Countering Violent Extremism in Peshawar Pakistan Licona Bryan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pakistan-U.S. Relations

Order Code RL33498 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Pakistan-U.S. Relations Updated October 26, 2006 K. Alan Kronstadt Specialist in Asian Affairs Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress Pakistan-U.S. Relations Summary A stable, democratic, economically thriving Pakistan is considered vital to U.S. interests. U.S. concerns regarding Pakistan include regional terrorism; Pakistan- Afghanistan relations; weapons proliferation; the ongoing Kashmir problem and Pakistan-India tensions; human rights protection; and economic development. A U.S.-Pakistan relationship marked by periods of both cooperation and discord was transformed by the September 2001 terrorist attacks on the United States and the ensuing enlistment of Pakistan as a key ally in U.S.-led counterterrorism efforts. Top U.S. officials regularly praise Islamabad for its ongoing cooperation, although doubts exist about Islamabad’s commitment to some core U.S. interests. Pakistan is identified as a base for terrorist groups and their supporters operating in Kashmir, India, and Afghanistan. Since late 2003, Pakistan’s army has been conducting unprecedented counterterrorism operations in the country’s western tribal areas. Separatist violence in India’s Muslim-majority Jammu and Kashmir state has continued unabated since 1989, with some notable relative decline in recent years. India has blamed Pakistan for the infiltration of Islamic militants into Indian Kashmir, a charge Islamabad denies. The United States reportedly has received pledges from Islamabad that all “cross-border terrorism” would cease and that any terrorist facilities in Pakistani-controlled areas would be closed. Similar pledges have been made to India. -

Stephen Philip Cohen the Idea Of

00 1502-1 frontmatter 8/25/04 3:17 PM Page iii the idea of pakistan stephen philip cohen brookings institution press washington, d.c. 00 1502-1 frontmatter 8/25/04 3:17 PM Page v CONTENTS Preface vii Introduction 1 one The Idea of Pakistan 15 two The State of Pakistan 39 three The Army’s Pakistan 97 four Political Pakistan 131 five Islamic Pakistan 161 six Regionalism and Separatism 201 seven Demographic, Educational, and Economic Prospects 231 eight Pakistan’s Futures 267 nine American Options 301 Notes 329 Index 369 00 1502-1 frontmatter 8/25/04 3:17 PM Page vi vi Contents MAPS Pakistan in 2004 xii The Subcontinent on the Eve of Islam, and Early Arab Inroads, 700–975 14 The Ghurid and Mamluk Dynasties, 1170–1290 and the Delhi Sultanate under the Khaljis and Tughluqs, 1290–1390 17 The Mughal Empire, 1556–1707 19 Choudhary Ramat Ali’s 1940 Plan for Pakistan 27 Pakistan in 1947 40 Pakistan in 1972 76 Languages of Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Northwest India 209 Pakistan in Its Larger Regional Setting 300 01 1502-1 intro 8/25/04 3:18 PM Page 1 Introduction In recent years Pakistan has become a strategically impor- tant state, both criticized as a rogue power and praised as being on the front line in the ill-named war on terrorism. The final report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States iden- tifies Pakistan, along with Afghanistan and Saudi Arabia, as a high- priority state. This is not a new development. -

REFORM OR REPRESSION? Post-Coup Abuses in Pakistan

October 2000 Vol. 12, No. 6 (C) REFORM OR REPRESSION? Post-Coup Abuses in Pakistan I. SUMMARY............................................................................................................................................................2 II. RECOMMENDATIONS.......................................................................................................................................3 To the Government of Pakistan..............................................................................................................................3 To the International Community ............................................................................................................................5 III. BACKGROUND..................................................................................................................................................5 Musharraf‘s Stated Objectives ...............................................................................................................................6 IV. CONSOLIDATION OF MILITARY RULE .......................................................................................................8 Curbs on Judicial Independence.............................................................................................................................8 The Army‘s Role in Governance..........................................................................................................................10 Denial of Freedoms of Assembly and Association ..............................................................................................11 -

Volume VIII, Issue-3, March 2018

Volume VIII, Issue-3, March 2018 March in History Nation celebrates Pakistan Day 2018 with military parade, gun salutes March 15, 1955: The biggest contingents of armoured and mech - post-independence irrigation anised infantry held a march-past. project, Kotri Barrage is Pakistan Army tanks, including the inaugurated. Al Khalid and Al Zarrar, presented March 23 , 1956: 1956 Constitution gun salutes to the president. Radar is promulgates on Pakistan Day. systems and other weapons Major General Iskander Mirza equipped with military tech - sworn in as first President of nology were also rolled out. Pakistan. The NASR missile, the Sha - heen missile, the Ghauri mis - March 23, 1956: Constituent sile system, and the Babur assembly adopts name of Islamic cruise missile were also fea - Republic of Pakistan and first constitution. The nation is celebrating Pakistan A large number of diplomats from tured in the parade. Day 2018 across the country with several countries attended the March 8, 1957: President Various aeroplanes traditional zeal and fervour. ceremony. The guest of honour at Iskandar Mirza lays the belonging to Army Avi - foundation-stone of the State Bank the ceremony was Sri Lankan Pres - Pakistan Day commemorates the ation and Pakistan Air of Pakistan building in Karachi. ident Maithripala Sirisena. passing of the Lahore Resolution Force demonstrated aer - obatic feats for the March 23, 1960: Foundation of on March 23, 1940, when the All- Contingents of Pakistan Minar-i-Pakistan is laid. India Muslim League demanded a Army, Pakistan Air Force, and audience. Combat separate nation for the Muslims of Pakistan Navy held a march-past and attack helicopters, March 14, 1972: New education the British Indian Empire. -

Washington's Handprints Found in Pakistan Crisis Management

Click here for Full Issue of EIR Volume 20, Number 29, July 30, 1993 Washington's handprints found in Pakistan crisis management by Susan B. Maitra and Ramtanu Maitra The three-month crisis in Pakistan, which took a full-blown whom are retired Anny men, have also been named. fonn on April 18 with the President dissolving Parliament and sacking the prime minister, has gone into a temporary u.s. meddling lull, with both the President, Ghulam Ishaq Khan, and the Prior to and throughout the crisis, one major player re prime minister, Nawaz Sharif, agreeing to step down. A mained in the shadows, namely Washington. Prime Minister caretaker prime minister and a caretaker President have as Sharif got on the wrong side of Washington when Arab lead sumed control at the center and four provinces of Pakistan, ers, allies of the United States, began complaining early this and preparations for the Oct. 6 national assembly and the year about the training of Muslim guerrillas in Pakistan by Oct. 9 provincial assembly elections have begun. the Pakistani Inter-Services Intelligence, under the tutelage The crisis had turned into a sordid drama and the country of Javed Nasir, an orthodox Muslim and a close follower of was increasingly ungovernable.During this period, the duly the prime minister. elected Nawaz Sharif governmentand the National Assembly Although Nawaz Sharif had supported the U.S. role in were dissolved by the President, who was already engaged the Gulf war and bent over backwards to accommodate the in a bitter feud with the prime minister. -

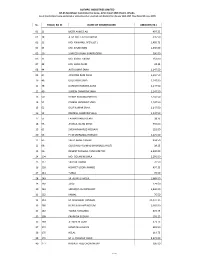

Sl. Folio/ Bo Id Name of Shareholder Amount (Tk.) 01 11

OLYMPIC INDUSTRIES LIMITED 62-63 Motijheel Commmercial Area, Amin Court (6th Floor), Dhaka. List of shareholders having unclaimed or undistributed or unsettled cash dividend for the year 2016-2017 (Year Ended 30 June, 2017) SL. FOLIO/ BO ID NAME OF SHAREHOLDER AMOUNT (TK.) 01 11 MEER AHMED ALI 497.25 02 18 A. M. MD. FAZLUR RAHIM 535.50 03 23 MD. ANWARUL AFZAL (JT.) 2,409.75 04 24 MD. AYUB KHAN 1,530.00 05 26 SHAHED HASAN SHARFUDDIN 306.00 06 31 MD. ABDUL HAKIM 153.00 07 38 MD. SHAH ALAM 38.25 08 44 AJIT KUMAR SAHA 1,147.50 09 45 JOSHODA RANI SAHA 1,147.50 10 46 DULU RANI SAHA 1,147.50 11 48 NARESH CHANDRA SAHA 1,147.50 12 49 SURESH CHANDRA SAHA 1,147.50 13 50 BENOY KRISHNA PODDER 1,147.50 14 51 PARESH CHANDRA SAHA 1,147.50 15 52 DILIP KUMAR SAHA 1,147.50 16 53 RAMESH CHANDRA SAHA 1,147.50 17 55 FARHAD BANU ISLAM 38.25 18 56 AMINUL ISLAM KHAN 765.00 19 61 SHEIKH MAHFUZ HOSSAIN 153.00 20 63 F I M MOFAZZAL HOSSAIN 5,125.50 21 65 SAJED AHMED KHAN 994.50 22 68 QUAZI MUHAMMAD SHAHIDULLAH (JT) 38.25 23 96 REGENT MOGHUL FUND LIMITED 6,300.00 24 104 MD. GOLAM MOWLA 2,295.00 25 117 SABERA ZAMAN 76.50 26 126 HEMYET UDDIN AHMED 497.25 27 141 TUBLA 76.50 28 149 SK. ALIMUL HAQUE 1,989.00 29 160 JALAL 229.50 30 161 SIDDIQUA CHOWDHURY 1,530.00 31 162 KAMAL 76.50 32 163 M. -

Report on Judicial Reforms

REPORT OF THE COMMITTEE ON JUDICIAL REFORMS LAW, PARLIAMENTARY AFFAIRS & HUMAN RIGHTS DEPARTMENT GOVERNMENT OF THE PUNJAB . CONTENTS Sr. No. Contents Page 1. Preface 2. Contents 3. Executive Summary 4. Introduction 5. Legal Education 6. Improving Legal Education Standard 7. Recruitment/Promotion of Judicial Officers 8. Training of Judicial Officer 9. Continued Legal Education Provincial Judicial Academy 10. Alternate Dispute Resolution Process 11. Administrative Measures 12. Investigation 13. Disposal of Backlog 14. Coordination between Bench & Bar 15. Law Commission 16. Recommendations at a glance. ANNEXURES Annex ‘A’ Regulations providing for pre-service & in-service training of judicial officers. Annex ‘B’ Provincial Judicial Academy Act 2007. Annex ‘C’ Proposed amendments in the Provincial Judicial Academy Act. Annex ‘D’ Proposed draft of Order XA to be added in CPC. Annex ‘E’ Draft instructions on Standard of Conduct of Arbitrators/Mediators” proposal to the High court Annex ‘F’ “Allocation Questionnaire Form” Proposed specimen to be filed in newly constituted suits/cases/or cases pending before coming into force of Order X.A Annex ‘G’ “Allocation Questionnaire Form” (To be filled in Family Matters) Annex ‘H’ “Allocation Questionnaire Form” (To be filed in Appeals). Annex ‘J’ Letter requesting High Court to ensure compliance of its instruction regarding expeditious disposal etc. 2 PREFACE The electorate in Pakistan has returned those political parties and political personalities to the corridors of power, who spoke of independence of judiciary and of strengthening the administration of justice so as to provide justice and relief to the citizens. Only vibrant and effective justice system can ensure enjoyment of fundamental rights by the common man. -

Litigation & Dispute Resolution

Litigation & Dispute Resolution Second Edition Contributing Editor: Michael Madden Published by Global Legal Group CONTENTS Preface Michael Madden, Winston & Strawn London Austria Christian Eder, Christoph Hauser & Alexandra Wolff, Fiebinger Polak Leon Attorneys-at-Law 1 Belgium Koen Van den Broeck & Thales Mertens, Allen & Overy LLP 9 British Virgin Islands Scott Cruickshank & David Harby, Lennox Paton 14 Bulgaria Assen Georgiev, CMS Cameron McKenna LLP – Bulgaria Branch 25 Canada Caroline Abela, Krista Chaytor & Marie-Andrée Vermette, WeirFoulds LLP 35 Cayman Islands Ian Huskisson, Anna Peccarino & Charmaine Richter, Travers Thorp Alberga 44 Cyprus Anastasios A. Antoniou & Louiza Petrou, Anastasios Antoniou LLC 51 England & Wales Michael Madden & Justin McClelland, Winston & Strawn London 59 Estonia Pirkka-Marja Põldvere & Marko Pikani, Aivar Pilv Law Offi ce 75 Finland Markus Kokko & Niki J. Welling, Attorneys at Law Borenius Ltd 86 France Philippe Cavalieros, Winston & Strawn LLP, Paris 92 Germany Dr. Stefan Rützel & Dr. Andrea Leufgen, Gleiss Lutz 99 Guernsey Christian Hay & Michael Adkins, Collas Crill 107 India Siddharth Thacker, Mulla & Mulla & Craigie Blunt & Caroe 114 Indonesia Alexandra Gerungan, Lia Alizia & Christian F. Sinatra, Makarim & Taira S. 123 Ireland Seán Barton & Heather Mahon, McCann FitzGerald 131 Isle of Man Charles Coleman & Chris Webb, Gough Law 142 Italy Ferdinando Emanuele & Milo Molfa, Cleary Gottlieb Steen & Hamilton LLP 149 Jersey Kathryn Purkis & Dan Boxall, Collas Crill 158 Korea Kap-you (Kevin) Kim, John P. Bang & David MacArthur, Bae, Kim & Lee LLC 167 Malaysia Claudia Cheah Pek Yee & Leong Wai Hong, Skrine 176 Mexico Miguel Angel Hernandez-Romo Valencia & Miguel Angel Hernandez-Romo, Bufete Hernández Romo 186 Nigeria Matthias Dawodu, Olaoye Olalere & Debo Ogunmuyiwa, S. -

Pakistan's Violence

Pakistan’s Violence Causes of Pakistan’s increasing violence since 2001 Anneloes Hansen July 2015 Master thesis Political Science: International Relations Word count: 21481 First reader: S. Rezaeiejan Second reader: P. Van Rooden Studentnumber: 10097953 1 Table of Contents List of Abbreviations and Acronyms List of figures, Maps and Tables Map of Pakistan Chapter 1. Introduction §1. The Case of Pakistan §2. Research Question §3. Relevance of the Research Chapter 2. Theoretical Framework §1. Causes of Violence §1.1. Rational Choice §1.2. Symbolic Action Theory §1.3. Terrorism §2. Regional Security Complex Theory §3. Colonization and the Rise of Institutions §4. Conclusion Chapter 3. Methodology §1. Variables §2. Operationalization §3. Data §4. Structure of the Thesis Chapter 4. Pakistan §1. Establishment of Pakistan §2. Creating a Nation State §3. Pakistan’s Political System §4. Ethnicity and Religion in Pakistan §5. Conflict and Violence in Pakistan 2 §5.1. History of Violence §5.2. Current Violence §5.2.1. Baluchistan §5.2.2. Muslim Extremism and Violence §5. Conclusion Chapter 5. Rational Choice in the Current Conflict §1. Weak State §2. Economy §3. Instability in the Political Centre §4. Alliances between Centre and Periphery §5. Conclusion Chapter 6. Emotions in Pakistan’s Conflict §1. Discrimination §2. Hatred towards Others §2.1. Political Parties §2.2 Extremist Organizations §3. Security Dilemma §4. Conclusion Chapter 7. International Influences §1. International Relations §1.1. United States – Pakistan Relations §1.2. China – -

Earlier Research Work on Tharparkar and Sindh Barrage, and Similar Studies Related to Demographic, Social and Economic Conditions

Munich Personal RePEc Archive Earlier Research Work on Tharparkar and Sindh Barrage, and Similar Studies Related to Demographic, Social and Economic Conditions Herani, Gobind M. University of Sindh 5 April 2002 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/15950/ MPRA Paper No. 15950, posted 30 Jun 2009 00:20 UTC Earlier Research Work on Tharparkar and Sindh Barrage, and Similar Studies Related to Demographic, Social and Economic Conditions 51 EARLIER RESEARCH WORK ON THARPARKAR AND SINDH BARRAGE, AND SIMILAR STUDIES RELATED TO DEMOGRAPHIC, SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC CONDITIONS Gobind M. Herani Khadam Ali Shah Bukhari Institute of Technology Abstract This study is earlier research works done on Tharparkar and Sindh barrage, and similar studies related to demographic, social and economic conditions and chapter-2 as a literature review of the thesis of Ph.D submitted in 2002. Purpose of the chapter was to give the complete picture of both areas and at national and international level to support the primary data of the thesis for proper occlusions and recommendations for policy maker to get the lesson for Tharparkar to get prosperous and better demographically socially and economically. Only secondary data from reliable sources is given in this chapter with complete quotations. This study shows that earlier research work is done in Thar with the help of Government of Sindh, United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) Save the Children Fund (SCF)-U.K , titled as ” Tharparkar rural Development Project (TRDP) Evaluation 1993”. From, the detailed study of the chapter we conclude that, from Pakistan origin material, we expect more in future. -

Who Is Who in Pakistan & Who Is Who in the World Study Material

1 Who is Who in Pakistan Lists of Government Officials (former & current) Governor Generals of Pakistan: Sr. # Name Assumed Office Left Office 1 Muhammad Ali Jinnah 15 August 1947 11 September 1948 (died in office) 2 Sir Khawaja Nazimuddin September 1948 October 1951 3 Sir Ghulam Muhammad October 1951 August 1955 4 Iskander Mirza August 1955 (Acting) March 1956 October 1955 (full-time) First Cabinet of Pakistan: Pakistan came into being on August 14, 1947. Its first Governor General was Muhammad Ali Jinnah and First Prime Minister was Liaqat Ali Khan. Following is the list of the first cabinet of Pakistan. Sr. Name of Minister Ministry 1. Liaqat Ali Khan Prime Minister, Foreign Minister, Defence Minister, Minister for Commonwealth relations 2. Malik Ghulam Muhammad Finance Minister 3. Ibrahim Ismail Chundrigar Minister of trade , Industries & Construction 4. *Raja Ghuzanfar Ali Minister for Food, Agriculture, and Health 5. Sardar Abdul Rab Nishtar Transport, Communication Minister 6. Fazal-ul-Rehman Minister Interior, Education, and Information 7. Jogendra Nath Mandal Minister for Law & Labour *Raja Ghuzanfar’s portfolio was changed to Minister of Evacuee and Refugee Rehabilitation and the ministry for food and agriculture was given to Abdul Satar Pirzada • The first Chief Minister of Punjab was Nawab Iftikhar. • The first Chief Minister of NWFP was Abdul Qayum Khan. • The First Chief Minister of Sindh was Muhamad Ayub Khuro. • The First Chief Minister of Balochistan was Ataullah Mengal (1 May 1972), Balochistan acquired the status of the province in 1970. List of Former Prime Ministers of Pakistan 1. Liaquat Ali Khan (1896 – 1951) In Office: 14 August 1947 – 16 October 1951 2. -

3 Who Is Who and What Is What

3 e who is who and what is what Ever Success - General Knowledge 4 Saad Book Bank, Lahore Ever Success Revised and Updated GENERAL KNOWLEDGE Who is who? What is what? CSS, PCS, PMS, FPSC, ISSB Police, Banks, Wapda, Entry Tests and for all Competitive Exames and Interviews World Pakistan Science English Computer Geography Islamic Studies Subjectives + Objectives etc. Abbreviations Current Affair Sports + Games Ever Success - General Knowledge 5 Saad Book Bank, Lahore © ALL RIGHTS RESERVED No part of this book may be reproduced In any form, by photostate, electronic or mechanical, or any other means without the written permission of author and publisher. Composed By Muhammad Tahsin Ever Success - General Knowledge 6 Saad Book Bank, Lahore Dedicated To ME Ever Success - General Knowledge 7 Saad Book Bank, Lahore Ever Success - General Knowledge 8 Saad Book Bank, Lahore P R E F A C E I offer my services for designing this strategy of success. The material is evidence of my claim, which I had collected from various resources. I have written this book with an aim in my mind. I am sure this book will prove to be an invaluable asset for learners. I have tried my best to include all those topics which are important for all competitive exams and interviews. No book can be claimed as prefect except Holy Quran. So if you found any shortcoming or mistake, you should inform me, according to your suggestions, improvements will be made in next edition. The author would like to thank all readers and who gave me their valuable suggestions for the completion of this book.