Language, Identity and the State in Pakistan, 1947-48

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mrs. Maryam Faruqi

HAPPY HOME SCHOOL SYSTEM MRS. MARYAM FARUQI Tribute to a Pioneer in Education Mrs. Maryam Faruqi is a well-known name in the educational circles of Pakistan. She is the founder of the Happy Home School System. FAMILY HISTORY: Her success can be attributed to her passion for education and the restless desire to utilize her potential for the service of humanity. She was born in India to Sir Ebrahim and Lady Hawabai Ebrahim Haroon Jaffer. Her father tried to create an educational awakening amongst the Muslims and laid the foundation of the Bombay Provincial Muslim Educational Conference which was affiliated to the All India Mohammedan Educational Conference of Aligarh. He also set up a school in Pune which is to date offering excellent education to Muslim girls. EARLY EDUCATION: Her education started from the Islamia School, Pune, which is now a full-fledged school named after her parents. When she topped in grade- 6, she was asked by the Headmistress to teach Urdu to class-V. She felt on top of the world when at the end of the period the Headmistress remarked, “I bet you will be a good Headmistress.” That was her first success. She gave her Matriculation Examination through the Convent of Jesus and Mary, Pune and acquired First Merit Position. Her name remains etched on the Honour Roll Board. She joined the prestigious Naurosji Wadia College and her outstanding intermediate results earned her the Moosa Qasim Gold Medal. In 1945, she graduated from Bombay University with distinction & was awarded a Gold Medal in B.A Honours. -

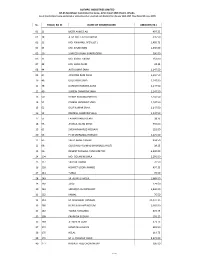

Sl. Folio/ Bo Id Name of Shareholder Amount (Tk.) 01 11

OLYMPIC INDUSTRIES LIMITED 62-63 Motijheel Commmercial Area, Amin Court (6th Floor), Dhaka. List of shareholders having unclaimed or undistributed or unsettled cash dividend for the year 2016-2017 (Year Ended 30 June, 2017) SL. FOLIO/ BO ID NAME OF SHAREHOLDER AMOUNT (TK.) 01 11 MEER AHMED ALI 497.25 02 18 A. M. MD. FAZLUR RAHIM 535.50 03 23 MD. ANWARUL AFZAL (JT.) 2,409.75 04 24 MD. AYUB KHAN 1,530.00 05 26 SHAHED HASAN SHARFUDDIN 306.00 06 31 MD. ABDUL HAKIM 153.00 07 38 MD. SHAH ALAM 38.25 08 44 AJIT KUMAR SAHA 1,147.50 09 45 JOSHODA RANI SAHA 1,147.50 10 46 DULU RANI SAHA 1,147.50 11 48 NARESH CHANDRA SAHA 1,147.50 12 49 SURESH CHANDRA SAHA 1,147.50 13 50 BENOY KRISHNA PODDER 1,147.50 14 51 PARESH CHANDRA SAHA 1,147.50 15 52 DILIP KUMAR SAHA 1,147.50 16 53 RAMESH CHANDRA SAHA 1,147.50 17 55 FARHAD BANU ISLAM 38.25 18 56 AMINUL ISLAM KHAN 765.00 19 61 SHEIKH MAHFUZ HOSSAIN 153.00 20 63 F I M MOFAZZAL HOSSAIN 5,125.50 21 65 SAJED AHMED KHAN 994.50 22 68 QUAZI MUHAMMAD SHAHIDULLAH (JT) 38.25 23 96 REGENT MOGHUL FUND LIMITED 6,300.00 24 104 MD. GOLAM MOWLA 2,295.00 25 117 SABERA ZAMAN 76.50 26 126 HEMYET UDDIN AHMED 497.25 27 141 TUBLA 76.50 28 149 SK. ALIMUL HAQUE 1,989.00 29 160 JALAL 229.50 30 161 SIDDIQUA CHOWDHURY 1,530.00 31 162 KAMAL 76.50 32 163 M. -

STATE of CIVIL-MILITARY RELATIONS in PAKISTAN a Study of 5 Years: 2013-2018

STATE OF CIVIL-MILITARY RELATIONS IN PAKISTAN A Study of 5 Years: 2013-2018 Pakistan Institute of Legislative Development And Transparency STATE OF CIVIL-MILITARY RELATIONS IN PAKISTAN A Study of 5 Years: 2013-2018 Pakistan Institute of Legislative Development And Transparency PILDAT is an independent, non-partisan and not-for-profit indigenous research and training institution with the mission to strengthen democracy and democratic institutions in Pakistan. PILDAT is a registered non-profit entity under the Societies Registration Act XXI of 1860, Pakistan. Copyright © Pakistan Institute of Legislative Development And Transparency - PILDAT All Rights Reserved Printed in Pakistan Published: January 2019 ISBN: 978-969-558-734-8 Any part of this publication can be used or cited with a clear reference to PILDAT. Pakistan Institute of Legislative Development And Transparency Islamabad Office: P. O. Box 278, F-8, Postal Code: 44220, Islamabad, Pakistan Lahore Office: P. O. Box 11098, L.C.C.H.S, Postal Code: 54792, Lahore, Pakistan E-mail: [email protected] | Website: www.pildat.org P I L D A T State of Civil-Military Relations in Pakistan A Study of 5 Years: 2013-2018 CONTENTS Preface 05 List of Abbreviations and Acronyms 07 Executive Summary 09 Introduction 13 State of Civil-military Relations in Pakistan: June 2013-May 2018 13 Major Irritants in Civil-Military Relations in Pakistan 13 i. Treason Trial of Gen. (Retd.) Pervez Musharraf 13 ii. The Islamabad Sit-in 14 iii. Disqualification of Mr. Nawaz Sharif 27 iv. 21st Constitutional Amendment and the Formation of Military Courts 28 v. Allegations of Election Meddling 30 vi. -

Remembering Partition: Violence, Nationalism and History in India

Remembering Partition: Violence, Nationalism and History in India Gyanendra Pandey CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS Remembering Partition Violence, Nationalism and History in India Through an investigation of the violence that marked the partition of British India in 1947, this book analyses questions of history and mem- ory, the nationalisation of populations and their pasts, and the ways in which violent events are remembered (or forgotten) in order to en- sure the unity of the collective subject – community or nation. Stressing the continuous entanglement of ‘event’ and ‘interpretation’, the author emphasises both the enormity of the violence of 1947 and its shifting meanings and contours. The book provides a sustained critique of the procedures of history-writing and nationalist myth-making on the ques- tion of violence, and examines how local forms of sociality are consti- tuted and reconstituted by the experience and representation of violent events. It concludes with a comment on the different kinds of political community that may still be imagined even in the wake of Partition and events like it. GYANENDRA PANDEY is Professor of Anthropology and History at Johns Hopkins University. He was a founder member of the Subaltern Studies group and is the author of many publications including The Con- struction of Communalism in Colonial North India (1990) and, as editor, Hindus and Others: the Question of Identity in India Today (1993). This page intentionally left blank Contemporary South Asia 7 Editorial board Jan Breman, G.P. Hawthorn, Ayesha Jalal, Patricia Jeffery, Atul Kohli Contemporary South Asia has been established to publish books on the politics, society and culture of South Asia since 1947. -

Quaid-I-Azam's Visit to the Southern Districts of NWFP

Quaid-i-Azam’s Visit to the Southern Districts of NWFP 1 ∗ ∗∗ Muhammad Aslam Khan & Muhammad Shakeel Ahmad Abstract In this paper an attempt has been made to explore the detailed achievements of Quaid-i-Azam’s visit to southern NWFP i.e Kohat, Bannu and DI. Khan. Historians always focused on Quiad’s visit to central NWFP like Islamia College Peshawar, Edward College Peshawar, Landikotal and other places, but they have missed to highlight his visit to southern NWFP. Quaid-i-Azam visited all the three Southern districts Kohat, Bannu and Dera Ismail Khan of NWFP on very short notice. Therefore no proper security arrangements were made and media did not give proper coverage to his visit. The details of Quaid’s visit to Southern NWFP is still unexplored by historians. This paper is a new addition on the existing literature on Quaid-i-Azam. Keywords: Quaid-i-Azam, NWFP, Khyber Pukhtunkhwa, Pakistan To Pakistanis, Quaid-e-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah, is their George Washington, their de Gaulle and their Churchill . Quaid-i-Azam visited NWFP thrice in his life span. For the first time, Quaid arrived in Peshawar on Sunday, the 18th of October 1936 2 and stayed for a week from 18th to the 24th of October at the Mundiberi residence of Sahibzada Abdul Qayum Khan 3. The political situations in the province were quite blurred at that time. Quaid visited Edward College and Islamia College Peshawar. He listened to the opinions of people from all shades of life and had friendly exchange of views with all of them. -

Shiism and Sectarian Conflict in Pakistan Identity Politics, Iranian Influence, and Tit-For-Tat Violence

Combating Terrorism Center at West Point Occasional Paper Series Shiism and Sectarian Conflict in Pakistan Identity Politics, Iranian Influence, and Tit-for-Tat Violence Hassan Abbas September 22, 2010 1 2 Preface As the first decade of the 21st century nears its end, issues surrounding militancy among the Shi‛a community in the Shi‛a heartland and beyond continue to occupy scholars and policymakers. During the past year, Iran has continued its efforts to extend its influence abroad by strengthening strategic ties with key players in international affairs, including Brazil and Turkey. Iran also continues to defy the international community through its tenacious pursuit of a nuclear program. The Lebanese Shi‛a militant group Hizballah, meanwhile, persists in its efforts to expand its regional role while stockpiling ever more advanced weapons. Sectarian violence between Sunnis and Shi‛a has escalated in places like Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Bahrain, and not least, Pakistan. As a hotbed of violent extremism, Pakistan, along with its Afghan neighbor, has lately received unprecedented amounts of attention among academics and policymakers alike. While the vast majority of contemporary analysis on Pakistan focuses on Sunni extremist groups such as the Pakistani Taliban or the Haqqani Network—arguably the main threat to domestic and regional security emanating from within Pakistan’s border—sectarian tensions in this country have attracted relatively little scholarship to date. Mindful that activities involving Shi‛i state and non-state actors have the potential to affect U.S. national security interests, the Combating Terrorism Center is therefore proud to release this latest installment of its Occasional Paper Series, Shiism and Sectarian Conflict in Pakistan: Identity Politics, Iranian Influence, and Tit-for-Tat Violence, by Dr. -

Who Is Who in Pakistan & Who Is Who in the World Study Material

1 Who is Who in Pakistan Lists of Government Officials (former & current) Governor Generals of Pakistan: Sr. # Name Assumed Office Left Office 1 Muhammad Ali Jinnah 15 August 1947 11 September 1948 (died in office) 2 Sir Khawaja Nazimuddin September 1948 October 1951 3 Sir Ghulam Muhammad October 1951 August 1955 4 Iskander Mirza August 1955 (Acting) March 1956 October 1955 (full-time) First Cabinet of Pakistan: Pakistan came into being on August 14, 1947. Its first Governor General was Muhammad Ali Jinnah and First Prime Minister was Liaqat Ali Khan. Following is the list of the first cabinet of Pakistan. Sr. Name of Minister Ministry 1. Liaqat Ali Khan Prime Minister, Foreign Minister, Defence Minister, Minister for Commonwealth relations 2. Malik Ghulam Muhammad Finance Minister 3. Ibrahim Ismail Chundrigar Minister of trade , Industries & Construction 4. *Raja Ghuzanfar Ali Minister for Food, Agriculture, and Health 5. Sardar Abdul Rab Nishtar Transport, Communication Minister 6. Fazal-ul-Rehman Minister Interior, Education, and Information 7. Jogendra Nath Mandal Minister for Law & Labour *Raja Ghuzanfar’s portfolio was changed to Minister of Evacuee and Refugee Rehabilitation and the ministry for food and agriculture was given to Abdul Satar Pirzada • The first Chief Minister of Punjab was Nawab Iftikhar. • The first Chief Minister of NWFP was Abdul Qayum Khan. • The First Chief Minister of Sindh was Muhamad Ayub Khuro. • The First Chief Minister of Balochistan was Ataullah Mengal (1 May 1972), Balochistan acquired the status of the province in 1970. List of Former Prime Ministers of Pakistan 1. Liaquat Ali Khan (1896 – 1951) In Office: 14 August 1947 – 16 October 1951 2. -

1 CM Naim a Sentimental Essay in Three Scenes My Essay Has an Epigraph

C. M. Naim A Sentimental Essay in Three Scenes My essay has an epigraph; it comes, with due apologies and gratitude, from the bard of St. Louis, Mo., and gives, I hope, my ramblings a structure. No! I am not Prince Hamlet, nor was meant to be; Am an attendant lord, and Urdu-wala one that will do To swell a progress, start a scene or two Or, as in the case here, Exactly three Scene 1 In December 1906, twenty-eight men traveled to Dhaka to represent U.P. at the formation of the All India Muslim League. Two were from Bara Banki, one of them my granduncle, Raja Naushad Ali Khan of Mailaraigunj. Thirty-nine years later, during the winter of 1945-46, I could be seen marching up and down the only main road of Bara Banki with other kids, waving a Muslim League flag and shouting slogans. No, I don’t imply some unbroken trajectory from my granduncle’s trip to my strutting in the street, for the elections in 1945 were in fact based on principles that my granduncle reportedly opposed. It was Uncle Fareed who first informed me that Naushad Ali Khan had gone to Dhaka. Uncle Fareed knew the family lore, and enjoyed sharing it with us boys. In an aunt’s house I came across a fading picture. Seated in a dogcart and dressed in Western clothes and a jaunty hat, he looked like a slightly rotund and mustached English squire. He had 1 been a poet, and one of his couplets was then well known even outside the family. -

The Partition of India Midnight's Children

THE PARTITION OF INDIA MIDNIGHT’S CHILDREN, MIDNIGHT’S FURIES India was the first nation to undertake decolonization in Asia and Africa following World War Two An estimated 15 million people were displaced during the Partition of India Partition saw the largest migration of humans in the 20th Century, outside war and famine Approximately 83,000 women were kidnapped on both sides of the newly-created border The death toll remains disputed, 1 – 2 million Less than 12 men decided the future of 400 million people 1 Wednesday October 3rd 2018 Christopher Tidyman – Loreto Kirribilli, Sydney HISTORY EXTENSION AND MODERN HISTORY History Extension key questions Who are the historians? What is the purpose of history? How has history been constructed, recorded and presented over time? Why have approaches to history changed over time? Year 11 Shaping of the Modern World: The End of Empire A study of the causes, nature and outcomes of decolonisation in ONE country Year 12 National Studies India 1942 - 1984 2 HISTORY EXTENSION PA R T I T I O N OF INDIA SYLLABUS DOT POINTS: CONTENT FOCUS: S T U D E N T S INVESTIGATE C H A N G I N G INTERPRETATIONS OF THE PARTITION OF INDIA Students examine the historians and approaches to history which have contributed to historical debate in the areas of: - the causes of the Partition - the role of individuals - the effects and consequences of the Partition of India Aims for this presentation: - Introduce teachers to a new History topic - Outline important shifts in Partition historiography - Provide an opportunity to discuss resources and materials - Have teachers consider the possibilities for teaching these topics 3 SHIFTING HISTORIOGRAPHY WHO ARE THE HISTORIANS? WHAT IS THE PURPOSE OF HISTORY? F I E R C E CONTROVERSY HAS RAGED OVER THE CAUSES OF PARTITION. -

The Pro-Chinese Communist Movement in Bangladesh

Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism On-Line *** Bangladesh Nurul Amin The Pro-Chinese Communist Movement in Bangladesh First Published: Journal of Contemporary Asia, 15:3 (1985) : 349-360. Taken from http://www.signalfire.org/2016/06/08/the-pro-chinese-communist-movement-in- bangladesh-1985/ Transcription, Editing and Markup: Sam Richards and Paul Saba Copyright: This work is in the Public Domain under the Creative Commons Common Deed. You can freely copy, distribute and display this work; as well as make derivative and commercial works. Please credit the Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism On-Line as your source, include the url to this work, and note any of the transcribers, editors & proofreaders above. Introduction The Communists in the Indian sub-continent started their political journey quite early, founding the Communist Party of India (CPI) in 1920. 1 After the Partition of India a section of young CPI members under the leadership of Sajjad Zahir established the Communist Party of Pakistan (CPP) in 1948. 2 By 1954 the CPP had been banned all over Pakistan. As a result, CPP started working through the Awami League (AL) and other popular organisations. The AL witnessed its first split in 1957 when it was in power. Assuming the post of Prime Minister in Pakistan, S.H. Suhrawardy pursued a pro-Western foreign policy and discarded the demand for “full provincial autonomy ” for East Pakistan (Bangladesh). The Awami League Chief Maulana Bhasani did not agree with the policy of the Prime Minister. On this ground, Maulana Bhasani left the AL and formed the National Awami Party (NAP) in 1957 with progressive forces. -

I Leaders of Pakistan Movement, Vol.I

NIHCR Leadersof PakistanMovement-I Editedby Dr.SajidMehmoodAwan Dr.SyedUmarHayat National Institute of Historical and Cultural Research Centre of Excellence, Quaid-i-Azam University Islamabad - Pakistan 2018 Leaders of Pakistan Movement Papers Presented at the Two-Day International Conference, April 7-8, 2008 Vol.I (English Papers) Sajid Mahmood Awan Syed Umar Hayat (Eds.) National Institute of Historical and Cultural Research Centre of Excellence, Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad – Pakistan 2018 Leaders of Pakistan Movement NIHCR Publication No.200 Copyright 2018 All rights reserved. No part of this publication be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing from the Director, National Institute of Historical and Cultural Research, Centre of Excellence, Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad. Enquiries concerning reproduction should be sent to NIHCR at the address below: National Institute of Historical and Cultural Research Centre of Excellence, New Campus, Quaid-i-Azam University P.O. Box 1230, Islamabad-44000. Tel: +92-51-2896153-54; Fax: +92-51-2896152 Email: [email protected] or [email protected] Website: www.nihcr.edu.pk Published by Muhammad Munir Khawar, Publication Officer Formatted by \ Title by Khalid Mahmood \ Zahid Imran Printed at M/s. Roohani Art Press, Sohan, Express Way, Islamabad Price: Pakistan Rs. 600/- SAARC countries: Rs. 1000/- ISBN: 978-969-415-132-8 Other countries: US$ 15/- Disclaimer: Opinions and views expressed in the papers are those of the contributors and should not be attributed to the NIHCR in any way. Contents Preface vii Foreword ix Introduction xi Paper # Title Author Page # 1. -

A Factor in East Pakistan's Separation: Political Parties Or

A Factor in East Pakistan’s Separation: Political Parties or Leadership Rizwan Ullah Kokab Massarrat Abid The separation of East Pakistan was culmination of the weakness of certain institutions of Pakistan’s political system. This failure of the institutions was in turn the result of the failure of the leadership of Pakistan who could not understand the significance of the political institutions and could not manoeuvre the institutions for the strength and unity of Pakistan. Like in every political system the political parties were one of the major institutions in Pakistan which could enable the federation of Pakistan to face the challenge of separatism successfully. This paper will examine how any national political party could not grow and mature in Pakistan and thus a deterrent of the separatism could not be established. The paper will also reveal that the political parties were not strengthened by the leaders who always remained stronger than the parties and continued driving the parties for the sake of their personal political motives. The existence of political parties in any federation provides the link among various diverse units of the state. The parties bring the political elements of different regions close on the basis of common ideology and programme. In return, these regions establish their close ties with the federation. The national, instead 2 Pakistan Vision Vol. 14 No. 1 of the regional political parties, guarantee the national integration and become an agent of unity among the units and provinces. The conspiracies against the state often take place by the individuals while the party culture often supports the issue-based politics.