Pakistan Elects a New President

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

REFORM OR REPRESSION? Post-Coup Abuses in Pakistan

October 2000 Vol. 12, No. 6 (C) REFORM OR REPRESSION? Post-Coup Abuses in Pakistan I. SUMMARY............................................................................................................................................................2 II. RECOMMENDATIONS.......................................................................................................................................3 To the Government of Pakistan..............................................................................................................................3 To the International Community ............................................................................................................................5 III. BACKGROUND..................................................................................................................................................5 Musharraf‘s Stated Objectives ...............................................................................................................................6 IV. CONSOLIDATION OF MILITARY RULE .......................................................................................................8 Curbs on Judicial Independence.............................................................................................................................8 The Army‘s Role in Governance..........................................................................................................................10 Denial of Freedoms of Assembly and Association ..............................................................................................11 -

Pakistan Was Suspended by President General Musharaff in March Last Year Leading to a Worldwide Uproar Against This Act

A Coup against Judicial Independence . Special issue of the CJEI Report (February, 2008) ustice Iftikhar Muhammad Chaudhry, the twentieth Chief Justice of Pakistan was suspended by President General Musharaff in March last year leading to a worldwide uproar against this act. However, by a landmark order J handed down by the Supreme Court of Pakistan, Justice Chaudhry was reinstated. We at the CJEI were delighted and hoped that this would put an end to the ugly confrontation between the judiciary and the executive. However our happiness was short lived. On November 3, 2007, President General Musharaff suspended the constitution and declared a state of emergency. Soon the Pakistan army entered the Supreme Court premises removing Justice Chaudhry and other judges. The Constitution was also suspended and was replaced with a “Provisional Constitutional Order” enabling the Executive to sack Chief Justice Chaudhry, and other judges who refused to swear allegiance to this extraconstitutional order. Ever since then, the judiciary in Pakistan has been plunged into turmoil and Justice Chaudhry along with dozens of other Justices has been held incommunicado in their homes. Any onslaught on judicial independence is a matter of grave concern to all more so to the legal and judicial fraternity in countries that are wedded to the rule of law. In the absence of an independent judiciary, human rights and constitutional guarantees become meaningless; the situation capable of jeopardising even the long term developmental goals of a country. As observed by Viscount Bryce, “If the lamp of justice goes out in darkness, how great is the darkness.” This is really true of Pakistan which is presently going through testing times. -

Makers-Of-Modern-Sindh-Feb-2020

Sindh Madressah’s Roll of Honor MAKERS OF MODERN SINDH Lives of 25 Luminaries Sindh Madressah’s Roll of Honor MAKERS OF MODERN SINDH Lives of 25 Luminaries Dr. Muhammad Ali Shaikh SMIU Press Karachi Alma-Mater of Quaid-e-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah Sindh Madressatul Islam University, Karachi Aiwan-e-Tijarat Road, Karachi-74000 Pakistan. This book under title Sindh Madressah’s Roll of Honour MAKERS OF MODERN SINDH Lives of 25 Luminaries Written by Professor Dr. Muhammad Ali Shaikh 1st Edition, Published under title Luminaries of the Land in November 1999 Present expanded edition, Published in March 2020 By Sindh Madressatul Islam University Price Rs. 1000/- SMIU Press Karachi Copyright with the author Published by SMIU Press, Karachi Aiwan-e-Tijarat Road, Karachi-74000, Pakistan All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any from or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passage in a review Dedicated to loving memory of my parents Preface ‘It is said that Sindh produces two things – men and sands – great men and sandy deserts.’ These words were voiced at the floor of the Bombay’s Legislative Council in March 1936 by Sir Rafiuddin Ahmed, while bidding farewell to his colleagues from Sindh, who had won autonomy for their province and were to go back there. The four names of great men from Sindh that he gave, included three former students of Sindh Madressah. Today, in 21st century, it gives pleasure that Sindh Madressah has kept alive that tradition of producing great men to serve the humanity. -

