New Approaches to Old Questions in Gun Scholarship

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Neutrality Or Engagement?

LESSON 12 Neutrality or Engagement? Goals Students analyze a political cartoon and a diary entry that highlight the risks taken by civil rights workers in the 1960s. They imagine themselves in similar situations and consider conflicting motivations and responsi- bilities. Then they evaluate how much they would sacrifice for an ideal. Central Questions Many Black Mississippians—including Black ministers, teachers, and business owners—chose not to get involved in the Civil Rights Movement because of the dangers connected with participating. What do you think you would have done when Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) or Congress of Ra- cial Equality (CORE) came to your town? Was joining the movement worth the risk? Background Information Many people willingly put their lives and safety on the line to fight for civil rights. But other people chose not to get involved from fear of being punished by the police, employers, or terrorist groups. The dangers were very real: during the 1964 Freedom Summer, there were at least six murders, 29 shootings, 50 fire-bombings, more than 60 beatings, and over 400 arrests in Mississippi. Despite their fears, 80,000 residents, mostly African Americans, risked harassment and intimidation to cast ballots in the Freedom Vote of November 1963. But the next year, during 1964’s Freedom Summer, only 16,000 black Mississippians tried to register to vote in the official election that fall. “The people are scared,” James Forman of SNCC told a reporter. “They tell us, ‘All right. I’ll go down to register [to vote], but what you going to do for me when I lose my job and they beat my head?’” We hear many stories about courage and heroism, but not many about people who didn’t dare to get involved. -

MS Freedom Primer #1

FREEDOM PRIMER No. I The Convention Challenge and The Freedom Vote r, fl-if{fi---,,.-l~ff( /I ' r I FOP THE CijAL1,ENGEAT THE DEMOCRATICNATIO?!AL CX>flVENTION What Was The Democrati.c Nati.onal Convention? The Democratic National Convention was a big meeting held by the National Democratic Party at Atlantic City in August. People who represent tbe Party came to the Convention from every state in the co=try. They came to decide who would be the candidates of the Democratic Party for President and Vice-President of the tlnited St:ates in the election this year on November 3rd. They also came to decide what the Platform of the National Democratic Party would be. The Platform is a paper that says what the Party thinlcs should be done about things li.ke Housing, Education, Welfare, and Civil Rights. Why Did The Freedom Democratic Party Go To The Convention? The Freedom Democratic Party (FOP) sent a delegation of 68 people to the Convention. These people wanted to represent you at the Convention. They said that they should be seated at the Convention instead of the people sent by che 1legular Democratic Party of Mississl-ppL The 1legular Democratic Party of Mississippi only has white 1Jeople in it. But the Freedom Democratic Party is open to all people -- black and 2 white. So the delegates from the Freedom Democratic Party told the Convention it was the real 1:epresentative of all the people of Mississippi. How Was The Regular Democratic Party Delegation Chosen? The Regular Democratic Party of Mississippi also sent 68 people to t:he Convention i-n Atlantic City. -

Civil Rights and Self-Defense: the Fiction of Nonviolence, 1955-1968

CCVII. RIGHTS & SELF-DEFENSE: THE FICTION OF NONVIOLENCE, 1955-1968 by CHRISTOPHER BARRY STRAIN B.A., University of Virginia, 1993 M.A., University of Georgia, 1995 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the n:quirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the GRADUATE DMSION of the UNIVERSITY OF CAL~ORNIA, BERKELEY Committee in charge: Professor Leon F. Litwack, Chair Professor Waldo Martin Professor Ronald Takaki Spring 2000 UMI Number. 987tt823 UMI Microtorm~7t1823 Copyright 2000 by Bell 3 Howell Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edkion is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Bell 3 Howell Infomnation and Learning Company 300 NoRh Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1348 Ann Arbor, MI 48106-1348 Civil Rights and Self-Defense: The Fiction of Nonviolence, 1955-1968 m 2000 by Christopher Banry Strain H we must die-"let it not be like hops Hunted and penned in an ingloriow spot, While round u: bark IM mad and hungry dogs, Making (heir mode at our accused lot. H we must die""oh, Ist us noblydie, So that our pnedow blood may not be shed In win; then ewn the monsters we defy S~ be constrained b horar us Ihouph deed! Oh, Kinsmen! We must meet the common foe; Though far outnumbered, let us slaw us brave, Md fa Iheir Ihouand blows deal one deeth"Dbw! What though betas us Nes the open grave? Like men we'N lace the munieroue, cowardly pads, Pressed to the wall, dying, but fighting back! --"H We Must Dfe" by Claude McKay,1922 For much of its history, the southern United States was a terrible and terrifying place for black people to live. -

