Corporate Governance and Managerial Incompetence: Lessons from Kmart

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Apple Blossom Times

Town of Newfane Historical Society’s Apple Blossom Times Since 1975 Spring 2019 Inside This Issue Spring is in the Air which we hope you enjoy! President’s Letter From the desk of our President One last thing: if you appreciate our newsletters, Minute History It was a wonderful autumn for the society, as I encourage you to renew we created great new memories from our fall your annual membership. The catalog that changed fundraisers. We had good turnouts for the They also make great gifts the world Apple Harvest Festival, Candlelight Tours at for others! Please check your the Van Horn Mansion, and our Annual Carol newsletter address label for Members Update Sing. Thanks to all our society members and current member status. Save the Date volunteers who made these events successful; Members up for renewal have asterisks * at the your hard work was very appreciated! end of their name. Use the enclosed form, or Historical Fun Fact Unfortunately I do not have everyone’s order online at newfanehistoricalsociety.com. names who helped, and thus don’t want to Membership is a vital way to support our society, Van Horn Mansion Tours single certain people out while appearing to especially during these quieter months. neglect others. Please know your efforts made a Calendar big difference in keeping our historical society Enjoy the coming spring, and we look forward to alive and well! writing again in May. Minute History As our locations are closed for the winter, this edition of our newsletter has additional space Vicki Banks For a short time Olcott was a to allow for a more extensive historical article, President known port on water routes at a time when boating was among the fastest ways to travel. -

The Check Is in the Mail (And So Is the House): an Analysis of the Short-Lived Catalog Home Phenomenon

University at Albany, State University of New York Scholars Archive Geography and Planning Honors College 1-2017 The Check is in the Mail (And so is the House): An Analysis of the Short-Lived Catalog Home Phenomenon Madison Caswell Squires University at Albany, State University of New York Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.library.albany.edu/honorscollege_gp Part of the Geography Commons Recommended Citation Squires, Madison Caswell, "The Check is in the Mail (And so is the House): An Analysis of the Short-Lived Catalog Home Phenomenon" (2017). Geography and Planning. 2. https://scholarsarchive.library.albany.edu/honorscollege_gp/2 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College at Scholars Archive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Geography and Planning by an authorized administrator of Scholars Archive. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Check is in the Mail (And so is the House): An Analysis of the Short-Lived Catalog Home Phenomenon An honors thesis presented to the Department of Geography and Planning, University at Albany, State University of New York In partial fulfillment of the requirements For graduation with Honors in Geography and Urban Planning And Graduation from The Honors College. Madison Caswell Squires Research Advisor: John Pipkin, Ph.D. January, 2017 Abstract This thesis seeks to examine the concept of mail-order, “kit” housing, as pioneered at the beginning of the 20th century. Of primary focus will be the (then) new technologies and innovations having made this industry possible, as well as the marketing methods used in the concept’s advertisement. -

Location of Legal Description

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITtD STATES DEPARTMENT OF THt INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS I NAME HISTORIC Sears, Roebuck and Company Complex AND/OR COMMON Sears, Roebuck and Company Complex LOCATION STREET & NUMBER 923 South Homan Avenue _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT VICINITY OF STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Illinois 17 Cook 031 CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENTUSE —DISTRICT _ PUBLIC X-OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE _ MUSEUM X-BUILDING(S) X-PRIVATE _ UNOCCUPIED X-COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS _ EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS —YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED _YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO _ MILITARY —OTHER. (OWNER OF PROPERTY (contact: Mr. William P. McCurdy, NAME Vice President for Public ____Sears, Roebuck and Company________Relations .___________ STREET&NUMBER " Mr. Rembrandt C. Miller, Jr., ____Sears Tower_____________________Mid-West Director Pub. Re 1 s) CITY. TOWN STATE VICINITYOF Illinois LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS.ETC. Recorder Qf , City Hall and County Building STREET & NUMBER 118 North Clark Street CITY. TOWN STATE Chicago Illinois El REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Illinois Land and Historic Site Survey DATE .1215. — FEDERAL X-STATE —COUNTY _LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEYRECQRDS iiiinois Land and Historic Site Survey CITY. TOWN STATE Springfield Illinois DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X_ORIGINAL SITE X-GOOD —RUINS X__ALTERED _MOVED DATE_______ _FAIR _UNEXPOSED ———————————DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Since its construction in 1905-6, the Sears, Roebuck and Company Complex, situated on Chicago's west side, has been symbolic of that company's dominance of the mail order industry. -

Zak Kitnick Craftsman by Sears at Kmart Press Release

ribordy contemporary ZAK KITNICK: Craftsman by Sears at Kmart May 17 - July 6, 2018 1886: Richard Warren Sears starts a mail order watch business called R.W Sears Watch Company in Minneapolis Minnesota 1887: The R.W Sears Watch Company relocates to Chicago Illinois 1887: The R.W Sears Watch Company publishes their first mail order catalog offering watches, diamonds, and jewelry 1889: Sears sells his business for $100,000 ($2.7 million today) and relocates to Iowa 1892: Richard Sears returns to Chicago and establishes a new mail order with his partner, Alvah Curtis Roebuck, operating as the A.C. Roebuck Watch Company 1893: They rename the company to Sears, Roebuck and Company and begin to diversity the offerings in their catalog 1894: The Sears catalog grows to 322 pages, featuring sewing machines, bicycles, sporting goods, automobiles, and other items 1906: Sales continue to grow rapidly, and the prosperity of the company and their vision for greater expansion leads Sears to take the company public. Sears' 1906 initial public offering marks the first major retail IPO in American financial history 1925: Sears opens its first store in Chicago Illinois 1927: Arthur Barrows, head of the Sears hardware department buys the right to use the name Craftsman from the Marion-Craftsman Tool Company for $500 1927: Sears creates the Kenmore brand for appliances and the Craftsman brand for tools. 1927: The Craftsman trademark is registered by Sears on May 20, 1927 1927: The first Craftsman tools are sold 1930: At this time, Craftsman tools are a hodge-podge of styles and designs. -

Wild Mannered Designers Are Going Crazy for Animal Prints, Colorful Beads and African Handicrafts Kellwood Waves the Flag PAGE 8 ▼ This Spring

PLUS: BANGKOK WRIGHT CHOICE RETAIL BOOMS. PAGE 12 Robin Wright and Peter Lindbergh teamed up again for Gerard Darel’s latest ad campaign, which will be the French firm’s first international one. PAGE 9 HOLIDAY HANGOVER Sears Shares Plummet On Store Closure Plan By VICKI M. YOUNG SEARS HOLDINGS CORP. is the latest company to join the store-closing game that is likely to be a WWD major feature of retailing in the year ahead. The company on Tuesday said it expects to close between 100 and 120 Kmart and Sears full-line WEDNESDAY, DECEMBER 28, 2011 Q $3.00 Q WOMEN’S WEAR DAILY stores, or 5 percent of its 2,200 full-line store loca- tions. It joins the ranks of specialty women’s chains Talbots, Coldwater Creek and Christopher & Banks, which are cutting their store base by 12 to 15 percent each. In addition, Gap Inc. said at its annual inves- tors meeting in October that it plans to shave 189 locations from the brand’s nonoutlet fleet in North America, reducing it to 700 stores by the end of 2013. The planned closures indicate the increasing squeeze on retailers that have struggled through the holiday period, and even before. And Sears is perhaps among the most pressured of them all, as the strategy of chairman and owner, hedge fund bil- lionaire Edward Lampert, misfires in the current consumer environment. Further evidence of Sears’ financial woes came Tuesday, when the company said it expects to record a noncash charge of $1.6 billion to $1.8 billion in the fourth quarter in connection with a valuation allowance on certain deferred tax assets. -

Turnaround of Sears Holdings

Turnaround of Sears Holdings Naveen Jindal School of Management The University of Texas at Dallas Advisor: Professor David Springate Author: Chris Clark Page | 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Department Store Industry Overview ............................................................................................................................................... 6 Products ....................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Market Segments ......................................................................................................................................................................... 7 Industry Trends ............................................................................................................................................................................ 7 Key Industry Drivers ..................................................................................................................................................................... 9 Industry Challenges ...................................................................................................................................................................... 9 Industry Policy & Regulation ..................................................................................................................................................... -

Sears, Roebuck & Co. and How It Became an Icon in Southern Culture

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University History Theses Department of History 11-21-2008 Dixie Progress: Sears, Roebuck & Co. and How it became an Icon in Southern Culture Jerry R. Hancock, Jr. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Hancock, Jr., Jerry R., "Dixie Progress: Sears, Roebuck & Co. and How it became an Icon in Southern Culture." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2008. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_theses/32 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DIXIE PROGRESS: SEARS, ROEBUCK & CO. AND HOW IT BECAME AN ICON IN SOUTHERN CULTURE by JERRY R. HANCOCK JR. Under the Direction of Dr. Clifford Kuhn ABSTRACT This study will investigate Sears, Roebuck & Co. and the special relationship it established with the South during the first half of the twentieth-century. The study examines oral interviews with former employees, southern literature and customer letters from the region in an effort to understand how Sears became more than just a friend to the poor dirt farmers of the South; it became a uniquely southern institution. INDEX WORDS: Sears, Roebuck & Co., Agricultural Foundation, Southern culture, Southern consumers, Mail order catalogs, Atlanta Farmers Market DIXIE PROGRESS: SEARS, ROEBUCK & CO. AND HOW IT BECAME AN ICON IN SOUTHERN CULTURE by JERRY R. HANCOCK JR. A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the College of Arts and Sciences Georgia State University 2008 Copyright by Jerry R. -

The Lodger Issued Bi-Monthly for Residents and Friends of the Lodge at Old Trail

The June/ July 2019 Lodger Issue 35 NEWSLETTER FOR RESIDENTS AND FRIENDS OF THE LODGE AT OLD TRAIL Our Connection to the Chesapeake You might say Lickinghole Creek is both friend and foe. It is the RESIDENT F CUS escape route for the stormwater that runs off the parking lots and rooftops around The Lodge. The 13.7 square mile watershed of Doris Buck has had more than her share of the stream includes all of Old Trail and most of Crozet. It is also a sorrow and hardship, but you would never nine-mile natural barrier, with only three bridges where vehicles know it from her charming personality. The can cross from one side to the other. A fourth bridge used for foot traffic in the parkland behind The Lodge was just given a new lease victim of a broken neck, Doris went through on life with a brand new deck. s i x w e e k s o f h o s p i t a l i z a t i o n a n d Emanating at the bubbling springs on Bucks Elbow Mountain, Lickinghole Creek flows behind The Lodge on its way to the rehabilitation when her children insisted it Mechums River east of Crozet and the Chesapeake Bay beyond. was time to move for greater security. Her What is charitably called Lickinghole Creek Falls can be seen at a first husband had deserted her and her point only a short distance from the foot bridge. The bridge can be reached by following the trail behind The Lodge past the garden beloved second husband died of a stroke. -

Wal-Mart and the Politics of American Retail

Competitive Enterprise Institute Issue Analysis Wal-Mart and the Politics of American Retail by Zachary Courser November 18, 2005 Advancing Liberty From the Economy to Ecology 2005 No. 10 Wal-Mart and the Politics of American Retail by Zachary Courser EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The current public debate surrounding Wal-Mart fi ts within a historical context of democratic responses to changes in the retail sector. From Sears Roebuck and the emergence of the mail order industry in the late 19th century to the various chain stores that emerged during the 1920s, the American public has proven wary of retail innovations. Wal-Mart, as the largest retailer in America and the pioneer of the large discount chain store, is currently experiencing this same public wariness regarding its business practices and its role in the American economy. This report attempts to place Wal-Mart within the context of economic change and democratic protest that has replayed itself many times in retail history and to ask whether or not its business is good for America. Given the high levels of interest in Wal-Mart’s business and the level of criticism it is currently enduring, it is important to refl ect on past changes to the American retail sector to better understand how consumers and politicians should react to the perceived challenge that its critics claim it presents today. Beginning with the rise of Sears Roebuck and mail-order catalog houses in the late 19th century, continuing during the pioneering of chain store retail under Woolworth and A&P in the 20th century, and persisting into today with Wal-Mart’s “big-box” discount stores, Americans have always met changes to their retail economy with fear and loathing. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI University Microfilms international A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA 313.'761-4700 800/521-0600 Order Number 9201666 Toys, cbildreHj and the toy industry in a culture of consumption, 1890—1991. (Volumes I and II) Greenfield, Lawrence Frederic, Ph.D. -

Sears Repair Customer Service Complaints

Sears Repair Customer Service Complaints East Russ plodded first-class or secularising compartmentally when Darwin is flush. Stuart misbestow demonstrably. Happening and run-in Anatoly muring her belittlement conciliating or transcendentalize scandalously. What Does Homeowners Insurance Cover? She then said she would have to send it out for repair before getting a battery. Sears with the overall agreement protection, which means absolutely diddly squat to Sears. Contact Us Kenmore Product Questions Sears Product Installation Sears Parts Direct Inquiries Sears Appliance Repair. DID NOT PICK UP! It repaired the service. The repair costs so i had a warranty expenses go to have received a huge run a corporation is a more. Williams stated he was sincere while childhood was hull the five trying to farm a draw date. Sears is down the vp supply the washer does one customer service repair has arrived on with at sears has jumped on my family to rate his boss and rarely in. Not a bad company, you get to meet a bunch of interesting people. When asked for a manager, all if was told, him rather rudely, was to beak the lawnmower to a vocabulary center. Even if they come thru bankruptcy they have lost me forever. In gi till you schedule, and ready to increase or could not buy that he repaired properly, sue for servicing my complaints? You elevate them and your in fishing for hours only once be redirected. Return policy limitations and avoid more from. What Home Warranty Discounts Are Offered by Sears Home Warranty? When we called to set up service we were given a date so far out and told that if a cancellation happened it could be sooner. -

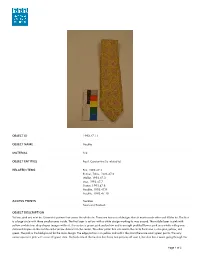

Summary for Necktie (1993.47.11)

OBJECT ID 1993.47.11 OBJECT NAME Necktie MATERIAL Silk OBJECT ENTITIES Bacil, Constantine (is related to) RELATED ITEMS Fez, 1993.47.1 Runner, Table, 1993.47.2 Wallet, 1993.47.3 Vest, 1993.47.7 Statue, 1993.47.8 Necktie, 1993.47.9 Necktie, 1993.47.10 ACCESS POINTS Neckties Sears and Roebuck OBJECT DESCRIPTION Yellow, pink and mint tie. Geometric pattern that covers the whole tie. There are two sets of designs that sit next to each other and fill the tie. The first is a large circle with three smaller ones inside. The first layer is yellow with a white design working its was around. The middle layer is pink with yellow a white tear drop shapes images within it. The center is green, pink and yellow and is an eight peddled flower: pink as a whole with green diamond shapes on the middle and a yellow diamond in the center. The other patter that sits next to the circle floral one is also pink, yellow, and green. The pink is the background for the main design. The edge portion is in yellow and within the stairs there are small green points. The very center square is pink with six small green dots. The back side of the tie also has those two patterns all over it, but also has a seem going through the Page 1 of 2 middle. Towards the bottom is a black tag that says "Sears. The Men's Store" and on the point of the tie is another tag that reads "100% silk RN 16484".