Honour Killing in Sindh Men's and Women's Divergent Accounts

Honour Killing in Sindh Men's and Women's Divergent Accounts Shahnaz Begum Laghari PhD University of York Women’s Studies March 2016 Abstract The aim of this project is to investigate the phenomenon of honour-related violence, the most extreme form of which is honour killing. The research was conducted in Sindh (one of the four provinces of Pakistan). The main research question is, ‘Are these killings for honour?’ This study was inspired by a need to investigate whether the practice of honour killing in Sindh is still guided by the norm of honour or whether other elements have come to the fore. It is comprised of the experiences of those involved in honour killings through informal, semi- structured, open-ended, in-depth interviews, conducted under the framework of the qualitative method. The aim of my thesis is to apply a feminist perspective in interpreting the data to explore the tradition of honour killing and to let the versions of the affected people be heard. In my research, the women who are accused as karis, having very little redress, are uncertain about their lives; they speak and reveal the motives behind the allegations and killings in the name of honour. The male killers, whom I met inside and outside the jails, justify their act of killing in the name of honour, culture, tradition and religion. Drawing upon interviews with thirteen women and thirteen men, I explore and interpret the data to reveal their childhood, educational, financial and social conditions and the impacts of these on their lives, thoughts and actions. -

View of Above, It Is Observed That Instant Petition (C.P

IN THE HIGH COURT OF SINDH, CIRCUIT COURT, HYDERABAD Present: Mr. Justice Abdul Maalik Gaddi Mr. Justice Khadim Hussain Tunio 1. C.P No.D- 3183 of 2018 Dr. Fateh Muhammad Burfat --------- Petitioner Versus Province of Sindh and others --------- Respondents 2. C.P No.D- 3206 of 2018 Prof. Dr. Muneeruddin --------- Petitioner Versus Province of Sindh and others --------- Respondents 3. C.P No.D- 1874 of 2019 Dr. Arfana Mallah --------- Petitioner Versus Federation of Pakistan and others --------- Respondents 4. CP No.D- 2380 of 2019 Dr. Fateh Muhammad Burfat -------- Petitioner Versus Province of Sindh and others -------- Respondents 2 Date of Hearings : 6.02.2020, 03.03.2020 & 10.03.2020 Date of order : 10.03.2020 Mr. Rafique Ahmed Kalwar Advocate for Petitioner in C.P. Nos.D- 3183 of 2018, 2380 of 2019 and for Respondent No.5 in C.P. No.D- 1874 of 2019. Mr. Shabeer Hussain Memon, Advocate for Petitioner in C.P. No.D- 3206 of 2018. Mr. K.B. Lutuf Ali Laghari Advocate for Petitioner in C.P. No.D- 1874 of 2019 and intervener in C.P. No.D- 2380 of 2019. Mr. Allah Bachayo Soomro, Additional Advocate General, Sindh alongwith Jawad Karim AD (Legal) ACE Jamshoro on behalf of ACE Sindh. Mr. Kamaluddin Advocate also appearing for Respondent No.5 in C.P. No.D- 1874 of 2019. None present for respondent No.1 (Federation of Pakistan) in C.P. No.D-1874/2019. O R D E R ABDUL MAALIK GADDI, J.- By this common order, we intend to dispose of aforementioned four constitutional petitions together as a common question of facts and law is involved in all these petitions as well as the subject matter is also interconnected. -

