American Old-Time Musics, Heritage, Place A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FACULTY Fl FAMOUS

U.S. POSTAGE BULK RATE zoz<z$ I ft '993fHBMTTW PAID °^yi *a ^t8T PERMIT NO. 33 uomxS uopaoo Port Washington, Wis. FBI DOCUMENTS, pg. 3 + WAYSIDE INN CLOSED, pg. 2 + MANGELSDORFF ON CONCERTS, pg. 7 I THE FAMOUS REVOLUTIONARIES SCHOOL Are you one of the angry ones who bangs his nead against the wall while all your friends talk about "peace and love" and "reforming the system"? Then why not send away for our simple aptitude test and see if you might not have the potential to become a real revolutionary. FAMOUS REVOLUTIONARIES SCHOOL | the only correspondance school of revolution actually taught by real revolutionaries. You'll receive personal attention in your attempts to off the pig and relate through Marxist-Leninist dialectics to the oppreseed masses. Write in today. If you are one of the first 500 people to answer this ad, you'll receive a free AK-47 and 2000 rounds of ammunition. SAMPLE QUESTIONS FROM THE FAMOUS REVOLUTIONARIES SCHOOL APTITUDE TEST: Fill in the blanks: Multiple choise: a 1. "Right, The chairman of the standing committee of the Chinese People's 2. "Ho, Ho, Ho Chi Mihn/ NLF will surely" Jj|§ Communist Party is; « 1. Blaze Starr | 2. Gregory Peck 3."1 ... 2 ... 3 ... 4.../ 3. Tina Turner II We don't want your fucking 4. All of the above FACULTY fL Enver Hoxha Alexander Karenskv Kin Agnew Mario Savio Charles Manson Maharishi Mahesh Yogi Nikita Khrushchev Adam Clayton Powell Tim Leary Vance Packard Bo Bolinski Amelia Earhart William Burroughs John Dos Passos &u FAMOUS REVOLUTIONARIES SCHOOL 233 E. -

A Film by Chris Hegedus and D a Pennebaker

a film by Chris Hegedus and D A Pennebaker 84 minutes, 2010 National Media Contact Julia Pacetti JMP Verdant Communications [email protected] (917) 584-7846 FIRST RUN FEATURES The Film Center Building, 630 Ninth Ave. #1213 New York, NY 10036 (212) 243-0600 Fax (212) 989-7649 Website: www.firstrunfeatures.com Email: [email protected] PRAISE FOR KINGS OF PASTRY “The film builds in interest and intrigue as it goes along…You’ll be surprised by how devastating the collapse of a chocolate tower can be.” –Mike Hale, The New York Times Critic’s Pick! “Alluring, irresistible…Everything these men make…looks so mouth-watering that no one should dare watch this film on even a half-empty stomach.” – Kenneth Turan, Los Angeles Times “As the helmers observe the mental, physical and emotional toll the competition exacts on the contestants and their families, the film becomes gripping, even for non-foodies…As their calm camera glides over the chefs' almost-too-beautiful-to-eat creations, viewers share their awe.” – Alissa Simon, Variety “How sweet it is!...Call it the ultimate sugar high.” – VA Musetto, The New York Post “Gripping” – Jay Weston, The Huffington Post “Chris Hegedus and D.A. Pennebaker turn to the highest levels of professional cooking in Kings of Pastry,” a short work whose drama plays like a higher-stakes version of popular cuisine-oriented reality TV shows.” – John DeFore, The Hollywood Reporter “A delectable new documentary…spellbinding demonstrations of pastry-making brilliance, high drama and even light moments of humor.” – Monica Eng, The Chicago Tribune “More substantial than any TV food show…the antidote to Gordon Ramsay.” – Andrea Gronvall, Chicago Reader “This doc is a demonstration that the basics, when done by masters, can be very tasty.” - Hank Sartin, Time Out Chicago “Chris Hegedus and D.A. -

