 1908, number 3 Selkirk Road Tooting, London, became the home of Harrington’s Pie and Mash shop when it was bought by Bertie Harrington and his wife Clara. Little has changed in this tiny Tooting eatery since it first opened for business some 109 years ago. The Harrington fam- ily still run the shop, the original green tiles still adorn the walls and the menu remains unchanged since the days of Queen Victoria. A Musical Thriller Music and Lyrics Book by The idea to stage Sweeney Todd in London’s oldest pie and mash shop was one which I lived with for several years before I dared to say it out loud. It felt too outrageous, too complicated, in essence – it felt impossible. A simple ‘yes’ from Beverley Mason – owner of Harrington’s, and great STEPHEN SONDHEIM HUGH WHEELER grand-daughter of Bertie and Clara – changed everything. Subsequently, an unforgettable collabora- tion was born that set in motion a chain of events that was nothing short of extraordinary. -

Dame Ethel Smyth's Concerto for Violin, Horn, and Orchestra: a Performance Guide for the Hornist

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1998 Dame Ethel Smyth's Concerto for Violin, Horn, and Orchestra: A Performance Guide for the Hornist. Janiece Marie Luedeke Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Luedeke, Janiece Marie, "Dame Ethel Smyth's Concerto for Violin, Horn, and Orchestra: A Performance Guide for the Hornist." (1998). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 6747. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/6747 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type o f computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps.