Juilliard AXIOM Program 02-02

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 the Roots of Birtwistle's Theatrical Expression

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-89534-7 - Harrison Birtwistle’s Operas and Music Theatre David Beard Excerpt More information 1 The roots of Birtwistle’s theatrical expression: from Pantomime to Down by the Greenwood Side With six major operas, around eight music dramas, and a body of incidental music to his name, Harrison Birtwistle has made a significant contribution to contemporary opera and music theatre during a period that spans more than forty years. This study is concerned not only to reflect the importance of these stage works by examining them in some detail but also to convey their varied musical and intellectual worlds. Previous studies have rightly focused on Birtwistle’s perennial concerns, such as myth, ritual, cyclical journeys, varied repetition, verse–refrain structures, instrumental role-play, layers and lines.1 These characteristics highlight consistency throughout Birtwistle’s oeuvre and are a mark of his formalist stance. By contrast, this book is motivated by a belief that the stage works – in which instrumental and physical drama, song and narrative are combined – demand interpre- tation from multiple, inter-disciplinary perspectives. While not denying obvious or important relations between works, what follows is rather more focused on differences: Birtwistle’s choice of contrasting narrative subjects, his collaborations with nine librettists, his varied pre-compositional ideas and working methods, his experience with different directors, producers and others, all distinguish one stage work from another. A recurring theme is therefore a consideration of ways in which Birtwistle’s initial concepts are informed, altered or conveyed differently in each case. Moreover, as ideas evolve, from the composer’s musical sketches to the final production, mul- tiple meanings accrue that are particular to each drama. -

Klsp2018iema Broschuere.Indd

KLANGSPUREN SCHWAZ INTERNATIONAL ENSEMBLE MODERN ACADEMY IN TIROL. REBECCA SAUNDERS COMPOSER IN RESIDENCE. 15TH EDITION 29.08. – 09.09.2018 KLANGSPUREN INTERNATIONAL ENSEMBLE MODERN ACADEMY 2018 KLANGSPUREN SCHWAZ is celebrating its 25th anniversary in 2018. The annual Tyrolean festival of contemporary music provides a stage for performances, encounters, and for the exploration and exchange of new musical ideas. With a different thematic focus each year, KLANGSPUREN aims to present a survey of the fascinating, diverse panorama that the music of our time boasts. KLANGSPUREN values open discourse, participation, and partnership and actively seeks encounters with locals as well as visitors from abroad. The entire beautiful region of Tyrol unfolds as the festival’s playground, where the most cutting-edge and modern forms of music as well as many young composers and musicians are presented. On the occasion of its own milestone anniversary – among other anniversaries that KLANGSPUREN SCHWAZ 2018 will be celebrating this year – the 25th edition of the festival has chosen the motto „Festivities. Places.“ (in German: „Feste. Orte.“). The program emphasizes projects and works that focus on aspects of celebrations, festivities, rituals, and events and have a specific reference to place and situation. KLANGSPUREN INTERNATIONAL ENSEMBLE MODERN ACADEMY is celebrating its 15th anniversary. The Academy is an offshoot of the renowned International Ensemble Modern Academy (IEMA) in Frankfurt and was founded in the same year as IEMA, in 2003. The Academy is central to KLANGSPUREN and has developed into one of the most successful projects of the Tyrolean festival for new music. The high standards of the Academy are vouched for by prominent figures who have acted as Composers in Residence: György Kurtág, Helmut Lachenmann, Steve Reich, Benedict Mason, Michael Gielen, Wolfgang Rihm, Martin Matalon, Johannes Maria Staud, Heinz Holliger, George Benjamin, Unsuk Chin, Hans Zender, Hans Abrahamsen, Wolfgang Mitterer, Beat Furrer, Enno Poppe, and most recently in 2017, Sofia Gubaidulina. -

Gardner • Even Orpheus Needs a Synthi Edit No Proof

James Gardner Even Orpheus Needs a Synthi Since his return to active service a few years ago1, Peter Zinovieff has appeared quite frequently in interviews in the mainstream press and online outlets2 talking not only about his recent sonic art projects but also about the work he did in the 1960s and 70s at his own pioneering computer electronic music studio in Putney. And no such interview would be complete without referring to EMS, the synthesiser company he co-founded in 1969, or namechecking the many rock celebrities who used its products, such as the VCS3 and Synthi AKS synthesisers. Before this Indian summer (he is now 82) there had been a gap of some 30 years in his compositional activity since the demise of his studio. I say ‘compositional’ activity, but in the 60s and 70s he saw himself as more animateur than composer and it is perhaps in that capacity that his unique contribution to British electronic music during those two decades is best understood. In this article I will discuss just some of the work that was done at Zinovieff’s studio during its relatively brief existence and consider two recent contributions to the documentation and contextualization of that work: Tom Hall’s chapter3 on Harrison Birtwistle’s electronic music collaborations with Zinovieff; and the double CD Electronic Calendar: The EMS Tapes,4 which presents a substantial sampling of the studio’s output between 1966 and 1979. Electronic Calendar, a handsome package to be sure, consists of two CDs and a lavishly-illustrated booklet with lengthy texts. -

Roots & Origins

Sunday 16 December 2018 7–9.15pm Tuesday 18 December 2018 7.30–9.45pm Barbican Hall LSO SEASON CONCERT ROOTS & ORIGINS Brahms Violin Concerto Interval ROMANIAN Debussy Images Enescu Romanian Rhapsody No 1 Sir Simon Rattle conductor Leonidas Kavakos violin These performances of Enescu’s Romanian Rhapsody No 1 are generously RHAPSODY supported by the Romanian Cultural Institute 16 December generously supported by LSO Friends Welcome Latest News On Our Blog We are grateful to the Romanian Cultural BRITISH COMPOSER AWARDS MARIN ALSOP ON LEONARD Institute for their generous support of these BERNSTEIN’S CANDIDE concerts. Sunday’s concert is also supported Congratulations to LSO Soundhub Associate by LSO Friends, and we are delighted to have Liam Taylor-West and LSO Panufnik Composer Marin Alsop conducted Bernstein’s Candide, so many Friends with us in the audience. Cassie Kinoshi for their success in the 2018 with the LSO earlier this month. Having We extend our thanks for their loyal and British Composer Awards. Prizes were worked closely with the composer across important support of the LSO, and their awarded to Liam for his Community Project her career, Marin drew on her unique insight presence at all our concerts. The Umbrella and to Cassie for Afronaut, into Bernstein’s music, words and sense of a jazz composition for large ensemble. theatre to tell us about the production. I wish you a very happy Christmas, and hope you can join us again in the New Year. The • lso.co.uk/more/blog elcome to this evening’s LSO LSO’s 2018/19 concert season at the Barbican FELIX MILDENBERGER JOINS THE LSO concert at the Barbican. -

Wuorinen Printable Program

The University at Buffalo Department of Music and The Robert & Carol Morris Center for 21st Century Music present Celebrating Charles Wuorinen at 80 featuring Ensemble SIGNAL Brad Lubman, conductor Tuesday, April 24, 2018 7:30pm Lippes Concert Hall in Slee Hall PROGRAM Charles Wuorinen (b. 1938) iRidule Jacqueline Leclair, oboe soloist Spin 5 Olivia De Prato, violin soloist Intermission Megalith Eric Huebner, piano soloist PERSONNEL Ensemble Signal Brad Lubman, Music Director Paul Coleman, Sound Director Olivia De Prato, Violin Lauren Radnofsky, Cello Ken Thomson, Clarinet, Bass Clarinet Adrián Sandí, Clarinet, Bass Clarinet David Friend, Piano 1 Oliver Hagen, Piano 2 Karl Larson, Piano 3 Georgia Mills, Piano 4 Matt Evans, Vibraphone, Piano Carson Moody, Marimba 1 Bill Solomon, Marimba 2 Amy Garapic, Marimba 3 Brad Lubman, Marimba Sarah Brailey, Voice 1 Mellissa Hughes, Voice 2 Kirsten Sollek, Voice 4 Charles Wuorinen In 1970 Wuorinen became the youngest composer at that time to win the Pulitzer Prize (for the electronic work Time's Encomium). The Pulitzer and the MacArthur Fellowship are just two among many awards, fellowships and other honors to have come his way. Wuorinen has written more than 260 compositions to date. His most recent works include Sudden Changes for Michael Tilson Thomas and the San Francisco Symphony, Exsultet (Praeconium Paschale) for Francisco Núñez and the Young People's Chorus of New York, a String Trio for the Goeyvaerts String Trio, and a duo for viola and percussion, Xenolith, for Lois Martin and Michael Truesdell. The premiere of of his opera on Annie Proulx's Brokeback Mountain was was a major cultural event worldwide. -