Pakistan's Violence

Pakistan’s Violence Causes of Pakistan’s increasing violence since 2001 Anneloes Hansen July 2015 Master thesis Political Science: International Relations Word count: 21481 First reader: S. Rezaeiejan Second reader: P. Van Rooden Studentnumber: 10097953 1 Table of Contents List of Abbreviations and Acronyms List of figures, Maps and Tables Map of Pakistan Chapter 1. Introduction §1. The Case of Pakistan §2. Research Question §3. Relevance of the Research Chapter 2. Theoretical Framework §1. Causes of Violence §1.1. Rational Choice §1.2. Symbolic Action Theory §1.3. Terrorism §2. Regional Security Complex Theory §3. Colonization and the Rise of Institutions §4. Conclusion Chapter 3. Methodology §1. Variables §2. Operationalization §3. Data §4. Structure of the Thesis Chapter 4. Pakistan §1. Establishment of Pakistan §2. Creating a Nation State §3. Pakistan’s Political System §4. Ethnicity and Religion in Pakistan §5. Conflict and Violence in Pakistan 2 §5.1. History of Violence §5.2. Current Violence §5.2.1. Baluchistan §5.2.2. Muslim Extremism and Violence §5. Conclusion Chapter 5. Rational Choice in the Current Conflict §1. Weak State §2. Economy §3. Instability in the Political Centre §4. Alliances between Centre and Periphery §5. Conclusion Chapter 6. Emotions in Pakistan’s Conflict §1. Discrimination §2. Hatred towards Others §2.1. Political Parties §2.2 Extremist Organizations §3. Security Dilemma §4. Conclusion Chapter 7. International Influences §1. International Relations §1.1. United States – Pakistan Relations §1.2. China – -

Politics of Sindh Under Zia Government an Analysis of Nationalists Vs Federalists Orientations

POLITICS OF SINDH UNDER ZIA GOVERNMENT AN ANALYSIS OF NATIONALISTS VS FEDERALISTS ORIENTATIONS A Thesis Doctor of Philosophy By Amir Ali Chandio 2009 Department of Political Science & International Relations Bahauddin Zakariya University Multan POLITICS OF SINDH UNDER ZIA GOVERNMENT AN ANALYSIS OF NATIONALISTS VS FEDERALISTS ORIENTATIONS A Thesis Doctor of Philosophy By Amir Ali Chandio 2009 Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Ishtiaq Ahmed Chaudhry Department of Political Science & International Relations Bahauddin Zakariya University Multan Dedicated to: Baba Bullay Shah & Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai The poets of love, fraternity, and peace DECLARATION This thesis is the result of my own investigations, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by giving explicit references. A bibliography is appended. This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed………………………………………………………………….( candidate) Date……………………………………………………………………. CERTIFICATES This is to certify that I have gone through the thesis submitted by Mr. Amir Ali Chandio thoroughly and found the whole work original and acceptable for the award of the degree of Doctorate in Political Science. To the best of my knowledge this work has not been submitted anywhere before for any degree. Supervisor Professor Dr. Ishtiaq Ahmed Choudhry Department of Political Science & International Relations Bahauddin Zakariya University, Multan, Pakistan Chairman Department of Political Science & International Relations Bahauddin Zakariya University, Multan, Pakistan. ABSTRACT The nationalist feelings in Sindh existed long before the independence, during British rule. The Hur movement and movement of the separation of Sindh from Bombay Presidency for the restoration of separate provincial status were the evidence’s of Sindhi nationalist thinking. -

Who Is Who in Pakistan & Who Is Who in the World Study Material

1 Who is Who in Pakistan Lists of Government Officials (former & current) Governor Generals of Pakistan: Sr. # Name Assumed Office Left Office 1 Muhammad Ali Jinnah 15 August 1947 11 September 1948 (died in office) 2 Sir Khawaja Nazimuddin September 1948 October 1951 3 Sir Ghulam Muhammad October 1951 August 1955 4 Iskander Mirza August 1955 (Acting) March 1956 October 1955 (full-time) First Cabinet of Pakistan: Pakistan came into being on August 14, 1947. Its first Governor General was Muhammad Ali Jinnah and First Prime Minister was Liaqat Ali Khan. Following is the list of the first cabinet of Pakistan. Sr. Name of Minister Ministry 1. Liaqat Ali Khan Prime Minister, Foreign Minister, Defence Minister, Minister for Commonwealth relations 2. Malik Ghulam Muhammad Finance Minister 3. Ibrahim Ismail Chundrigar Minister of trade , Industries & Construction 4. *Raja Ghuzanfar Ali Minister for Food, Agriculture, and Health 5. Sardar Abdul Rab Nishtar Transport, Communication Minister 6. Fazal-ul-Rehman Minister Interior, Education, and Information 7. Jogendra Nath Mandal Minister for Law & Labour *Raja Ghuzanfar’s portfolio was changed to Minister of Evacuee and Refugee Rehabilitation and the ministry for food and agriculture was given to Abdul Satar Pirzada • The first Chief Minister of Punjab was Nawab Iftikhar. • The first Chief Minister of NWFP was Abdul Qayum Khan. • The First Chief Minister of Sindh was Muhamad Ayub Khuro. • The First Chief Minister of Balochistan was Ataullah Mengal (1 May 1972), Balochistan acquired the status of the province in 1970. List of Former Prime Ministers of Pakistan 1. Liaquat Ali Khan (1896 – 1951) In Office: 14 August 1947 – 16 October 1951 2. -

Sent a Letter to the Government of Pakistan

TO: Mr. Muhammad Nawaz Sharif, Prime Minister of Pakistan Board CC: Cathy Albisa Mr. Mamnoon Hussain, President of Pakistan National Economic and Mr. Iqbal Ahmed Kalhoro, Acting Prosecutor General, Sindh Province Social Rights Initiative, USA Mr. Muhammad Arshad, Director General of Human Rights Mr. Chaudhry Nisar Ali Khan, Federal Minister for Interior and Narcotics Control Ruth Aura Odhiambo Federation of Women Mr. Pervaiz Rashid, Minister for Law, Justice and Human Rights Lawyers, Kenya Mr. Salman Aslam Butt, Attorney General Saeed Baloch Ms. Nadia Gabol, Minister for Human Rights, Sindh Province Pakistan Fisherfolk Forum, Mr. Michel Forst, UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights Defenders Pakistan UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention Hasan Barghouthi Democracy and Workers' Rights Center, Palestine RE: Concern about detention of human rights defender, Saeed Baloch Herman Kumara National Fisheries Solidarity Movement, Sri Lanka 21 January, 2016 Sandra Ratjen International Commission of Jurists, Switzerland Francisco Rocael Your Excellency, Consejo de Pueblos Wuxhtaj, Guatemala The International Network for Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ESCR-Net) is the largest global network of organizations and activists devoted to achieving economic, social and environmental justice through human rights, consisting of over 270 organizational and individual members in 70 countries. We write to express our deep concern regarding the recent arrest of Saeed Baloch, a Board member of ESCR-Net and General Secretary of the Pakistan Fisherfolk Forum (PFF), an organizational member of the Network. According to reports received, Mr. Baloch was arrested on Saturday, January 16, Chris Grove 2016, and taken into custody by the paramilitary security force Rangers. He was Director allegedly accused of financially assisting an individual involved in organized crime 370 Lexington Avenue and of embezzling fisheries’ funds. -

Pakistan 2013 Human Rights Report

PAKISTAN 2013 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Pakistan is a federal republic. There was significant consolidation of the country’s democratic institutions during the year. On May 11, the Pakistan Muslim League- Nawaz (PML-N) party won a majority of seats in parliamentary elections, and Nawaz Sharif became prime minister for the third time. The election marked the first time since independence in 1947 that one elected government completed its term and peacefully transferred power to another. Independent observers and some political parties, however, raised concerns about election irregularities. On September 8, President Asif Ali Zardari completed his five-year term and stepped down from office. His successor, President Mamnoon Hussain of the PML-N, took office the next day. Orderly transitions in both the military and the judiciary, in the positions of army chief of staff and Supreme Court chief justice, further solidified the democratic transition. The PML-N controlled the executive office, the National Assembly, and the Provincial Assembly of Punjab, with rival parties or coalitions governing the country’s three other provinces. The military and intelligence services nominally reported to civilian authorities but at times operated without effective civilian oversight, although the new government took steps to improve coordination with the military. Police generally reported to civilian authority, although there were instances in which police forces acted independently. Security forces sometimes committed abuses. The most serious human rights problems were extrajudicial and targeted killings, sectarian violence, disappearances, and torture. Other human rights problems included poor prison conditions, arbitrary detention, lengthy pretrial detention, a weak criminal justice system, lack of judicial independence in the lower courts, and infringement on citizens’ privacy rights. -

