Chapter 7 – Flood Hazards: Risks and Mitigation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

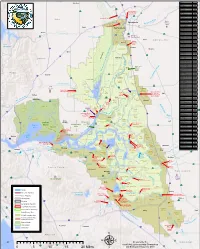

0 5 10 15 20 Miles Μ and Statewide Resources Office

Woodland RD Name RD Number Atlas Tract 2126 5 !"#$ Bacon Island 2028 !"#$80 Bethel Island BIMID Bishop Tract 2042 16 ·|}þ Bixler Tract 2121 Lovdal Boggs Tract 0404 ·|}þ113 District Sacramento River at I Street Bridge Bouldin Island 0756 80 Gaging Station )*+,- Brack Tract 2033 Bradford Island 2059 ·|}þ160 Brannan-Andrus BALMD Lovdal 50 Byron Tract 0800 Sacramento Weir District ¤£ r Cache Haas Area 2098 Y o l o ive Canal Ranch 2086 R Mather Can-Can/Greenhead 2139 Sacramento ican mer Air Force Chadbourne 2034 A Base Coney Island 2117 Port of Dead Horse Island 2111 Sacramento ¤£50 Davis !"#$80 Denverton Slough 2134 West Sacramento Drexler Tract Drexler Dutch Slough 2137 West Egbert Tract 0536 Winters Sacramento Ehrheardt Club 0813 Putah Creek ·|}þ160 ·|}þ16 Empire Tract 2029 ·|}þ84 Fabian Tract 0773 Sacramento Fay Island 2113 ·|}þ128 South Fork Putah Creek Executive Airport Frost Lake 2129 haven s Lake Green d n Glanville 1002 a l r Florin e h Glide District 0765 t S a c r a m e n t o e N Glide EBMUD Grand Island 0003 District Pocket Freeport Grizzly West 2136 Lake Intake Hastings Tract 2060 l Holland Tract 2025 Berryessa e n Holt Station 2116 n Freeport 505 h Honker Bay 2130 %&'( a g strict Elk Grove u Lisbon Di Hotchkiss Tract 0799 h lo S C Jersey Island 0830 Babe l Dixon p s i Kasson District 2085 s h a King Island 2044 S p Libby Mcneil 0369 y r !"#$5 ·|}þ99 B e !"#$80 t Liberty Island 2093 o l a Lisbon District 0307 o Clarksburg Y W l a Little Egbert Tract 2084 S o l a n o n p a r C Little Holland Tract 2120 e in e a e M Little Mandeville -

The Arkstorm Scenario: California's Other "Big One"

The San Bernardino County Museum Guest Lecture Series The ARkStorm Scenario: California’s other “Big One” Lucy Jones • U. S. Geological Survey Wednesday, January 25, 2012 • 7:30pm • Free Admission Landslides and debris flows. Coastal innundation and flooding. Infrastructure damage. Pollution. Dr. Lucy Jones will give an overview of the ARkStorm Scenario—catastrophic flooding resulting from a month-long deluge like was seen in 1862, and four larger such events in the past 100 years. This type of storm, resulting from atmospheric rivers of moisture, is plausible, and a smaller version hit San Bernardino in December of 2010 with a week’s worth of rain that impacted Highland and the surrounding communities. The ARkStorm Scenario explores the resulting impacts to our social structure and can be used to understand how California’s “other” Big One can be more expensive than a large San Andreas earthquake. Dr. Lucy Jones has been a seismologist with the US Geological Survey and a Visiting Research Associate at the Seismological Laboratory of Caltech since 1983. She currently serves as the Science Advisor for the Natural Hazards Mission of the US Geological Survey, leading the long-term science planning for natural hazards research. She also leads the SAFRR Project: Science Application for Risk Reduction to apply USGS science to reduce risk in communities across the nation. Dr. Jones has written more than 90 papers on research seismology with primary interest in the physics of earthquakes, foreshocks, and earthquake hazard assessment, especially in southern California. She serves on the California Earthquake Prediction Evaluation Council and was a Commissioner of the California Seismic Safety Commission from 2002 to 2009. -

Transitions for the Delta Economy

Transitions for the Delta Economy January 2012 Josué Medellín-Azuara, Ellen Hanak, Richard Howitt, and Jay Lund with research support from Molly Ferrell, Katherine Kramer, Michelle Lent, Davin Reed, and Elizabeth Stryjewski Supported with funding from the Watershed Sciences Center, University of California, Davis Summary The Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta consists of some 737,000 acres of low-lying lands and channels at the confluence of the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers (Figure S1). This region lies at the very heart of California’s water policy debates, transporting vast flows of water from northern and eastern California to farming and population centers in the western and southern parts of the state. This critical water supply system is threatened by the likelihood that a large earthquake or other natural disaster could inflict catastrophic damage on its fragile levees, sending salt water toward the pumps at its southern edge. In another area of concern, water exports are currently under restriction while regulators and the courts seek to improve conditions for imperiled native fish. Leading policy proposals to address these issues include improvements in land and water management to benefit native species, and the development of a “dual conveyance” system for water exports, in which a new seismically resistant canal or tunnel would convey a portion of water supplies under or around the Delta instead of through the Delta’s channels. This focus on the Delta has caused considerable concern within the Delta itself, where residents and local governments have worried that changes in water supply and environmental management could harm the region’s economy and residents. -

Hurricane Flooding

ATM 10 Severe and Unusual Weather Prof. Richard Grotjahn L 18/19 http://canvas.ucdavis.edu Lecture 18 topics: • Hurricanes – what is a hurricane – what conditions favor their formation? – what is the internal hurricane structure? – where do they occur? – why are they important? – when are those conditions met? – what are they called? – What are their life stages? – What does the ranking mean? – What causes the damage? Time lapse of the – (Reading) Some notorious storms 2005 Hurricane Season – How to stay safe? Note the water temperature • Video clips (colors) change behind hurricanes (black tracks) (Hurricane-2005_summer_clouds-SST.mpg) Reading: Notorious Storms • Atlantic hurricanes are referred to by name. – Why? • Notorious storms have their name ‘retired’ © AFP Notorious storms: progress and setbacks • August-September 1900 Galveston, Texas: 8,000 dead, the deadliest in U.S. history. • September 1906 Hong Kong: 10,000 dead. • September 1928 South Florida: 1,836 dead. • September 1959 Central Japan: 4,466 dead. • August 1969 Hurricane Camille, Southeast U.S.: 256 dead. • November 1970 Bangladesh: 300,000 dead. • April 1991 Bangladesh: 70,000 dead. • August 1992 Hurricane Andrew, Florida and Louisiana: 24 dead, $25 billion in damage. • October/November 1998 Hurricane Mitch, Honduras: ~20,000 dead. • August 2005 Hurricane Katrina, FL, AL, MS, LA: >1800 dead, >$133 billion in damage • May 2008 Tropical Cyclone Nargis, Burma (Myanmar): >146,000 dead. Some Notorious (Atlantic) Storms Tracks • Camille • Gilbert • Mitch • Andrew • Not shown: – 2004 season (Charley, Frances, Ivan, Jeanne) – Katrina (Wilma & Rita) (2005) – Sandy (2012), Harvey (2017), Florence & Michael (2018) Hurricane Camille • 14-19 August 1969 • Category 5 at landfall – for 24 hours – peak winds 165 kts (190mph @ landfall) – winds >155kts for 18 hrs – min SLP 905 mb (26.73”) – 143 perished along gulf coast, – another 113 in Virginia Hurricane Andrew • 23-26 August 1992 • Category 5 at landfall • first Category 5 to hit US since Camille • affected S. -

Imaging Laurentide Ice Sheet Drainage Into the Deep Sea: Impact on Sediments and Bottom Water

Imaging Laurentide Ice Sheet Drainage into the Deep Sea: Impact on Sediments and Bottom Water Reinhard Hesse*, Ingo Klaucke, Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec H3A 2A7, Canada William B. F. Ryan, Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory of Columbia University, Palisades, NY 10964-8000 Margo B. Edwards, Hawaii Institute of Geophysics and Planetology, University of Hawaii, Honolulu, HI 96822 David J. W. Piper, Geological Survey of Canada—Atlantic, Bedford Institute of Oceanography, Dartmouth, Nova Scotia B2Y 4A2, Canada NAMOC Study Group† ABSTRACT the western Atlantic, some 5000 to 6000 State-of-the-art sidescan-sonar imagery provides a bird’s-eye view of the giant km from their source. submarine drainage system of the Northwest Atlantic Mid-Ocean Channel Drainage of the ice sheet involved (NAMOC) in the Labrador Sea and reveals the far-reaching effects of drainage of the repeated collapse of the ice dome over Pleistocene Laurentide Ice Sheet into the deep sea. Two large-scale depositional Hudson Bay, releasing vast numbers of ice- systems resulting from this drainage, one mud dominated and the other sand bergs from the Hudson Strait ice stream in dominated, are juxtaposed. The mud-dominated system is associated with the short time spans. The repeat interval was meandering NAMOC, whereas the sand-dominated one forms a giant submarine on the order of 104 yr. These dramatic ice- braid plain, which onlaps the eastern NAMOC levee. This dichotomy is the result of rafting events, named Heinrich events grain-size separation on an enormous scale, induced by ice-margin sifting off the (Broecker et al., 1992), occurred through- Hudson Strait outlet. -

Spatial Variability of Levees As Measured Using the CPT

2nd International Symposium on Cone Penetration Testing, Huntington Beach, CA, USA, May 2010 Spatial Variability of Levees as Measured Using the CPT R.E.S. Moss Assistant Professor, Cal Poly, San Luis Obispo J. C. Hollenback Graduate Researcher, U.C. Berkeley J. Ng Undergraduate Researcher, Cal Poly, San Luis Obispo ABSTRACT: The spatial variability of a soil deposit is something that is commonly discussed but difficult to quantify. The heterogeneity as a function of lateral distance can be critical to the design of long engineered structures such as highways, bridges, levees, and other lifelines. This paper presents a methodology for using CPT mea- surements to quantifying the spatial variability of cone tip resistance along a levee in the California Bay Delta. The results, presented in the form of a general relative va- riogram, identify the distance at which the maximum spatial variability is achieved for a given soil strata. This information helps define minimally correlated stretches of levee for proper failure and risk analysis. Presented herein are methods of interpret- ing, calculating, and analyzing CPT data to arrive at the quantified spatial variability with respect to different static and seismic failure modes common to levee systems. 1 INTRODUCTION Spatial variability of engineering properties in soil strata is inherent to the nature of soil. Spatial variability is controlled primarily by the depositional environment where high energy systems usually deposit materials with high spatial variability (e.g. al- luvial gravels) and low energy systems usually deposit materials with low spatial va- riability (e.g. lacustrine clays). This spatial variability is generally taken into account in geotechnical design in a qualitative empirical manner through appropriately spaced borings to assess the changing subsurface conditions. -

A Policy Response to the Water Supply and Flood Control in Changing Climate

Capstone Project A Policy Response to the Water Supply and Flood Control in Changing Climate Nataliia Zadorkina Scripps Institution of Oceanography University of California San Diego June, 2016 1 Table of Contents: Executive Summary……………………………………………………………………… 3 Policy Brief………………………………………………………………………………. 5 References………………………………………………………………………………… 16 Appendix…………………………………………………………………………………. 19 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY CAPSTONE SUBJECT: The Policy Response to Water Supply and Flood Control in Changing Climate CAPSTONE DELIVERABLE: Policy Brief “Recommendations on executive actions on the water supply and flood control” AUDIENCE: California Department of Water Resources ALIGNMENT WITH CLIMATE SCEINCE & POLICY: climate science – the link between climate change and extreme weather events, the role of atmospheric rivers in water supply and flood control; policy – recommendations on supporting scientific research targeting fulfilling informational gaps which will foster more reliable weather forecasting with an ultimate goal to be prepared for uncertainties associated with climate change effect on water availability and, subsequently, on reservoir operations. APPLICATION: The project has a direct effect on policy associated with climate change adaptation. The findings to be presented on the North Coast Regional Water Quality Control Board (RWQCB) meeting on June 16, 2016 in Santa Rosa, CA as well as on the Sonoma County Grape Growers board meeting in Petaluma, CA. In hindsight, what used to be a highly polarized topic within the scientific community, the consensus behind man-made climate change has become increasingly uniform. In 2014, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) released a ‘Fifth Assessment’ report citing “unequivocal” evidence of rising average air and ocean temperatures (Graphic 1). Graphic 1: Temperature and Precipitation at Santa Rosa, CA, from 1890 to 2014 (Data source: National Climatic Data Center, NOAA). -

Part 629 – Glossary of Landform and Geologic Terms

Title 430 – National Soil Survey Handbook Part 629 – Glossary of Landform and Geologic Terms Subpart A – General Information 629.0 Definition and Purpose This glossary provides the NCSS soil survey program, soil scientists, and natural resource specialists with landform, geologic, and related terms and their definitions to— (1) Improve soil landscape description with a standard, single source landform and geologic glossary. (2) Enhance geomorphic content and clarity of soil map unit descriptions by use of accurate, defined terms. (3) Establish consistent geomorphic term usage in soil science and the National Cooperative Soil Survey (NCSS). (4) Provide standard geomorphic definitions for databases and soil survey technical publications. (5) Train soil scientists and related professionals in soils as landscape and geomorphic entities. 629.1 Responsibilities This glossary serves as the official NCSS reference for landform, geologic, and related terms. The staff of the National Soil Survey Center, located in Lincoln, NE, is responsible for maintaining and updating this glossary. Soil Science Division staff and NCSS participants are encouraged to propose additions and changes to the glossary for use in pedon descriptions, soil map unit descriptions, and soil survey publications. The Glossary of Geology (GG, 2005) serves as a major source for many glossary terms. The American Geologic Institute (AGI) granted the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service (formerly the Soil Conservation Service) permission (in letters dated September 11, 1985, and September 22, 1993) to use existing definitions. Sources of, and modifications to, original definitions are explained immediately below. 629.2 Definitions A. Reference Codes Sources from which definitions were taken, whole or in part, are identified by a code (e.g., GG) following each definition. -

Presentation

Severe Weather in North America Peter Hoeppe, Head Geo Risks Research/Corporate Climate Centre, Munich Re ECSS 2013, Helsinki, June 3, 2013 US Insurance Survey April 2013 Participants: 81 CEOs of US Primary Insurers What are the 3 most critical issues facing the primary insurance industry today? Issue Rank Low interest rates and capital market returns 1st (64%) Natural catastrophes/weather events 2nd (51%) Price competition 3rd (43%) Multiple responses allowed. Does not add to 100%. MR NatCatSERVICE The world‘s largest database on natural catastrophes The Database Today . From 1980 until today all loss events; for USA and selected countries in Europe all loss events since 1970. Retrospectively, all great disasters since 1950. In addition, all major historical events starting from 79 AD – eruption of Mt. Vesuvius (3,000 historical data sets). Currently more than 32,000 data sets 3 NatCatSERVICE Weather catastrophes worldwide 1980 – 2012 Percentage distribution – ordered by continent 18,200 Loss events 1,405,000 Fatalities 4% <1% 1% 8% 25% 11% 30% 41% 6% 43% 9% 22% Overall losses* US$ 2,800bn Insured losses* US$ 855bn 3% 3% 9% 31% 46% 18% 1% 16% 70% 3% *in 2012 values *in 2012 values Africa Asia Australia/Oceania Europe North America, South America incl. Central America and Caribbean © 2013 Münchener Rückversicherungs-Gesellschaft, Geo Risks Research, NatCatSERVICE – As at January 2013 Global Natural Catastrophe Update Natural catastrophes worldwide 2012 Insured losses US$ 65bn - Percentage distribution per continent 5% 91% <3% <1% <1% Continent -

Transitions for the Delta Economy

Transitions for the Delta Economy January 2012 Josué Medellín-Azuara, Ellen Hanak, Richard Howitt, and Jay Lund with research support from Molly Ferrell, Katherine Kramer, Michelle Lent, Davin Reed, and Elizabeth Stryjewski Supported with funding from the Watershed Sciences Center, University of California, Davis Summary The Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta consists of some 737,000 acres of low-lying lands and channels at the confluence of the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers (Figure S1). This region lies at the very heart of California’s water policy debates, transporting vast flows of water from northern and eastern California to farming and population centers in the western and southern parts of the state. This critical water supply system is threatened by the likelihood that a large earthquake or other natural disaster could inflict catastrophic damage on its fragile levees, sending salt water toward the pumps at its southern edge. In another area of concern, water exports are currently under restriction while regulators and the courts seek to improve conditions for imperiled native fish. Leading policy proposals to address these issues include improvements in land and water management to benefit native species, and the development of a “dual conveyance” system for water exports, in which a new seismically resistant canal or tunnel would convey a portion of water supplies under or around the Delta instead of through the Delta’s channels. This focus on the Delta has caused considerable concern within the Delta itself, where residents and local governments have worried that changes in water supply and environmental management could harm the region’s economy and residents. -

Bear Creek Watershed Assessment Report

BEAR CREEK WATERSHED ASSESSMENT PLACER COUNTY, CALIFORNIA Prepared for: Prepared by: PO Box 8568 Truckee, California 96162 February 16, 2018 And Dr. Susan Lindstrom, PhD BEAR CREEK WATERSHED ASSESSMENT – PLACER COUNTY – CALIFORNIA February 16, 2018 A REPORT PREPARED FOR: Truckee River Watershed Council PO Box 8568 Truckee, California 96161 (530) 550-8760 www.truckeeriverwc.org by Brian Hastings Balance Hydrologics Geomorphologist Matt Wacker HT Harvey and Associates Restoration Ecologist Reviewed by: David Shaw Balance Hydrologics Principal Hydrologist © 2018 Balance Hydrologics, Inc. Project Assignment: 217121 800 Bancroft Way, Suite 101 ~ Berkeley, California 94710-2251 ~ (510) 704-1000 ~ [email protected] Balance Hydrologics, Inc. i BEAR CREEK WATERSHED ASSESSMENT – PLACER COUNTY – CALIFORNIA < This page intentionally left blank > ii Balance Hydrologics, Inc. BEAR CREEK WATERSHED ASSESSMENT – PLACER COUNTY – CALIFORNIA TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Project Goals and Objectives 1 1.2 Structure of This Report 4 1.3 Acknowledgments 4 1.4 Work Conducted 5 2 BACKGROUND 6 2.1 Truckee River Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) 6 2.2 Water Resource Regulations Specific to Bear Creek 7 3 WATERSHED SETTING 9 3.1 Watershed Geology 13 3.1.1 Bedrock Geology and Structure 17 3.1.2 Glaciation 18 3.2 Hydrologic Soil Groups 19 3.3 Hydrology and Climate 24 3.3.1 Hydrology 24 3.3.2 Climate 24 3.3.3 Climate Variability: Wet and Dry Periods 24 3.3.4 Climate Change 33 3.4 Bear Creek Water Quality 33 3.4.1 Review of Available Water Quality Data 33 3.5 Sediment Transport 39 3.6 Biological Resources 40 3.6.1 Land Cover and Vegetation Communities 40 3.6.2 Invasive Species 53 3.6.3 Wildfire 53 3.6.4 General Wildlife 57 3.6.5 Special-Status Species 59 3.7 Disturbance History 74 3.7.1 Livestock Grazing 74 3.7.2 Logging 74 3.7.3 Roads and Ski Area Development 76 4 WATERSHED CONDITION 81 4.1 Stream, Riparian, and Meadow Corridor Assessment 81 Balance Hydrologics, Inc. -

Constructing

Constructing Mimi Hughes (NOAA), Tapash Das (SIO), Dale Cox (USGS) Multi-Hazards Demonstration Project • Fire / Debris Flow 2007 Post Fire Coordination • Earthquake / Tsunami Earthquake Scenario • Winter Storm Winter Storm Scenario • Information Interface Community Interface, Implementation, Tools and Training The Great Southern California ShakeOut • A week-long series of events to inspire southern Californians to improve their earthquake resiliency; >6 million participants • Based on a scenario of a major southern San Andreas earthquake designed by the USGS for California Office of Homeland Security’s Golden Guardian exercise, Nov 2008, Oct 2009, Oct 2010, … • December 24, 1861 through Jan 21, 1862: nearly unbroken rains • Central Valley flooding over about 300 mi long, 12 – 60 mi wide • Most of LA basin reported as “generally inundated” • San Gabriel & San Diego Rivers cut new paths to sea • 420% of normal-January precipitation in Sacramento in Jan 1862 • 300% of normal-January precipitation fell in K Street Sacramento, looking east San Diego in Jan 1862 • No way of knowing how intense the rains were, but they were exceptionally large in total and prolonged. • Implication: Prolonged storm episodes are a plausible mechanism for winter-storm disaster conditions in California • Implication: A combined NorCal+SoCal extreme event is plausible. 12 days separated the flood crest in Sacramento from the crest in Los Angeles in Jan 1862 Generating the scenario details Weather Research & Forecasting (WRF) model’s nested grids Mimi Hughes, NOAA/ESRL,V at the helm From James Done, NCAR ARkStorm Precipitation Totals Daily Precipitation at three locations 6” 20” 20” Percentage of ARkStorm period spent below freezing Ratio of VIC-simulated ARkStorm Runoff vs Historical Periods (1969, 1986) Runoff Maximum Daily Runoff Total Runoff Recurrence Intervals of Maximum 3-day Runoff (relative to WY1916-2003 Historical Simulation) Summary of ARkStorm Meteorological Events Percentage of ARkStorm period spent below freezing.