The Fifteenth-Century Library of Scheyern Abbey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

KW43-2020.Pdf

MITTEILUNGSBLATT FÜR DEN MARKT HOHENWART Jahrgang 43 Freitag, den 23. Oktober 2020 Nr. 43 Der Landtagsabgeordnete Matthias Enghuber besuchte Bürgermeister Jürgen Haindl im Hohenwarter Rathaus. Unser Landtagsabgeordneter Matthias Enghuber hat die Marktgemeinde Hohenwart besucht und sich zum ersten Mal mit Bürgermeister Jürgen Haindl ausgetauscht. Die Auswirkungen der Corona-Pandemie auf die Wirtschaft, und das dadurch ein- geschränkte Vereinsleben waren einer der zu besprechenden Punkte. Weitere wichtige Themen waren die Stärkung des Ehrenamtes und mögliche För- dermittel für den Neubau der Hohenwarter Grund- und Mittelschule Bürgermeister Jürgen Haindl und Landtagsabgeordneter Matthias Enghuber Foto: Markt Hohenwart Hohenwart - 2 - Nr. 43/20 Stellvertretender Landrat Karl Huber ehrte verdiente Feuerwehrleute aus der Marktgemeinde „Es gibt Menschen, die wünschen sich Engagement, es gibt Menschen, die zeigen Engagement und es gibt Menschen, die sind Engagement“, so der Stellvertreter des Landrats Karl Huber bei der Begrüßung der zahlreichen langjährigen Feuerwehrleute bei der Feuerwehrehrung für den südlichen Landkreis Pfaf- fenhofen. Zusammen mit Kreisbrandrat Armin Wiesbeck zeichnete er 48 Feuerwehrfrauen und -männer aus den Gemeinden Gerolsbach, Hohenwart, Jetzendorf, Reichertshausen und Scheyern aus, die der Feuerwehr seit 25 beziehungsweise 40 Jahren angehören. Nach den Worten des Landratsstellvertreters sei bei uns die Feuerwehr ein wesentlicher Bestandteil der ehrenamtlichen Institutionen. Ohne die Freiwilligen Feuerwehren würden -

Vg-Mitteilungen

VG-MITTEILUNGEN Mitteilungsblatt für die Verwaltungsgemeinschaft und die Mitgliedsgemeinden Ilmmünster und Hettenshausen Nr. 12/2020 (38. Jg.) 2. Dezember 2020 „Himmelsbotschaft“ Bild von Susanne Augstburger Wichtige Rufnummern Aktuelles VG Ilmmünster Seniorenadventsfeier beider Gemeinden Freisinger Str. 3, 85304 Ilmmünster abgesagt ..............................................Tel.: 08441/8073-0 Liebe Bürgerinnen und Bürger der Gemeinde .......................................Telefax: 08441/8073-29 Ilmmünster und Hettenshausen, Beiträge für VG-Blatt: ................E-Mail: [email protected] aufgrund der derzeitigen Situation muss leider in beiden Ge- meinden die beliebte Seniorenadventsfeier abgesagt wer- Parteiverkehr: den. Mo., Di., Mi. und Fr. .....................8.00 – 12.00 Uhr Georg Ott (1. Bürgermeister von Ilmmünster) und Wolfgang Donnerstag................................14.00 – 18.00 Uhr Hagl (1. Bürgermeister von Hettenshausen) bedauern dies sehr und wünschen Ihnen trotzdem eine gesunde, fröhliche E-Mail: [email protected] und besinnliche Vorweihnachtszeit. Internetauftritt: www.ilmmünster.de und www.hettenshausen.de Grundschule Ilmmünster Ablesung der Wasserzähler Freisinger Str. 8, 85304 Ilmmünster .................................................Tel.: 08441/2436 Sehr geehrter Abnehmer, .......................................Telefax: 08441/8710930 in Kürze werden wir die Jahresabrechnung für die Verbrauchs- gebühren erstellen. Kindergarten Hettenshausen „Ilmtalmäuse“ Dazu ist die Ablesung -

The Artistic Patronage of Albrecht V and the Creation of Catholic Identity in Sixteenth

The Artistic Patronage of Albrecht V and the Creation of Catholic Identity in Sixteenth- Century Bavaria A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Fine Arts of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Adam R. Gustafson June 2011 © 2011 Adam R. Gustafson All Rights Reserved 2 This dissertation titled The Artistic Patronage of Albrecht V and the Creation of Catholic Identity in Sixteenth- Century Bavaria by ADAM R. GUSTAFSON has been approved for the School of Interdisciplinary Arts and the College of Fine Arts _______________________________________________ Dora Wilson Professor of Music _______________________________________________ Charles A. McWeeny Dean, College of Fine Arts 3 ABSTRACT GUSTAFSON, ADAM R., Ph.D., June 2011, Interdisciplinary Arts The Artistic Patronage of Albrecht V and the Creation of Catholic Identity in Sixteenth- Century Bavaria Director of Dissertation: Dora Wilson Drawing from a number of artistic media, this dissertation is an interdisciplinary approach for understanding how artworks created under the patronage of Albrecht V were used to shape Catholic identity in Bavaria during the establishment of confessional boundaries in late sixteenth-century Europe. This study presents a methodological framework for understanding early modern patronage in which the arts are necessarily viewed as interconnected, and patronage is understood as a complex and often contradictory process that involved all elements of society. First, this study examines the legacy of arts patronage that Albrecht V inherited from his Wittelsbach predecessors and developed during his reign, from 1550-1579. Albrecht V‟s patronage is then divided into three areas: northern princely humanism, traditional religion and sociological propaganda. -

Mission to North America, 1847-1859

Letters of Mary Theresa of Jesus Gerhardinger Volume 1 Sowing the Seed, 1822-1840 Volume 2 Nurturing the Seedling, 1841-1848 Volume 3 Jolted and Joggled, 1849-1852 Volume 4 Vigorous Growth, 1853-1858 Volume 5 Living Branches, 1859-1867 Volume 6 Mission to North America, 1847-1859 Volume 7 Mission to North America, 1860-1879 Volume 8 Mission to Prussia: Brede Volume 9 Mission to Prussia: Breslau Volume 10 Mission to Upper Austria Volume 11 Mission to Baden Mission to Gorizia Volume 12 Mission to Hungary Volume 13 Mission to Austria Mission to England Volume 14 Mission to Tyrol Volume 15 Abundant Fruit, 1868-1879 Letters of Mary Theresa of Jesus Gerhardinger Foundress of the School Sisters of Notre Dame Volume 6 Mission to North America, 1847-1859 Translated, Edited, and Annotated by Mary Ann Kuttner, SSND School Sisters of Notre Dame Printing Department Elm Grove, Wisconsin 2008 Copyright © 2008 by School Sisters of Notre Dame Via della Stazione Aurelia 95 00165 Rome, Italy All rights reserved. Cover Design by Mary Caroline Jakubowski, SSND “All the works of God proceed slowly and in pain; but then, their roots are the sturdier and their flowering the lovelier.” Mary Theresa of Jesus Gerhardinger No. 2277 Contents Preface to Volume 6 ix Introduction xi Chapter 1 April—June 1847 1 Chapter 2 July—August 1847 45 Chapter 3 September—December 1847 95 Chapter 4 1848—1849 141 Chapter 5 1850—1859 177 List of Illustrations 197 List of Documents 199 Index 201 ix Preface to Volume 6 Volume 6 of Letters of Mary Theresa of Jesus Ger- hardinger includes documents from the years 1847 through 1859 that speak of the origins and early development of the mission of the School Sisters of Notre Dame in North Amer- ica. -

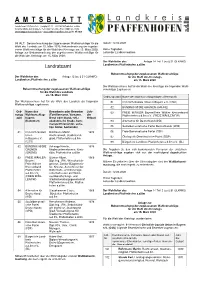

Amtsblatt 05

AMTSBLATT Landratsamt Pfaffenhofen – Hauptplatz 22 – 85276 Pfaffenhofen a.d.Ilm Verantwortlich: Astrid Appel – Tel. 08441/27-394 – Fax: 08441/27-13394 [email protected] - www.landkreis-pfaffenhofen.de Nr. 05/2020 INHALT: Bekanntmachung der zugelassenen Wahlvorschläge für die Datum: 12.02.2020 Wahl des Landrats am 15. März 2020; Bekanntmachung der zugelas- senen Wahlvorschläge für die Wahl des Kreistags am 15. März 2020; Heinz Taglieber, Anlage zur Bekanntmachung der zugelassenen Wahlvorschläge für Leiter der Landkreiswahlen die Wahl des Kreistags am 15. März 2020; _______________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________ Der Wahlleiter des Anlage 14 Teil 1 (zu § 51 GLKrWO) Landkreises Pfaffenhofen a.d.Ilm Landratsamt Bekanntmachung der zugelassenen Wahlvorschläge Der Wahlleiter des Anlage 15 (zu § 51 GLKrWO) für die Wahl des Kreistags Landkreises Pfaffenhofen a.d.Ilm am 15. März 2020 Der Wahlausschuss hat für die Wahl des Kreistags die folgenden Wahl- Bekanntmachung der zugelassenen Wahlvorschläge vorschläge zugelassen: für die Wahl des Landrats am 15. März 2020 Ordnungszahl Name des Wahlvorschlagsträgers (Kennwort) Der Wahlausschuss hat für die Wahl des Landrats die folgenden 01 Christlich-Soziale Union in Bayern e.V. (CSU) Wahlvorschläge zugelassen: 02 BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN (GRÜNE) Ord- Name des Bewerberin oder Bewerber Jahr 03 FREIE WÄHLER Bayern/Freie Wähler Kreisverband nungs Wahlvorschlag- (Familienname, Vorname, der Pfaffenhofen a.d.Ilm e.V. (FREIE WÄHLER/FW) zahl trägers Beruf oder Stand, evtl.: Geburt (Kennwort) akademische Grade, kom- 04 Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) munale Ehrenämter, sons- tige Ämter, Gemeinde) 05 Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands (SPD) 01 Christlich-Soziale Rohrmann Martin, 1972 06 Freie Demokratische Partei (FDP) Union Rechtsanwalt, Stadtratsmit- 07 Ökologisch-Demokratische Partei (ÖDP) in Bayern e.V. -

Bearings, We Look for Clues About the Future of the Church by Paying Attention to the Church of the Present

for the Life of Faith A UTUMN 2013 A Publication of the Collegeville Institute for Ecumenical and Cultural Research Editors’ Note Theologian James Gustafson once referred to the church as housing “treasure in earthen vessels.” Treasure may abide, but earthenware is notoriously apt to chip, crack, and shatter. It’s an appropriate image for our time. Far and wide, scholars are diagnosing a permanent state of decline in the institutional church as we know it, at least in the West. According to nearly every marker of institutional health, the church is failing. It is bitterly divided, financially strapped, plagued by abuses of power, shrinking in numbers, and poorly regarded in public perception. Tellingly, a growing number of prominent Christian figures are quite willing to bid farewell to the church—the very institution that reared them and upon which their livelihood depends. With titles such as Jesus for the Non-Religious, Saving Jesus from the Church, and Christianity After Religion, various church leaders are suggesting that the church may be more of a hindrance than a help to Christian identity and mission in today’s context. It’s hard not to hear echoes of theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer who, over 75 years ago, warned in his book The Cost of Discipleship of a church “overlaid with so much human ballast—burdensome rules and regulations, false hopes and consola- tions,” that it stood in danger of abandoning its central call to follow the way of Jesus. Even if the church is coming to some sort of an end, Christianity is still very much with us. -

Index of Manuscripts

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-13698-4 — The European Book in the Twelfth Century Edited by Erik Kwakkel , Rodney Thomson Index More Information Index of Manuscripts Aberystwyth, National Libr. of Wales 17110B II 2425 41 (‘Book of Llandaff’) 21, 314 8486–91 266 Peniarth 540 314 Admont, Stiftsbibl. 434 41 Cambrai, Médiathèque mun. 168 274 742 235 Cambridge Angers, Bibl. mun. 304 (295) 323 Corpus Christi Coll. 2 (‘Bury Bible’) 10, 13, 49, Assisi, Bibl. del sacro conv. 573 222–3, 232, 236 Fig. 3.3, 57, 83 Avesnes, Société Archéologique, s. n. 49 3–4 (‘Dover Bible’) 46, 49 Avranches, Bibl. mun. 72 58 Fitzwilliam Museum 24 13 91 41 Maclean 165 232 128 73 Gonville & Caius Coll. 2/224 229 234 3/324 6/624 Bamberg, Staatsbibl. Class. 10 234 7/724 Class. 15 220, 232 10/10 24 Class. 21 248 12/128 24 Patr. 511, 19, 74 14/130 24 Barcelona, Archivo de la Corona de Aragón, 15/131 24 Ripoll 78 310 16/132 24 Basel, Universitätsbibl. N I 2, 83 323 17/133 24 Beirut, Université de St Joseph 223 275 18/134 24 Berlin, Staatsbibl. germ. fol. 282 63 19/135 24 lat. fol. 74 263 123/60 320 lat. fol. 252 245 427/427 36 lat. fol. 272 302 456/394 275 lat. fol. 273 301–2 Jesus Coll. Q. D. 2 (44) 266, 321 lat. qu. 198 283–6 Pembroke Coll. 59 169 Phillipps 1925 322 113 320 Bern, Burgerbibl. 79 322 Peterhouse 229 23 120 63 St John’s Coll. -

Lindau, Germany and Take Your Bike on the Ferry to Rorschach, Switzerland

english Bodensee! LAKE CONSTANCE TRAVEL GUIDE One Lake. Four Countries. All Year Round. BODENSEE MAP INCLUDED HIGHLIGHTS EVENTS INSPIRATION www.bodensee.eu WELCOME Follow us on Instagram: bodensee.eu Share your Bodensee experiences by using the hashtag #bodensee4u © www.bayern.com | Gert Krautbauer © www.bayern.com CONTENT Bodensee passenger ships © Schaffhauserland Tourismus Dörflingen Rhine Welcome ................................................................................................... 3 Seasons .................................................................................................... 4 Must-Do .................................................................................................... 6 WELCOME TO THE Event Highlights ...................................................................................... 8 Four Countries ....................................................................................... 10 Bodensee Cities .................................................................................... 12 BODENSEE! Culinary Delights .................................................................................. 16 INFORMATION Bodensee Region – Unique in the World! Culture .................................................................................................... 20 Tourist Board of Lake Constance Active and nature ................................................................................. 24 Hafenstraße 6, 78462 Constance (Germany) Water ...................................................................................................... -

Application of Link Integrity Techniques from Hypermedia to the Semantic Web

UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON Faculty of Engineering and Applied Science Department of Electronics and Computer Science A mini-thesis submitted for transfer from MPhil to PhD Supervisor: Prof. Wendy Hall and Dr Les Carr Examiner: Dr Nick Gibbins Application of Link Integrity techniques from Hypermedia to the Semantic Web by Rob Vesse February 10, 2011 UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON ABSTRACT FACULTY OF ENGINEERING AND APPLIED SCIENCE DEPARTMENT OF ELECTRONICS AND COMPUTER SCIENCE A mini-thesis submitted for transfer from MPhil to PhD by Rob Vesse As the Web of Linked Data expands it will become increasingly important to preserve data and links such that the data remains available and usable. In this work I present a method for locating linked data to preserve which functions even when the URI the user wishes to preserve does not resolve (i.e. is broken/not RDF) and an application for monitoring and preserving the data. This work is based upon the principle of adapting ideas from hypermedia link integrity in order to apply them to the Semantic Web. Contents 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Hypothesis . .2 1.2 Report Overview . .8 2 Literature Review 9 2.1 Problems in Link Integrity . .9 2.1.1 The `Dangling-Link' Problem . .9 2.1.2 The Editing Problem . 10 2.1.3 URI Identity & Meaning . 10 2.1.4 The Coreference Problem . 11 2.2 Hypermedia . 11 2.2.1 Early Hypermedia . 11 2.2.1.1 Halasz's 7 Issues . 12 2.2.2 Open Hypermedia . 14 2.2.2.1 Dexter Model . 14 2.2.3 The World Wide Web . -

Monastic Reform and Autobiographical Dialogue: the Senatorium of Abbot Martin of Leibitz

MONASTIC REFORM AND AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL DIALOGUE: THE SENATORIUM OF ABBOT MARTIN OF LEIBITZ Harald Tersch Universität Wien [email protected] orcid.org/0000-0003-1800-8679 Recepción: 08-01-2016 / Aceptación: 22-11-2016 Abstract T e autobiographical dialogue is based upon the principle of questioning the fundamentals of one’s own life script and off ered itself in particular during times of reform movements, when role models and values within communities were open to debate. T e monastic reforms of the 14th and 15th centuries created a new authority with the category of Visitors who frequently did not advance accord- ing to the hierarchy of the monastery visited, but instead entered them laterally, in order to ensure the long-term success of the arrangements. T is authority to exert power increased the need for justifi cation. In his Senatorium the Benedic- tine reform abbot and Visitor Martin of Leibitz/L’ubica (1400-1464) legitimized his self-refl ection with the claim to a didactic conversation in the tradition of the Gregorian Dialogues, the Bohemian Malogranatum and the Formicarius of Johannes Nider. T e dialogue relates the conversation between a youth and an old man. T e elderly man (senex) is Martin’s “alter ego” who wishes to speak of his experience according to the classical stages of life, the young man represents an inquisitive cue-giver who challenges his partner by agreement or contradic- tion. T e autobiography suggests the atmosphere of a chapter hall. It is drawn on the modus of an inquisitio and fi lled with contemporary possibilities for mo- nastic self-thematization in interviews, visitiation reports or letters. -

Convert Finding Aid To

The Popular Imagery Collection An Inventory of the Collection at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Title: Popular Imagery Collection Dates: circa 14th–19th centuries (bulk 16th–18th centuries) Extent: 22 boxes, 3 flat file drawers, 2 rolled prints, 1 large folder (822 items) Abstract: The Popular Imagery collection comprises 822 European prints, paintings, and drawings, most of which date from the 16th through 18th centuries. Language: Almost half of the works have German titles and/or text; other predominant languages are French, Latin, Dutch, and Italian. There are a few works with English or Spanish text. Access: Open for research. A minimum of twenty-four hours is required to pull art materials to the Reading Room. Digital images from this collection are available on the ArtStor website. Administrative Information Acquisition: Purchase (R1775, R1776, R1777) 1963 Processed by: Helen Young, 2004 Repository: The University of Texas at Austin, Harry Ransom Center Sources: For additional information, see “Popular Imagery” by Norman Farmer, Jr., in The Library Chronicle, N.S. no.4 (1972): 49-57. Scope and Contents The Popular Imagery collection comprises 822 European prints, paintings, and drawings, most of which date from the 16th through 18th centuries. Prints make up the bulk of the collection, with 686 intaglios (including seventeen mezzotints), 115 woodcuts, one wood engraving, and six lithographs. There are fourteen unique drawings and paintings. Six of the works are on vellum, and there is an engraving on silk. In addition there are four sheets of accompanying letterpress. Almost half of the works have German titles and/or text; other predominant languages are French, Latin, Dutch, and Italian. -

Sowing the Seed, 1822-1840

Letters of Mary Theresa of Jesus Gerhardinger Volume 1 Sowing the Seed, 1822-1840 Volume 2 Nurturing the Seedling, 1841-1848 Volume 3 Jolted and Joggled, 1849-1852 Volume 4 Vigorous Growth, 1853-1858 Volume 5 Living Branches, 1859-1867 Volume 6 Mission to North America, 1847-1859 Volume 7 Mission to North America, 1860-1879 Volume 8 Mission to Prussia: Brede Volume 9 Mission to Prussia: Breslau Volume 10 Mission to Upper Austria Volume 11 Mission to Baden Mission to Gorizia Volume 12 Mission to Hungary Volume 13 Mission to Austria Mission to England Volume 14 Mission to Tyrol Volume 15 Abundant Fruit, 1868-1879 Letters of Mary Theresa of Jesus Gerhardinger Foundress of the School Sisters of Notre Dame Volume 1 Sowing the Seed 1822—1840 Translated, Edited, and Annotated by Mary Ann Kuttner, SSND School Sisters of Notre Dame Printing Department Elm Grove, Wisconsin 2010 Copyright © 2010 by School Sisters of Notre Dame Via della Stazione Aurelia 95 00165 Rome, Italy All rights reserved. Cover Design by Mary Caroline Jakubowski, SSND “All the works of God proceed slowly and in pain; but then, their roots are the sturdier and their flowering the lovelier.” Mary Theresa of Jesus Gerhardinger No. 2277 Contents Letter from Mary V. Maher, SSND ix Foreword by Rosemary Howarth, SSND xiii Preface xv Acknowledgments xix Chronology xxi Preface to Volume 1 xxv Introduction to Volume 1 xxvii Chapter 1 1822—1832 1 Chapter 2 1833—1834 27 Chapter 3 1835 57 Chapter 4 1836 71 Chapter 5 1837 105 Chapter 6 1838 117 Chapter 7 1839 147 Chapter 8 1840 175 List of Documents 209 Index 213 Mary Theresa of Jesus Gerhardinger (1797-1879) Illustration by Norbert Schinkmann, 1996.