Preliminary Draft Levy Rate Scenarios for Capital Projects

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Protection Against Wave-Based Erosion

Protection against Wavebased Erosion The guidelines below address the elements of shore structure design common to nearly all erosion control structures subject to direct wave action and run-up. 1. Minimize the extent waterward. Erosion control structures should be designed with the smallest waterward footprint possible. This minimizes the occupation of the lake bottom, limits habitat loss and usually results in a lower cost to construct the project. In the case of stone revetments, the crest width should be only as wide as necessary for a stable structure. In general, the revetment should follow the cross-section of the bluff or dune and be located as close to the bluff or dune as possible. For seawalls, the distance that the structure extends waterward of the upland must be minimized. If the seawall height is appropriately designed to prevent the majority of overtopping, there is no engineering rationale based only on erosion control which justifies extending a seawall out into the water. 2. Minimize the impacts to adjacent properties. The design of the structure must consider the potential for damaging adjacent property. Projects designed to extend waterward of the shore will affect the movement of littoral material, reducing the overall beach forming process which in turn may cause accelerated erosion on adjacent or down-drift properties with less protective beaches. Seawalls, (and to a lesser extent, stone revetments) change the direction (wave reflection) and intensity of wave energy along the shore. Wave reflection can cause an increase in the total energy at the seawall or revetment interface with the water, allowing sand and gravel to remain suspended in the water, which will usually prevent formation of a beach directly fronting the structure. -

Imaging Laurentide Ice Sheet Drainage Into the Deep Sea: Impact on Sediments and Bottom Water

Imaging Laurentide Ice Sheet Drainage into the Deep Sea: Impact on Sediments and Bottom Water Reinhard Hesse*, Ingo Klaucke, Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec H3A 2A7, Canada William B. F. Ryan, Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory of Columbia University, Palisades, NY 10964-8000 Margo B. Edwards, Hawaii Institute of Geophysics and Planetology, University of Hawaii, Honolulu, HI 96822 David J. W. Piper, Geological Survey of Canada—Atlantic, Bedford Institute of Oceanography, Dartmouth, Nova Scotia B2Y 4A2, Canada NAMOC Study Group† ABSTRACT the western Atlantic, some 5000 to 6000 State-of-the-art sidescan-sonar imagery provides a bird’s-eye view of the giant km from their source. submarine drainage system of the Northwest Atlantic Mid-Ocean Channel Drainage of the ice sheet involved (NAMOC) in the Labrador Sea and reveals the far-reaching effects of drainage of the repeated collapse of the ice dome over Pleistocene Laurentide Ice Sheet into the deep sea. Two large-scale depositional Hudson Bay, releasing vast numbers of ice- systems resulting from this drainage, one mud dominated and the other sand bergs from the Hudson Strait ice stream in dominated, are juxtaposed. The mud-dominated system is associated with the short time spans. The repeat interval was meandering NAMOC, whereas the sand-dominated one forms a giant submarine on the order of 104 yr. These dramatic ice- braid plain, which onlaps the eastern NAMOC levee. This dichotomy is the result of rafting events, named Heinrich events grain-size separation on an enormous scale, induced by ice-margin sifting off the (Broecker et al., 1992), occurred through- Hudson Strait outlet. -

Marine Nearshore Restoration Recommendations Whatcom County Shoreline Management Project

Marine Nearshore Restoration Recommendations Whatcom County Shoreline Management Project 1 7 Old Fish 6 Packers Pier Tongue Point Blaine Marina Site Specific Recommendations t pi S o o hm ia m e S Semiahmoo Restoration Site 5 Marina Shoreline Reach Breaks The large platform and foundation could be removed to restore the beach and fringing marsh D Shoreline Modifications 1 2 a kota Cr 3 Removal of bulkheads that protrude into 4 Retaining Walls Remove the intertidal dilapidated Groins and Jetties dock 5 6 Miscellaneous Structures 1 7 C al 8 Piers ifo rn ia 9 2 C r Platforms 4 3 C r 4 nd Bulkheads ra rt Birch Point 5 e Outfall PipesB Cottonwood Beach 6 Building (Shorelines Only) 7 Administrative Boundries r 2 e Birch Bay v Village Marina 3 i 8 R Lummi Nation k Remove groins and bulkheads c a along Birch Bay Drive to restore upper s k beach and backshore habitats Whatcom County oo N e m ns t Mai 2 For more information on restoration sites, includi1ng non site-specific recommendations, see the Whatcom County Shoreline Management Project Inventory & 1 Characterization Report (Backgr1ound document Vol. I) and the Marine Resources Committee Document, Restoration Recommendations by Shoreline Reach by Coastal Ge1o1logic Services and Adolfson and9 Assoc1ia0 tes (2006). 2 DATA SOURCES: Restoration Sites - Coastal Geologic Remove bulkheads along these bluffs, which are the sole Services, Inc., Mod8ifications - WC 2005 (Pictometry 2004), T sediment source for accretionary shoreforms and valuable er r ell C Outfall Pipes - REsources, DNR, Pictometry, Contour lines 2 habitat in Birch Bay and State Park reaches r 1 10 meter intervals, USGS Elevation labels in feet. -

LOUISIANA K. Meyer-Arendt Department of Geography

65. USA--LOUISIANA K. Meyer-Arendt D.W. Davis Department of Geography Department of Earth Science Mississippi State University Nicholls State University Starkville, Mississippi 38759 Thibodaux, Louisiana 70301 United States of America United States of America INTRODUCTION Louisiana's 40,000 Inn 2 coastal zone developed over the last 7,000 years by the progradation, aggradation, and accretion of sediments introduced via various courses of the Mississippi River (Frazier 1967). The deltaic plain (32,000 km'), through which the modern river cuts diagon ally !Fig , 1), consists of vast wetlands and waterbodies. With eleva tions ranging from sea level up to 1.5 m, it is interrupted by natural levee ridges which decrease distally until they disappear beneath the marsh surface. The downdrift chenier plain of southwest Louisiana (8,000 km') consists of marshes, large round-to-oblong lakes, and stranded, oak covered beach ridges known as cheniers (Howe et al. 1935). This landscape is the result of alternating long-term phases of shoreline accretion and erosion that were dependent upon the proximit of an active sediment-laden river, and a low-energy marine environment (Byrne et al. 1959). Since the dyking of the Mississippi River, fluvial sedimentation in the deltaic plain has effectively been halted. Today, most Missis sippi River sediment is deposited on the outer continental shelf; only at the mouth of the Atchafalaya River distributary is deltaic sedimen tation subaerially significant (Adams and Baumann 1980). Over mos of the coastal zone, subsidence, saltwater intrusion, wave erosion, canalization, and other hydrologic modification have led to a rapid increase in the surface area of water (Davis 1986, Walker e al. -

MF2294 Streambank Revetment

Outdated Publication, for historical use. CAUTION: Recommendations in this publication may be obsolete. Kansas State University Agricultural Experiment Station and Cooperative Extension Service Kansas State University, Division of Biology Kansas Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Kansas Department of Wildlife & Parks STREAMBANK REVETMENT 1 Outdated Publication, for historical use. CAUTION: Recommendations in this publication may be obsolete. Introduction Streambank erosion is a naturally occurring process in streams and rivers throughout the United States. Accelerated streambank erosion occurs when natural events or human activities cause a higher than expected amount of erosion, and is typically a result of reduced or eliminated riparian (streamside) vegetation. The removal of riparian vegetation is the primary factor influenc- ing streambank stability. Historically, channel straightening (channelization) was the primary method used to control streambank erosion. However, since the 1970s, riparian and in-stream habitat restoration by natural or artificial meth- ods has grown in popularity because channel- ization typically caused problems, such as ero- sion and flooding dowstream. Natural resource agencies throughout the Midwest have been using tree revetments as one type of streambank stabilization structure. What are tree revetments? Tree revetments are a series of trees laid in the stream along the eroding bank. They are de- signed to reduce water velocity, increase siltation within the trees, and reduce slumping of the streambank. Tree revetments are not designed to permanently stabilize eroding streambanks. They should stabilize the streambank until other stabi- lization techniques, such as tree plantings in the riparian area become established. Tree revet- ments are not designed to fix problems at a watershed level. -

Spatial Variability of Levees As Measured Using the CPT

2nd International Symposium on Cone Penetration Testing, Huntington Beach, CA, USA, May 2010 Spatial Variability of Levees as Measured Using the CPT R.E.S. Moss Assistant Professor, Cal Poly, San Luis Obispo J. C. Hollenback Graduate Researcher, U.C. Berkeley J. Ng Undergraduate Researcher, Cal Poly, San Luis Obispo ABSTRACT: The spatial variability of a soil deposit is something that is commonly discussed but difficult to quantify. The heterogeneity as a function of lateral distance can be critical to the design of long engineered structures such as highways, bridges, levees, and other lifelines. This paper presents a methodology for using CPT mea- surements to quantifying the spatial variability of cone tip resistance along a levee in the California Bay Delta. The results, presented in the form of a general relative va- riogram, identify the distance at which the maximum spatial variability is achieved for a given soil strata. This information helps define minimally correlated stretches of levee for proper failure and risk analysis. Presented herein are methods of interpret- ing, calculating, and analyzing CPT data to arrive at the quantified spatial variability with respect to different static and seismic failure modes common to levee systems. 1 INTRODUCTION Spatial variability of engineering properties in soil strata is inherent to the nature of soil. Spatial variability is controlled primarily by the depositional environment where high energy systems usually deposit materials with high spatial variability (e.g. al- luvial gravels) and low energy systems usually deposit materials with low spatial va- riability (e.g. lacustrine clays). This spatial variability is generally taken into account in geotechnical design in a qualitative empirical manner through appropriately spaced borings to assess the changing subsurface conditions. -

Channel Stabilization Publications Available in Corps of Engineers Offices

TECHNICAL REPORT NO. 4 CHANNEL STABILIZATION PUBLICATIONS AVAILABLE IN CORPS OF ENGINEERS OFFICES i <SESS> ¡01 101 LfU U-U lOi 00¡DE November 1966 Committee on Channel Stabilization CORPS OF ENGINEERS, U. S. ARMY REPORTS OF COMMITTEE ON CHANNEL STABILIZATION ¿i BUREAU OF RECLAMATION DENVER Lll 92035635 VT ■ieD3Sb3S nsJjfe-» TECHNICAL REPORT 4 7 3 CHANNEL STABILIZATION PUBLICATIONS AVAILABLE IN CORPS OF ENGINEERS OFFICES j f November 1966 f Committee on Channel Stabilization - i / y > CORPS OF ENGINEERS/ U. S. ARMY ARM Y-MRC VICKSBURG. MISS. PRESENT MEMBERSHIP OF COMMITTEE ON CHANNEL STABILIZATION J. H. Douma Office, Chief of Engineers Chairman E. B. Lipscomb Lower Mississippi Valley Division Recorder D. C. Bondurant Missouri River Division R. H. Haas Lower Mississippi Valley Division W. E. Isaacs Little Rock District C. P. Lindner South Atlantic Division E. B. Madden Southwestern Division H. A. Smith North Pacific Division J. B. Tiffany Waterways Experiment Station G. B. Fenwick Consultant FOREWORD Establishment of the Committee on Channel Stabilization in April 1962 was confirmed by Engineer Regulation 15-2-1, dated 1 November 1962. As stated in ER 15-2-1, the objectives of the Committee with respect to channel stabilization are: a. To review and evaluate pertinent information and disseminate the results thereof. b. To determine the need for and recommend a program of research; and to have advisory technical review responsibility for research assigned to the Committee. £. To determine basic principles and design criteria. d. To provide, at the request of field offices, advice on design and operational problems. In accordance with the desire of the Committee to inventory available data, reports, papers, etc., pertaining to channel stabilization, arrangements were made for the Research Center Library, U. -

Tree Revetments

Tree Revetments Tree revetments are cut increase bank erosion. It trees anchored at the bottom is extremely important (or toe) of unstable stream- to anchor each tree in the banks. These anchored trees revetment at the base or toe serve to slow the current of the eroding bank. This is along the bank, decreasing the point of the bank where erosion and allowing the vertical bank meets the sediment to be deposited horizontal bottom (Figure 2). within the tree branches. If the trees are anchored too Trees with many fine limbs high on the bank, the water and branches are best at may undercut the structure. slowing near-bank currents, If they are placed out in the catching sediment carried channel too far, the current in the stream, and catching Figure 1. Cedar revetment and willow stakes after 3 months. will continue to erode the slump material from the bank. bank behind the revetment. example of this would be stream For this reason, eastern redcedar Another consideration is the soil straightening (or channelization). is usually the best choice. Eastern type and texture that the anchors One indication of this situation redcedar is also more resistant to will be driven into. Sandy or rocky is when a streambank is covered decay than hardwood trees. soils will usually require a larger with trees and vegetation and is The sediment trapped in and anchor driven to a greater depth still eroding. If that is the case, behind revetments provides a while smaller anchors may be a tree revetment may not work. moist, fertile seedbed for vegetation used in heavier clay soils. -

Part 629 – Glossary of Landform and Geologic Terms

Title 430 – National Soil Survey Handbook Part 629 – Glossary of Landform and Geologic Terms Subpart A – General Information 629.0 Definition and Purpose This glossary provides the NCSS soil survey program, soil scientists, and natural resource specialists with landform, geologic, and related terms and their definitions to— (1) Improve soil landscape description with a standard, single source landform and geologic glossary. (2) Enhance geomorphic content and clarity of soil map unit descriptions by use of accurate, defined terms. (3) Establish consistent geomorphic term usage in soil science and the National Cooperative Soil Survey (NCSS). (4) Provide standard geomorphic definitions for databases and soil survey technical publications. (5) Train soil scientists and related professionals in soils as landscape and geomorphic entities. 629.1 Responsibilities This glossary serves as the official NCSS reference for landform, geologic, and related terms. The staff of the National Soil Survey Center, located in Lincoln, NE, is responsible for maintaining and updating this glossary. Soil Science Division staff and NCSS participants are encouraged to propose additions and changes to the glossary for use in pedon descriptions, soil map unit descriptions, and soil survey publications. The Glossary of Geology (GG, 2005) serves as a major source for many glossary terms. The American Geologic Institute (AGI) granted the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service (formerly the Soil Conservation Service) permission (in letters dated September 11, 1985, and September 22, 1993) to use existing definitions. Sources of, and modifications to, original definitions are explained immediately below. 629.2 Definitions A. Reference Codes Sources from which definitions were taken, whole or in part, are identified by a code (e.g., GG) following each definition. -

APPENDIX L L.1 Principal Mechanism of Sea Dike and Revetment Failure In

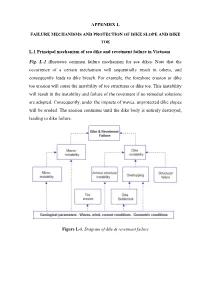

APPENDIX L FAILURE MECHANISMS AND PROTECTION OF DIKE SLOPE AND DIKE TOE L.1 Principal mechanism of sea dike and revetment failure in Vietnam Fig. L-1 illustrates common failure mechanism for sea dikes. Note that the occurrence of a certain mechanism will sequentially result in others, and consequently leads to dike breach. For example, the foreshore erosion or dike toe erosion will cause the instability of toe structures or dike toe. This instability will result in the instability and failure of the revetment if no remedial solutions are adopted. Consequently, under the impacts of waves, unprotected dike slopes will be eroded. The erosion continues until the dike body is entirely destroyed, leading to dike failure. Figure L-1. Diagram of dike & revetment failure 4 2 3 DWL 0 i 1 h original cross-shore profile h at design situation scour holes 1- instability of toe structures 2- instability of slope protection 3- erosion of outer slope 4- erosion of dike crest and inner slope Foreshore erosion (3) Instability of toe protection structures (1) Overflow due to foreshore erosion and local erosion of dike toe (1a) Overtopping; resulting in erosion (4) Inner slope sliding of crest and inner slope (1b) Overtopping; resulting in inner (5) Outer slope sliding slope sliding (6) Internal erosion; piping (2) Instability of outer amour structures/dike slope and body erosion Figure L-2. Typical failure of sea dike In the following sections, details of common failure mechanism of sea dike and revetment system in Vietnam will be given. L.1.1 Wave overtopping Wave overtopping is the dominant mechanism of sea dike failure in Vietnam, as most of sea dikes are overtopped during storms and flood, even in the long-lasting monsoon period. -

Design of Riprap Revetment HEC 11 Metric Version

Design of Riprap Revetment HEC 11 Metric Version Welcome to HEC 11-Design of Riprap Revetment. Table of Contents Preface Tech Doc U.S. - SI Conversions DISCLAIMER: During the editing of this manual for conversion to an electronic format, the intent has been to convert the publication to the metric system while keeping the document as close to the original as possible. The document has undergone editorial update during the conversion process. Archived Table of Contents for HEC 11-Design of Riprap Revetment (Metric) List of Figures List of Tables List of Charts & Forms List of Equations Cover Page : HEC 11-Design of Riprap Revetment (Metric) Chapter 1 : HEC 11 Introduction 1.1 Scope 1.2 Recognition of Erosion Potential 1.3 Erosion Mechanisms and Riprap Failure Modes Chapter 2 : HEC 11 Revetment Types 2.1 Riprap 2.1.1 Rock Riprap 2.1.2 Rubble Riprap 2.2 Wire-Enclosed Rock 2.3 Pre-Cast Concrete Block 2.4 Grouted Rock 2.5 Paved Lining Chapter 3 : HEC 11 Design Concepts 3.1 Design Discharge 3.2 Flow Types 3.3 Section Geometry 3.4 Flow in Channel Bends 3.5 Flow Resistance 3.6 Extent of Protection 3.6.1 Longitudinal Extent 3.6.2 Vertical Extent 3.6.2.1 Design Height 3.6.2.2 Toe Depth Chapter 4 : HEC 11 Design Guidelines for Rock Riprap 4.1 Rock Size Archived 4.1.1 Particle Erosion 4.1.1.1 Design Relationship 4.1.1.2 Application 4.1.2 Wave Erosion 4.1.3 Ice Damage 4.2 Rock Gradation 4.3 Layer Thickness 4.4 Filter Design 4.4.1 Granular Filters 4.4.2 Fabric Filters 4.5 Material Quality 4.6 Edge Treatment 4.7 Construction Chapter 5 : HEC 11 Rock -

Documentation of Design Deficiencies Santa Clara River Levee System (Scr-1) 1

DOCUMENTATION OF DESIGN DEFICIENCIES SANTA CLARA RIVER LEVEE SYSTEM (SCR-1) 1. Project Description and Watershed Characteristics The Santa Clara River Levee (SCR-1) system is located in the city of Oxnard, in Ventura County, California. It is approximately 4.72 miles long, extending along the southeast bank of the Santa Clara River from Highway 101, at its downstream terminus, to the community of Saticoy, at its upstream terminus (see Figure 1). SCR-1 was originally designed in 1958 by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (Corps) to control the Corps’ predicted Standard Project Flood peak discharge of 225,000 cubic feet per second (cfs), a peak emanating from a partially regulated 1,600-square-mile Santa Clara River watershed. The height of SCR-1 varies from approximately 4 feet to 13 feet. The compacted fill embankment that forms SCR-1 has a top width of 18 feet. The levee embankment slopes are 2 horizontal to 1 vertical (2H:1V), on both the landward side and the riverward side. The riverward side of the embankment has a 1.5- to 2- foot-thick rock revetment, with a concrete facing at and near highway bridges. The rock revetment extends from the top of the embankment to varying depths. The lowest depth of the rock revetment is hereinafter referred to as the “toedown.” Construction of the SCR-1 project was completed in 1961. The levee was constructed adjacent to the active channel of the Santa Clara River. A review of historical aerial photography, dating as far back as 1927, indicates that before construction of the SCR-1, there were numerous locations along the project reach where the primary braid of the Santa Clara River impinged directly on the east and west banks of the river at rather abrupt flow angles.