The Struggle for Voting Rights in Mississippi ~ the Early Years

The Struggle for Voting Rights in Mississippi ~ the Early Years Excerpted from “History & Timeline” Mississippi — the Eye of the Storm It is a trueism of the era that as you travel from the north to the south the deeper grows the racism, the worse the poverty, and the more brutal the repression. In the geography of the Freedom Movement the South is divided into mental zones according to the virulence of bigotry and oppression: the “Border States” (Delaware, Kentucky, Missouri, and the urban areas of Maryland); the “Mid South” (Virginia, the East Shore of Maryland, North Carolina, Florida, Tennessee, Arkansas, Texas); and the “Deep South” (South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Louisiana). And then there is Mississippi, in a class by itself — the absolute deepest pit of racism, violence, and poverty. During the post-Depression decades of the 1940s and 1950s, most of the South experiences enormous economic changes. “King Cotton” declines as agriculture diversifies and mechanizes. In 1920, almost a million southern Blacks work in agriculture, by 1960 that number has declined by 75% to around 250,000 — resulting in a huge migration off the land into the cities both North and South. By 1960, almost 60% of southern Blacks live in urban areas (compared to roughly 30% in 1930). But those economic changes come slowly, if at all, to Mississippi and the Black Belt areas of Alabama, Georgia, and Louisiana. In 1960, almost 70% of Mississippi Blacks still live in rural areas, and more than a third (twice the percentage in the rest of the South) work the land as sharecroppers, tenant farmers, and farm laborers. -

![Black Leadership and the Transformation of 1960S Mississippi by Sue [Lorenzi] Sojourner with Cheryl Reitan Forthcoming in Fall 2012 from University Press of Kentucky](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1780/black-leadership-and-the-transformation-of-1960s-mississippi-by-sue-lorenzi-sojourner-with-cheryl-reitan-forthcoming-in-fall-2012-from-university-press-of-kentucky-1961780.webp)

Black Leadership and the Transformation of 1960S Mississippi by Sue [Lorenzi] Sojourner with Cheryl Reitan Forthcoming in Fall 2012 from University Press of Kentucky

Learn about the Power of the Holmes County Movement THUNDER OF FREEDOM: Black Leadership and the Transformation of 1960s Mississippi by Sue [Lorenzi] Sojourner with Cheryl Reitan Forthcoming in Fall 2012 from University Press of Kentucky Excerpts from the Foreword by Historian John Dittmer, Author of LOCAL PEOPLE: The Struggle for Civil Rights in Mississippi and 1995 Winner of the Bancroft Prize in American History “Although [this coverage of Holmes Co., Mississippi. 1963-67] is one of several outstanding local community studies [. .like the ones by Crosby, Moye, and Jeffries…], THUNDER OF FREEDOM is unique in that Sojourner was a participant in the events she describes. Yet unlike other memoirs, constructed mostly from memory decades after the fact, Sojourner was compiling the primary source material for this book—documents, oral histories, photographic images—as…the events themselves were unfolding. “Insofar as I know, no civil rights memoir combines the reporting of a journalist with the experience of the organizer and the perspective of an historian. “…WE FIND UNFORGETTABLE PERSONAL PORTRAITS OF LOCAL PEOPLE LIKE ALMA MITCHELL CARNEGIE WHOSE POLITICAL INVOLVEMENT BEGAN AS A SHARECROPPER IN THE ‘20S,… BY THE ‘60S [SHE] WAS THE ‘OLDEST TO JOIN EVERY PERILOUS MOVEMENT ACTION’… “The people of Holmes County come alive in this book, the best we have on the daily lives of community organizers who joined together across lines of social class to crack open Mississippi’s ‘closed society.’ “When [Henry and Sue] Lorenzi first arrived in Holmes [in September 1964], they met Hartman Turnbow and Ralthus Hayes, leaders of a group of fourteen Holmes county blacks who defied custom and risked arrest by attempting to register to vote in the spring of 1963. -

