Persistent Political Engagement: Social Interactions and the Dynamics of Protest Movements

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reviewing and Evaluating the Direct Elections to the Legislative Council and the Transformation of Political Parties in Hong Kong, 1991-2016

Journal of US-China Public Administration, August 2016, Vol. 13, No. 8, 499-517 doi: 10.17265/1548-6591/2016.08.001 D DAVID PUBLISHING Reviewing and Evaluating the Direct Elections to the Legislative Council and the Transformation of Political Parties in Hong Kong, 1991-2016 Chung Fun Steven Hung The Education University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong After direct elections were instituted in Hong Kong, politicization inevitably followed democratization. This paper intends to evaluate how political parties’ politics happened in Hong Kong’s recent history. The research was conducted through historical comparative analysis, with the context of Hong Kong during the sovereignty transition and the interim period of democratization being crucial. For the implementation of “one country, two systems”, political democratization was hindered and distinct political scenarios of Hong Kong’s transformation were made. The democratic forces had no alternative but to seek more radicalized politics, which caused a decisive fragmentation of the local political parties where the establishment camp was inevitable and the democratic blocs were split into many more small groups individually. It is harmful. It is not conducive to unity and for the common interests of the publics. This paper explores and evaluates the political history of Hong Kong and the ways in which the limited democratization hinders the progress of Hong Kong’s transformation. Keywords: election politics, historical comparative, ruling, democratization The democratizing element of the Hong Kong political system was bounded within the Legislative Council under the principle of the separation of powers of the three governing branches, Executive, Legislative, and Judicial. Popular elections for the Hong Kong legislature were introduced and implemented for 25 years (1991-2016) and there were eight terms of general elections for the Legislative Council. -

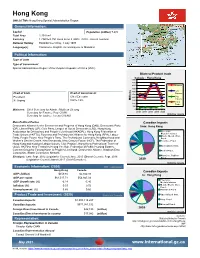

Hong Kong Official Title: Hong Kong Special Administration Region General Information

Hong Kong Official Title: Hong Kong Special Administration Region General Information: Capital Population (million) 7.474n/a Total Area 1,104 km² Currency 1 CAN$=5.791 Hong Kong $ (HKD) (2020 - Annual average) National Holiday Establishment Day, 1 July 1997 Language(s) Cantonese, English, increasing use of Mandarin Political Information: Type of State Type of Government Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China (PRC). Bilateral Product trade Canada - Hong Kong 5000 4500 4000 Balance 3500 3000 Can. Head of State Head of Government Exports 2500 President Chief Executive 2000 Can. Imports XI Jinping Carrie Lam Millions 1500 Total 1000 Trade 500 Ministers: Chief Secretary for Admin.: Matthew Cheung 0 Secretary for Finance: Paul CHAN 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 Statistics Canada Secretary for Justice: Teresa CHENG Main Political Parties Canadian Imports Democratic Alliance for the Betterment and Progress of Hong Kong (DAB), Democratic Party from: Hong Kong (DP), Liberal Party (LP), Civic Party, League of Social Democrats (LSD), Hong Kong Association for Democracy and People’s Livelihood (HKADPL), Hong Kong Federation of Precio us M etals/ stones Trade Unions (HKFTU), Business and Professionals Alliance for Hong Kong (BPA), Labour M ach. M ech. Elec. Party, People Power, New People’s Party, The Professional Commons, Neighbourhood and Prod. Worker’s Service Centre, Neo Democrats, New Century Forum (NCF), The Federation of Textiles Prod. Hong Kong and Kowloon Labour Unions, Civic Passion, Hong Kong Professional Teachers' Union, HK First, New Territories Heung Yee Kuk, Federation of Public Housing Estates, Specialized Inst. Concern Group for Tseung Kwan O People's Livelihood, Democratic Alliance, Kowloon East Food Prod. -

TRANSPORT DEPARTMENT NOTICE Special Traffic and Transport

TRANSPORT DEPARTMENT NOTICE Special Traffic and Transport Arrangements for a Public Event to be held at Victoria Park on 18 August 2019 (Sunday) Notice is hereby given that the following special traffic and transport arrangements will be implemented in the vicinity of Causeway Bay and Tin Hau to facilitate the holding of a public event at Victoria Park on 18 August 2019 (Sunday): (I) Special Traffic Arrangements (A) Road Closure Depending on the prevailing crowd and traffic situation, the following roads may be closed from about 10.30 am onwards until the crowd is dispersed and the road closure is lifted: (i) Sugar Street; (ii) Great George Street; (iii) Kingston Street; (iv) Paterson Street; (v) Cleveland Street; (vi) The section of Gloucester Road northbound between Causeway Road and Gloucester Road service road; (vii) The U-turn slip road leading from Gloucester Road southbound to Gloucester Road northbound underneath Tai Hang Road flyover; (viii) The section of Gloucester Road southbound between Gloucester Road westbound and Causeway Road; (ix) Tai Hang Road flyover; (x) The section of Hing Fat Street between Causeway Road and Lau Li Street (except for franchised buses and green minibuses); (xi) The section of Electric Road between Tsing Fung Street and Hing Fat Street (except for vehicles accessing to Park Towers); (xii) The section of Lau Li Street between Hing Fat Street and Ngan Mok Street (except for vehicles accessing to Park Towers); and (xiii) Yacht Street. (B) Traffic Diversion The following traffic diversion will be implemented -

Editor's Introduction: Activism and Anagnorisis

Old Dominion University ODU Digital Commons English Faculty Publications English 2011 Editor's Introduction: Activism and Anagnorisis Marc Ouellette Old Dominion University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/english_fac_pubs Part of the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons Original Publication Citation Ouellette, M. (2011). Editor's Introduction: Activism and Anagnorisis. Reconstruction: Studies in Contemporary Culture, 11(4). http://reconstruction.digitalodu.com/Issues/114/ouelette_marc.shtml This Editorial is brought to you for free and open access by the English at ODU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of ODU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Current Issues Contributors Past Issues Call for Papers Editorial Board Submissions Search Reconstruction Vol. 11, No. 4 Return to Contents» Activism and Anagnorisis / Marc Ouellette "St. James, often referred to as the "Moor-slayer," is patron saint to veterinarians, equestrians, tanners, furriers, and pharmacists." <1> As I mull the current issue – a wonderful collection of open submissions and a terrific supplement on “post-9/11” developments, about both of which I feel too intellectually impoverished to write adequately – I am filled with mixed feelings, thoughts and even theoretical positions. This last is kind of inescapable given my best efforts to put theory into practice whenever and wherever possible. The two cannot and should not be inseparable, at least for anyone who claims to be even the most remotely involved in Cultural Studies. And yet, I know that this is the area where Cultural Studies fails most abjectly in living up to its claims and to its promise. -

Transport Department Notice

TRANSPORT DEPARTMENT NOTICE SPECIAL TRAFFIC AND TRANSPORT ARRANGEMENTS FOR “HONG KONG ISLAND 10K CITY RACE 2019” Notice is hereby given that special traffic and transport arrangements will be implemented on Hong Kong Island on 8 December 2019 (Sunday) to facilitate the holding of the “Hong Kong Island 10K City Race 2019”: I. TRAFFIC ARRANGEMENTS (Please refer to Plans 1 , 2 & 3) (A) Road Closures Depending on the actual finishing time of the race, and complete clearance for safe re- opening of roads to vehicular traffic, the following roads will be closed to all vehicular traffic at the time specified below (except vehicles with closed road permits): Phase I From about 2.00 am to 10:45 am (i) Convention Avenue between Fleming Road and Tonnochy Road; (ii) Hung Hing Road between Marsh Road and Tonnochy Road; (iii) Harbour Road eastbound between Harbour Drive and Tonnochy Road; (iv) Tonnochy Road between Hung Hing Road and Harbour Road; (v) Tonnochy Road flyover between Harbour Road and Gloucester Road; and (vi) Tonnochy Road southbound between Harbour Road and Gloucester Road. Traffic Diversions: (i) Vehicles on Fleming Road northbound will be prohibited from turning right onto Convention Avenue eastbound, and will be diverted via Lung Wo Road westbound or Expo Drive East northbound; (ii) Vehicles on Fleming Road southbound will be prohibited from turning left onto Harbour Road eastbound; (iii) Vehicles on Harbour Road eastbound must turn left onto Fleming Road northbound; (iv) Vehicles leaving from car parks along Harbour Road eastbound must turn right onto Harbour Road westbound; (v) Vehicles on Harbour Drive northbound must turn left onto Harbour Road westbound; and (vi) Vehicles on Marsh Road northbound will be diverted via Gloucester Road service road or turned onto Marsh Road southbound for access to Jaffe Road. -

Civic Party (Cp)

立法會 CB(2)1335/17-18(04)號文件 LC Paper No. CB(2)1335/17-18(04) CIVIC PARTY (CP) Submission to the United Nations UNIVERSAL PERIODIC REVIEW Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR) CHINA 31st session of the UPR Working Group of the Human Rights Council November 2018 Introduction 1. We are making a stakeholder’s submission in our capacity as a political party of the pro-democracy camp in Hong Kong for the 2018 Universal Periodic Review on the People's Republic of China (PRC), and in particular, the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR). Currently, our party has five members elected to the Hong Kong Legislative Council, the unicameral legislature of HKSAR. 2. In the Universal Periodic Reviews of PRC in 2009 and 2013, not much attention was paid to the human rights, political, and social developments in the HKSAR, whilst some positive comments were reported on the HKSAR situation. i We wish to highlight that there have been substantial changes to the actual implementation of human rights in Hong Kong since the last reviews, which should be pinpointed for assessment in this Universal Periodic Review. In particular, as a pro-democracy political party with members in public office at the Legislative Council (LegCo), we wish to draw the Council’s attention to issues related to the political structure, election methods and operations, and the exercise of freedom and rights within and outside the Legislative Council in HKSAR. Most notably, recent incidents demonstrate that the PRC and HKSAR authorities have not addressed recommendations made by the Human Rights Committee in previous concluding observations in assessing the implementation of International Convention on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR). -

CATC 16Th Meeting

Reference Paper 2 Hong Kong Island 10 km 2018 District Council Consultation Document 1 Aim This consultation document aims to briefly introduce the event preparation, course information and traffic and transportation arrangement of the Hong Kong Island 10km 2018 which the event is organized by Hong Kong Amateur Athletic Association (HKAAA). This event is principally supported by the four District Councils in Hong Kong Island (including Central & Western, Eastern, Southern and Wan Chai District). We hope that we can have fully supported by your District Council. 2 Event Background HKAAA is the member of the International Association of Athletic Federations (IAAF) and Sports Federation & Olympic Committee of Hong Kong, China (SF&OC) has promoted track & field, distance running, race walking and cross country over the past 65 years. The HKAAA is going to organize this 10km road race event again and the route of this event will be similar to last year. 3 Event Information 3.1 Event Date This event is proposed to be held on 9th December 2018 (Sunday). 3.2 Starting Time & Time Limit This event will be started at 7:45am (time limit is two hours) and the estimated reopening time for all closed road will be 11:00am. 3.3 Quota 9,000 participants 3.4 Assembly Venue, Start & Finish Point The Start and the Finish will be located at the Convention Avenue (near the footbridge). Wan Chai Sports Ground will be used as assembly area. Baggage service and toilets will be provided at the Wan Chai Sports Ground. Prize presentation ceremony will also be held at the Wan Chai Sports Ground. -

True Conservative Or Enemy of the Base?

Paul Ryan: True Conservative or Enemy of the Base? An analysis of the Relationship between the Tea Party and the GOP Elmar Frederik van Holten (s0951269) Master Thesis: North American Studies Supervisor: Dr. E.F. van de Bilt Word Count: 53.529 September January 31, 2017. 1 You created this PDF from an application that is not licensed to print to novaPDF printer (http://www.novapdf.com) Page intentionally left blank 2 You created this PDF from an application that is not licensed to print to novaPDF printer (http://www.novapdf.com) Table of Content Table of Content ………………………………………………………………………... p. 3 List of Abbreviations……………………………………………………………………. p. 5 Chapter 1: Introduction…………………………………………………………..... p. 6 Chapter 2: The Rise of the Conservative Movement……………………….. p. 16 Introduction……………………………………………………………………… p. 16 Ayn Rand, William F. Buckley and Barry Goldwater: The Reinvention of Conservatism…………………………………………….... p. 17 Nixon and the Silent Majority………………………………………………….. p. 21 Reagan’s Conservative Coalition………………………………………………. p. 22 Post-Reagan Reaganism: The Presidency of George H.W. Bush……………. p. 25 Clinton and the Gingrich Revolutionaries…………………………………….. p. 28 Chapter 3: The Early Years of a Rising Star..................................................... p. 34 Introduction……………………………………………………………………… p. 34 A Moderate District Electing a True Conservative…………………………… p. 35 Ryan’s First Year in Congress…………………………………………………. p. 38 The Rise of Compassionate Conservatism…………………………………….. p. 41 Domestic Politics under a Foreign Policy Administration……………………. p. 45 The Conservative Dream of a Tax Code Overhaul…………………………… p. 46 Privatizing Entitlements: The Fight over Welfare Reform…………………... p. 52 Leaving Office…………………………………………………………………… p. 57 Chapter 4: Understanding the Tea Party……………………………………… p. 58 Introduction……………………………………………………………………… p. 58 A three legged movement: Grassroots Tea Party organizations……………... p. 59 The Movement’s Deep Story…………………………………………………… p. -

081216-Keast-YAIA-HK

Hong Kong’s disaffected youths – Is the criticism warranted? December 7, 2016 Jacinta Keast Sixtus ‘Baggio’ Leung and Yau Wai-ching, two young legislators from the localist Youngspiration party, have been barred from Hong Kong’s legislative council (LegCo). Never has China’s National People’s Congress (NPC) jumped to an interpretation on a matter in Hong Kong without a prior request from the local government or courts. This comes after the pair modified their oaths, including enunciating the word ‘China’ as ‘Cheena’ (支那), a derogatory term used by the Japanese in World War II, using expletives to refer to the People’s Republic of China, and waving around blue ‘Hong Kong is not China’ banners at their swearing in. Commentators, including those from the pan-democratic side of the legislature, have called their behaviour infantile, ignorant and thuggish, and have demanded ‘that the hooligans be locked up’. But is this criticism warranted? A growing tide of anti-Mainlander vitriol has been building in Hong Kong since it was handed back to the People’s Republic of China in 1997 under a special constitution termed The Basic Law. In theory, the constitution gave Hong Kong special privileges the Mainland did not enjoy—a policy called ‘One Country, Two Systems’. But in practice, more and more Hong Kong residents feel that the long arm of Beijing’s soft power is extending over the territory. The Occupy movement and later the 2014 Umbrella Revolution began once it was revealed that the Chinese government would be pre-screening candidates for the 2017 Hong Kong Chief Executive election, the election for Hong Kong’s top official. -

THE TAX COMPLIANCE IMPLICATIONS of the TEA PARTY MOVEMENT Richard Lavoie*

The University of Akron IdeaExchange@UAkron Akron Law Publications The chooS l of Law October 2011 Patriotism and Taxation: The aT x Compliance Implications of the Tea Party Movement Richard L. Lavoie University of Akron Law School, [email protected] Please take a moment to share how this work helps you through this survey. Your feedback will be important as we plan further development of our repository. Follow this and additional works at: http://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/ua_law_publications Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Lavoie, Richard L., "Patriotism and Taxation: The aT x Compliance Implications of the Tea Party Movement" (2011). Akron Law Publications. 131. http://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/ua_law_publications/131 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by The chooS l of Law at IdeaExchange@UAkron, the institutional repository of The nivU ersity of Akron in Akron, Ohio, USA. It has been accepted for inclusion in Akron Law Publications by an authorized administrator of IdeaExchange@UAkron. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. PATRIOTISM AND TAXATION: THE TAX COMPLIANCE IMPLICATIONS OF THE TEA PARTY MOVEMENT Richard Lavoie* Given the rise of the tea party movement, which draws strength from the historical linkage between patriotism and tax protests in the United States, the role of patriotism as a general tax compliance factor is examined in light of the extant empirical evidence. The existing research suggests that patriotism may be a weaker tax compliance factor in the United States than it is elsewhere. In light of this possibility, the tea party movement has the potential to weaken this compliance factor even more. -

Rival Securitising Attempts in the Democratisation of Hong Kong Written by Neville Chi Hang Li

Rival Securitising Attempts in the Democratisation of Hong Kong Written by Neville Chi Hang Li This PDF is auto-generated for reference only. As such, it may contain some conversion errors and/or missing information. For all formal use please refer to the official version on the website, as linked below. Rival Securitising Attempts in the Democratisation of Hong Kong https://www.e-ir.info/2019/03/29/rival-securitising-attempts-in-the-democratisation-of-hong-kong/ NEVILLE CHI HANG LI, MAR 29 2019 This is an excerpt from New Perspectives on China’s Relations with the World: National, Transnational and International. Get your free copy here. The principle of “one country, two systems” is in grave political danger. According to the Joint Declaration on the Question of Hong Kong signed in 1984, and as later specified in Article 5 of the Basic Law, i.e. the mini-constitution of Hong Kong, the capitalist system and way of life in Hong Kong should remain unchanged for 50 years. This promise not only settled the doubts of the Hong Kong people in the 1980s, but also resolved the confidence crisis of the international community due to the differences in the political and economic systems between Hong Kong and the People’s Republic of China (PRC). As stated in the record of a meeting between Thatcher and Deng in 1982, the Prime Minister regarded the question of Hong Kong as an ‘immediate issue’ as ‘money and skill would immediately begin to leave’ if such political differences were not addressed (Margaret Thatcher Foundation 1982). -

Elevated Walkways Across Harcourt Road and Tim Mei Avenue Gazetted *********************************************************

Elevated walkways across Harcourt Road and Tim Mei Avenue gazetted ********************************************************* The Government published a notice in the Gazette today (November 28) on a proposal to construct two elevated walkways across Harcourt Road and Tim Mei Avenue to meet the future pedestrian demand arising from the Tamar Development Project. Proposed works include an elevated walkway across Harcourt Road connecting Tamar and the footpath adjacent to Admiralty Centre, consisting of a western walkway approximately 5 metres wide and an eastern covered walkway approximately 8 metres wide. The works also involve building a covered elevated walkway approximately 6.5 metres wide across Tim Mei Avenue to connect Tamar and the existing Citic Tower Elevated Walkway System; provision of escalators, staircase and lifts associated with the proposed elevated walkways; and ancillary works such as drainage, landscaping and utility works. Some sections of the existing carriageways, footpaths and amenity areas will be temporarily or permanently closed and reconstructed. The plan and scheme of the works are available for public inspection at the following government offices during office hours: (i) Central and Western District Office, Public Enquiry Service Centre, Unit 5, Ground Floor, The Center, 99 Queen's Road Central; and (ii) District Lands Office, Hong Kong West and South, 20th Floor, Southorn Centre, 130-150 Hennessy Road, Wan Chai. Any person who wishes to object to the proposed works or the use, or both, should write to the Secretary for Transport and Housing, 16th Floor, Murray Building, Garden Road, Hong Kong, on or before January 27, 2009. Ends/Friday, November 28, 2008 .