From Devaki to Yashoda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

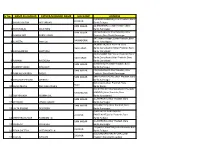

Signatory ID Name CIN Company Name 02700003 RAM TIKA

Signatory ID Name CIN Company Name 02700003 RAM TIKA U55101DL1998PTC094457 RVS HOTELS AND RESORTS 02700032 BANSAL SHYAM SUNDER U70102AP2005PTC047718 SHREEMUKH PROPERTIES PRIVATE 02700065 CHHIBA SAVITA U01100MH2004PTC150274 DEJA VU FARMS PRIVATE LIMITED 02700070 PARATE VIJAYKUMAR U45200MH1993PTC072352 PARATE DEVELOPERS P LTD 02700076 BHARATI GHOSH U85110WB2007PTC118976 ACCURATE MEDICARE & 02700087 JAIN MANISH RAJMAL U45202MH1950PTC008342 LEO ESTATES PRIVATE LIMITED 02700109 NATESAN RAMACHANDRAN U51505TN2002PTC049271 RESHMA ELECTRIC PRIVATE 02700110 JEGADEESAN MAHENDRAN U51505TN2002PTC049271 RESHMA ELECTRIC PRIVATE 02700126 GUPTA JAGDISH PRASAD U74210MP2003PTC015880 GOPAL SEVA PRIVATE LIMITED 02700155 KRISHNAKUMARAN NAIR U45201GJ1994PTC021976 SHARVIL HOUSING PVT LTD 02700157 DHIREN OZA VASANTLAL U45201GJ1994PTC021976 SHARVIL HOUSING PVT LTD 02700183 GUPTA KEDAR NATH U72200AP2004PTC044434 TRAVASH SOFTWARE SOLUTIONS 02700187 KUMARASWAMY KUNIGAL U93090KA2006PLC039899 EMERALD AIRLINES LIMITED 02700216 JAIN MANOJ U15400MP2007PTC020151 CHAMBAL VALLEY AGRO 02700222 BHAIYA SHARAD U45402TN1996PTC036292 NORTHERN TANCHEM PRIVATE 02700226 HENDIN URI ZIPORI U55101HP2008PTC030910 INNER WELLSPRING HOSPITALITY 02700266 KUMARI POLURU VIJAYA U60221PY2001PLC001594 REGENCY TRANSPORT CARRIERS 02700285 DEVADASON NALLATHAMPI U72200TN2006PTC059044 ZENTERE SOLUTIONS PRIVATE 02700322 GOPAL KAKA RAM U01400UP2007PTC033194 KESHRI AGRI GENETICS PRIVATE 02700342 ASHISH OBERAI U74120DL2008PTC184837 ASTHA LAND SCAPE PRIVATE 02700354 MADHUSUDHANA REDDY U70200KA2005PTC036400 -

Namdev Life and Philosophy Namdev Life and Philosophy

NAMDEV LIFE AND PHILOSOPHY NAMDEV LIFE AND PHILOSOPHY PRABHAKAR MACHWE PUBLICATION BUREAU PUNJABI UNIVERSITY, PATIALA © Punjabi University, Patiala 1990 Second Edition : 1100 Price : 45/- Published by sardar Tirath Singh, LL.M., Registrar Punjabi University, Patiala and printed at the Secular Printers, Namdar Khan Road, Patiala ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am grateful to the Punjabi University, Patiala which prompted me to summarize in tbis monograpb my readings of Namdev'\i works in original Marathi and books about him in Marathi. Hindi, Panjabi, Gujarati and English. I am also grateful to Sri Y. M. Muley, Director of the National Library, Calcutta who permitted me to use many rare books and editions of Namdev's works. I bave also used the unpubIi~bed thesis in Marathi on Namdev by Dr B. M. Mundi. I bave relied for my 0pIDlOns on the writings of great thinkers and historians of literature like tbe late Dr R. D. Ranade, Bhave, Ajgaonkar and the first biographer of Namdev, Muley. Books in Hindi by Rabul Sankritya)'an, Dr Barathwal, Dr Hazariprasad Dwivedi, Dr Rangeya Ragbav and Dr Rajnarain Maurya have been my guides in matters of Nath Panth and the language of the poets of this age. I have attempted literal translations of more than seventy padas of Namdev. A detailed bibliography is also given at the end. I am very much ol::lig(d to Sri l'and Kumar Shukla wbo typed tbe manuscript. Let me add at the end tbat my family-god is Vitthal of Pandbarpur, and wbat I learnt most about His worship was from my mother, who left me fifteen years ago. -

Sri Rukmini Kalyanam Saturday, September 26Th 2015 1:30 PM – 6:00 PM

Hindu Community and Cultural Center 1232 Arrowhead Ave, Livermore, CA 94551 A Non-Profit Organization since 1977 Tax ID# 94-2427126; Inc# D0821589 Shiva-Vishnu Temple Tel: 925-449-6255; Fax: 925-455-0404 Om Namah Shivaya Om Namo Narayanaya Web: http://www.livermoretemple.org Sri Rukmini Kalyanam Saturday, September 26th 2015 1:30 PM – 6:00 PM Vasudeva Sutham Devam Kamsa Chaanoora Mardhanam Devaki Paramaanandham Krishnam Vande' Jagathgurum Sri Rukmini Kalyanam is a very auspicious and sacred event planned for the first time on Saturday, September 26th 2015 at Shiva Vishnu Temple. Rukmini is the incarnation Goddess Lakshmi for pairing with Lord Krishna who is incarnation of Lord Vishnu. Rukmi, the brother of Rukmini, tries to get her married to Sisupala. Rukmini writes to Lord Krishna and sends the letter through a brahmin priest. Lord Krishna rushes to fetch Rukmini and takes her to Dwaraka by defeating all the kings. It is a practice in hindu families to make unmarried girls/boys recite, listen, perform or witness Rukmini kalyanam so that marriage gets settled soon. Also they believe that power of recital can make them get suitable spouses. Please plan on participating in this auspicious event and receive divine blessings Event Schedule 1:30 PM Rukmini Kalyana Ghattam - Parayanam 3:00 PM Edurukolu Utsavam 3:30 PM Unjal Seva 4:00 PM Kalyanotsavam 6:00 PM Theertha Prasadam and Kalyana Bhojanam for all devotees Instagram.com/livermoretemple facebook.com/livermoretemple twitter.com/livermoretemple Hindu Community and Cultural Center 1232 Arrowhead Ave, Livermore, CA 94551 A Non-Profit Organization since 1977 Tax ID# 94-2427126; Inc# D0821589 Shiva-Vishnu Temple Tel: 925-449-6255; Fax: 925-455-0404 Om Namah Shivaya Om Namo Narayanaya Web: http://www.livermoretemple.org Sri Rukmini Kalyanam - Significance Sri Rukmini Kalyanam has great religious significance. -

KRISHNA Pastimes of Krishna in Vrindavana

Vrajanandana KRISHNA Pastimes of Krishna in Vrindavana Based on KRISHNA - The Supreme Personality of Godhead by His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada Founder-Acharya of ISKCON Adapted for children by Yaduraja Dasa Sankirtana Seva Trust Hare Krishna Hill, Chord Road, Bangalore-10 A book in English Vrajananda Krishna - Pastimes of Krishna in Vrindavana Based on: KRISHNA - The Supreme Personality of Godhead by His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada Founder-Acharya of ISKCON Adapted for children by Sri Yaduraja Dasa Published by Sankirtana Seva Trust, Hare Krishna Hill, Chord Road, Bangalore-10 Printed at Brilliant Printers Pvt. Ltd. Lottegollahalli, Bangalore [Total no. of Pages : 144, Size : 1/8 Crown] © 2014, Sankirtan Seva Trust All Rights Reserved ISBN : 81-8239-020-6 First Printing 2007 : 5000 Copies Second Printing 2010 (Revised) : 5000 Copies Third Printing 2011 (Revised) : 5000 Copies Fourth Printing 2014 : 1000 Copies Fifth Printing 2015 : 1000 Copies Readers interested in the subject matter of this book are invited by the International Society for Krishna Consciousness to correspond with its Secretary at the following address: International Society for Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON) Hare Krishna Hill, Chord Road, Rajajinagar, Bangalore - 560 010. Tel: 080-23471956 Mobile: 9341211119 Email: [email protected] Website: www.iskconbangalore.org Contents Introduction ......................................................................... 5 Prologue: The Tears of Mother Earth ................................ 6 1. The Curse .................................................................... 7 2. A Visit from Narada Muni .......................................... 11 3. The Divine Plan Unfolds ........................................... 13 4. The Birth of Lord Krishna ......................................... 16 5. Goddess Durga .......................................................... 20 6. Kamsa’s Change of Heart......................................... 24 7. The Meeting of Nanda Maharaja and Vasudeva ... -

42. Consummation in Nanda-Nandana

Chapter 42. Consummation in Nanda-Nandana “Meanwhile, the seventh pregnancy came! And surprisingly, it was aborted in the seventh month! Should they inform Kamsa? If yes, how? They couldn’t find the answer. When Kamsa learned about this, he suspected that the sister was capable of some stratagem to deceive him, so he put her and her husband in a closely guarded prison.” The sage Suka started telling about the most glorious event, which revealed the reality of Krishna incarna- tion. Krishna is born to Devaki in prison “Devaki and Vasudeva, who spent their days in prison, were indistinguishable from mad people. They sat with unkempt hair, lean and lanky through want of appetite and the wherewithal to feed their bodies. They had no mind to eat or sleep. They were slowly consumed by grief over the children they had lost. When their prison life entered its second year, Devaki conceived for the eighth time! It was wondrous! What a transformation it brought about! The faces of Devaki and Vasudeva, which had drooped and dried up, suddenly blossomed like lotuses in full bloom. They shone with a strange splendour. “Their bodies, which were reduced to mere skin and bone, as if they had been dehydrated, took on flesh, be- came round and smooth, and shone with a charming golden hue. Devaki’s cell was fragrant with pleasing aromas. It cast a wondrous light and was filled with inexplicable music and the jingle of dancing feet. Amazing sights and sounds indeed! Devaki and Vasudeva became aware of these happenings but were afraid to inform Kamsa, lest he hack the womb into pieces in his vindictive frenzy. -

Lord Krishna-The Jagat Guru

[Draw your reader in with an engaging abstract. It is typically a short summary of the document. When you’re ready to add your content, just click here and start typing.] Lord Krishna- the Jagat Guru K Sriram Sri Ramana Bhaktha Samajam Chennai Lord Krishna– The Jagat Guru [Loka Maha Guru] Devaki Paramanandam Vasudeva sudam Devam Kamsa Chanoora MardanamI Devaki Paramanandam Sri krishnam vande Jagat GurumII The One who was born to Vasudeva, the One who annihilated Kamsa & Chanoora, the One whose very name plunges his mother Devaki into ecstacy, To Him, the Loka Maha Guru, Lord Krishna, I pay my humble obeisance. Page 1 of 9 Introduction It is surprising to note that Lord Krishna’s life represents the average person of today. Brought up in a lower middle class family, the small boy spends his entire time in his studies under very trying circumstances. Higher studies take him to the cities and even overseas. His circumstances change totally when he converts his Knowledge into Experience. Experience takes him to corridors of Power which, again, lands him in a completely different atmosphere. His later days don’t even remotely resemble his childhood days. He could hardly return to his native village which was his dwelling place as a child. Finally, he leaves the world as a loner in yet another totally different atmosphere. Lord Krishna’s life exactly corresponds to such a life of an average person today in spite of the fact that 5000 years have elapsed since his appearance on this planet. He was brought up in a cowherd’s family as a child. -

Sr No. NAME AS AADHAR FATHER/HUSBAND NAME ULB

Sr No. NAME AS AADHAR FATHER/HUSBAND NAME ULB NAME ADDRESS 0;AHIRAN ZAIDPUR;;Uttar Pradesh ;Bara ZAIDPUR 1 VAIMUN NISHA MO SARVAR Banki;Zaidpur RAM NAGAR 20;KADIRABAD;;Uttar Pradesh ;Bara 2 KANDHAILAL SALIK RAM Banki;Ramnagar RAM NAGAR 157;BARABANKI RAM NAGAR;;Uttar 3 RAMSAHARE PARSHU RAM Pradesh ;Bara Banki;Ramnagar 347;Gandhi Nagar;;Uttar Pradesh ;Bara NAWABGANJ 4 SUNEETA Prem Lal Banki;Nawabganj 14;MULIHA;Uttar Pradesh ;Bara DARIYABAD Banki;Dariyabad;0;;Uttar Pradesh ;Bara 5 SHIVSHANKAR SANTRAM Banki;Dariyabad 36;36;BANNE TALE;Uttar Pradesh ;Bara DARIYABAD Banki;Dariyabad;;Uttar Pradesh ;Bara 6 RAJRANI RAJENDRA Banki;Dariyabad RAM NAGAR 3;RAMNAGAR;;Uttar Pradesh ;Bara 7 RAMESH YADAV BHAGAUTI Banki;Ramnagar RAM NAGAR 209;BARABANKI RAM NAGAR;;Uttar 8 RAM JAS MAURYA BADLU Pradesh ;Bara Banki;Ramnagar RAM NAGAR 344/A;RAM NAGAR;;Uttar Pradesh ;Bara 9 BHAGAUTI PRASAD GHIRRAU Banki;Ramnagar 0;Nai basti;;Uttar Pradesh ;Bara Banki 10 Ganga Mishra Ram Lalan Mishra Banki;Banki 0;BHEETRI PEERBATAWAN CHOTA JAIN NAWABGANJ MANDIR;;Uttar Pradesh ;Bara 11 OM PRAKASH MUNNA LAL Banki;Nawabganj RAM NAGAR 1;LAKHRORA;;Uttar Pradesh ;Bara 12 CHANDNI VINOD KUMAR Banki;Ramnagar RAM NAGAR 3;DHAMEDI 3;;Uttar Pradesh ;Bara 13 LALTA PRASAD DESI DEEN Banki;Ramnagar 0;MO. NAYA PURA NAGAR ZAIDPUR PANCHAYAT;;Uttar Pradesh ;Bara 14 VIRENDRA KUMAR BANWARI LAL Banki;Zaidpur RAM NAGAR 1;LAKHRORA;;Uttar Pradesh ;Bara 15 PHULENA GOURAKH Banki;Ramnagar 229;MOULVI KATRA;;Uttar Pradesh ;Bara ZAIDPUR 16 BEWA SHEETLA LATE BARATI LAL Banki;Zaidpur 0;BUDHUGANJ NAYA PURA;;Uttar -

Year IV-Chap.3A-BHAGAVATAM

CHAPTER THREE Krishna in BHAGAVATAM Year IV Chapter 3-BHAGAVATAM BHAGAVATAM Bhagavatam describes the life of Sri Krishna said in the tenth chapter of Bhagavata Purana. The Purana (all eighteen Puranas) is written by Sage Vyasa and is narrated by his son Shukadeva to Pareekshit, the grandson of Arjuna. Balarama (Rama the strong), the elder brother of Sri Krishna is the eighth incarnation and Krishna (one who is dark in complexion), who is very popular, is the ninth incarnation of Lord Vishnu. They were born towards the end of Dwapara yuga to rid the world from the arrogant and unrighteous kings and asuras. (Krishna is the great expounder of the ‘Song Celestial,’ the Bhagavad Gita.) Mother Earth burdened with sinners took refuge in Brahma in the form of a cow. Brahma in turn prayed to Lord Vishnu. In response to the prayers, Vishnu and Adishesha (another aspect of Vishnu; the serpent on which Vishnu rests) incarnated as Krishna and Balarama in the Yadu house, as the sons of Vasudeva & Devaki and all the devas incarnated as their kith and kin to aid them in their mission. KRISHNA and BALARAMA’S BIRTH Vasudeva was a Yadava prince and son of Shura who ruled Shurasena; and Devaki was the niece of King Ugrasena who ruled Mathura. They got married. Later, when Ugrasena’s son Kamsa affectionately took the reins of the couple’s chariot to drive them to the house of Vasudeva, a voice from the heavens said: “O foolish Kamsa, the eighth child of this very woman will slay you.” Furious Kamsa seized Devaki by the hair and raised his sword to bring it down on her. -

2018 NIC BALLIA 8-10-18 (5128).Xlsx

DPR for Ballia, ULB– Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana BLC-(N) (Urban) 2018 WARD S.N CANDIDATE NAME Caste F/H NAME AGE NO. ADDRESS 1 03 AAASHIM KHATOON 4 MAIHARDDIN KURAISHI 43 KAZIPURA ISALAMABAD BALLIA 2 15 AAYASH KHATOON 4 SAKIL AHAMAD 25 RAJENDRA NAGAR ,BALLIA 3 03 ABDUL GAFFAR ANSARI 4 NABBI RASUL 64 KASABTOLA KAJIPURA BALLIA 4 03 ABDUL MAJID 4 ABDUL SAKUR 38 KAZIPURA ISALAMABAD BALLIA 5 03 ABDUL RAHEEM 4 NABI RASOOL 50 KASABTOLA KAJIPURA BALLIA 6 14 ABHAY KUMAR 4 JAYRAM 28 RAJPUT NEWARI,BALLIA 7 11 ABHAY KUMAR YADAV 4 VIJAYMAL YADAV 35 MUHAMMADPUR BALLIA 8 13 ABHISHEK KUUMAR SINGH 4 KASHI NATH SINGH 35 TAIGORE NAGAR JEL KE PEECHE 9 11 ADITYA PRASAD KANU 4 VISHWANATH 66 GANDHI NAGAR CHITBARAGAON 10 11 AFASANA KHATOON 1 YUNUSH ANSHARI 26 BAHERI BALLIA 11 03 AFROJ ALI ANSARI 4 MOHAMMAD GAFFAR 37 KAZIPURA ISALAMABAD BALLIA 12 16 AFTAB ALAM 4 MD. HABIB 45 RAJPUT NEWARI BALLIA 13 03 AJAM KURAISHI 4 HASIM KURASHI 53 KAZIPURA ISALAMABAD BALLIA 14 13 AJAY KUMAR KHARWAR 1 HAR RAM KHARWAR 18 RAMPUR UDDYABHAN NAI BASTI BALLA 15 11 AJAY KUMAR YADAV 4 RAM VILASH YADAV 36 VAJEERAPUR CHANDANPUR BALLIA 16 07 AJAY PASWAN 1 BHARAT PASWAN 31 PURANI BASTI 17 11 AJAY PASWAN 1 SHIV NATH RAM 21 KRISHNA NAGAR, BALLIA 18 11 AJAY YADAV 4 DOMAN YADAV 45 KRISHNA NAGAR KANSHPUR BALLIA 19 13 AJEET KUMAR 4 HARERAM PRASAD 34 RAMPUR UDDYABHAN NAI BASTI BALLA 20 11 AJEET YADAV 4 PARSHURAM YADAV 34 JAPLINGANJ YADAV NAGAR BALLIA 21 03 AKHTAR ALI ANSARI 1 MD JABBAR ASNARI 35 KAZIPURA ISALAMABAD BALLIA 22 03 AKHTAR ALI ANSARI 1 NURUL HASAN 59 KAZIPURA ISLAMABAD BALLILA 23 AKHTARI -

List of Names Drawing Central Samman Pension Sl No

List of Names drawing Central Samman Pension Sl no. Name State ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR 1 MRS. JAMUNA KUMARI ISLANDS 2 BOLLAM NAGALAXMI ANDHRA PRADESH 3 KOMPALLY RADHMMA W/O LATE BAANDHRA PRADESH 4 A HANUMANTHA RAO ANDHRA PRADESH 5 KALYANAPU ANASURYAMMA ANDHRA PRADESH 6 RAMISETTI VENKATA MAHA LAXMI ANDHRA PRADESH 7 LAGADAPATI CHENCHAIAH ANDHRA PRADESH 8 DAMULURI VENKATESWARLU ANDHRA PRADESH 9 N SUBHADRAMMA W/O LATE KOTEANDHRA PRADESH 10 LAGADAPATI KAMALAMMA ANDHRA PRADESH 11 LAGADAPATI NARASIMHA RAO ANDHRA PRADESH 12 LAGADAPATI PAKEERAIAH ANDHRA PRADESH 13 VUNNAM VENKATESWARLU ANDHRA PRADESH 14 VUTUKURU YASODASMMA W/O LATANDHRA PRADESH 15 J BUTCHAIAH ANDHRA PRADESH 16 AKKINENI NIRMALA ANDHRA PRADESH 17 LAGADAPATI NAGESWARA RAO ANDHRA PRADESH 18 YERNENI VENKATA RAVAMMA ANDHRA PRADESH 19 K DHNALAXMI W/O LATE BASAVAIAANDHRA PRADESH 20 RAMISETTI PEDDA VENKATESWARLANDHRA PRADESH 21 KOPPU GOVINDAMMA ANDHRA PRADESH 22 GADDE SATYANARAYANA ANDHRA PRADESH 23 NIRUKONDA KOTESWARA RAO ANDHRA PRADESH 24 KOLLI BHARATHA VENKATA ANDHRA PRADESH 25 GADDE RAGHAVAIAH ANDHRA PRADESH 26 KOTA VENKATA RAVAMMA ANDHRA PRADESH 27 CHIRUMAMILLA SATYANARAYANA ANDHRA PRADESH 28 CHERUKURI KAMALAMMA ANDHRA PRADESH 29 S SUSEELAMMA DEVI W/O LATE SU ANDHRA PRADESH 30 SURYADEVARA V KR MURTHY ANDHRA PRADESH 31 DANTALA SEETHAMMA W/O LATE DANDHRA PRADESH 32 CHAVALA NAGAMMA W/O LATE HAVANDHRA PRADESH 33 SURYADEVARA CHANDRASEKHARAANDHRA PRADESH 34 BAHUDODDA KONDAIAH ANDHRA PRADESH 35 BANDI SATYANARAYANA ANDHRA PRADESH 36 ANUMALA ASWADHA NARAYANA ANDHRA PRADESH 37 KESARI PERAMMA ANDHRA -

Andhra Pradesh

Sl. No. appno rollno name enrollmentno examcity venueaddress 1 venueaddress2 1 44013395 210878 A NEELAKANTESWARA REDDY AP/69/2011 HYDERABAD PENDEKANTI LAW COLLEGE 6th Lane Vivek nagar Chikkadpally 2 430986 211166 A ANJANI DEVI AP/2730/2012 Hyderabad Mahatma Gandhi Law College Beside Ranga Reddy District Court, NTR Nagar LB Nagar 3 416903 211580 A B GIRIRAJ AP/947/2012 Hyderabad Mahatma Gandhi Law College Beside Ranga Reddy District Court, NTR Nagar LB Nagar 4 417049 211990 A BALA RAJESWARI AP/1408/2011 Hyderabad Padala Rama Reddy Law College H No 8-3-724/11 Yella Reddyguda Road,Yusufguda 5 44013988 450052 A CH SEKHARA RAO BANTU AP/1562/2012 Vishakhapatnam N.B.M Law College Gokhale Road Maharanipeta Near American Hospital 6 416589 210977 A CHENNAMMAPUTHRA SRIRAMARYA AP/2356/2012 Hyderabad Mahatma Gandhi Law College Beside Ranga Reddy District Court, NTR Nagar LB Nagar 7 430817 212074 A JAYA PRAKASH RAO AP/1233/2011 Hyderabad Padala Rama Reddy Law College H No 8-3-724/11 Yella Reddyguda Road,Yusufguda 8 416644 210939 A JEEVAN KUMAR AP/2162/2012 Hyderabad Mahatma Gandhi Law College Beside Ranga Reddy District Court, NTR Nagar LB Nagar 9 430949 211612 A KRISHNAIAH AP/2602/2012 Hyderabad Mahatma Gandhi Law College Beside Ranga Reddy District Court, NTR Nagar LB Nagar 10 416134 211927 A MAHIPAL REDDY AP/1931/2010 Hyderabad Padala Rama Reddy Law College H No 8-3-724/11 Yella Reddyguda Road,Yusufguda 11 416942 212025 A OMKARAM AP/1382/2011 Hyderabad Padala Rama Reddy Law College H No 8-3-724/11 Yella Reddyguda Road,Yusufguda 12 417115 211458 A -

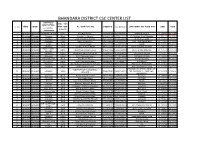

Bhandara District Csc Center List

BHANDARA DISTRICT CSC CENTER LIST ग्रामपंचायत/ झोन / वा셍ड महानगरपाललका Sr. No. जि쥍हा तालुका (फ啍त शहरी कᴂद्र चालक यांचे नाव मोबाईल क्र. CSC-ID/MOL- आपले सरकार सेवा कᴂद्राचा प配ता अ啍ांश रेखांश /नगरपररषद कᴂद्रासाठी) /नगरपंचायत 1 Bhandara Bhandara SHASTRI CHOUK Urban Amit Raju Shahare 9860965355 753215550018 SHASTRI CHOUK 21.177876 79.66254 2 Bhandara Bhandara Bhandara Urban Avinash D. Admane 8208833108 317634110014 Dr. Mukharji Ward,Bhandara 21.1750113 79.65582 3 Bhandara Bhandara Bhandara Urban Jyoti Wamanrao Makode 9371134345 762150550019 NEAR UCO BANK 21.174854 79.64352 4 Bhandara Bhandara Bhandara Urban Sanjiv Gulab Bhure 9595324694 633079050019 CIVIL LINE BHANDARA 21.171533 79.65356 5 Bhandara Bhandara paladi Rural Gulshan Gupta 9423414199 622140700017 paladi 21.169466 79.66144 6 Bhandara Bhandara Bhandara Urban SUJEET N MATURKAR 9970770298 712332740018 RAJIV GANDHI SQUARE 21.1694655 79.66144 RAJIV GANDI 7 Bhandara Bhandara Urban Basant Shivshankar Bisen 9325277936 637272780014 RAJIV GANDI SQUARE 21.167537 79.65599 SQUARE 8 Bhandara Bhandara Bhandara Urban Mohd Wasi Mohd Rafi Sheikh 8830643611 162419790010 RAJENDRA NAGAR 21.16685 79.655364) 9 Bhandara Bhandara Bhandara Urban Kartik Gyaniwant Akare 9326974400 311156120014 IN FRONT OF NH6 21.166096 79.66028 10 Bhandara Bhandara Tekepar[kormbi] Rural Anita Eknath Bhure 9923719175 217736610016 Tekepar[kormbi] 21.1642922 79.65682 11 Bhandara Bhandara BHANDARA Urban Priya Pritamlal Kumbhare 9049025237 114534420013 BHANDARA 21.162895 79.64346 12 Bhandara Bhandara Bhandara Urban Md. Sarfaraz Nawaz Md Shrif Sheikh 8484860484 365824810010 POHA GALI,BHANDARA 21.162768 79.65609 13 Bhandara Bhandara Bhandara Urban Nitesh Natthuji Parate 9579539546 150353710012 Near Bhandara Bus Stop 21.161485 79.65576 FRIENDLY INTERNET ZONE, Z.P TARKESHWAR WASANTRAO 14 Bhandara Bhandara Bhandara Urban 9822359897 434443140013 SQ.