Italy in the Thirteenth Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tables of Contemporary Chronology, from the Creation to A. D. 1825

: TABLES OP CONTEMPORARY CHUONOLOGY. FROM THE CREATION, TO A. D. 1825. \> IN SEVEN PARTS. "Remember the days of old—consider the years of many generations." 3lorttatttt PUBLISHED BY SHIRLEY & HYDE. 1629. : : DISTRICT OF MAItfE, TO WIT DISTRICT CLERKS OFFICE. BE IT REMEMBERED, That on the first day of June, A. D. 1829, and in the fifty-third year of the Independence of the United States of America, Messrs. Shiraey tt Hyde, of said District, have deposited in this office, the title of a book, the right whereof they claim as proprietors, in the words following, to wit Tables of Contemporary Chronology, from the Creation, to A.D. 1825. In seven parts. "Remember the days of old—consider the years of many generations." In conformity to the act of the Congress of the United States, entitled " An Act for the encouragement of learning, by securing the copies of maps, charts, and books, to the authors and proprietors of such copies, during the times therein mentioned ;" and also to an act, entitled "An Act supplementary to an act, entitled An Act for the encouragement of learning, by securing the copies of maps, charts and books, to the authors and proprietors of such copies, during the times therein mentioned ; and for extending the benefits thereof to the arts of designing, engraving, and etching historical and other prints." J. MUSSEV, Clerk of the District of Maine. A true copy as of record, Attest. J MUSSEY. Clerk D. C. of Maine — TO THE PUBLIC. The compiler of these Tables has long considered a work of this sort a desideratum. -

The Thirteenth Century

1 SHORT HISTORY OF THE ORDER OF THE SERVANTS OF MARY V. Benassi - O. J. Diaz - F. M. Faustini Chapter I THE THIRTEENTH CENTURY From the origins of the Order (ca. 1233) to its approval (1304) The approval of the Order. In the year 1233... Florence in the first half of the thirteenth century. The beginnings at Cafaggio and the retreat to Monte Senario. From Monte Senario into the world. The generalate of St. Philip Benizi. Servite life in the Florentine priory of St. Mary of Cafaggio in the years 1286 to 1289. The approval of the Order On 11 February 1304, the Dominican Pope Benedict XI, then in the first year of his pontificate, sent a bull, beginning with the words Dum levamus, from his palace of the Lateran in Rome to the prior general and all priors and friars of the Order of the Servants of Saint Mary. With this, he gave approval to the Rule and Constitutions they professed, and thus to the Order of the Servants of Saint Mary which had originated in Florence some seventy years previously. For the Servants of Saint Mary a long period of waiting had come to an end, and a new era of development began for the young religious institute which had come to take its place among the existing religious orders. The bull, or pontifical letter, of Pope Benedict XI does not say anything about the origins of the Order; it merely recognizes that Servites follow the Rule of St. Augustine and legislation common to other orders embracing the same Rule. -

Elizabeth Thomas Phd Thesis

'WE HAVE NOTHING MORE VALUABLE IN OUR TREASURY': ROYAL MARRIAGE IN ENGLAND, 1154-1272 Elizabeth Thomas A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2010 Full metadata for this item is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/2001 This item is protected by original copyright Declarations (i) I, Elizabeth Thomas, hereby certify that this thesis, which is approximately 80,000 words in length, has been written by me, that it is the record of work carried out by me and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. I was admitted as a research student in September, 2005 and as a candidate for the degree of Ph.D. in September, 2005, the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St Andrews between 2005 and 2009. Date: Signature of candidate: (ii) I hereby certify that the candidate has fulfilled the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations appropriate for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of St Andrews and that the candidate is qualified to submit this thesis in application for that degree. Date: Signature of supervisor: (iii) In submitting this thesis to the University of St Andrews we understand that we are giving permission for it to be made available for use in accordance with the regulations of the University Library for the time being in force, subject to any copyright vested in the work not being affected thereby. -

Saint John Henry Newman

SAINT JOHN HENRY NEWMAN Chronology 1801 Born in London Feb 21 1808 To Ealing School 1816 First conversion 1817 To Trinity College, Oxford 1822 Fellow, Oriel College 1825 Ordained Anglican priest 1828-43 Vicar, St. Mary the Virgin 1832-33 Travelled to Rome and Mediterranean 1833-45 Leader of Oxford Movement (Tractarians) 1843-46 Lived at Littlemore 1845 Received into Catholic Church 1847 Ordained Catholic priest in Rome 1848 Founded English Oratory 1852 The Achilli Trial 1854-58 Rector, Catholic University of Ireland 1859 Opened Oratory school 1864 Published Apologia pro vita sua 1877 Elected first honorary fellow, Trinity College 1879 Created cardinal by Pope Leo XIII 1885 Published last article 1888 Preached last sermon Jan 1 1889 Said last Mass on Christmas Day 1890 Died in Birmingham Aug 11 Other Personal Facts Baptized 9 Apr 1801 Father John Newman Mother Jemima Fourdrinier Siblings Charles, Francis, Harriett, Jemima, Mary Ordination (Anglican): 29 May 1825, Oxford Received into full communion with Catholic Church: 9 October 1845 Catholic Confirmation (Name: Mary): date 1 Nov 1845 Ordination (Catholic): 1 June 1847 in Rome First Mass 5 June 1847 Last Mass 25 Dec 1889 Founder Oratory of St. Philip Neri in England Created Cardinal-Deacon of San Giorgio in Velabro: 12 May 1879, in Rome, by Pope Leo XIII Motto Cor ad cor loquitur—Heart speaks to heart Epitaph Ex umbris et imaginibus in veritatem—Out of shadows and images into the truth Declared Venerable: 22 January 1991 by Pope St John Paul II Beatified 19 September 2010 by Pope Benedict XVI Canonized 13 October 2019 by Pope Francis Feast Day 9 October First Approved Miracle: 2001 – healing of Deacon Jack Sullivan (spinal condition) in Boston, MA Second Approved Miracle: 2013 – healing of Melissa Villalobos (pregancy complications) in Chicago, IL Newman College at Littlemore Bronze sculpture of Newman kneeling before Fr Dominic Barberi Newman’s Library at the Birmingham Oratory . -

The Physician Who Became Pope

The Linacre Quarterly Volume 28 | Number 1 Article 4 February 1961 The hP ysician Who Became Pope William M. Crawford Follow this and additional works at: http://epublications.marquette.edu/lnq Recommended Citation Crawford, William M. (1961) "The hP ysician Who Became Pope," The Linacre Quarterly: Vol. 28 : No. 1 , Article 4. Available at: http://epublications.marquette.edu/lnq/vol28/iss1/4 :iUMMARY proper understanding and preci The foregoing comments repre ation of those fundament norms sent nothing more than a standard will make it possible to erceive synopsis of current theological the total significance of ti practi teaching on the question of ectopic cal conclusion expressed Direc- The Physician pregnancy. Emphasis has been tive 20: placed on the basic moral prin In extrauterine pregnancy tl affected part of the mother (e.g., ar. vary or ciples on which that teaching de fallopian tube) may be rem. ed, even Who Became Pope pends, in the hope that certain though the life of the fetus thus in misconceptions of our position may directly terminated, provided e opera· tion cannot be postponed with . notably thereby be corrected. Only a increasing the danger to the , ther. WILLIAM M. CRAWFORD, M.D. Fort Worth, Texas branches of philosophical learning, By MODERN standards, the transformation of a successful it was not abnormal for Petrus to practicing physician into a pope is pass from the logic of Aristotle almost unthinkable. Yet this is pre and the Arabian philosophers to cisely what happened in the thir medicine. teenth century when the renowned During the middle of the thir Petrus Hispanus exchanged his teenth century Petrus was a teach scalpel for the papal ring and keys er of medicine at Siena when the to become Pope John XXI. -

The Manuscript Vat. Lat. 2463: Some Considerations About a Medieval Medical Volume of Galvanus De Levanto

The manuscript Vat. lat. 2463: some considerations about a medieval medical volume of Galvanus de Levanto by Luca Salvatelli In nomine Domini Nostri Ihesu Christi Amen. Thesaurus corporalis prelatorum Ecclesiae dei et magnatum fidelium Galvani Ianuansis de Levanto umbrae medici1 contra nocumento digestionis stomaci […]. Written in red ink, these are the first words of the medical codex MS Vat. lat. 2463 #reser$ed in the Vatical %ibrary. Meas&rin' 265 x 165 mm, it is a refined small man&script of 116 $ell&m lea$es (ff. *V [I+** #aper, ***+*V membr.2], 116, *- [pa#er])", that dates to the first half of the 14th century (1340-1343). *t has a do&ble col&mn of writin' (171x130mm, interspace 15mm), penned by an *talian littera textualis, in what is #robably 1olognese handwriting. 2he $ol&me is com#rised of fo&r medical works of 3al$an&s *an&ansis de %e$anto, listed accordin' to the index on f. *r index at f. **r, which was written in a ele'ant formal writin' at the end of 16th century 4 a) Thesaurus corporalis praelatorum ecclesiae dei et magnatum fidelium (ff. 1r+!5$., b) Remedium solutivum contra catarrum ad eosdem praelatos et principes (ff. 69r+05$., c) Paleofilon curativus languoris articolorum ad Ven(erabilem) Archiep(iscopum)Ramen (ff. 79r-110r., d) Salutare carisma ex Sacra Scriptura (ff. 110r-114r). 2he frontes#ice on f. 1r contains an ill&minated panel (71x121mm), with a dedicatory scene on a 'old back'ro&nd. *t shows a tons&red doctor, who offers an o#en $ol&me to the pope on his throne. -

The Christian Ethics of Dante's Purgatory

MEDIUM ÆVUM, VOL. LXXXIII, No. 2, pp. 266–287 © SSMLL, 2014 THE CHRISTIAN ETHICS OF DANTE’S PURGATORY It might appear straightforward, on a first reading, that Dante’s Purgatory represents a penitential journey guided by Christian ethics to God. For most of the poem’s history, indeed, Purgatory has been read broadly in this way. In the second half of the twentieth century, however, a parallel interpretation emerged. Influenced by Dante’s dualistic theory of man’s two ethical goals (one temporal and one eternal), many scholars have argued that Purgatory represents a secular journey guided by philosophical principles to a temporal happiness. This article presents three major counter-arguments to the secular reading of Purgatory, a reading proposed most powerfully in recent scholarship by John A. Scott’s monograph Dante’s Political Purgatory.1 First, it proposes a new way to read the poem as informed by Dante’s dualistic theory which does not entail a forced reading of Purgatory in overly political terms. Secondly, it demonstrates how Dante forged his vision of Purgatory through two areas of distinctively Christian theory and practice which had risen to particular prominence in the thirteenth century: the newly crystallized doctrine of Purgatory and the tradition of the seven capital vices (or deadly sins) in penitential ethics.2 Thirdly, it argues that the region embodies an explicit reorientation from natural to supernatural ethics, from pagan to Christian exempla, and from this world to the heavenly city. Where Scott has argued for a ‘political -

Pedigree of the Wilson Family N O P

Pedigree of the Wilson Family N O P Namur** . NOP-1 Pegonitissa . NOP-203 Namur** . NOP-6 Pelaez** . NOP-205 Nantes** . NOP-10 Pembridge . NOP-208 Naples** . NOP-13 Peninton . NOP-210 Naples*** . NOP-16 Penthievre**. NOP-212 Narbonne** . NOP-27 Peplesham . NOP-217 Navarre*** . NOP-30 Perche** . NOP-220 Navarre*** . NOP-40 Percy** . NOP-224 Neuchatel** . NOP-51 Percy** . NOP-236 Neufmarche** . NOP-55 Periton . NOP-244 Nevers**. NOP-66 Pershale . NOP-246 Nevil . NOP-68 Pettendorf* . NOP-248 Neville** . NOP-70 Peverel . NOP-251 Neville** . NOP-78 Peverel . NOP-253 Noel* . NOP-84 Peverel . NOP-255 Nordmark . NOP-89 Pichard . NOP-257 Normandy** . NOP-92 Picot . NOP-259 Northeim**. NOP-96 Picquigny . NOP-261 Northumberland/Northumbria** . NOP-100 Pierrepont . NOP-263 Norton . NOP-103 Pigot . NOP-266 Norwood** . NOP-105 Plaiz . NOP-268 Nottingham . NOP-112 Plantagenet*** . NOP-270 Noyers** . NOP-114 Plantagenet** . NOP-288 Nullenburg . NOP-117 Plessis . NOP-295 Nunwicke . NOP-119 Poland*** . NOP-297 Olafsdotter*** . NOP-121 Pole*** . NOP-356 Olofsdottir*** . NOP-142 Pollington . NOP-360 O’Neill*** . NOP-148 Polotsk** . NOP-363 Orleans*** . NOP-153 Ponthieu . NOP-366 Orreby . NOP-157 Porhoet** . NOP-368 Osborn . NOP-160 Port . NOP-372 Ostmark** . NOP-163 Port* . NOP-374 O’Toole*** . NOP-166 Portugal*** . NOP-376 Ovequiz . NOP-173 Poynings . NOP-387 Oviedo* . NOP-175 Prendergast** . NOP-390 Oxton . NOP-178 Prescott . NOP-394 Pamplona . NOP-180 Preuilly . NOP-396 Pantolph . NOP-183 Provence*** . NOP-398 Paris*** . NOP-185 Provence** . NOP-400 Paris** . NOP-187 Provence** . NOP-406 Pateshull . NOP-189 Purefoy/Purifoy . NOP-410 Paunton . NOP-191 Pusterthal . -

Family Tree Maker

Ancestors of Ulysses Simpson Grant Generation No. 1 1. President Ulysses Simpson Grant, born 27 Apr 1822 in Point Pleasant, Clermont Co., OH; died 23 Jul 1885 in Mount McGregor, Saratoga Co., NY. He was the son of 2. Jesse Root Grant and 3. Hannah Simpson. He married (1) Julia Boggs Dent 22 Aug 1848. She was born 26 Jan 1826 in White Haven Plantation, St. Louis Co. MO, and died 14 Dec 1902 in Washington, D. C.. She was the daughter of "Colonel" Frederick Fayette Dent and Ellen Bray Wrenshall. Generation No. 2 2. Jesse Root Grant, born 23 Jan 1794 in Greensburg, Westmoreland Co., PA; died 29 Jan 1873 in Covington, Campbell Co., KY. He was the son of 4. Noah Grant III and 5. Rachel Kelley. He married 3. Hannah Simpson 24 Jun 1821 in The Simpson family home. 3. Hannah Simpson, born 23 Nov 1798 in Horsham, Philadelphia Co., PA; died 11 May 1883 in Jersey City, Coventry Co., NJ. She was the daughter of 6. John Simpson, Jr. and 7. Rebecca Weir. Children of Jesse Grant and Hannah Simpson are: 1 i. President Ulysses Simpson Grant, born 27 Apr 1822 in Point Pleasant, Clermont Co., OH; died 23 Jul 1885 in Mount McGregor, Saratoga Co., NY; married Julia Boggs Dent 22 Aug 1848. ii. Samuel Simpson Grant iii. Orville Grant iv. Clara Grant v. Virginia "Nellie" Grant vi. Mary Frances Grant Generation No. 3 4. Noah Grant III, born 20 Jun 1748; died 14 Feb 1819 in Maysville, Mason Co., KY. He was the son of 8. -

Church of Saint Michael

WLOPEFM QFJBPJBP Church of Saint Michael Saturday: 4:30PM God's sons and daughters in Sunday: 8:00AM, 10:30AM Tuesday: 6:30PM Chapel Farmington, Minnesota Wednesday: 8:30AM Chapel Thursday: 8:30AM Chapel Our Mission Friday: 8:30AM Chapel To be a welcoming Catholic community CLKCBPPFLKLK centered in the Eucharist, inving all to live the Saturday: 3:15-4:15PM Gospel and grow in faith. AKLFKQFKD LC QEB SF@HF@H If you or a family member needs to October 20, 2019—World Mission Sunday receive the Sacrament of Anoinng please call the parish office, 651-463-3360. B>MQFPJJ Bapsm class aendance is required. Bapsm I is offered the 3rd Thursday of the month at 7pm. Bapsm II is offered the 2nd Thursday of the month at 6:30pm. Group Bapsm is held the 2nd Sunday of the month at 12:00noon. (Schedule can vary) Email [email protected] or call 651-463-5257. M>QOFJLKVLKV Please contact the Parish Office. Allow at least 9 months to prepare for the Sacrament of Marriage. HLJB?LRKA ER@E>OFPQFPQ If you or someone you know is homebound and would like to receive Holy Communion, please contact Jennifer Schneider 651-463-5224. PO>VBO LFKBFKB Email your prayer requests to: [email protected] or call 651-463-5224 P>OFPE OCCF@B HLROPROP Monday through Friday 8:00am-4:00pm Phone—651-463-3360 [email protected] BRIIBQFK DB>AIFKBFKB Monday noon for the following Sunday bullen, submit to: info@stmichael- farmington.org 22120 Denmark Avenue—Farmington MN 55024—www.stmichael-farmington.org ▪ October 20, 2019 2 From the Pastor THAT CHRIST MAY DWELL IN YOUR 4:30 PM Mass and to bless our sanctuary crucifix. -

The Augustinian Vol VII

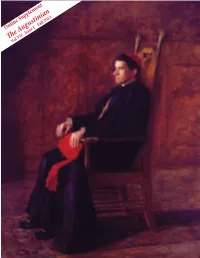

Online Supplement The Augustinian Vol VII . Issue I Fall 2012 Volume VII . Issue I The Augustinian Fall 2012 - Online Supplement Augustinian Cardinals Fr. Prospero Grech, O.S.A., was named by Pope Benedict XVI to the College of Cardinals on the Feast of the Epiphany, January 6, 2012. On February 18, 2012, when he received the red biretta, he joined the ranks of twelve other Augustinian Friars who have served as Cardinals. This line stretches back to 1378, when Bonaventura Badoardo da Padova, O.S.A., was named Cardinal, the first Augustinian Friar so honored. Starting with the current Cardinal, Prospero Grech, read a biographical sketch for each of the thirteen Augustinian Cardinals. Friars of the Province of Saint Thomas of Villanova Sebastiano Martinelli, O.S.A., the most recent Augustinian Cardinal prior to Cardinal Prospero Grech, O.S.A., served as Apostolic Delegate to the United States (1896 - 1902). While serving in this position, he made several trips to visit Augustinian sites. In 1897, while visiting Villanova, he was pho- tographed with the professed friars of the Province. Among these men were friars who served in leader- ship roles for the Province, at Villanova College, and in parishes and schools run by the Augustinians. Who were these friars and where did they serve? Read a sketch, taken from our online necrology, Historical information for Augustinian Cardinals for each of the 17 friars pictured with Archbishop supplied courtesy of Fr. Michael DiGregorio, O.S.A., Sebastiano Martinelli. Vicar General of the Order of St. Augustine. On the Cover: Thomas Eakins To read more about Archbishop Martinelli and Portrait of Sebastiano Cardinal Martinelli, 1902 Cardinal Grech, see the Fall 2012 issue of The Oil on panel Augustinian magazine, by visiting: The Armand Hammer Collection http://www.augustinian.org/what-we-do/media- Gift of the Armand Hammer Foundation room/publications/publications Hammer Museum, Los Angeles Photo by Robert Wedemeyer Copyright © 2012, Province of St. -

PDF) 978-3-11-066078-4 E-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-065796-8

The Crisis of the 14th Century Das Mittelalter Perspektiven mediävistischer Forschung Beihefte Herausgegeben von Ingrid Baumgärtner, Stephan Conermann und Thomas Honegger Band 13 The Crisis of the 14th Century Teleconnections between Environmental and Societal Change? Edited by Martin Bauch and Gerrit Jasper Schenk Gefördert von der VolkswagenStiftung aus den Mitteln der Freigeist Fellowship „The Dantean Anomaly (1309–1321)“ / Printing costs of this volume were covered from the Freigeist Fellowship „The Dantean Anomaly 1309-1321“, funded by the Volkswagen Foundation. Die frei zugängliche digitale Publikation wurde vom Open-Access-Publikationsfonds für Monografien der Leibniz-Gemeinschaft gefördert. / Free access to the digital publication of this volume was made possible by the Open Access Publishing Fund for monographs of the Leibniz Association. Der Peer Review wird in Zusammenarbeit mit themenspezifisch ausgewählten externen Gutachterin- nen und Gutachtern sowie den Beiratsmitgliedern des Mediävistenverbands e. V. im Double-Blind-Ver- fahren durchgeführt. / The peer review is carried out in collaboration with external reviewers who have been chosen on the basis of their specialization as well as members of the advisory board of the Mediävistenverband e.V. in a double-blind review process. ISBN 978-3-11-065763-0 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-066078-4 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-065796-8 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Control Number: 2019947596 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de.