Form in the Music of John Adams

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2018 Form in the Music of John Adams Michael Ridderbusch Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Ridderbusch, Michael, "Form in the Music of John Adams" (2018). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 6503. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/6503 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Form in the Music of John Adams Michael Ridderbusch DMA Research Paper submitted to the College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Music Theory and Composition Andrew Kohn, Ph.D., Chair Travis D. Stimeling, Ph.D. Melissa Bingmann, Ph.D. Cynthia Anderson, MM Matthew Heap, Ph.D. School of Music Morgantown, West Virginia 2017 Keywords: John Adams, Minimalism, Phrygian Gates, Century Rolls, Son of Chamber Symphony, Formalism, Disunity, Moment Form, Block Form Copyright ©2017 by Michael Ridderbusch ABSTRACT Form in the Music of John Adams Michael Ridderbusch The American composer John Adams, born in 1947, has composed a large body of work that has attracted the attention of many performers and legions of listeners. -

Sir John Eliot Gardiner Les Nuits D'été

Sir John Eliot Gardiner Les nuits d’été «El llum et fa de sol i colra les pells tendres i madura les carns de les fruites que guardes.» Narcís Comadira Natura morta Programa Palau 100 DIMARTS 06.03.18 – 20.30 h Sala de Concerts London Symphony Orchestra Ann Hallenberg, mezzosoprano Sir John Eliot Gardiner, director I Part Robert Schumann (1810-1856) Obertura, scherzo i finale, op. 52 18’ Hector Berlioz (1803-1869) Les nuits d’été, op. 7 30’ Villanelle Le spectre de la rose Sur les lagunes: lamento Absence Au cimetière: clair de lune L’île inconnue II Part Robert Schumann Obertura de Genoveva, op. 81 10’ Robert Schumann Simfonia núm. 4, op. 120 (versió original de 1841) 24’ Andante con moto - Allegro di molto Romanza: Andante Scherzo: Presto Largo - Finale: Allegro vivace a l’octubre. Poc després de començar a esbossar- l’agost del 1850. De fet, les dues òperes van Schumann i Berlioz, lo, Schumann va assenyalar: “la propera simfonia sorgir en paral·lel durant el mateix període de es titularà «Clara» i la pintaré amb flautes, oboès temps. De Genoveva, només se’n varen fer tres i arpes”. De totes formes, seria un error buscar representacions. L’actitud adversa de la crítica romanticisme pur vestigis tangibles d’aquest retrat, o tractar de va fer desistir Robert Schumann de repetir mai detectar el nom de Clara amagat al teixit temàtic més una nova experiència operística. D’altra de la Simfonia, com han fet alguns crítics. La banda, Genoveva mai no ha estat popular entre primavera del 1841, tot allò que mirava o el públic, malgrat que, de tant en tant, s’ha escoltava el compositor, acabava associat a la recuperat i fins i tot enregistrat. -

