Sears, Roebuck & Company District Best.Pub

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0046 (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property ____ __ historic name Sears, Roebuck and Company Mail-Order Warehouse and Retail Store other names/site number Midtown Exchange 2. Location street & number 2929 Chicago Avenue South N/A D not for publication city or town Minneapolis N/A D vicinity state Minnesota code MN county Hennepin code 053 zip code 55407 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this ^nomination D request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property E3 meets D does not meet the National Register Criteria. -

Kenmore Appliance Warranty Master Protection Agreements One Year Limited Warranty Congratulations on Making a Smart Purchase

Kenmore Appliance Warranty Master Protection Agreements One Year Limited Warranty Congratulations on making a smart purchase. Your new Ken- When installed, operated and maintained according to all more® product is designed and manufactured for years of instructions supplied with the product, if this appliance fails due dependable operation. But like all products, it may require to a defect in material or workmanship within one year from the preventive maintenance or repair from time to time. That’s when date of purchase, call 1-800-4-MY-HOME® to arrange for free having a Master Protection Agreement can save you money and repair. aggravation. If this appliance is used for other than private family purposes, The Master Protection Agreement also helps extend the life of this warranty applies for only 90 days from the date of pur- your new product. Here’s what the Agreement* includes: chase. • Parts and labor needed to help keep products operating This warranty covers only defects in material and workman- properly under normal use, not just defects. Our coverage ship. Sears will NOT pay for: goes well beyond the product warranty. No deductibles, no functional failure excluded from coverage – real protection. 1. Expendable items that can wear out from normal use, • Expert service by a force of more than 10,000 authorized including but not limited to fi lters, belts, light bulbs and bags. Sears service technicians, which means someone you can 2. A service technician to instruct the user in correct product trust will be working on your product. installation, operation or maintenance. • Unlimited service calls and nationwide service, as often as 3. -

What Went Wrong with Kmart?

What Went Wrong With Kmart? An Honors Thesis (HONRS 499) by Jacqueline Matyk Thesis Advisor Dr. Mark Myring Ball State University Muncie, Indiana December 2003 Graduation: December 21, 2003 Table of Contents Abstract. ........... ..................................................... 3 Introduction ................................................................................ 4 History ofKnlart .......................................................................... 4 Overview ofKnlart ................................... .................................. 6 Kmart's Problems That Led to Bankruptcy ....... ............... 6 Major Troubles in 2001 .................................................................. 7 2002 and Bankruptcy ..................................................................... 9 Anonymous Letters Lead to Stewardship Review .................................... 9 Emergence from Bankruptcy........................................................... 12 Charles Conaway's Role ................................................................ 14 The Case Against Enio Montini and Joseph Hofmeister ........................... 17 Conclusion.. ............................................................................. 19 Works Cited ............................................................................. 20 2 Abstract This paper provides an in depth look at Krnart Corporation. I will discuss how the company began its operations as a small five and dime store in Michigan and grew into one of the nation's largest retailers. -

GENERAL GROWTH PROPERTIES, INC. 2001 Annual Report on Behalf of All the Employees Of

GENERAL GROWTH PROPERTIES, INC. 2001 annual report On behalf of all the employees of General Growth Properties, I would like to extend our condolences to anyone who lost a loved one, a friend, an acquaintance or a co-worker in The regional mall business is about relationships. the tragedy of September 11, 2001. We do not forge them lightly, but with the intent We are a country of strong individuals to nurture and strengthen them over time. Even in periods of distress, the relationships with who will continue to unite as we have rock solid our consumers, owners, retailers, and employees keep throughout our history.We will not us rooted in one fundamental belief: that success can be achieved allow horrific acts of terrorism to destroy when we work together.The dynamics of our the greatest and most powerful nation industry dictate that sustainability is contingent upon in the world. God bless you. the integrity of our business practices.We will never lose sight of this fact and will carry out every endeavor to reflect the highest standards. contents Financial Highlights . lift Portfolio . 12 Company Profile . lift Financial Review . 21 Operating Principles . 2 Directors and Officers . 69 Shareholders’ Letter . 4 Corporate Information . 70 Shopping Centers Owned at year end includes Centermark 1996 75 company profile General Growth Properties and its predecessor companies 1997 64 have been in the shopping center business for nearly fifty years. It is the second largest regional 1998 84 mall Real Estate Investment Trust (REIT) in the United States. General Growth owns, develops, 1999 93 operates and/or manages shopping malls in 39 states. -

Scrip Order Form

St. Thomas Aquinas SCRIP ORDER FORM Thank you! Your support is greatly appreciated! Please remember that we can sell only the amounts listed on the order form. Name:_______________________________________________Phone:___________________Date:_______________ Check# :_________________Amount:__________________ * Please make checks payable to: St. Thomas Aquinas * Filled by__________NEEDS:________________________________________________________________________ Retailer Profit Card Qty. Total Retailer Profit Card Qty. Total (c.o.a.) = certificate on account for Amount (c.o.a.) = certificate on for Amount school account school $5.00 $100 Claire’s $0.90 $10 All Seasons Gutter/New All Seasons Gutter/Topper $10.00 $100 Cold Stone $0.80 $10 Creamery American Eagle Outfitters $2.00 $25 Courtyard/Marriott $6.00 $50 Applebees $2.00 $25 Critter $0.50 $10 Nation(Dyvig’s) Arby’s $0.80 $10 Barnes & Noble/B. Dalton $1.00 $10 Derry Auto (c.o.a.) $1.00 $25 Barnes & Noble/B. Dalton $2.50 $25 Derry Auto (c.o.a.) $2.50 $50 Bath and Body Works $1.30 $10 Derry Auto (c.o.a.) $5.00 $100 Bath and Body Works $3.25 $25 Dillard’s $2.25 $25 Bed, Bath and Beyond $1.75 $25 Dress Barn $2.00 $25 Best Buy $0.50 $25 Express $2.50 $25 Best Buy $2.00 $100 Fareway $0.50 $25 Big Time Cinema (Fridley’s) $1.00 $10 Fareway $1.00 $50 Borders/Waldenbooks $0.90 $10 Fareway $2.00 $100 Borders/Waldenbooks $2.25 $25 Fairfield Inn/Marriott $6.00 $50 Build-A-Bear $2.00 $25 Fazoli’s $1.75 $25 Burger King $0.50 $10 Finish Line $2.50 $25 Cabela’s $3.25 $25 Flower Cart (c.o.a.) $1.25 $25 Carlos O’Kelly $0.90 $10 Foot Locker $2.25 $25 Casey’s $0.30 $10 Fuhs Pastry $1.00 $10 Casey’s $0.75 $25 Gap/Old $2.25 $25 Navy/Banana Republic Casey’s $1.50 $50 GameStop $0.75 $25 Cheesecake Factory $1.25 $25 Gerber’s (c.o.a.) $2.50 $50 Chili’s/Macaroni Grill/On the $2.75 $25 Gerber’s (c.o.a.) $5.00 $100 Boarder Chuck E. -

Corporate Governance and Managerial Incompetence: Lessons from Kmart

Brigham Young University Law School BYU Law Digital Commons Faculty Scholarship 4-30-1996 Corporate Governance and Managerial Incompetence: Lessons from Kmart D. Gordon Smith Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Business Law, Public Responsibility, and Ethics Commons, and the Business Organizations Law Commons Recommended Citation D. Gordon Smith, Corporate Governance and Managerial Incompetence: Lessons from Kmart, 74 N.C. L. REV., 1037 (1996). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by BYU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of BYU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CORPORATE GOVERNANCE AND MANAGERIAL INCOMPETENCE: LESSONS FROM KMART D. GORDON SMIm Modern corporategovernance scholars often extol an activist role by institutional investors in directing corporate activity. Widely viewed as a solution to the "collective action" problems that inhibit such activism by individual investors, institutional investors are praised for adding value to corporationsthrough their participationin the decisionmaking process. The ouster of Joseph Antonini as Chief Executive Officer of Kmart Corporation in 1995 might be taken as a vindication of this view, because substantialevidence indicates that institutionalinvestors played a crucial role in influencing Kmart's board of directors to remove him. In this Article, Professor Gordon Smith challenges this potential reading of the events at Kmart. Professor Smith poses the fundamental question of whether institutionalinvestor activism designed to address perceived incompetence among corporate managers consistently adds value to corporations in which such activism is present. ProfessorSmith analyzes the effect of internal and external forces on managers, particularly on Antonini. -

Investor Presentation September 15, 2020

Investor Presentation September 15, 2020 Franchise Group Proprietary Information Forward-Looking Statements This presentation contains forward-looking statements within the meaning of the securities laws (including the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995). Forward-looking statements can be identified by the fact that they do not relate strictly to historical or current facts. They may include words or variations of words such as “expects,” “anticipates,” “intends,” “plans,” “believes,” “seeks,” “estimates,” “projects,” “forecasts,” “targets,” “would,” “will,” “view,” “opportunity,” “potential,” “should,” “could,” or “may” or other similar words or expressions that convey projected future events or outcomes. Forward-looking statements provide the Company’s or its management’s current expectations, predictions, opinions or judgments of future conditions, events or results. All statements that address operating performance, events or developments that the Company expects or anticipates will occur in the future are forward-looking statements. They may include estimates or projections of revenues, income, earnings per share, capital expenditures, dividends, liquidity, capital structure, synergies, EBITDA or other financial items, descriptions of the Company’s or management’s plans or objectives for future operations, products or services, or descriptions of assumptions underlying any of the above. Such forward-looking statements are based on various assumptions as of the time they are made, and are inherently subject to known and -

Apple Blossom Times

Town of Newfane Historical Society’s Apple Blossom Times Since 1975 Spring 2019 Inside This Issue Spring is in the Air which we hope you enjoy! President’s Letter From the desk of our President One last thing: if you appreciate our newsletters, Minute History It was a wonderful autumn for the society, as I encourage you to renew we created great new memories from our fall your annual membership. The catalog that changed fundraisers. We had good turnouts for the They also make great gifts the world Apple Harvest Festival, Candlelight Tours at for others! Please check your the Van Horn Mansion, and our Annual Carol newsletter address label for Members Update Sing. Thanks to all our society members and current member status. Save the Date volunteers who made these events successful; Members up for renewal have asterisks * at the your hard work was very appreciated! end of their name. Use the enclosed form, or Historical Fun Fact Unfortunately I do not have everyone’s order online at newfanehistoricalsociety.com. names who helped, and thus don’t want to Membership is a vital way to support our society, Van Horn Mansion Tours single certain people out while appearing to especially during these quieter months. neglect others. Please know your efforts made a Calendar big difference in keeping our historical society Enjoy the coming spring, and we look forward to alive and well! writing again in May. Minute History As our locations are closed for the winter, this edition of our newsletter has additional space Vicki Banks For a short time Olcott was a to allow for a more extensive historical article, President known port on water routes at a time when boating was among the fastest ways to travel. -

SEARS HOLDINGS CORPORATION (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

United States Securities and Exchange Commission Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K x Annual Report Pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 For the Fiscal Year Ended January 28, 2017 or o Transition Report Pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 Commission file number 000-51217, 001-36693 SEARS HOLDINGS CORPORATION (Exact Name of Registrant as Specified in Its Charter) Delaware 20-1920798 (State of Incorporation) (I.R.S. Employer Identification No.) 3333 Beverly Road, Hoffman Estates, Illinois 60179 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) Registrant’s Telephone Number, Including Area Code: (847) 286-2500 Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of each class Name of Each Exchange on Which Registered Common Shares, par value $0.01 per share The NASDAQ Stock Market Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes ¨ No x Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. Yes ¨ No x Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such response) and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. -

FORWARD THINKING New Insights Into How Sears Gains Strength by Better Understanding Customers

SEARS CANADA INC. SEARS CANADA INC. SEARS CANADA INC. 1997 Annual Report FORWARD THINKING New insights into how Sears gains strength by better understanding customers TRANSFORMING SEARS INSIDE OUT An inside look at Sears $300 million nationwide revitalization program CLOSER TO HOME Sears Whole Home Furniture Stores and dealer stores key to Sears innovative off-mall growth strategy 2 CHAIRMAN’S MESSAGE Paul Walters reflects on 21 FINANCIAL INFORMATION 1997 the gratifying results of 1997, and shares his perspective on Sears strategy for growth 22 Eleven Year Summary 6 FORWARD THINKING Sears reinvents the way it 23 Management’s Discussion and Analysis does business to become more relevant to customers 33 Quarterly Results and Common Share Market 8 BRAND NEW LIFE Creating a brand image for Information and Dividend Highlights Sears helps grow lifetime customer relationships 34 Statement of Management Responsibility 10 TRANSFORMING SEARS INSIDE OUT and Auditors’ Report Revitalization of 9 GTA stores first stage of $300 35 Consolidated Statements of Financial Position million capital investment program to totally transform Sears by the beginning of the new 36 Consolidated Statements of Earnings millennium 36 Consolidated Statements of Retained Earnings 14 THE MANY SIDES OF SEARS Customers see how Sears meets their many needs in new 37 Consolidated Statements of advertising campaign Changes in Financial Position 16 BEST SELLER Sears reveals why catalogue 38 Notes to Consolidated Financial Statements shopping has an exciting future CORPORATE INFORMATION 18 CLOSER TO HOME Off-mall strategy brings 46 Corporate Governance customers closer to Sears 47 Directors and Officers 20 COMMUNITY RELATIONSHIPS Communities benefit from Sears caring side 48 Corporate Information Sears is Canada’s largest single retailer of general merchandise, with department and specialty stores as well as catalogue locations across Canada. -

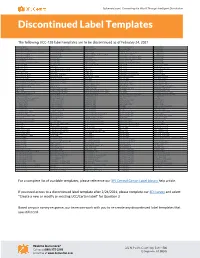

Discontinued Label Templates

3plcentral.com | Connecting the World Through Intelligent Distribution Discontinued Label Templates The following UCC-128 label templates are to be discontinued as of February 24, 2021. AC Moore 10913 Department of Defense 13318 Jet.com 14230 Office Max Retail 6912 Sears RIM 3016 Ace Hardware 1805 Department of Defense 13319 Joann Stores 13117 Officeworks 13521 Sears RIM 3017 Adorama Camera 14525 Designer Eyes 14126 Journeys 11812 Olly Shoes 4515 Sears RIM 3018 Advance Stores Company Incorporated 15231 Dick Smith 13624 Journeys 11813 New York and Company 13114 Sears RIM 3019 Amazon Europe 15225 Dick Smith 13625 Kids R Us 13518 Harris Teeter 13519 Olympia Sports 3305 Sears RIM 3020 Amazon Europe 15226 Disney Parks 2806 Kids R Us 6412 Orchard Brands All Divisions 13651 Sears RIM 3105 Amazon Warehouse 13648 Do It Best 1905 Kmart 5713 Orchard Brands All Divisions 13652 Sears RIM 3206 Anaconda 13626 Do It Best 1906 Kmart Australia 15627 Orchard Supply 1705 Sears RIM 3306 Associated Hygienic Products 12812 Dot Foods 15125 Lamps Plus 13650 Orchard Supply Hardware 13115 Sears RIM 3308 ATTMobility 10012 Dress Barn 13215 Leslies Poolmart 3205 Orgill 12214 Shoe Sensation 13316 ATTMobility 10212 DSW 12912 Lids 12612 Orgill 12215 ShopKo 9916 ATTMobility 10213 Eastern Mountain Sports 13219 Lids 12614 Orgill 12216 Shoppers Drug Mart 4912 Auto Zone 1703 Eastern Mountain Sports 13220 LL Bean 1702 Orgill 12217 Spencers 6513 B and H Photo 5812 eBags 9612 Loblaw 4511 Overwaitea Foods Group 6712 Spencers 7112 Backcountry.com 10712 ELLETT BROTHERS 13514 Loblaw -

Zak Kitnick Craftsman by Sears at Kmart Press Release

ribordy contemporary ZAK KITNICK: Craftsman by Sears at Kmart May 17 - July 6, 2018 1886: Richard Warren Sears starts a mail order watch business called R.W Sears Watch Company in Minneapolis Minnesota 1887: The R.W Sears Watch Company relocates to Chicago Illinois 1887: The R.W Sears Watch Company publishes their first mail order catalog offering watches, diamonds, and jewelry 1889: Sears sells his business for $100,000 ($2.7 million today) and relocates to Iowa 1892: Richard Sears returns to Chicago and establishes a new mail order with his partner, Alvah Curtis Roebuck, operating as the A.C. Roebuck Watch Company 1893: They rename the company to Sears, Roebuck and Company and begin to diversity the offerings in their catalog 1894: The Sears catalog grows to 322 pages, featuring sewing machines, bicycles, sporting goods, automobiles, and other items 1906: Sales continue to grow rapidly, and the prosperity of the company and their vision for greater expansion leads Sears to take the company public. Sears' 1906 initial public offering marks the first major retail IPO in American financial history 1925: Sears opens its first store in Chicago Illinois 1927: Arthur Barrows, head of the Sears hardware department buys the right to use the name Craftsman from the Marion-Craftsman Tool Company for $500 1927: Sears creates the Kenmore brand for appliances and the Craftsman brand for tools. 1927: The Craftsman trademark is registered by Sears on May 20, 1927 1927: The first Craftsman tools are sold 1930: At this time, Craftsman tools are a hodge-podge of styles and designs.