The Movement, April 1965. Vol. 1 No. 4

THE Who Decides? Within the past four years the Negroes'( I APRIL mass protest movement in fhe South 1965 has exploded many times -- in areas all Vol. I over the black belt. The names Danville NO.4 MOVEMENT Virginia, Gadsden Alabama, S a van n a h Published by Georgia, St. Augustine Florida are known The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee of Ca lifornia at least to people who' 9re close to the movement as places where some kind of mass action has taken place. And Albany Georgia, Cambridge Maryland, Birming ham Alabama, and very lately Selma Alabama are known at least to the gen QUESTIONS RAISED BY MOSES eral public in America and in some cases (Transcript of the talk gil/ e 71 by Bob Moses at the 5th Q/111iversary of SNCC) to the entire world. In these places, thousands of people What you should suppose about SNCC got up and then murdered, that jury is participated in protests and in one year, people is that they are not fearless. like them. That's a hard thing to under 1963, 20,000 went to jail delTIonstrating. You'd have a better idea about them if stand in this country. An outgrowth of these protests has been you would suppose that they were very The only place where they can be tried an omnibus Civil Rights Act in 1964 and afraid and suppose that they were very for murder is by a jury, a local jury, a pending Voting Rights Bill. But what afraid of the people in the South that called together in Neshobe County. -

Mississippi Freedom Summer, 1964

Mississippi Freedom Summer, 1964 By Bruce Hartford Copyright © 2014. All rights reserved. For the winter soldiers of the Freedom Movement Contents Origins The Struggle for Voting Rights in McComb Mississippi Greenwood & the Mississippi Delta The Freedom Ballot of 1963 Freedom Day in Hattiesburg Mississippi Summer Project The Situation The Dilemma Pulling it Together Mississippi Girds for Armageddon Washington Does Nothing Recruitment & Training 10 Weeks That Shake Mississippi Direct Action and the Civil Rights Act Internal Tensions Lynching of Chaney, Schwerner & Goodman Freedom Schools Beginnings Freedom School Curriculum A Different Kind of School The Freedom School in McComb Impact The Medical Committee for Human Rights (MCHR) Wednesdays in Mississippi The McGhees of Greenwood McComb — Breaking the Klan Siege MFDP Challenge to the Democratic Convention The Plan Building the MFDP Showdown in Atlantic City The Significance of the MFDP Challenge The Political Fallout Some Important Points The Human Cost of Freedom Summer Freedom Summer: The Results Appendices Freedom Summer Project Map Organizational Structure of Freedom Summer Meeting the Freedom Workers The House of Liberty Freedom School Curriculum Units Platform of the Mississippi Freedom School Convention Testimony of Fannie Lou Hamer, Democratic Convention Quotation Sources [Terminology — Various authors use either "Freedom Summer" or "Summer Project" or both interchangeably. This book uses "Summer Project" to refer specifically to the project organized and led by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and the Council of Federated Organizations (COFO). We use "Freedom Summer" to refer to the totality of all Freedom Movement efforts in Mississippi over the summer of 1964, including the efforts of medical, religious, and legal organizations (see Organizational Structure of Freedom Summer for details). -

Hazel Brannon Smith: an Examination of Her Editorials on Three Pivotal Civil Rights Events

University of Mississippi eGrove Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2012 Hazel Brannon Smith: an Examination of Her Editorials on Three Pivotal Civil Rights Events Lauren Nicole Smith Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd Part of the Journalism Studies Commons Recommended Citation Smith, Lauren Nicole, "Hazel Brannon Smith: an Examination of Her Editorials on Three Pivotal Civil Rights Events" (2012). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 267. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd/267 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hazel Brannon Smith: An examination of her editorials on three pivotal civil rights events A Thesis presented in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the School of Journalism The University of Mississippi by Lauren N. Smith July 2012 Copyright Lauren N Smith 2012 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT Hazel Brannon Smith was born in Alabama but moved to Mississippi in 1936 when she acquired the Durant Times in Durant, Mississippi. Seven years later she added the Lexington Advertiser to her growing collection of newspapers and it is at the Advertiser that Smith made her greatest journalist impact. This study did a small content analysis to exam Smith’s opinion on three pivotal civil rights events: the Freedom Riders of 1961, James Meredith’s integration of the University of Mississippi in 1962, and Medgar Evers’ assassination in 1963. -

![Guide to the Moses Moon Collection, [Audiotapes]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6000/guide-to-the-moses-moon-collection-audiotapes-3916000.webp)

Guide to the Moses Moon Collection, [Audiotapes]

Guide to the Moses Moon Collection, [audiotapes] NMAH.AC.0556 Wendy Shay Partial funding for preservation and duplication of the original audio tapes provided by a National Museum of American History Collections Committee Jackson Fund Preservation Grant. Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 3 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 6 Series 1: Original Tapes.......................................................................................... 6 Series 2: Preservation Masters............................................................................. -

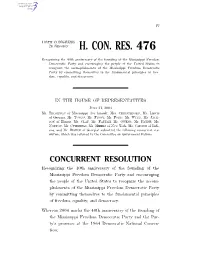

H. Con. Res. 476

IV 108TH CONGRESS 2D SESSION H. CON. RES. 476 Recognizing the 40th anniversary of the founding of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party and encouraging the people of the United States to recognize the accomplishments of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party by committing themselves to the fundamental principles of free- dom, equality, and democracy. IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES JULY 21, 2004 Mr. THOMPSON of Mississippi (for himself, Mrs. CHRISTENSEN, Mr. LEWIS of Georgia, Mr. TOWNS, Mr. FROST, Mr. FORD, Mr. WYNN, Mr. JACK- SON of Illinois, Mr. CLAY, Mr. FATTAH, Mr. OWENS, Mr. PAYNE, Ms. NORTON, Mr. CUMMINGS, Mr. MEEKS of New York, Ms. CARSON of Indi- ana, and Mr. BISHOP of Georgia) submitted the following concurrent res- olution; which was referred to the Committee on Government Reform CONCURRENT RESOLUTION Recognizing the 40th anniversary of the founding of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party and encouraging the people of the United States to recognize the accom- plishments of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party by committing themselves to the fundamental principles of freedom, equality, and democracy. Whereas 2004 marks the 40th anniversary of the founding of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party and the Par- ty’s presence at the 1964 Democratic National Conven- tion; 2 Whereas the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party was es- tablished in order to break the reign of white supremacy in Mississippi; Whereas the original members of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party delegation in 1964 were Lawrence Guyot, Peggy J. Conner, Victoria Gray, Edwin King, Aaron Henry, Fannie Lou Hamer, Annie Devine, Helen Anderson, A.D. Beittel, Elizabeth Blackwell, Marie Blalock, Sylvester Bowens, J.W. -

Holmes Co. Mississippi

Praxis International "Integrating Theory and Practice " II "GOT TO WORDS, IMAGES, AND INTERVIEWS by Sue [Lorenzi] Sojourner a Northern white civil rights organizer who lived and worked with the Holmes County Movement people for five years in the 19605 On permanent display at the Domestic Abuse Intervention Center 202 East Superior Street \ Duluth, Minnesota '~r Rural Technical Assistance on ~ ~ Violence Against Women Exhibition and brochure produced by Praxis International, Inc.; document production support provided by the Puffin Foundation Ltd., Teaneck, N.J. This project was supported by Grant No. 98-WR-VX-KOOl awarded by the Violence Against Women Office, Office of Justice Programs, u.s. Department of Justice. Points of view in this document are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the official position of the u.s. Department of Justice "Fear of freedom. It is fear of or lack of faith in the people. But if the people cannot be trusted, there is no reason for liberation. ..the revolution is not even carried out for the people, but "by" the people for the leaders - a complete self-negation. " Paulo Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed This exhibit is a part of the Community Organizing Teaching Center created by Praxis, International*. The goal of the center is to document projects nationally and internationally that have met the challenges of violence, poverty and other forms of oppression through community organizing efforts. The documented projects have developed a local response to a local problem, by involving community members affected by the problem, and by creating environments in which self- determination and decision-making power remain with the people as they work to improve their own lives. -

Firearms Policy and the Black Community: an Assessment of the Modern Orthodoxy Nicholas J

Fordham Law School FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History Faculty Scholarship 2013 Firearms Policy and the Black Community: An Assessment of the Modern Orthodoxy Nicholas J. Johnson Fordham University School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Constitutional Law Commons, Human Rights Law Commons, and the Second Amendment Commons Recommended Citation Nicholas J. Johnson, Firearms Policy and the Black Community: An Assessment of the Modern Orthodoxy, 45 Conn. L. Rev. 1491 (2013) Available at: http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/faculty_scholarship/535 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONNECTICUT LAW REVIEW VOLUME 45 JULY 2013 NUMBER 5 Article Firearms Policy and the Black Community: An Assessment of the Modern Orthodoxy NICHOLAS J. JOHNSON The heroes of the modern civil rights movement were more than just stoic victims of racist violence. Their history was one of defiance and fighting long before news cameras showed them attacked by dogs and fire hoses. When Fannie Lou Hamer revealed she kept a shotgun in every corner of her bedroom, she was channeling a century old practice. And when delta share cropper Hartman Turnbow, after a shootout with the Klan, said “I don’t figure I was being non-nonviolent, (yes non-nonviolent) I was just protecting my family”, he was invoking an evolved tradition that embraced self-defense and disdained political violence.