October 2012

21ST CENTURY MUSIC OCTOBER 2012 INFORMATION FOR SUBSCRIBERS 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC is published monthly by 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC, P.O. Box 2842, San Anselmo, CA 94960. ISSN 1534-3219. Subscription rates in the U.S. are $96.00 per year; subscribers elsewhere should add $48.00 for postage. Single copies of the current volume and back issues are $12.00. Large back orders must be ordered by volume and be pre-paid. Please allow one month for receipt of first issue. Domestic claims for non-receipt of issues should be made within 90 days of the month of publication, overseas claims within 180 days. Thereafter, the regular back issue rate will be charged for replacement. Overseas delivery is not guaranteed. Send orders to 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC, P.O. Box 2842, San Anselmo, CA 94960. email: [email protected]. Typeset in Times New Roman. Copyright 2012 by 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC. This journal is printed on recycled paper. Copyright notice: Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC. INFORMATION FOR CONTRIBUTORS 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC invites pertinent contributions in analysis, composition, criticism, interdisciplinary studies, musicology, and performance practice; and welcomes reviews of books, concerts, music, recordings, and videos. The journal also seeks items of interest for its calendar, chronicle, comment, communications, opportunities, publications, recordings, and videos sections. Copy should be double-spaced on 8 1/2 x 11 -inch paper, with ample margins. Authors are encouraged to submit via e-mail. Prospective contributors should consult The Chicago Manual of Style, 15th ed. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003), in addition to back issues of this journal. -

06 20 PROGRAM FULL PAGE.Pdf

About the festival The New Music For Strings Festival (NMFS) is delighted to announce the launch of its second annual season from June 21 to July 1, 2017. Hosted by Stony Brook University in 2017, NMFS brings together performers and composers of contemporary classical music from across the Atlantic. NMFS showcases a roster of world-class musicians, ranging from members of the Grammy Award- winning Emerson String Quartet to faculty from Stony Brook University (NY) and Royal Academy of Music in Aarhus, Denmark. Resident faculty and artists of NMFS 2017 will be showcased alongside accomplished student participants that include graduate students from top conservatories and universities in the U.S. and Europe. The 10-day festival features fourteen events—including six concerts, three masterclasses, five lectures and a composition pre-festival workshop for high-school students. The season will culminate with a tour de force festival performance at Carnegie Hall’s Weill Recital Hall, which will highlight the full roster of 27 festival artists from America and Scandinavia. As the first festival concept of its kind in the world, NMFS seeks to explore the intersections between string playing and composition. NMFS boasts an elite artist faculty for participants to work with, many of whom have established themselves as leaders in their field in the dual role of performer-composer. By highlighting this intersectional perspective throughout the festival, NMFS offers a variety of lectures, masterclasses and concerts on the dynamic interactions between these two intertwined fields of creation and interpretation. Music has the power of bridging cultures and enlightening minds. NMFS is dedicated to sustaining and enriching the vibrant classical music community in Long Island. -

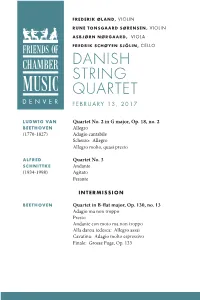

Danish String Quartet Denver February 13, 2017

FREDERIK ØLAND, VIOLIN RUNE TONSGAARD SØRENSEN, VIOLIN ASBJØRN NØRGAARD, VIOLA FREDRIK SCHØYEN SJÖLIN, CELLO DANISH STRING QUARTET DENVER FEBRUARY 13, 2017 LUDWIG VAN Quartet No. 2 in G major, Op. 18, no. 2 BEETHOVEN Allegro (1770-1827) Adagio cantabile Scherzo: Allegro Allegro molto, quasi presto ALFRED Quartet No. 3 SCHNITTKE Andante (1934-1998) Agitato Pesante INTERMISSION BEETHOVEN Quartet in B-flat major, Op. 130, no. 13 Adagio ma non troppo Presto Andante con moto ma non troppo Alla danza tedesca: Allegro assai Cavatina: Adagio molto espressivo Finale: Grosse Fuge, Op. 133 FREDERIK ØLAND DANISH STRING QUARTET violin RUNE TONSGAARD Embodying the quintessential elements of a fine chamber SØRENSEN music ensemble, the Danish String Quartet has established violin a reputation for their integrated sound, impeccable ASBJØRN NØRGAARD intonation, and judicious balance. Since making their debut viola in 2002 at the Copenhagen Festival, the musical friends have demonstrated a passion for Scandinavian composers, FREDRIK SCHØYEN who they frequently incorporate into adventurous SJÖLIN contemporary programs, while also giving skilled and cello profound interpretations of the classical masters. The New York Times selected the quartet’s concerts as highlights of the season during their Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center Two Residency, and in February 2016 they received the Borletti Buitoni Trust provided to support outstanding young artists in their international endeavors, joining an illustrious roster of past recipients. The Danish String Quartet’s 2016-2017 season includes debuts at the Edinburgh Festival and Zankel Hall at Carnegie Hall. In addition to over thirty North American engagements, the quartet’s robust international schedule takes them to their home country, Denmark, as well as throughout Germany, Austria, the United Kingdom, Poland, Israel, as well as Argentina, Peru, and Colombia. -