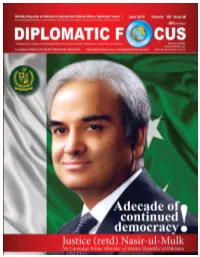

June 2018 Volume 09 Issue 06 “Publishing from Pakistan, United Kingdom/EU & Will Be Soon from UAE ”

June 2018 Volume 09 Issue 06 “Publishing from Pakistan, United Kingdom/EU & will be soon from UAE ” 09 10 19 31 09 Close and fraternal relations between Turkey is playing a very positive role towards the resolution Pakistan & Turkey are the guarantee of of different international issues. Turkey has dealt with the stability and prosperity in the region: Middle East crisis and especially the issue of refugees in a very positive manner, President Mamnoon Hussain 10 7th Caretaker PM of Pakistan Former Former CJP Nasirul Mulk was born on August 17, 1950 in CJP Nasirul Mulk Mingora, Swat. He completed his degree of Bar-at-Law from Inner Temple London and was called to the Bar in 1977. 19 President Emomali Rahmon expressed The sides discussed the issues of strengthening bilateral satisfaction over the friendly relations and cooperation in combating terrorism, extremism, drug multifaceted cooperation between production and transnational crime. Tajikistan & Pakistan 31 Colorful Cultural Exchanges between China and Pakistan are not only friendly neighbors, but also China and Pakistan two major ancient civilizations that have maintained close ties in cultural exchanges and mutual learning. The Royal wedding 2018 Since announcing their engagement in 13 November 2017, the world has been preparing for Prince Harry and Meghan Markle’s royal wedding. The Duke and Duchess of Sussex begin their first day as a married couple following an emotional ceremony that captivated the nation and a night spent partying with close family and friends. 06 Diplomatic Focus June 2018 RBI Mediaminds Contents Group of Publications Electronic & Print Media Production House 09 Pakistan & Turkey Close and fraternal relations …: President Mamnoon Hussain 10 7th Caretaker PM of Pakistan Former CJP Nasirul Mulk 12 The Royal wedding2018 Group Chairman/CEO: Mian Fazal Elahi 14 Pakistan & Saudi Arabia are linked through deep historic, religious and cultural Chief Editor: Mian Akhtar Hussain relations Patron in Chief: Mr. -

2. Lt. Col (R) Ayub Khan Is Appointed As Minster of Counter Terrorism Punjab

1. General (retired) Raheel Sharif appointed as a chief of Saudi-led Islamic anti-terror alliance of 39th Muslim nations. 2. Lt. Col (R) Ayub Khan is appointed as minster of counter terrorism punjab. 3. Om Puri, Indian actor died on 6th january 2017. 4. Pakistan has successfully Test-Fires Submarine launched Babur-3 Missile in January 2017 with range of 450 km. 5. Utad Bade Fateh Ali Khan pakistani classical & Khyal Singer belongs to patiala family died in Islamabad on 4th January 2017. 6. Blakh sher badini, notorious commander and handler of social media of Baluchistan Liberation Army (BLA) surrender in January 2017. 7. Justice (retired), Saeeduzzaman siddiqui, 31st Governor of Sindh died on 11 January 2017. 8. PM Nawaz Sharif attended World Economic Forum Annual Meeting held between 17-20 January 2017 in Davos, Switzerland. 9. Balraj Manra, famous urdu Novelist of India died on 16TH January 2017. 10. Turkish Cargo Jet has crashed near Krgystan's manas airport on its way from Hong Kong to Istanbul, Airline ACT Airlines 11. Sharmeen Obaid Chinoy was Co chairing the 47th world economic forum Annual Meeting. She was the first pakistani to Co chair the Meeting. 12. China has handed Over 2 Navy Ships to Pakistan for Gwadar Security named after two rivers Hingol and Basol.Two more ships will be soon handed over named after Baluchistan Two districts DASHT and ZHOB. 13. The privatization Commission's board agreed Tuesday to a proposal to lease out Pakistan steel Mills (PSM) recommending that the length of the lease agreement be 30 years.