Richard White Louisiana State University Ate in the Evening Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List for 202 First Exam

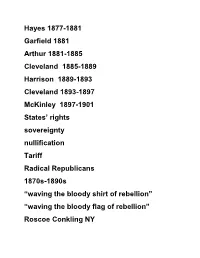

Hayes 1877-1881 Garfield 1881 Arthur 1881-1885 Cleveland 1885-1889 Harrison 1889-1893 Cleveland 1893-1897 McKinley 1897-1901 States’ rights sovereignty nullification Tariff Radical Republicans 1870s-1890s “waving the bloody shirt of rebellion” “waving the bloody flag of rebellion” Roscoe Conkling NY James G. Blaine Maine “Millionnaires’ Club” “the Railroad Lobby” 1. Conservative Rep party in control 2. Economy fluctuates a. Poor economy, prosperity, depression b. 1873 1893 1907 1929 c. Significant technological advances 3. Significant social changes 1876 Disputed Election of 1876 Rep- Rutherford B. Hayes Ohio Dem-Samuel Tilden NY To win 185 Tilden 184 + 1 Hayes 165 + 20 Fl SC La Oreg January 1877 Electoral Commission of 15 5 H, 5S, 5SC 7 R, 7 D, 1LR 8 to 7 Compromise of 1877 1. End reconstruction April 30, 1877 2. Appt s. Dem. Cab David Key PG 3. Support funds for internal improvements in the South Hayes 1877-1881 “ole 8 and 7 Hayes” “His Fraudulency” Carl Schurz Wm Everts Civil Service Reform Chester A. Arthur Great Strike of 1877 Resumption Act 1875 specie Bland Allison Silver Purchase Act 1878 16:1 $2-4 million/mo Silver certificates 1880 James G. Blaine Blaine Halfbreeds Rep James A Garfield Ohio Chester A. Arthur Roscoe Conkling Conkling Stalwarts Grant Dem Winfield Scott Hancock PA Greenback Party James B. Weaver Iowa Battle of the 3 Generals 1881 Arthur Pendleton Civil Service Act 1883 Chicago and Boston 1884 Election Rep. Blaine of Maine Mugwumps Dem. Grover Cleveland NY “Rum, Romanism and Rebellion” 1885-1889 Character Union Veterans Grand Army of the Republic GAR LQC Lamar S of Interior 1862 union pension 1887 Dependent Pension Bill Interstate Commerce Act 1887 ICC Pooling, rebates, drawbacks Prohibit discrimination John D. -

The Vice Presidential Bust Collection Brochure, S

Henry Wilson Garfield. Although his early political success had design for the American buffalo nickel. More than (1812–1875) ⓲ been through the machine politics of New York, 25 years after sculpting the Roosevelt bust, Fraser Daniel Chester French, Arthur surprised critics by fighting political created the marble bust of Vice President John 1886 corruption. He supported the first civil service Nance Garner for the Senate collection. THE Henry Wilson reform, and his administration was marked by epitomized the honesty and efficiency. Because he refused to Charles G. Dawes American Dream. engage in partisan politics, party regulars did not (1865–1951) VICE PRESIDENTIAL Born to a destitute nominate him in 1884. Jo Davidson, 1930 family, at age 21 he Prior to World War I, BUST COLLECTION Sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens originally walked to a nearby Charles Dawes was a declined to create Arthur’s official vice presidential town and began a lawyer, banker, and bust, citing his own schedule and the low business as a cobbler. Wilson soon embarked on politician in his native commission the Senate offered. Eventually he a career in politics, and worked his way from the Ohio. During the war, reconsidered, and delivered the finished work in Massachusetts legislature to the U.S. Senate. In a he became a brigadier politically turbulent era, he shifted political parties 1892. One of America’s best known sculptors, Saint-Gaudens also created the statue of Abraham general and afterwards several times, but maintained a consistent stand headed the Allied against slavery throughout his career. Wilson was Lincoln in Chicago’s Lincoln Park and the design reparations commission. -

The President Also Had to Consider the Proper Role of an Ex * President

************************************~ * * * * 0 DB P H0 F E8 8 0 B, * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * The little-known * * story of how * a President of the * United States, Beniamin Harrison, helped launch Stanford law School. ************************************* * * * T H E PRESIDENT * * * * * * * * * * * * By Howard Bromberg, J.D. * * * TANFORD'S first professor of law was a former President of the United * States. This is a distinction that no other school can claim. On March 2, 1893, * L-41.,_, with two days remaining in his administration, President Benjamin Harrison * * accepted an appointment as Non-Resident Professor of Constitutional Law at * Stanford University. * Harrison's decision was a triumph for the fledgling western university and its * * founder, Leland Stanford, who had personally recruited the chief of state. It also * provided a tremendous boost to the nascent Law Department, which had suffered * months of frustration and disappointment. * David Starr Jordan, Stanford University's first president, had been planning a law * * program since the University opened in 1891. He would model it on the innovative * approach to legal education proposed by Woodrow Wilson, Jurisprudence Profes- * sor at Princeton. Law would be taught simultaneously with the social sciences; no * * one would be admitted to graduate legal studies who was not already a college * graduate; and the department would be thoroughly integrated with the life and * * ************************************** ************************************* * § during Harrison's four difficult years * El in the White House. ~ In 1891, Sena tor Stanford helped ~ arrange a presidential cross-country * train tour, during which Harrison * visited and was impressed by the university campus still under con * struction. When Harrison was * defeated by Grover Cleveland in the 1892 election, it occurred to Senator * Stanford to invite his friend-who * had been one of the nation's leading lawyers before entering the Senate * to join the as-yet empty Stanford law * faculty. -

Uniting Mugwumps and the Masses: the Role of Puck in Gilded Age Politics, 1880-1884

Uniting Mugwumps and the Masses: The Role of Puck in Gilded Age Politics, 1880-1884 Daniel Henry Backer McLean, Virginia B.A., University of Notre Dame, 1994 A Thesis presented to 1he Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of English University of Virginia August 1996 WARNING! The document you now hold in your hands is a feeble reproduction of an experiment in hypertext. In the waning years of the twentieth century, a crude network of computerized information centers formed a system called the Internet; one particular format of data retrieval combined text and digital images and was known as the World Wide Web. This particular project was designed for viewing through Netscape 2.0. It can be found at http://xroads.virginia.edu/~MA96/PUCK/ If you are able to locate this Website, you will soon realize it is a superior resource for the presentation of such a highly visual magazine as Puck. 11 Table of Contents Introduction 1 I) A Brief History of Cartoons 5 II) Popular and Elite Political Culture 13 III) A Popular Medium 22 "Our National Dog Show" 32 "Inspecting the Democratic Curiosity Shop" 35 Caricature and the Carte-de-Viste 40 The Campaign Against Grant 42 EndNotes 51 Bibliography 54 1 wWhy can the United States not have a comic paper of its own?" enquired E.L. Godkin of The Nation, one of the most distinguished intellectual magazines of the Gilded Age. America claimed a host of popular and insightful raconteurs as its own, from Petroleum V. -

Gold Democrats and the Decline of Classical Liberalism, 1896–1900

SUBSCRIBE NOW AND RECEIVE CRISIS AND LEVIATHAN* FREE! “The Independent Review does not accept “The Independent Review is pronouncements of government officials nor the excellent.” conventional wisdom at face value.” —GARY BECKER, Noble Laureate —JOHN R. MACARTHUR, Publisher, Harper’s in Economic Sciences Subscribe to The Independent Review and receive a free book of your choice* such as the 25th Anniversary Edition of Crisis and Leviathan: Critical Episodes in the Growth of American Government, by Founding Editor Robert Higgs. This quarterly journal, guided by co-editors Christopher J. Coyne, and Michael C. Munger, and Robert M. Whaples offers leading-edge insights on today’s most critical issues in economics, healthcare, education, law, history, political science, philosophy, and sociology. Thought-provoking and educational, The Independent Review is blazing the way toward informed debate! Student? Educator? Journalist? Business or civic leader? Engaged citizen? This journal is for YOU! *Order today for more FREE book options Perfect for students or anyone on the go! The Independent Review is available on mobile devices or tablets: iOS devices, Amazon Kindle Fire, or Android through Magzter. INDEPENDENT INSTITUTE, 100 SWAN WAY, OAKLAND, CA 94621 • 800-927-8733 • [email protected] PROMO CODE IRA1703 Gold Democrats and the Decline of Classical Liberalism, 1896–1900 —————— ✦ —————— DAVID T. BEITO AND LINDA ROYSTER BEITO n 1896 a new political party was born, the National Democratic Party (NDP). The founders of the NDP included some of the leading exponents of classical I liberalism during the late nineteenth century. Few of those men, however, fore- saw the ultimate fate of their new party and of the philosophy of limited government that it championed. -

"Citizens in the Making": Black Philadelphians, the Republican Party and Urban Reform, 1885-1913

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2017 "Citizens In The Making": Black Philadelphians, The Republican Party And Urban Reform, 1885-1913 Julie Davidow University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Davidow, Julie, ""Citizens In The Making": Black Philadelphians, The Republican Party And Urban Reform, 1885-1913" (2017). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2247. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2247 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2247 For more information, please contact [email protected]. "Citizens In The Making": Black Philadelphians, The Republican Party And Urban Reform, 1885-1913 Abstract “Citizens in the Making” broadens the scope of historical treatments of black politics at the end of the nineteenth century by shifting the focus of electoral battles away from the South, where states wrote disfranchisement into their constitutions. Philadelphia offers a municipal-level perspective on the relationship between African Americans, the Republican Party, and political and social reformers, but the implications of this study reach beyond one city to shed light on a nationwide effort to degrade and diminish black citizenship. I argue that black citizenship was constructed as alien and foreign in the urban North in the last decades of the nineteenth century and that this process operated in tension with and undermined the efforts of black Philadelphians to gain traction on their exercise of the franchise. For black Philadelphians at the end of the nineteenth century, the franchise did not seem doomed or secure anywhere in the nation. -

Charles W. Fairbanks Letter, 17 February 1899

Collection # SC 2640 CHARLES W. FAIRBANKS LETTER, 17 FEBRUARY 1899 Collection Information Biographical Sketch Scope and Content Note Cataloging Information Processed by Chris Harter 31 December 1997 Revised 16 May 2002 Updated 9 March 2004 Manuscript and Visual Collections Department William Henry Smith Memorial Library Indiana Historical Society 450 West Ohio Street Indianapolis, IN 46202-3269 www.indianahistory.org COLLECTION INFORMATION VOLUME OF 1 folder COLLECTION: COLLECTION 17 February 1899 DATES: PROVENANCE: Remember When Auctions, P.O. Box 1829, Wells, ME 04090, 24 October 1997 RESTRICTIONS: None COPYRIGHT: REPRODUCTION Permission to reproduce or publish material in this collection RIGHTS: must be obtained from the Indiana Historical Society. ALTERNATE None FORMATS: RELATED M 0100, Charles Warren Fairbanks Papers; BV 1150–1169, HOLDINGS: Charles W. Fairbanks Collection; SC 0550, William E. English Will and Testament; SC 1654, William E. English Letter ACCESSION 1998.0038 NUMBER: NOTES: BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH Charles Warren Fairbanks (1852–1918), the son of Lorsiton M. and Mary A. (Smith) Fairbanks, was born in a log cabin near Unionville Center, Ohio. He graduated from Ohio Wesleyan University in 1872, and three years later received a master's degree from the same institution. Through the influence of his uncle William Henry Smith he obtained a position with the Associated Press, serving in its Pittsburgh and Cleveland offices from 1872 to 1874. At the same time he managed to study law and to be admitted to the bar in 1874. In the same year he married Cornelia Cole (1852–1913), a college classmate, and moved to Indianapolis. They had five children: Adelaide (1875 or 1876– 1961), Warren Charles (1878–1938), Frederick C. -

The Prez Quiz Answers

PREZ TRIVIAL QUIZ AND ANSWERS Below is a Presidential Trivia Quiz and Answers. GRADING CRITERIA: 33 questions, 3 points each, and 1 free point. If the answer is a list which has L elements and you get x correct, you get x=L points. If any are wrong you get 0 points. You can take the quiz one of three ways. 1) Take it WITHOUT using the web and see how many you can get right. Take 3 hours. 2) Take it and use the web and try to do it fast. Stop when you want, but your score will be determined as follows: If R is the number of points and T 180R is the number of minutes then your score is T + 1: If you get all 33 right in 60 minutes then you get a 100. You could get more than 100 if you do it faster. 3) The answer key has more information and is interesting. Do not bother to take the quiz and just read the answer key when I post it. Much of this material is from the books Hail to the chiefs: Political mis- chief, Morals, and Malarky from George W to George W by Barbara Holland and Bland Ambition: From Adams to Quayle- the Cranks, Criminals, Tax Cheats, and Golfers who made it to Vice President by Steve Tally. I also use Wikipedia. There is a table at the end of this document that has lots of information about presidents. THE QUIZ BEGINS! 1. How many people have been president without having ever held prior elected office? Name each one and, if they had former experience in government, what it was. -

Inaugural History

INAUGURAL HISTORY Here is some inaugural trivia, followed by a short description of each inauguration since George Washington. Ceremony o First outdoor ceremony: George Washington, 1789, balcony, Federal Hall, New York City. George Washington is the only U.S. President to have been inaugurated in two different cities, New York City in April 1789, and his second took place in Philadelphia in March 1793. o First president to take oath on January 20th: Franklin D. Roosevelt, 1937, his second inaugural. o Presidents who used two Bibles at their inauguration: Harry Truman, 1949, Dwight D. Eisenhower, 1953, George Bush, 1989. o Someone forgot the Bible for FDR's first inauguration in 1933. A policeman offered his. o 36 of the 53 U.S. Inaugurations were held on the East Portico of the Capitol. In 1981, Ronald Reagan was the first to hold an inauguration on the West Front. Platform o First platform constructed for an inauguration: Martin Van Buren, 1837 [note: James Monroe, 1817, was inaugurated in a temporary portico outside Congress Hall because the Capitol had been burned down by the British in the War of 1812]. o First canopied platform: Abraham Lincoln, 1861. Broadcasting o First ceremony to be reported by telegraph: James Polk, 1845. o First ceremony to be photographed: James Buchanan, 1857. o First motion picture of ceremony: William McKinley, 1897. o First electronically-amplified speech: Warren Harding, 1921. o First radio broadcast: Calvin Coolidge, 1925. o First recorded on talking newsreel: Herbert Hoover, 1929. o First television coverage: Harry Truman, 1949. [Only 172,000 households had television sets.] o First live Internet broadcast: Bill Clinton, 1997. -

Political Party Machines of the 1920S and 1930S: Tom Pendergast and the Kansas City Democratic Machine

Political Party Machines of the 1920s and 1930s: Tom Pendergast and The Kansas City Democratic Machine. BY JOHN S. MATLIN. A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Department of American and Canadian Studies, School of Historical Studies, University of Birmingham. September, 2009. Table of Contents. Page No. Acknowledgments. 3. Abstract. 5. Introduction. 6. Chapter 1. A Brief History of American Local Government until the end of the Nineteenth Century. 37. Chapter 2. The Fall and Rise of Political Party Machines in the Progressive Era. 51. Chapter 3. Theories of Political Party Machines and Their Core Elements. 81. Chapter 4. “Bossism”: The Need for Strong Leadership. 107. Chapter 5. Patronage: The Boss’s Political Capital and Private Profit. 128. Chapter 6. Challengers to the Machine: Rabbi Mayerberg, The Charter League and Fusion Movement. 145. Chapter 7. Challenges from the Press. The Self-Appointed Role of Newspapers as Moral Watchdogs. 164. Chapter 8. Corruption: Machines and Elections. 193. Chapter 9. Corruption: Machine Business, Organized Crime and the Downfall of Tom Pendergast. 219. Chapter 10. Political Party Machines: Pragmatism and Ethics. 251. Conclusion. 264. Bibliography. 277. 2 Acknowledgments It is a rare privilege to commence university life after retirement from a professional career. At the age of 58, I enrolled at Brunel University on an American Studies course, assuming that I would learn little that I did not already know. My legal life had taken me to many of the states of America numerous times over the previous forty years. My four years at Brunel as an undergraduate and post-graduate opened my eyes about the United States in a way I had not thought possible. -

Benjamin Harrison the President As Conservationist

Benjamin Harrison The president as conservationist EPISODE TRANSCRIPT Listen to Presidential at http://wapo.st/presidential This transcript was run through an automated transcription service and then lightly edited for clarity. There may be typos or small discrepancies from the podcast audio. LILLIAN CUNNINGHAM: It's that time in the American presidency when we have reached the age of recordings, and our subject this week, Benjamin Harrison, is the first president whose voice we can hear. It sounds like this: VOICE OF BENJAMIN HARRISON LILLIAN CUNNINGHAM: So, not very clear at all, but it's a start. This was recorded on an Edison wax cylinder sometime around Harrison's first year in office in 1889. Also in this year, the Coca-Cola Company was created, and the first jukebox went into use in San Francisco. It's the end of the 19th century and technology and industrialization are reshaping America. And amid all this excitement and the many benefits of innovation, there are also new fears and questions emerging among citizens that presidents have to address about who might be left behind in this process and what in our country might be getting destroyed. I'm Lillian Cunningham with The Washington Post, and this is the 23rd episode of “Presidential.” PRESIDENTIAL THEME MUSIC LILLIAN CUNNINGHAM: Benjamin Harrison was born in Indiana in 1833. He was one of 13 children, and he served as president from 1889 until 1893 -- so right smack in the middle of Grover Cleveland's two terms. The history books today barely even mention Benjamin Harrison, though, and when they do, the write-ups are usually not too praising. -

The Story of the US Postal Service

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 281 820 SO 018 202 TITLE We Deliver: The Story of the U.S. Postal Service. INSTITUTION Postal Service, Washington, DC. PUB DATE 80 NOTE 25p.; Illustrations will not reproduce clearly. PUB TYPE Historical Materials (060) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Government Employees; Government Role; *Public Agencies;_ United States History IDENTIFIERS *PoStal Service ABSTRACT This eight-chapter illustrated booklet chronicles the history of the U.S. Post Office from its establishment by the Continental Congress in 1775 to the present. Chapter 1, "The Colonists," describes the postal service before the Revolutionary War. Benjamin Franklin's appointment as the first Postmaster General of the U.S. and his many contributions to the postal serviceare covered in Chapter 2, "Father of the U.S. Postal Service." Chapter 3, "The Revolution and After," portrays the huge increase that occurred in the U.S. population from the time of Andrew Jackson to the Civil War, the resulting huge increase in mail volume that occurred, and the actions the postal system took to overcome the problems. In Chapter 4, "The Pony Express," the 18-month life span of the pony express is chronicled as are the reasons for its demise. Two Postmaster Generals, Montgomery Blair and John Wanamaker, are portrayed in Chapter 5, "Two Postal Titans." These two men provided leadership which resulted in improved employee attitudes and new services to customers, such as free rural delivery and pneumatic tubes. Chapter 6, "Postal Stamps," tells the history of the postage stamp, and how a stamp is developed. Chapter 7, "Moving the Mail," presents a history of the mail service and the different modes of transportation on which it depends.