Juilliard Percussion Ensemble Daniel Druckman , Director Daniel Parker and Christopher Staknys , Piano Zlatomir Fung , Cello

Monday Evening, December 11, 2017, at 7:30 The Juilliard School presents Juilliard Percussion Ensemble Daniel Druckman , Director Daniel Parker and Christopher Staknys , Piano Zlatomir Fung , Cello Bell and Drum: Percussion Music From China GUO WENJING (b. 1956) Parade (2003) SAE HASHIMOTO EVAN SADDLER DAVID YOON ZHOU LONG (b. 1953) Wu Ji (2006) CHRISTOPHER STAKNYS, Piano BENJAMIN CORNOVACA LEO SIMON LEI LIANG (b. 1972) Inkscape (2014) DANIEL PARKER, Piano TYLER CUNNINGHAM JAKE DARNELL OMAR EL-ABIDIN EUIJIN JUNG Intermission The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment are not permitted in this auditorium. Information regarding gifts to the school may be obtained from the Juilliard School Development Office, 60 Lincoln Center Plaza, New York, NY 10023-6588; (212) 799-5000, ext. 278 (juilliard.edu/giving). Alice Tully Hall Please make certain that all electronic devices are turned off during the performance. CHOU WEN-CHUNG (b. 1923) Echoes From the Gorge (1989) Prelude: Exploring the modes Raindrops on Bamboo Leaves Echoes From the Gorge, Resonant and Free Autumn Pond Clear Moon Shadows in the Ravine Old Tree by the Cold Spring Sonorous Stones Droplets Down the Rocks Drifting Clouds Rolling Pearls Peaks and Cascades Falling Rocks and Flying Spray JOSEPH BRICKER TAYLOR HAMPTON HARRISON HONOR JOHN MARTIN THENELL TAN DUN (b. 1957) Elegy: Snow in June (1991) ZLATOMIR FUNG, Cello OMAR EL-ABIDIN BENJAMIN CORNOVACA TOBY GRACE LEO SIMON Performance time: Approximately 1 hour and 45 minutes, including one intermission Notes on the Program Scored for six Beijing opera gongs laid flat on a table, Parade is an exhilarating work by Jay Goodwin that amazes both with its sheer difficulty to perform and with the incredible array of dif - “In studying non-Western music, one ferent sounds that can be coaxed from must consider the character and tradition what would seem to be a monochromatic of its culture as well as all the inherent selection of instruments. -

Wiebe, Confronting Opera

King’s Research Portal DOI: 10.1080/02690403.2017.1286132 Document Version Peer reviewed version Link to publication record in King's Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Wiebe, H. (2020). Confronting Opera in the 1960s: Birtwistle’s Punch and Judy. Journal of the Royal Musical Association , 142(1), 173-204. https://doi.org/10.1080/02690403.2017.1286132 Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on King's Research Portal is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Post-Print version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version for pagination, volume/issue, and date of publication details. And where the final published version is provided on the Research Portal, if citing you are again advised to check the publisher's website for any subsequent corrections. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognize and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. •Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. •You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain •You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the Research Portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim.