A Stream Evolution Model Integrating Habitat and Ecosystem Benefits

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Protection Against Wave-Based Erosion

Protection against Wavebased Erosion The guidelines below address the elements of shore structure design common to nearly all erosion control structures subject to direct wave action and run-up. 1. Minimize the extent waterward. Erosion control structures should be designed with the smallest waterward footprint possible. This minimizes the occupation of the lake bottom, limits habitat loss and usually results in a lower cost to construct the project. In the case of stone revetments, the crest width should be only as wide as necessary for a stable structure. In general, the revetment should follow the cross-section of the bluff or dune and be located as close to the bluff or dune as possible. For seawalls, the distance that the structure extends waterward of the upland must be minimized. If the seawall height is appropriately designed to prevent the majority of overtopping, there is no engineering rationale based only on erosion control which justifies extending a seawall out into the water. 2. Minimize the impacts to adjacent properties. The design of the structure must consider the potential for damaging adjacent property. Projects designed to extend waterward of the shore will affect the movement of littoral material, reducing the overall beach forming process which in turn may cause accelerated erosion on adjacent or down-drift properties with less protective beaches. Seawalls, (and to a lesser extent, stone revetments) change the direction (wave reflection) and intensity of wave energy along the shore. Wave reflection can cause an increase in the total energy at the seawall or revetment interface with the water, allowing sand and gravel to remain suspended in the water, which will usually prevent formation of a beach directly fronting the structure. -

Marine Nearshore Restoration Recommendations Whatcom County Shoreline Management Project

Marine Nearshore Restoration Recommendations Whatcom County Shoreline Management Project 1 7 Old Fish 6 Packers Pier Tongue Point Blaine Marina Site Specific Recommendations t pi S o o hm ia m e S Semiahmoo Restoration Site 5 Marina Shoreline Reach Breaks The large platform and foundation could be removed to restore the beach and fringing marsh D Shoreline Modifications 1 2 a kota Cr 3 Removal of bulkheads that protrude into 4 Retaining Walls Remove the intertidal dilapidated Groins and Jetties dock 5 6 Miscellaneous Structures 1 7 C al 8 Piers ifo rn ia 9 2 C r Platforms 4 3 C r 4 nd Bulkheads ra rt Birch Point 5 e Outfall PipesB Cottonwood Beach 6 Building (Shorelines Only) 7 Administrative Boundries r 2 e Birch Bay v Village Marina 3 i 8 R Lummi Nation k Remove groins and bulkheads c a along Birch Bay Drive to restore upper s k beach and backshore habitats Whatcom County oo N e m ns t Mai 2 For more information on restoration sites, includi1ng non site-specific recommendations, see the Whatcom County Shoreline Management Project Inventory & 1 Characterization Report (Backgr1ound document Vol. I) and the Marine Resources Committee Document, Restoration Recommendations by Shoreline Reach by Coastal Ge1o1logic Services and Adolfson and9 Assoc1ia0 tes (2006). 2 DATA SOURCES: Restoration Sites - Coastal Geologic Remove bulkheads along these bluffs, which are the sole Services, Inc., Mod8ifications - WC 2005 (Pictometry 2004), T sediment source for accretionary shoreforms and valuable er r ell C Outfall Pipes - REsources, DNR, Pictometry, Contour lines 2 habitat in Birch Bay and State Park reaches r 1 10 meter intervals, USGS Elevation labels in feet. -

LOUISIANA K. Meyer-Arendt Department of Geography

65. USA--LOUISIANA K. Meyer-Arendt D.W. Davis Department of Geography Department of Earth Science Mississippi State University Nicholls State University Starkville, Mississippi 38759 Thibodaux, Louisiana 70301 United States of America United States of America INTRODUCTION Louisiana's 40,000 Inn 2 coastal zone developed over the last 7,000 years by the progradation, aggradation, and accretion of sediments introduced via various courses of the Mississippi River (Frazier 1967). The deltaic plain (32,000 km'), through which the modern river cuts diagon ally !Fig , 1), consists of vast wetlands and waterbodies. With eleva tions ranging from sea level up to 1.5 m, it is interrupted by natural levee ridges which decrease distally until they disappear beneath the marsh surface. The downdrift chenier plain of southwest Louisiana (8,000 km') consists of marshes, large round-to-oblong lakes, and stranded, oak covered beach ridges known as cheniers (Howe et al. 1935). This landscape is the result of alternating long-term phases of shoreline accretion and erosion that were dependent upon the proximit of an active sediment-laden river, and a low-energy marine environment (Byrne et al. 1959). Since the dyking of the Mississippi River, fluvial sedimentation in the deltaic plain has effectively been halted. Today, most Missis sippi River sediment is deposited on the outer continental shelf; only at the mouth of the Atchafalaya River distributary is deltaic sedimen tation subaerially significant (Adams and Baumann 1980). Over mos of the coastal zone, subsidence, saltwater intrusion, wave erosion, canalization, and other hydrologic modification have led to a rapid increase in the surface area of water (Davis 1986, Walker e al. -

MF2294 Streambank Revetment

Outdated Publication, for historical use. CAUTION: Recommendations in this publication may be obsolete. Kansas State University Agricultural Experiment Station and Cooperative Extension Service Kansas State University, Division of Biology Kansas Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Kansas Department of Wildlife & Parks STREAMBANK REVETMENT 1 Outdated Publication, for historical use. CAUTION: Recommendations in this publication may be obsolete. Introduction Streambank erosion is a naturally occurring process in streams and rivers throughout the United States. Accelerated streambank erosion occurs when natural events or human activities cause a higher than expected amount of erosion, and is typically a result of reduced or eliminated riparian (streamside) vegetation. The removal of riparian vegetation is the primary factor influenc- ing streambank stability. Historically, channel straightening (channelization) was the primary method used to control streambank erosion. However, since the 1970s, riparian and in-stream habitat restoration by natural or artificial meth- ods has grown in popularity because channel- ization typically caused problems, such as ero- sion and flooding dowstream. Natural resource agencies throughout the Midwest have been using tree revetments as one type of streambank stabilization structure. What are tree revetments? Tree revetments are a series of trees laid in the stream along the eroding bank. They are de- signed to reduce water velocity, increase siltation within the trees, and reduce slumping of the streambank. Tree revetments are not designed to permanently stabilize eroding streambanks. They should stabilize the streambank until other stabi- lization techniques, such as tree plantings in the riparian area become established. Tree revet- ments are not designed to fix problems at a watershed level. -

Channel Stabilization Publications Available in Corps of Engineers Offices

TECHNICAL REPORT NO. 4 CHANNEL STABILIZATION PUBLICATIONS AVAILABLE IN CORPS OF ENGINEERS OFFICES i <SESS> ¡01 101 LfU U-U lOi 00¡DE November 1966 Committee on Channel Stabilization CORPS OF ENGINEERS, U. S. ARMY REPORTS OF COMMITTEE ON CHANNEL STABILIZATION ¿i BUREAU OF RECLAMATION DENVER Lll 92035635 VT ■ieD3Sb3S nsJjfe-» TECHNICAL REPORT 4 7 3 CHANNEL STABILIZATION PUBLICATIONS AVAILABLE IN CORPS OF ENGINEERS OFFICES j f November 1966 f Committee on Channel Stabilization - i / y > CORPS OF ENGINEERS/ U. S. ARMY ARM Y-MRC VICKSBURG. MISS. PRESENT MEMBERSHIP OF COMMITTEE ON CHANNEL STABILIZATION J. H. Douma Office, Chief of Engineers Chairman E. B. Lipscomb Lower Mississippi Valley Division Recorder D. C. Bondurant Missouri River Division R. H. Haas Lower Mississippi Valley Division W. E. Isaacs Little Rock District C. P. Lindner South Atlantic Division E. B. Madden Southwestern Division H. A. Smith North Pacific Division J. B. Tiffany Waterways Experiment Station G. B. Fenwick Consultant FOREWORD Establishment of the Committee on Channel Stabilization in April 1962 was confirmed by Engineer Regulation 15-2-1, dated 1 November 1962. As stated in ER 15-2-1, the objectives of the Committee with respect to channel stabilization are: a. To review and evaluate pertinent information and disseminate the results thereof. b. To determine the need for and recommend a program of research; and to have advisory technical review responsibility for research assigned to the Committee. £. To determine basic principles and design criteria. d. To provide, at the request of field offices, advice on design and operational problems. In accordance with the desire of the Committee to inventory available data, reports, papers, etc., pertaining to channel stabilization, arrangements were made for the Research Center Library, U. -

Tree Revetments

Tree Revetments Tree revetments are cut increase bank erosion. It trees anchored at the bottom is extremely important (or toe) of unstable stream- to anchor each tree in the banks. These anchored trees revetment at the base or toe serve to slow the current of the eroding bank. This is along the bank, decreasing the point of the bank where erosion and allowing the vertical bank meets the sediment to be deposited horizontal bottom (Figure 2). within the tree branches. If the trees are anchored too Trees with many fine limbs high on the bank, the water and branches are best at may undercut the structure. slowing near-bank currents, If they are placed out in the catching sediment carried channel too far, the current in the stream, and catching Figure 1. Cedar revetment and willow stakes after 3 months. will continue to erode the slump material from the bank. bank behind the revetment. example of this would be stream For this reason, eastern redcedar Another consideration is the soil straightening (or channelization). is usually the best choice. Eastern type and texture that the anchors One indication of this situation redcedar is also more resistant to will be driven into. Sandy or rocky is when a streambank is covered decay than hardwood trees. soils will usually require a larger with trees and vegetation and is The sediment trapped in and anchor driven to a greater depth still eroding. If that is the case, behind revetments provides a while smaller anchors may be a tree revetment may not work. moist, fertile seedbed for vegetation used in heavier clay soils. -

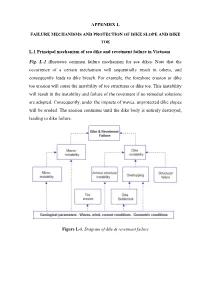

APPENDIX L L.1 Principal Mechanism of Sea Dike and Revetment Failure In

APPENDIX L FAILURE MECHANISMS AND PROTECTION OF DIKE SLOPE AND DIKE TOE L.1 Principal mechanism of sea dike and revetment failure in Vietnam Fig. L-1 illustrates common failure mechanism for sea dikes. Note that the occurrence of a certain mechanism will sequentially result in others, and consequently leads to dike breach. For example, the foreshore erosion or dike toe erosion will cause the instability of toe structures or dike toe. This instability will result in the instability and failure of the revetment if no remedial solutions are adopted. Consequently, under the impacts of waves, unprotected dike slopes will be eroded. The erosion continues until the dike body is entirely destroyed, leading to dike failure. Figure L-1. Diagram of dike & revetment failure 4 2 3 DWL 0 i 1 h original cross-shore profile h at design situation scour holes 1- instability of toe structures 2- instability of slope protection 3- erosion of outer slope 4- erosion of dike crest and inner slope Foreshore erosion (3) Instability of toe protection structures (1) Overflow due to foreshore erosion and local erosion of dike toe (1a) Overtopping; resulting in erosion (4) Inner slope sliding of crest and inner slope (1b) Overtopping; resulting in inner (5) Outer slope sliding slope sliding (6) Internal erosion; piping (2) Instability of outer amour structures/dike slope and body erosion Figure L-2. Typical failure of sea dike In the following sections, details of common failure mechanism of sea dike and revetment system in Vietnam will be given. L.1.1 Wave overtopping Wave overtopping is the dominant mechanism of sea dike failure in Vietnam, as most of sea dikes are overtopped during storms and flood, even in the long-lasting monsoon period. -

Design of Riprap Revetment HEC 11 Metric Version

Design of Riprap Revetment HEC 11 Metric Version Welcome to HEC 11-Design of Riprap Revetment. Table of Contents Preface Tech Doc U.S. - SI Conversions DISCLAIMER: During the editing of this manual for conversion to an electronic format, the intent has been to convert the publication to the metric system while keeping the document as close to the original as possible. The document has undergone editorial update during the conversion process. Archived Table of Contents for HEC 11-Design of Riprap Revetment (Metric) List of Figures List of Tables List of Charts & Forms List of Equations Cover Page : HEC 11-Design of Riprap Revetment (Metric) Chapter 1 : HEC 11 Introduction 1.1 Scope 1.2 Recognition of Erosion Potential 1.3 Erosion Mechanisms and Riprap Failure Modes Chapter 2 : HEC 11 Revetment Types 2.1 Riprap 2.1.1 Rock Riprap 2.1.2 Rubble Riprap 2.2 Wire-Enclosed Rock 2.3 Pre-Cast Concrete Block 2.4 Grouted Rock 2.5 Paved Lining Chapter 3 : HEC 11 Design Concepts 3.1 Design Discharge 3.2 Flow Types 3.3 Section Geometry 3.4 Flow in Channel Bends 3.5 Flow Resistance 3.6 Extent of Protection 3.6.1 Longitudinal Extent 3.6.2 Vertical Extent 3.6.2.1 Design Height 3.6.2.2 Toe Depth Chapter 4 : HEC 11 Design Guidelines for Rock Riprap 4.1 Rock Size Archived 4.1.1 Particle Erosion 4.1.1.1 Design Relationship 4.1.1.2 Application 4.1.2 Wave Erosion 4.1.3 Ice Damage 4.2 Rock Gradation 4.3 Layer Thickness 4.4 Filter Design 4.4.1 Granular Filters 4.4.2 Fabric Filters 4.5 Material Quality 4.6 Edge Treatment 4.7 Construction Chapter 5 : HEC 11 Rock -

Crescent Beach Seawall and Revetment Repair Hull, Massachusetts June 30, 2015

Environmental Notification Form Crescent Beach Seawall and Revetment Repair Hull, Massachusetts June 30, 2015 Prepared by: Applied Coastal Research and Engineering, Inc. 766 Falmouth Road, Suite A1 Mashpee, Massachusetts 02649 Prepared for: Town of Hull Conservation Department 253 Atlantic Avenue Hull, Massachusetts 02045 Environmental Notification Form Crescent Beach, Hull, MA TABLE OF CONTENTS ENF Distribution List .................................................................................................... iv Environmental Notification Form ................................................................................. v USGS Map ..................................................................................................................... vi 1.0 Project Overview ................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Introduction ....................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Description of Project Area ................................................................................ 1 1.2 Project Area History .......................................................................................... 2 1.3 MEPA Review Thresholds ................................................................................. 5 2.0 Existing Conditions ............................................................................................ 6 2.1 Existing Seawall and Revetment ...................................................................... -

Preliminary Draft Levy Rate Scenarios for Capital Projects

King County Regional Flood Control Zone District Advisory Committee Preliminary Draft: Levy Rate Scenarios for Capital Projects Notes: 1. Questions for Advisory Committee meeting on 6/22: (a) Do you want to include projects that address coastal erosion and inundation hazards? (b) Do you support including new project submittals as part of this list? (c) What levy rate do you support? (d) Do you want to fund subregional projects? If so, at what level? 2. Project costs are planning estimates only. Constant dollar (2006) costs are used to control for the effect of inflation on project sequencing. Operating costs for programmatic elements of work program are not included. 3. All new capital projects submitted to the BTCs as 'Regional' are included in this list and shaded. New capital projects total $55 million. New project submittals range in cost from $100,000 (Carnation - Tolt Supplemental Study) to $21,900,000 (Bellevue- Coal Creek Phase 1 and 2). 4. Projects submitted as 'subregional' are included at the end of this list. No call for proposals was issued for this category, and no scoring has been conducted by the BTCs. We have received $57.8 million in proposals to date, and expect that this amount would increase substantially if an RFP were issued. 5. Changes from the 6/8/07 List: (a) The two Bellevue projects submitted as 'Regional' are included. Coal Creek project sequenced in two phases of $12.5 million and $9.4 million based on discussions with Bellevue staff (b) Dorre Don Meanders phased to reduce costs to $7.5 million in the 10-yr window, remaining acquisition costs of $7 million assumed in Phase 2. -

Design of Riprap Revetment

, 1-) r-) P .A) C? F Hydraulic Engineering Circular No. 11 U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Highway Publication Na FHWA-lP-89-016 Administration March 1989 Design of Riprap Revetment Research, Development, and-T"echnology Turner-Fairbank Highwayffesewch Center 6300 Gec rg3#own Pike McLean, V'wffiniae=-2296 WATER RESOURCES ' RESEARCH LABORATORY J OFFICIAL FILE COPY Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient's Catalog No. FHWA-IP-89-016 HEC-11 4, Title and Subtitle S. Report Dote March 1989 DESIGN OF RIPRAP REVETMENT 6. Performing Organization Code 8. Performing Organization Report No. 7, Aurhorrs) Scott A. Brown, Eric S. Clyde 9, Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS) Sutron Corporation 3D9C0033 2190 Fox Mill Road 11. Contract or Grant No. Herndon, VA 22071 DTFH61-85-C-00123 13. Type of Report and Period Covered 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address Office of Implementation, HRT-10 Final Report Federal Highway Administration Mar. 1986 - Sept. 1988 6200 Georgetown Pike McLean, VA 22101 14. Sponsoring Agency Code 15. Supplementary Notes Project Manager: Thomas Krylowski Technical Assistants: Philip L. Thompson, Dennis L. Richards, J. Sterling Jones 16. Abstract This revised version of Hydraulic Engineering Circular No. 11 (HEC-11), represents major revisions to the earlier (1967) edition of HEC-11. Recent research findings and revised design procedures have been incorporated. The manual has been expanded into a comprehensive design publication. The revised manual includes discussions on recognizing erosion potential, erosion mechanisms and riprap failure modes, riprap types including rock riprap, rubble riprap, gabions, preformed blocks, grouted rock, and paved linings. -

Appendix G. Flood Hazard Management Risk Areas

APPENDIX G. FLOOD HAZARD MANAGEMENT RISK AREAS This appendix contains a complete listing of the flooding and erosion related risk areas identified by the River and Floodplain Management Program staff during the preparation of the 2006 King County Flood Hazard Management Plan. The approach to identifying and characterizing these risk areas varied from river to river and was influenced by both the characteristics of each river, and by the professional judgment of the team compiling this information. This risk identification was the first step in the development of project and program proposals contained in Appendices E and F of this Plan. These project and program recommendation are cross referenced in the last columns of this table. In many cases the magnitude of these risks described is not well understood but will be further evaluated through future technical studies and risk assessments. South Fork Skykomish River, Miller River, Maloney Creek, Tye River and Anthracite Creek (WRIA 7) In DS US Bank Flood or Channel Migration Risk Action Proposed Project RM RM Plan? 6.4 19.9 L, R South Fork Skykomish River Channel Migration Zone Y South Fork Skykomish Channel Migration Zone: Study and Map: Channel migration is a type of flood Conduct South Fork Skykomish River Channel Migration hazard. King County maps channel migration zones to Zone Study and Mapping. (Skykomish River, identify the extent of this flood hazard and regulate land use Unincorporated) in the affected areas. Historical and recent evidence indicates that this part of the South Fork Skykomish River is subject to channel migration. A South Fork Skykomish River channel migration zone study and map will be completed under this project for use by the King County Department of Development and Environmental Services in land use regulation within King County.