Rocky Mountain Old-Time Music Festival July 10-13, 2014

Rocky Mountain Old-time Music Festival July 10-13, 2014 Final Schedule Thursday, July 10th Gate Open: 12:00pm – 9:00pm Contest Registration: 12:00pm – 9:00pm (Gate) Festival Kick-off (Event Center Lawn) 5:30pm Potluck Dinner 6:30pm Pie Contest Concert (Stage) 7:00pm– 8:00pm Soda Rock Ramblers (Larry Edelman, David Cahn, Linda Askew and Scott Mathis) Square Dance (Event Center Dance Hall) 8:30pm–11:00pm Band: Ozark Flyer (Liz Amos, Amber Gaddy, David Cavins) Caller: Chris Kermiet Friday, July 11th Gate Open: 9:00am – 9:00pm Contest Registration: 12:00pm – 3:15pm (Gate) Workshops 9:30am – 11:00am *Beginning Clawhammer Banjo – Smith Koester (Event Center Dance Hall) *Guitar Backup: Missouri “Rules” and more – Andy Gribble (Gathering Place) *Fiddle Music of Tommy Jarrell – Brad Leftwich (Event Center Tent) 11:15am – 12:45pm *Beginning Fiddle – Genevieve Koester (Gathering Place) *Round Peak Banjo and Beyond – Tom Sauber (Event Center Tent *Square Dance Caller’s Workshop – Larry Edelman (Event Center Dance Hall) 1:00pm – 2:30pm *Old-time Vocals: Devil in the Details – Alice Gerrard (Event Center Dance Hall) *Banjo: Intermediate Tunes and Techniques – Dave Landreth (Gathering Place) *Ozarks Dance Music of Bob Holt – Ozark Flyer (Event Center Tent) 2:45pm – 4:15pm *Tunes of the Southwest – Soda Rock Ramblers (Event Center Dance Hall) Contest Prelims (Stage) 3:30pm – 6:30pm Concert (Stage) 7:00 – 8:00pm White Mule (Genevieve Koester, Smith Koester, Andy Gribble) Square Dance (Event Center Dance Hall) 8:30 – 11:00pm Band: Tom, Brad, and Alice -

Free Land Attracted Many Colonists to Texas in 1840S 3-29-92 “No Quitting Sense” We Claim Is Typically Texas

“Between the Creeks” Gwen Pettit This is a compilation of weekly newspaper columns on local history written by Gwen Pettit during 1986-1992 for the Allen Leader and the Allen American in Allen, Texas. Most of these articles were initially written and published, then run again later with changes and additions made. I compiled these articles from the Allen American on microfilm at the Allen Public Library and from the Allen Leader newspapers provided by Mike Williams. Then, I typed them into the computer and indexed them in 2006-07. Lois Curtis and then Rick Mann, Managing Editor of the Allen American gave permission for them to be reprinted on April 30, 2007, [email protected]. Please, contact me to obtain a free copy on a CD. I have given a copy of this to the Allen Public Library, the Harrington Library in Plano, the McKinney Library, the Allen Independent School District and the Lovejoy School District. Tom Keener of the Allen Heritage Guild has better copies of all these photographs and is currently working on an Allen history book. Keener offices at the Allen Public Library. Gwen was a longtime Allen resident with an avid interest in this area’s history. Some of her sources were: Pioneering in North Texas by Capt. Roy and Helen Hall, The History of Collin County by Stambaugh & Stambaugh, The Brown Papers by George Pearis Brown, The Peters Colony of Texas by Seymour V. Conner, Collin County census & tax records and verbal history from local long-time residents of the county. She does not document all of her sources. -

1 a Conversation with Abigail Washburn by Frank

A Conversation with Abigail Washburn by Frank Goodman (9/2005, Puremusic.com) It’s curious in the arts, especially music, that success or notoriety can sometimes come more easily to those who started late, or never even planned to be an artist in the first place. But perhaps, by the time that music seriously enters their life, people they’ve met or other things that they’ve done or been interact with that late-breaking musical urge and catalytically convert it into something that works, takes shape or even wings. And so many who may have played the same instrument or sung or composed the same style of music all their lives may never have been rewarded, or at least noticed, for a life’s work. Timing, including the totality of what one brings to the table at that particular time, seems to be what matters. Or destiny, perhaps, if one believes in such a thing. By the time that musical destiny came knocking at Abigail Washburn’s door, her young life was already paved with diverse experiences. She’d gone abroad to China in her freshman year at college, and it changed her fundamentally. She became so interested in that culture and that tradition that it blossomed into a similar interest in her own culture when she returned, and she went deeply into the music of Doc Watson and other mountain music figures, into old time and clawhammer banjo music in particular. She’d sung extensively in choral groups already, so that came naturally. She was working as a lobbyist and living in Vermont, and had close friends who were a string band. -

Kraut Creek Ramblers

Appalachian State University’s Office of Arts and Cultural Programs presents 2019-2020 Season K-12 Performing Arts Series October 23, 2019 Kraut Creek Ramblers School Bus As an integral part of the Performing Arts Series, APPlause! matinées offer a variety of performances at venues across the Appalachian State University campus that feature university-based artists as well as local, regional and world-renowned professional artists. These affordable performances offer access to a wide variety of art disciplines for K-12 students. The series also offers the opportunity for students from the Reich College of Education to view a field trip in action without having to leave campus. Among the 2019-2020 series performers, you will find those who will also be featured in the Performing Arts Series along with professional artists chosen specifically for our student audience as well as performances by campus groups. Before the performance... Familiarize your students with what it means to be a great audience member by introducing these theatre etiquette basics: • Arrive early enough to find your seats and settle in before the show begins (20- 30 minutes). • Remember to turn your electronic devices OFF so they do not disturb the performers or other audience members. • Remember to sit appropriately and to stay quiet so that the audience members around you can enjoy the show too. PLEASE NOTE: *THIS EVENT IS SCHEDULED TO LAST APPROX 60 MINUTES. 10:00am – 11:00am • Audience members arriving by car should plan to park in the Rivers Street Parking Deck. There is a small charge for parking. Buses should plan to park along Rivers Street – Please indicate to the Parking and Traffic Officer when you plan to move your bus (i.e. -

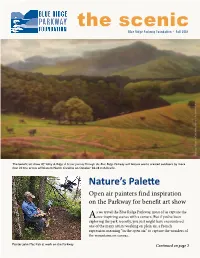

2018 Fall Issue of the Scenic

the scenic Blue Ridge Parkway Foundation - Fall 2018 Painting “Moses H. Cone Memorial Park” by John Mac Kah John Cone Memorial Park” by “Moses H. Painting The benefit art show Of Valley & Ridge: A Scenic Journey Through the Blue Ridge Parkway will feature works created outdoors by more than 20 fine artists of Western North Carolina on October 26-28 in Asheville. Nature’s Palette Open air painters find inspiration on the Parkway for benefit art show s we travel the Blue Ridge Parkway, most of us capture the Aawe-inspiring scenes with a camera. But if you’ve been exploring the park recently, you just might have encountered one of the many artists working en plein air, a French expression meaning “in the open air,” to capture the wonders of the mountains on canvas. Painter John Mac Kah at work on the Parkway Continued on page 2 Continued from page 1 Sitting in front of small easels with brushes and paint-smeared palettes in hand, these artists leave the walls of the studio behind to experience painting amid the landscape and fresh air. The Saints of Paint and Blue Ridge Parkway Foundation are inviting guests on a visual adventure with the benefit art show, Of Valley & Ridge: A Scenic Journey Through the Blue Ridge Parkway, showcasing the works of Western North Carolina fine artists from October 26 to 28 at Zealandia castle in Asheville, North Carolina. The show opens with a ticketed gala from 5 to 8 p.m., Friday, October 26, at the historical Tudor mansion, Zealandia, atop Beaucatcher Mountain. -

Clawhammer Illuminations What Would THESE Guys Do? Five High-Profile Progressive Clawhammer Artists Answer

Clawhammer Illuminations What would THESE guys do? Five high-profile progressive clawhammer artists answer common questions concerning the banjo Clawhammer Illuminations What would THESE guys do? Five high-profile progressive clawhammer artists answer common questions concerning the banjo Online banjo forums are filled with all sorts of questions from players interested in instrument choices, banjo set up, personal playing styles, technique, etc. As valuable as these forums might be, they can also be confusing for players trying to navigate advice posted from banjoists who's playing experience might range from a few weeks to literally decades. It was these forum discussions that started me thinking about how nice it would to have access to a collection of banjo related questions that were answered by some of the most respected "progressive" clawhammer banjoists performing today. I am very excited about this project as I don't believe any comprehensive collection of this nature has been published before… Mike Iverson 1 © 2013 by Mikel D. Iverson Background Information: Can you describe what it is about your personal style of play that sets you apart from other clawhammer banjoists? What recording have you made that best showcases this difference? Michael Miles: As musicians, I believe we are the sum of what he have heard. So the more you listen, the richer you get. My personal musical style on the banjo is in great part rooted in Doc Watson and JS Bach. Through Doc Watson, I learned about the phrasing of traditional music. Through Bach, I learned the majesty and reach of all music. -

Ruination Day”

Woody Guthrie Annual, 4 (2018): Fernandez, “Ruination Day” “Ruination Day”: Gillian Welch, Woody Guthrie, and Disaster Balladry1 Mark F. Fernandez Disasters make great art. In Gillian Welch’s brilliant song cycle, “April the 14th (Part 1)” and “Ruination Day,” the Americana songwriter weaves together three historical disasters with the “tragedy” of a poorly attended punk rock concert. The assassination of Abraham Lincoln in 1865, the sinking of the Titanic in 1912, and the epic dust storm that took place on what Americans call “Black Sunday” in 1935 all serve as a backdrop to Welch’s ballad, which also revolves around the real scene of a failed punk show that she and musical partner David Rawlings had encountered on one of their earlier tours. The historical disasters in question all coincidentally occurred on the fourteenth day of April. Perhaps even more important, the history of Welch’s “Ruination Day” reveals the important relationship between history and art as well as the enduring relevance of Woody Guthrie’s influence on American songwriting.2 Welch’s ouevre, like Guthrie’s, often nods to history. From the very instruments that she and Rawlings play to the themes in her original songs to the tunes she covers, she displays a keen awareness and reverence for the past. The sonic quality of her recordings, along with her singing and musical style, also echo the past. This historical quality is quite deliberate. Welch and Rawlings play vintage instruments to achieve much of that sound. Welch’s axes are all antiques—her main guitar is a 1956 Gibson J-50. -

Old Time Banjo

|--Compilations | |--Banjer Days | | |--01 Rippling Waters | | |--02 Johnny Don't Get Drunk | | |--03 Hand Me down My Old Suitcase | | |--04 Moonshiner | | |--05 Pass Around the Bottle | | |--06 Florida Blues | | |--07 Cuckoo | | |--08 Dixie Darling | | |--09 I Need a Prayer of Those I Love | | |--10 Waiting for the Robert E Lee | | |--11 Dead March | | |--12 Shady Grove | | |--13 Stay Out of Town | | |--14 I've Been Here a Long Long Time | | |--15 Rolling in My Sweet Baby's Arms | | |--16 Walking in the Parlour | | |--17 Rye Whiskey | | |--18 Little Stream of Whiskey (the dying Hobo) | | |--19 Old Joe Clark | | |--20 Sourwood Mountain | | |--21 Bonnie Blue Eyes | | |--22 Bonnie Prince Charlie | | |--23 Snake Chapman's Tune | | |--24 Rock Andy | | |--25 I'll go Home to My Honey | | `--banjer days | |--Banjo Babes | | |--Banjo Babes 1 | | | |--01 Little Orchid | | | |--02 When I Go To West Virginia | | | |--03 Precious Days | | | |--04 Georgia Buck | | | |--05 Boatman | | | |--06 Rappin Shady Grove | | | |--07 See That My Grave Is Kept Clean | | | |--08 Willie Moore | | | |--09 Greasy Coat | | | |--10 I Love My Honey | | | |--11 High On A Mountain | | | |--12 Maggie May | | | `--13 Banjo Jokes Over Pickin Chicken | | |--Banjo Babes 2 | | | |--01 Hammer Down Girlfriend | | | |--02 Goin' 'Round This World | | | |--03 Down to the Door:Lost Girl | | | |--04 Time to Swim | | | |--05 Chilly Winds | | | |--06 My Drug | | | |--07 Ill Get It Myself | | | |--08 Birdie on the Wire | | | |--09 Trouble on My Mind | | | |--10 Memories of Rain | | | |--12 -

1715 Total Tracks Length: 87:21:49 Total Tracks Size: 10.8 GB

Total tracks number: 1715 Total tracks length: 87:21:49 Total tracks size: 10.8 GB # Artist Title Length 01 Adam Brand Good Friends 03:38 02 Adam Harvey God Made Beer 03:46 03 Al Dexter Guitar Polka 02:42 04 Al Dexter I'm Losing My Mind Over You 02:46 05 Al Dexter & His Troopers Pistol Packin' Mama 02:45 06 Alabama Dixie Land Delight 05:17 07 Alabama Down Home 03:23 08 Alabama Feels So Right 03:34 09 Alabama For The Record - Why Lady Why 04:06 10 Alabama Forever's As Far As I'll Go 03:29 11 Alabama Forty Hour Week 03:18 12 Alabama Happy Birthday Jesus 03:04 13 Alabama High Cotton 02:58 14 Alabama If You're Gonna Play In Texas 03:19 15 Alabama I'm In A Hurry 02:47 16 Alabama Love In the First Degree 03:13 17 Alabama Mountain Music 03:59 18 Alabama My Home's In Alabama 04:17 19 Alabama Old Flame 03:00 20 Alabama Tennessee River 02:58 21 Alabama The Closer You Get 03:30 22 Alan Jackson Between The Devil And Me 03:17 23 Alan Jackson Don't Rock The Jukebox 02:49 24 Alan Jackson Drive - 07 - Designated Drinke 03:48 25 Alan Jackson Drive 04:00 26 Alan Jackson Gone Country 04:11 27 Alan Jackson Here in the Real World 03:35 28 Alan Jackson I'd Love You All Over Again 03:08 29 Alan Jackson I'll Try 03:04 30 Alan Jackson Little Bitty 02:35 31 Alan Jackson She's Got The Rhythm (And I Go 02:22 32 Alan Jackson Tall Tall Trees 02:28 33 Alan Jackson That'd Be Alright 03:36 34 Allan Jackson Whos Cheatin Who 04:52 35 Alvie Self Rain Dance 01:51 36 Amber Lawrence Good Girls 03:17 37 Amos Morris Home 03:40 38 Anne Kirkpatrick Travellin' Still, Always Will 03:28 39 Anne Murray Could I Have This Dance 03:11 40 Anne Murray He Thinks I Still Care 02:49 41 Anne Murray There Goes My Everything 03:22 42 Asleep At The Wheel Choo Choo Ch' Boogie 02:55 43 B.J. -

Woody Guthrie's Angry Sons and Daughters

“Seeds Blowin’ Up the Highway in the South Wind”: Woody Guthrie’s Angry Sons and Daughters Roxanne Harde University of Alberta, Augustana1 Abstract Both anger and hope drive Woody Guthrie’s protest songs. Lyrics like “This Land Is Your Land” offer a hopefully angry voice that continues to be heard in the work of contemporary American singer-songwriters. This essay analyzes the ways in which Guthrie’s voice and vision continue to inform the songs of Bruce Springsteen, Steve Earle, Patty Griffin, Gillian Welch and David Rawlings, and Mary Gauthier. By bringing Guthrie’s hopeful anger that insists on justice and mercy and precludes sentimentality, hostility, and nihilism into conversation with the artists who continue his legacy of activism, this paper looks to the “Seeds” Guthrie sowed. In November 2009, at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame 25th Anniversary Concert, Bruce Springsteen opened his set with an astute and angry commentary and then introduced the perpetually enraged Tom Morello before launching into a blistering version of “The Ghost of Tom Joad,” just one of many Springsteen songs that depend upon the work of Woody Guthrie. “If you pick up the newspaper, you see millions of people out of work; you see a blood fight over decent health care for our citizens, and you see people struggling to hold on to their homes,” Springsteen said: “If Woody Guthrie were alive today, he’d have a lot to write about: high times on Wall Street and hard times on Main Street.” Relatedly, when David Rawlings performs “I Hear Them All,” with or without 1 Copyright © Roxanne Harde, 2018.