Edited and with an Introduction by Olivia Carter Mather and J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

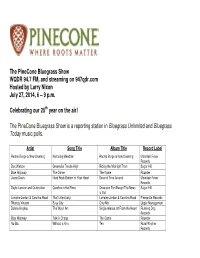

The Pinecone Bluegrass Show WQDR 94.7 FM, and Streaming on 947Qdr.Com Hosted by Larry Nixon July 27, 2014, 6 – 9 P.M

The PineCone Bluegrass Show WQDR 94.7 FM, and streaming on 947qdr.com Hosted by Larry Nixon July 27, 2014, 6 – 9 p.m. Celebrating our 25 th year on the air! The PineCone Bluegrass Show is a reporting station in Bluegrass Unlimited and Bluegrass Today music polls. Artist Song Title Album Title Record Label Rachel Burge & New Dawning Kentucky Mandolin Rachel Burge & New Dawning Mountain Fever Records Doc Watson Greenville Trestle High Riding the Midnight Train Sugar Hill Blue Highway The Game The Game Rounder Jason Davis Hard Rock Bottom of Your Heart Second Time Around Mountain Fever Records Doyle Lawson and Quicksilver Carolina in the Pines Once and For Always/The News Sugar Hill is Out Lorraine Jordan & Carolina Road That’s Kentucky Lorraine Jordan & Carolina Road Pinecastle Records Rhonda Vincent Busy City Only Me Upper Management Donna Hughes The Way I Am Single release off From the Heart Running Dog Records Blue Highway Talk is Cheap The Game Rounder Nu-Blu Without a Kiss Ten Rural Rhythm Records Kruger Brothers Streamlined Cannonball Remembering Doc Watson Double Time Music The Seldom Scene With Body and Soul The Best of The Seldom Scene Rebel Records Darrell Webb Band Folks Like Us Dream Big Mountain Fever Records Seldom Scene Wait a Minute (feat. John Starling) Long Time… Seldom Scene Smithsonian/Folkwa ys Becky Buller Southern Flavor ’Tween Earth & Sky Dark Shadow Recording Sideline Girl at the Crossroads Bar Session I Mountain Fever Records Dolly Parton Blue Smoke Blue Smoke Sony Masterworks The Gentlemen of Bluegrass Carolina Memories Carolina Memories Pinecastle Records Richard Bennett Wayfaring Stranger (feat. -

Various Lonesome Valley (A Collection of American Folk Music) Mp3, Flac, Wma

Various Lonesome Valley (A Collection Of American Folk Music) mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Folk, World, & Country Album: Lonesome Valley (A Collection Of American Folk Music) Country: US Released: 2006 Style: Country, Folk MP3 version RAR size: 1863 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1640 mb WMA version RAR size: 1961 mb Rating: 4.3 Votes: 913 Other Formats: ASF MIDI XM AIFF AUD APE AC3 Tracklist 1 –Pete Seeger, Bess Lomax, Tom Glazer Down In The Valley 2:35 2 –Cisco Houston The Rambler 3:18 3 –Butch Hawes Arthritis Blues 3:23 4 –Pete Seeger, Bess Lomax, Tom Glazer Polly Wolly Doodle 1:55 5 –Lee Hays, Pete Seeger, Bess Lomax Lonesome Traveler 1:55 6 –Cisco Houston On Top Of Old Smoky 1:35 7 –Pete Seeger Black Eyed Suzie 2:12 8 –Woody Guthrie Cowboy Waltz 2:06 9 –Cisco Houston and Woody Guthrie Sowing On The Mountain 2:29 Companies, etc. Copyright (c) – Folkways Records & Service Corp. Copyright (c) – Smithsonian Folkways Recordings Phonographic Copyright (p) – Smithsonian Folkways Recordings Credits Artwork – Carlis* Notes Professionally printed CDr on-demand reissue of the 1950/1958 10'' release on Folkways Records. The enhanced CDr includes a PDF file of the booklet included with the original release. © 1950 Folkways Records & Service Corp. ℗ © 2006 Smithsonian Folkways Recordings Total time: 21 min. Gatefold cardboard sleeve. Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode (Scanned): 093070201026 Label Code: LC 9628 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year FP 10 Various Lonesome Valley (10") Folkways Records FP 10 US 1951 FA 2010 Various Lonesome Valley (10") Folkways Records FA 2010 US 1958 FP 10 Various Lonesome Valley (10") Folkways Records FP 10 US 1951 Related Music albums to Lonesome Valley (A Collection Of American Folk Music) by Various Pete Seeger - Birds, Beasts, Bugs and Little Fishes Pete Seeger And Frank Hamilton - Nonesuch And Other Folk Tunes Lead Belly - Shout On (Lead Belly Legacy Vol. -

Flatpicking Guitar Magazine Index of Reviews

Flatpicking Guitar Magazine Index of Reviews All reviews of flatpicking CDs, DVDs, Videos, Books, Guitar Gear and Accessories, Guitars, and books that have appeared in Flatpicking Guitar Magazine are shown in this index. CDs (Listed Alphabetically by artists last name - except for European Gypsy Jazz CD reviews, which can all be found in Volume 6, Number 3, starting on page 72): Brandon Adams, Hardest Kind of Memories, Volume 12, Number 3, page 68 Dale Adkins (with Tacoma), Out of the Blue, Volume 1, Number 2, page 59 Dale Adkins (with Front Line), Mansions of Kings, Volume 7, Number 2, page 80 Steve Alexander, Acoustic Flatpick Guitar, Volume 12, Number 4, page 69 Travis Alltop, Two Different Worlds, Volume 3, Number 2, page 61 Matthew Arcara, Matthew Arcara, Volume 7, Number 2, page 74 Jef Autry, Bluegrass ‘98, Volume 2, Number 6, page 63 Jeff Autry, Foothills, Volume 3, Number 4, page 65 Butch Baldassari, New Classics for Bluegrass Mandolin, Volume 3, Number 3, page 67 William Bay: Acoustic Guitar Portraits, Volume 15, Number 6, page 65 Richard Bennett, Walking Down the Line, Volume 2, Number 2, page 58 Richard Bennett, A Long Lonesome Time, Volume 3, Number 2, page 64 Richard Bennett (with Auldridge and Gaudreau), This Old Town, Volume 4, Number 4, page 70 Richard Bennett (with Auldridge and Gaudreau), Blue Lonesome Wind, Volume 5, Number 6, page 75 Gonzalo Bergara, Portena Soledad, Volume 13, Number 2, page 67 Greg Blake with Jeff Scroggins & Colorado, Volume 17, Number 2, page 58 Norman Blake (with Tut Taylor), Flatpickin’ in the -

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs No. Interpret Title Year of release 1. Bob Dylan Like a Rolling Stone 1961 2. The Rolling Stones Satisfaction 1965 3. John Lennon Imagine 1971 4. Marvin Gaye What’s Going on 1971 5. Aretha Franklin Respect 1967 6. The Beach Boys Good Vibrations 1966 7. Chuck Berry Johnny B. Goode 1958 8. The Beatles Hey Jude 1968 9. Nirvana Smells Like Teen Spirit 1991 10. Ray Charles What'd I Say (part 1&2) 1959 11. The Who My Generation 1965 12. Sam Cooke A Change is Gonna Come 1964 13. The Beatles Yesterday 1965 14. Bob Dylan Blowin' in the Wind 1963 15. The Clash London Calling 1980 16. The Beatles I Want zo Hold Your Hand 1963 17. Jimmy Hendrix Purple Haze 1967 18. Chuck Berry Maybellene 1955 19. Elvis Presley Hound Dog 1956 20. The Beatles Let It Be 1970 21. Bruce Springsteen Born to Run 1975 22. The Ronettes Be My Baby 1963 23. The Beatles In my Life 1965 24. The Impressions People Get Ready 1965 25. The Beach Boys God Only Knows 1966 26. The Beatles A day in a life 1967 27. Derek and the Dominos Layla 1970 28. Otis Redding Sitting on the Dock of the Bay 1968 29. The Beatles Help 1965 30. Johnny Cash I Walk the Line 1956 31. Led Zeppelin Stairway to Heaven 1971 32. The Rolling Stones Sympathy for the Devil 1968 33. Tina Turner River Deep - Mountain High 1966 34. The Righteous Brothers You've Lost that Lovin' Feelin' 1964 35. -

Music for the People: the Folk Music Revival

MUSIC FOR THE PEOPLE: THE FOLK MUSIC REVIVAL AND AMERICAN IDENTITY, 1930-1970 By Rachel Clare Donaldson Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in History May, 2011 Nashville, Tennessee Approved Professor Gary Gerstle Professor Sarah Igo Professor David Carlton Professor Larry Isaac Professor Ronald D. Cohen Copyright© 2011 by Rachel Clare Donaldson All Rights Reserved For Mary, Laura, Gertrude, Elizabeth And Domenica ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would not have been able to complete this dissertation had not been for the support of many people. Historians David Carlton, Thomas Schwartz, William Caferro, and Yoshikuni Igarashi have helped me to grow academically since my first year of graduate school. From the beginning of my research through the final edits, Katherine Crawford and Sarah Igo have provided constant intellectual and professional support. Gary Gerstle has guided every stage of this project; the time and effort he devoted to reading and editing numerous drafts and his encouragement has made the project what it is today. Through his work and friendship, Ronald Cohen has been an inspiration. The intellectual and emotional help that he provided over dinners, phone calls, and email exchanges have been invaluable. I greatly appreciate Larry Isaac and Holly McCammon for their help with the sociological work in this project. I also thank Jane Anderson, Brenda Hummel, and Heidi Welch for all their help and patience over the years. I thank the staffs at the Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage, the Kentucky Library and Museum, the Archives at the University of Indiana, and the American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress (particularly Todd Harvey) for their research assistance. -

The Ballads of the Southern Mountains and the Escape from Old Europe

B AR B ARA C HING Happily Ever After in the Marketplace: The Ballads of the Southern Mountains and the Escape from Old Europe Between 1882 and 1898, Harvard English Professor Francis J. Child published The English and Scottish Popular Ballads, a five volume col- lection of ballad lyrics that he believed to pre-date the printing press. While ballad collections had been published before, the scope and pur- ported antiquity of Child’s project captured the public imagination; within a decade, folklorists and amateur folk song collectors excitedly reported finding versions of the ballads in the Appalachians. Many enthused about the ‘purity’ of their discoveries – due to the supposed isolation of the British immigrants from the corrupting influences of modernization. When Englishman Cecil Sharp visited the mountains in search of English ballads, he described the people he encountered as “just English peasant folk [who] do not seem to me to have taken on any distinctive American traits” (cited in Whisnant 116). Even during the mid-century folk revival, Kentuckian Jean Thomas, founder of the American Folk Song Festival, wrote in the liner notes to a 1960 Folk- ways album featuring highlights from the festival that at the close of the Elizabethan era, English, Scotch, and Scotch Irish wearied of the tyranny of their kings and spurred by undaunted courage and love of inde- pendence they braved the perils of uncharted seas to seek freedom in a new world. Some tarried in the colonies but the braver, bolder, more venturesome of spirit pressed deep into the Appalachians bringing with them – hope in their hearts, song on their lips – the song their Anglo-Saxon forbears had gathered from the wander- ing minstrels of Shakespeare’s time. -

Creating a Roadmap for the Future of Music at the Smithsonian

Creating a Roadmap for the Future of Music at the Smithsonian A summary of the main discussion points generated at a two-day conference organized by the Smithsonian Music group, a pan- Institutional committee, with the support of Grand Challenges Consortia Level One funding June 2012 Produced by the Office of Policy and Analysis (OP&A) Contents Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................................. 3 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................ 4 Background ............................................................................................................................................ 4 Conference Participants ..................................................................................................................... 5 Report Structure and Other Conference Records ............................................................................ 7 Key Takeaway ........................................................................................................................................... 8 Smithsonian Music: Locus of Leadership and an Integrated Approach .............................. 8 Conference Proceedings ...................................................................................................................... 10 Remarks from SI Leadership ........................................................................................................ -

JANE LEE HOOKER Twitter.Com/Janeleehooker Jane Lee Hooker Is a Band of five Women from New York City Who Take Traditional Blues on a Fast and Rough Ride

917-843-5943 Alan Rand 2014 janeleehooker.com photo by facebook.com/JaneLeeHooker janeleehooker.bandcamp.com JANE LEE HOOKER twitter.com/JaneLeeHooker Jane Lee Hooker is a band of five women from New York City who take traditional blues on a fast and rough ride. Their self-released debut, “No B!,” was released in November. Notable stages they’ve graced include Pappy & Harriet’s [email protected] (Pioneertown, CA), Dogfish Head Brewery (Rehoboth Beach, DE), the Harrisburg Midtown Arts Center (Harrisburg, PA), Ojai Deer Lodge (Ojai, CA), and the Wonderbar (Asbury Park, NJ). Back home in NYC, they can be seen at the Knitting Factory, Mercury Lounge, Bitter End and Rock Shop, among other places. The band’s calling cards are songs by Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Johnny Winter, Big Mama Thornton, and other blues greats—all fed through double lead guitars, a heavy rhythm section, and soul-scouring vocals. These women are by no means new to the game. Between the five band members, they have decades of experience playing, recording and touring both nationally and internationally. Individually, the members of Jane Lee Hooker have played for thousands of fans while sharing bills with the likes of Motorhead, MC5, Lynyrd Skynyrd, and Deep Purple, among others. And they’ve played more club gigs in more cities than even they can believe. So how’d this gang of pros finally find each other? Guitarists Hightop and Tina honed their mutual love of blazing dual leads during their time together in Helldorado in the 90s. From there, Hightop joined Nashville Pussy, Tina joined Bad Wizard, and both women toured the world. -

American Old-Time Musics, Heritage, Place A

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO SOUNDS OF THE MODERN BACKWOODS: AMERICAN OLD-TIME MUSICS, HERITAGE, PLACE A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC BY LAURA C.O. SHEARING CHICAGO, ILLINOIS JUNE 2020 ã Copyright 2020 Laura C.O. Shearing All rights reserved. ––For Henrietta Adeline, my wildwood flower Table of Contents List of Figures .............................................................................................................................. v List of Tables .............................................................................................................................. vi Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................... vii Abstract ...................................................................................................................................... ix Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 1 1. Contextualizing Old-Time ..................................................................................................... 22 2. The Making of an Old-Time Heritage Epicenter in Surry County, North Carolina ................... 66 3. Musical Trail-Making in Southern Appalachia ....................................................................... 119 4. American Old-Time in the British Isles ................................................................................ -

“Jewish Problem”: Othering the Jews and Homogenizing Europe

NOTES Introduction 1. Dominick LaCapra, History and Memory after Auschwitz (Ithaca, NY; London: Cornell University Press, 1998), 26. 2. Lyotard, Jean Francois, Heidegger and “the jews,” trans. Andreas Michel and Mark S. Roberts (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1990). 3. Kathy Acker, Empire of the Senseless (New York: Grove Press, 1988). 4. Charles Maier, The Unmasterable Past, History, Holocaust and German National Identity (Harvard University Press, 1988), 1. 5. See Maurizio Passerin d’Entrèves and Seyla Benhabib, eds., Habermas and the Unfinished Project of Modernity (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, 1996). 6. LaCapra, History and Memory after Auschwitz, 22, note 14. 7. Ibid., 41. 8. Ibid., 40–41. 9. Jeffrey Alexander et al., Cultural Trauma and Collective Identity (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004). 10. Idith Zertal, Israel’s Holocaust and the Politics of Nationhood, trans. Chaya Galai, Cambridge Middle East Studies 21 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005), 4. 11. Angi Buettner, “Animal Holocausts,” Cultural Studies Review 8.1 (2002): 28. 12. Angi Buettner, Haunted Images: The Aesthetics of Catastrophe in a Post-Holocaust World (PhD diss., University of Queensland, 2005), 139. 13. Ibid, 139. 14. Ibid., 157. 15. Ibid., 159–160. 16. Ibid., 219. 17. Tim Cole, Selling the Holocaust: From Auschwitz to Schindler, How History Is Bought, Packaged and Sold (New York: Routledge, 1999). 18. LaCapra, History and Memory after Auschwitz, 21. Chapter One Producing the “Jewish Problem”: Othering the Jews and Homogenizing Europe 1. Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi, “Exile and Expulsion in Jewish History,” in Crisis and Creativity in the Sephardic World 1391–1648, ed. -

Woody Guthrie's Angry Sons and Daughters

“Seeds Blowin’ Up the Highway in the South Wind”: Woody Guthrie’s Angry Sons and Daughters Roxanne Harde University of Alberta, Augustana1 Abstract Both anger and hope drive Woody Guthrie’s protest songs. Lyrics like “This Land Is Your Land” offer a hopefully angry voice that continues to be heard in the work of contemporary American singer-songwriters. This essay analyzes the ways in which Guthrie’s voice and vision continue to inform the songs of Bruce Springsteen, Steve Earle, Patty Griffin, Gillian Welch and David Rawlings, and Mary Gauthier. By bringing Guthrie’s hopeful anger that insists on justice and mercy and precludes sentimentality, hostility, and nihilism into conversation with the artists who continue his legacy of activism, this paper looks to the “Seeds” Guthrie sowed. In November 2009, at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame 25th Anniversary Concert, Bruce Springsteen opened his set with an astute and angry commentary and then introduced the perpetually enraged Tom Morello before launching into a blistering version of “The Ghost of Tom Joad,” just one of many Springsteen songs that depend upon the work of Woody Guthrie. “If you pick up the newspaper, you see millions of people out of work; you see a blood fight over decent health care for our citizens, and you see people struggling to hold on to their homes,” Springsteen said: “If Woody Guthrie were alive today, he’d have a lot to write about: high times on Wall Street and hard times on Main Street.” Relatedly, when David Rawlings performs “I Hear Them All,” with or without 1 Copyright © Roxanne Harde, 2018. -

November 2009 Newsletter

November 09 Newsletter ------------------------------ Yesterday & Today Records PO Box 54 Miranda NSW 2228 Phone/fax: (02)95311710 Email:[email protected] Web: www.yesterdayandtoday.com.au ------------------------------------------------ Postage: 1cd $2/ 2cds 3-4 cds $6.50 ------------------------------------------------ Loudon Wainwright III “High Wide & Handsome – The Charlie Poole Project” 2cds $35. If you have any passion at all for bluegrass or old timey music then this will be (hands down) your album of the year. Loudon Wainwright is an artist I have long admired since I heard a song called “Samson and the Warden” (a wonderfully witty tale of a guy who doesn’t mind being in gaol so long as the warden doesn’t cut his hair) on an ABC radio show called “Room to Move” many years ago. A few years later he had his one and only “hit” with the novelty “Dead Skunk”. Now Loudon pundits will compare the instrumentation on this album with that on that song, and if a real pundit with that of his “The Swimming Song”. The backing is restrained. Banjo (Poole’s own instrument of choice), with guitar, some great mandolin (from Chris Thile) some fiddle (multi instrumentalist David Mansfield), some piano and harmonica and on a couple of tracks some horns. Now, Charlie Poole to the uninitiated was a major star in the very early days of country music. He is said to have pursued a musical career so he wouldn’t have to work and at the same time he could ensure his primary source of income, bootleg liquor, was properly distilled. He was no writer and adapted songs he had heard to his style.