Florida Historical Quarterly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Fourteenth Colony: Florida and the American Revolution in the South

THE FOURTEENTH COLONY: FLORIDA AND THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION IN THE SOUTH By ROGER C. SMITH A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2011 1 © 2011 Roger C. Smith 2 To my mother, who generated my fascination for all things historical 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank Jon Sensbach and Jessica Harland-Jacobs for their patience and edification throughout the entire writing process. I would also like to thank Ida Altman, Jack Davis, and Richmond Brown for holding my feet to the path and making me a better historian. I owe a special debt to Jim Cusack, John Nemmers, and the rest of the staff at the P.K. Yonge Library of Florida History and Special Collections at the University of Florida for introducing me to this topic and allowing me the freedom to haunt their facilities and guide me through so many stages of my research. I would be sorely remiss if I did not thank Steve Noll for his efforts in promoting the University of Florida’s history honors program, Phi Alpha Theta; without which I may never have met Jim Cusick. Most recently I have been humbled by the outpouring of appreciation and friendship from the wonderful people of St. Augustine, Florida, particularly the National Association of Colonial Dames, the ladies of the Women’s Exchange, and my colleagues at the St. Augustine Lighthouse and Museum and the First America Foundation, who have all become cherished advocates of this project. -

South Carolina Loyalists in the American Revolution South Carolina in 1776 (Adapted by R

South Carolina Loyalists in the American Revolution South Carolina in 1776 (adapted by R. S. Lambert from James Cook, 1773) Note: Broken lines, combined with natural features (e.g. rivers) delineate boundaries of judicial districts. Robert Stansbury Lambert Second Edition Works produced at Clemson University by the Center for Electronic and Digital Publishing, including Th e South Carolina Review and its themed series “Virginia Woolf International,” “Ireland in the Arts and Humanities,” and “James Dickey Revisited” may be found at our Web site: http://www.clemson.edu/caah/cedp. Contact the director at 864-656-5399 for information. Copyright 2010 by Clemson University ISBN 978-0-9842598-8-5 Second Edition CLEMSON UNIVERSITY DIGITAL PRESS Published by Clemson University Digital Press at the Center for Electronic and Digital Publishing, Clemson University, Clemson, South Carolina. Editorial Assistants: Christina Cook, Ashley Dannelly, Steve Johnson, Carrie Kolb Cover Design: Christina Cook Produced with the Adobe Creative Suite CS5 and Microsoft Word. Th is book is set in Adobe Garamond Pro and was printed by University Printing Services, Offi ce of Publica- tions and Promotional Services, Clemson University. To order copies, contact the Center for Electronic and Digital Publishing, Strode Tower, Box 340522, Clemson University, Clemson, South Carolina 29634-0522. To Edythe and Anne Contents Preface .......................................................................................................... viii Abbreviations and Acronyms ....................................................................... -

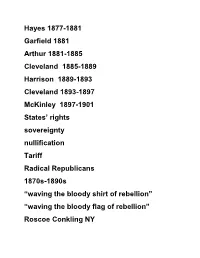

List for 202 First Exam

Hayes 1877-1881 Garfield 1881 Arthur 1881-1885 Cleveland 1885-1889 Harrison 1889-1893 Cleveland 1893-1897 McKinley 1897-1901 States’ rights sovereignty nullification Tariff Radical Republicans 1870s-1890s “waving the bloody shirt of rebellion” “waving the bloody flag of rebellion” Roscoe Conkling NY James G. Blaine Maine “Millionnaires’ Club” “the Railroad Lobby” 1. Conservative Rep party in control 2. Economy fluctuates a. Poor economy, prosperity, depression b. 1873 1893 1907 1929 c. Significant technological advances 3. Significant social changes 1876 Disputed Election of 1876 Rep- Rutherford B. Hayes Ohio Dem-Samuel Tilden NY To win 185 Tilden 184 + 1 Hayes 165 + 20 Fl SC La Oreg January 1877 Electoral Commission of 15 5 H, 5S, 5SC 7 R, 7 D, 1LR 8 to 7 Compromise of 1877 1. End reconstruction April 30, 1877 2. Appt s. Dem. Cab David Key PG 3. Support funds for internal improvements in the South Hayes 1877-1881 “ole 8 and 7 Hayes” “His Fraudulency” Carl Schurz Wm Everts Civil Service Reform Chester A. Arthur Great Strike of 1877 Resumption Act 1875 specie Bland Allison Silver Purchase Act 1878 16:1 $2-4 million/mo Silver certificates 1880 James G. Blaine Blaine Halfbreeds Rep James A Garfield Ohio Chester A. Arthur Roscoe Conkling Conkling Stalwarts Grant Dem Winfield Scott Hancock PA Greenback Party James B. Weaver Iowa Battle of the 3 Generals 1881 Arthur Pendleton Civil Service Act 1883 Chicago and Boston 1884 Election Rep. Blaine of Maine Mugwumps Dem. Grover Cleveland NY “Rum, Romanism and Rebellion” 1885-1889 Character Union Veterans Grand Army of the Republic GAR LQC Lamar S of Interior 1862 union pension 1887 Dependent Pension Bill Interstate Commerce Act 1887 ICC Pooling, rebates, drawbacks Prohibit discrimination John D. -

Digital USFSP

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Special Collections and University Archives Finding Aids and Research Guides for Finding Aids: All Items Manuscript and Special Collections 4-1-2006 Papers of Hazel A. Talley Evans : A Collection Guide Nelson Poynter Memorial Library. Special Collections and University Archives. James Anthony Schnur Laura Woodruff Susan Hickok 1947-2008 Hazel Talley Evans 1931-1997. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scua_finding_aid_all Part of the Archival Science Commons Scholar Commons Citation Nelson Poynter Memorial Library. Special Collections and University Archives.; Schnur, James Anthony; Woodruff, Laura; Hickok, Susan 1947-2008; and Evans, Hazel Talley 1931-1997., "Papers of Hazel A. Talley Evans : A Collection Guide" (2006). Special Collections and University Archives Finding Aids: All Items. 34. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scua_finding_aid_all/34 This Other is brought to you for free and open access by the Finding Aids and Research Guides for Manuscript and Special Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Special Collections and University Archives Finding Aids: All Items by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Papers of Hazel A. Talley Evans A Collection Guide by J im S chnur Assistant Librarian Laura W oodruff and S usan H ickok Archives Interns S pecial Collections and Archives N elson Poynter M em orial Library U niversity of S outh Florida S t. Petersburg April 2006 Introduction to the Collection The Nelson Poynter Memorial Library acquired the papers of Hazel A. Talley Evans (16 August 1931-10 December 1997) in December 2001 from Robert Winfield “Bob” Evans (1924-2005), her second husband. -

Uniting Mugwumps and the Masses: the Role of Puck in Gilded Age Politics, 1880-1884

Uniting Mugwumps and the Masses: The Role of Puck in Gilded Age Politics, 1880-1884 Daniel Henry Backer McLean, Virginia B.A., University of Notre Dame, 1994 A Thesis presented to 1he Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of English University of Virginia August 1996 WARNING! The document you now hold in your hands is a feeble reproduction of an experiment in hypertext. In the waning years of the twentieth century, a crude network of computerized information centers formed a system called the Internet; one particular format of data retrieval combined text and digital images and was known as the World Wide Web. This particular project was designed for viewing through Netscape 2.0. It can be found at http://xroads.virginia.edu/~MA96/PUCK/ If you are able to locate this Website, you will soon realize it is a superior resource for the presentation of such a highly visual magazine as Puck. 11 Table of Contents Introduction 1 I) A Brief History of Cartoons 5 II) Popular and Elite Political Culture 13 III) A Popular Medium 22 "Our National Dog Show" 32 "Inspecting the Democratic Curiosity Shop" 35 Caricature and the Carte-de-Viste 40 The Campaign Against Grant 42 EndNotes 51 Bibliography 54 1 wWhy can the United States not have a comic paper of its own?" enquired E.L. Godkin of The Nation, one of the most distinguished intellectual magazines of the Gilded Age. America claimed a host of popular and insightful raconteurs as its own, from Petroleum V. -

Gold Democrats and the Decline of Classical Liberalism, 1896–1900

SUBSCRIBE NOW AND RECEIVE CRISIS AND LEVIATHAN* FREE! “The Independent Review does not accept “The Independent Review is pronouncements of government officials nor the excellent.” conventional wisdom at face value.” —GARY BECKER, Noble Laureate —JOHN R. MACARTHUR, Publisher, Harper’s in Economic Sciences Subscribe to The Independent Review and receive a free book of your choice* such as the 25th Anniversary Edition of Crisis and Leviathan: Critical Episodes in the Growth of American Government, by Founding Editor Robert Higgs. This quarterly journal, guided by co-editors Christopher J. Coyne, and Michael C. Munger, and Robert M. Whaples offers leading-edge insights on today’s most critical issues in economics, healthcare, education, law, history, political science, philosophy, and sociology. Thought-provoking and educational, The Independent Review is blazing the way toward informed debate! Student? Educator? Journalist? Business or civic leader? Engaged citizen? This journal is for YOU! *Order today for more FREE book options Perfect for students or anyone on the go! The Independent Review is available on mobile devices or tablets: iOS devices, Amazon Kindle Fire, or Android through Magzter. INDEPENDENT INSTITUTE, 100 SWAN WAY, OAKLAND, CA 94621 • 800-927-8733 • [email protected] PROMO CODE IRA1703 Gold Democrats and the Decline of Classical Liberalism, 1896–1900 —————— ✦ —————— DAVID T. BEITO AND LINDA ROYSTER BEITO n 1896 a new political party was born, the National Democratic Party (NDP). The founders of the NDP included some of the leading exponents of classical I liberalism during the late nineteenth century. Few of those men, however, fore- saw the ultimate fate of their new party and of the philosophy of limited government that it championed. -

"Citizens in the Making": Black Philadelphians, the Republican Party and Urban Reform, 1885-1913

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2017 "Citizens In The Making": Black Philadelphians, The Republican Party And Urban Reform, 1885-1913 Julie Davidow University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Davidow, Julie, ""Citizens In The Making": Black Philadelphians, The Republican Party And Urban Reform, 1885-1913" (2017). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2247. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2247 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2247 For more information, please contact [email protected]. "Citizens In The Making": Black Philadelphians, The Republican Party And Urban Reform, 1885-1913 Abstract “Citizens in the Making” broadens the scope of historical treatments of black politics at the end of the nineteenth century by shifting the focus of electoral battles away from the South, where states wrote disfranchisement into their constitutions. Philadelphia offers a municipal-level perspective on the relationship between African Americans, the Republican Party, and political and social reformers, but the implications of this study reach beyond one city to shed light on a nationwide effort to degrade and diminish black citizenship. I argue that black citizenship was constructed as alien and foreign in the urban North in the last decades of the nineteenth century and that this process operated in tension with and undermined the efforts of black Philadelphians to gain traction on their exercise of the franchise. For black Philadelphians at the end of the nineteenth century, the franchise did not seem doomed or secure anywhere in the nation. -

Political Party Machines of the 1920S and 1930S: Tom Pendergast and the Kansas City Democratic Machine

Political Party Machines of the 1920s and 1930s: Tom Pendergast and The Kansas City Democratic Machine. BY JOHN S. MATLIN. A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Department of American and Canadian Studies, School of Historical Studies, University of Birmingham. September, 2009. Table of Contents. Page No. Acknowledgments. 3. Abstract. 5. Introduction. 6. Chapter 1. A Brief History of American Local Government until the end of the Nineteenth Century. 37. Chapter 2. The Fall and Rise of Political Party Machines in the Progressive Era. 51. Chapter 3. Theories of Political Party Machines and Their Core Elements. 81. Chapter 4. “Bossism”: The Need for Strong Leadership. 107. Chapter 5. Patronage: The Boss’s Political Capital and Private Profit. 128. Chapter 6. Challengers to the Machine: Rabbi Mayerberg, The Charter League and Fusion Movement. 145. Chapter 7. Challenges from the Press. The Self-Appointed Role of Newspapers as Moral Watchdogs. 164. Chapter 8. Corruption: Machines and Elections. 193. Chapter 9. Corruption: Machine Business, Organized Crime and the Downfall of Tom Pendergast. 219. Chapter 10. Political Party Machines: Pragmatism and Ethics. 251. Conclusion. 264. Bibliography. 277. 2 Acknowledgments It is a rare privilege to commence university life after retirement from a professional career. At the age of 58, I enrolled at Brunel University on an American Studies course, assuming that I would learn little that I did not already know. My legal life had taken me to many of the states of America numerous times over the previous forty years. My four years at Brunel as an undergraduate and post-graduate opened my eyes about the United States in a way I had not thought possible. -

Race, Party, and African American Politics, in Boston, Massachusetts, 1864-1903

Not as Supplicants, but as Citizens: Race, Party, and African American Politics, in Boston, Massachusetts, 1864-1903 by Millington William Bergeson-Lockwood A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in the University of Michigan 2011 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Martha S. Jones, Chair Professor Kevin K. Gaines Professor William J. Novak Professor Emeritus J. Mills Thornton III Associate Professor Matthew J. Countryman Copyright Millington William Bergeson-Lockwood 2011 Acknowledgements Writing a dissertation is sometimes a frustratingly solitary experience, and this dissertation would never have been completed without the assistance and support of many mentors, colleagues, and friends. Central to this project has been the support, encouragement, and critical review by my dissertation committee. This project is all the more rich because of their encouragement and feedback; any errors are entirely my own. J. Mills Thornton was one of the first professors I worked with when I began graduate school and he continues to make important contributions to my intellectual growth. His expertise in political history and his critical eye for detail have challenged me to be a better writer and historian. Kevin Gaines‘s support and encouragement during this project, coupled with his insights about African American politics, have been of great benefit. His push for me to think critically about the goals and outcomes of black political activism continues to shape my thinking. Matthew Countryman‘s work on African American politics in northern cities was an inspiration for this project and provided me with a significant lens through which to reexamine nineteenth-century black life and politics. -

Naval Documents of the American Revolution, Volume 11, Part 2

Naval Documents of The American Revolution Volume 11 AMERICAN THEATRE: Jan. 1, 1778–Mar. 31, 1778 EUROPEAN THEATRE: Jan. 1, 1778–Mar. 31, 1778 Part 2 of 5 United States Government Printing Office Washington, 2005 Electronically published by American Naval Records Society Bolton Landing, New York 2012 AS A WORK OF THE UNITED STATES FEDERAL GOVERNMENT THIS PUBLICATION IS IN THE PUBLIC DOMAIN. 1 FEBRUARY 1778 261 Past in the lower House [Hartford]/Feb 1778/ Test: AndwAdams Clerk.- D, Ct, Connecticut Archives, 1st Series, vol. 10, p. 112. February 1 (Sunday) [Boston] 1778 Feb. 1. The Ship1 fell down to Nantasket Road- DLC, Journal of Lieutenant William Jennison, p. 5. 1. Continental Navy frigate Boston, Captain Samuel Tucker, commander CAPTAINANDREW SNAPE HAMOND, R.N., TO VICEADMIRAL VISCOUNT HOWE Roebuck at Philadelphia My Lord, the lSt.February 1'778. The breaking up of the Frost has so much cleared the River of the Ice, that the Liuerpool is enabled to sail for New York for the Generals Dispatches arrived there in the three last Pacquets.-With the Liuerpool goes also a Mail for England in the Despenser Pacquet convoyed by two Armed Vessels.- Since your Lordships departure from hence no material event has happened except the loss of the Transport Brig Symetry one of the Baggage Vessels from New York,' which run a shore near Wilmington, and by the Frost coming on fell into the Enemy's hands before any Assistance could be sent from hence. Out of thirty Vessels that were taking in Forage at Tinnicum Island the 27h, DecemL when the Snow begun, -

LE II Student Textbook.Pdf

144279_LE_II_Student_Textbook_Cover.indd Letter V 8/6/19 5:30 AM LE-II TABLE OF CONTENTS Leadership Leadership Primary and Secondary Objectives ............................................................................................ 1 The 11 Leadership Principals ........................................................................................................................ 5 Authority, Responsibility, and Accountability ........................................................................................... 11 The Role of the NCO .................................................................................................................................. 15 The Role of an Officer ................................................................................................................................ 29 Motivational Principles and Techniques ..................................................................................................... 33 Maintaining High Morale ........................................................................................................................... 39 Marine Discipline ........................................................................................................................................ 43 Individual and Team Training..................................................................................................................... 47 Proficiency Defined ................................................................................................................................... -

General Bernardo De Galvez: a Lagniappe American Citizen In

General Bernardo de Galvez: a Lagniappe American Citizen In creole French Louisiana, Lagniappe is a southern term for "a little something extra" Its origin is from the Spanish word "la napa," meaning "something added." General Bernardo de Galvez y Madrid, Viscount ofGalveston and Count ofGalvez represents that "something extra" to Americans. The revered Spanish military officer served as a Colonel and Governor of Spanish-ruled Louisiana in 1776. Though a native Spaniard, Galvez also spoke French, which proved quite beneficial to him as Governor ofthe former French colony, Louisiana. And, despite his allegiance to Spain, Galvez expressed patriotic sentiments toward the revolutionary cause. First, Galvez risked his life, and those ofhis soldiers, to smuggle much-needed rations, medicine, ammunition and supplies, as well as critical military intelligence, to American troops garrisoned along the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers in 1777 - two years before Spain officially declared war against Great Britain. In addition, Galvez protected American patriots seeking refuge in Louisiana; he even prevented the British from capturing patriot James Willing, who had publicly conducted raids ofBritish forts and ships up and down the Mississippi River. Moreover, he routinely exchanged military information with American patriots, including George Washington, Patrick Henry, Thomas Jefferson, and Oliver Pollock, and thwarted British attempts to utilize the port ofNew Orleans and the Mississippi River. Most importantly, Galvez's strategic military success in securing British forces at Bayou Manchac (which officially represented Spain's involvement in the American Revolutionary War), Baton Rouge and the ports ofNatchez in 1779, Biloxi, New Orleans, and Mobile in 1780, and Pensacola in 1781 from the British greatly strengthened the allied forces' control ofthe East Coast.