The Case of District Administration in Amparai, Sri Lanka

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Part 5: List of Annexes

PART 5: LIST OF ANNEXES Annex 1: Letter of Endorsement Annex 2: Site Description and Maps Annex 3: Climate change Vulnerability and Adaptation Summary Annex 4: Incremental Cost Analysis Annex 5: Stakeholder Involvement Plan Annex 6: List of contacts Annex 7: Socioeconomic Status Report Annex 8: Monitoring and Evaluation Plan Annex 9: Bibliography Annex 10: Logical Framework Analysis Annex 11: Response to STAP Review Annex 12: Letter of Commitment- Coast Conservation Department Annex 13: Letter of Commitment- Ministry of Environment Annex 14: Letter of Commitment- International Fund for Agricultural Development _________________________________________________________________________________________________51 Tsunami Coastal Restoration in Eastern Sri Lanka Annex 2: Site Description and Maps Preamble The project is designed for the restoration and rehabilitation of coastal ecosystems. The initial emphasis of this five-year project will be on developing a scientifically based, low-cost, community-based approach to rehabilitating key coastal ecosystems at specific sites in the East Coast and facilitating replication of these techniques all along the East Coast (and in due course other tsunami-affected coasts). Three sites representing three major ecosystems – mangroves, coastal lagoons, and sand dunes –have been identified for piloting these themes. The selection was based on outputs from the Threats Analysis and the following criteria. 1. Hotspot analysis: sites where the tsunami effect was severe on the ecosystems and post tsunami reconstructions are in progress, global/national biodiversity importance exist, concentration of various resource users and their high dependency over the available resources exist and user conflicts exist. 2. Accessibility: accessibility by road was a criterion for selecting pilot sites 3. Absence of ongoing management and monitoring projects: sites at which on-going projects have not being considered for selection 4. -

Support for Professional and Institutional Capacity Enhancement (SPICE) April – June 2016 Quarterly Report Submitted to USAID/Sri Lanka

Support for Professional and Institutional Capacity Enhancement (SPICE) April – June 2016 Quarterly Report Submitted to USAID/Sri Lanka This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. Grantee: Counterpart International Associates: Management Systems International (MSI) International Center for Not-for-Profit Law (ICNL) International Foundation for Electoral Systems (IFES) GCSS Associate Cooperative Agreement Number: DFD-A-00-09-00141-00 Cooperative Agreement Number: AID 383-LA-13-00001 Counterpart International 2345 Crystal Drive, Suite 301 Arlington, VA 22202 Telephone: 703.236.1200 CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 Operational Context 5 Achievements 5 Operational Highlights 6 Challenges 6 Programming Priorities in the Next Quarter 6 POLITICAL CONTEXT 7 ANALYSIS 8 SUMMARY OF ACTIVITIES 9 Program Administration and Management 9 Component 1. Support Targeted National Indigenous Organizations to Promote Pluralism, Rights and National Discourse and Support Regional Indigenous Organizations to Promote Responsive Citizenship and Inclusive Participation 10 Component 2. Strengthen Internal Management Capacity of Indigenous Organizations 29 Capacity Building Process for SPICE Grantees 29 Capacity-Building Support to USAID’s Development Grants Program (DGP) 30 Community Organizations’ Role and Ethos: Value Activism through Leaders’ Understanding Enhancement Support (CORE VALUES) Training 30 Civil Society Strengthening – Operational Environment and Regulatory Framework 32 PROJECT MANAGEMENT AND MONITORING -

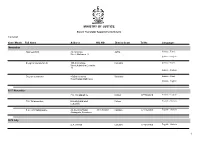

Name List of Sworn Translators in Sri Lanka

MINISTRY OF JUSTICE Sworn Translator Appointments Details 1/29/2021 Year / Month Full Name Address NIC NO District Court Tel No Languages November Rasheed.H.M. 76,1st Cross Jaffna Sinhala - Tamil Street,Ninthavur 12 Sinhala - English Sivagnanasundaram.S. 109,4/2,Collage Colombo Sinhala - Tamil Street,Kotahena,Colombo 13 Sinhala - English Dreyton senaratna 45,Old kalmunai Baticaloa Sinhala - Tamil Road,Kalladi,Batticaloa Sinhala - English 1977 November P.M. Thilakarathne Chilaw 0777892610 Sinhala - English P.M. Thilakarathne kirimathiyana East, Chilaw English - Sinhala Lunuwilla. S.D. Cyril Sadanayake 26, De silva Road, 331490350V Kalutara 0771926906 English - Sinhala Atabagoda, Panadura 1979 July D.A. vincent Colombo 0776738956 English - Sinhala 1 1/29/2021 Year / Month Full Name Address NIC NO District Court Tel No Languages 1992 July H.M.D.A. Herath 28, Kolawatta, veyangda 391842205V Gampaha 0332233032 Sinhala - English 2000 June W.A. Somaratna 12, sanasa Square, Gampaha 0332224351 English - Sinhala Gampaha 2004 July kalaichelvi Niranjan 465/1/2, Havelock Road, Colombo English - Tamil Colombo 06 2008 May saroja indrani weeratunga 1E9 ,Jayawardanagama, colombo English - battaramulla Sinhala - 2008 September Saroja Indrani Weeratunga 1/E/9, Jayawadanagama, Colombo Sinhala - English Battaramulla 2011 July P. Maheswaran 41/B, Ammankovil Road, Kalmunai English - Sinhala Kalmunai -2 Tamil - K.O. Nanda Karunanayake 65/2, Church Road, Gampaha 0718433122 Sinhala - English Gampaha 2011 November J.D. Gunarathna "Shantha", Kalutara 0771887585 Sinhala - English Kandawatta,Mulatiyana, Agalawatta. 2 1/29/2021 Year / Month Full Name Address NIC NO District Court Tel No Languages 2012 January B.P. Eranga Nadeshani Maheshika 35, Sri madhananda 855162954V Panadura 0773188790 English - French Mawatha, Panadura 0773188790 Sinhala - 2013 Khan.C.M.S. -

Ampara District Secretariat for the Year 2016

ලාක කාය සාධන ලාතාල හා 燒귔 tUlhe;j nrayhw;W mwpf;ifAk; fzf;fwpf;ifAk ; ANNUAL PERFORMANCE REPORT & ACCOUNTS 2015 1 ලාක කාය සාධන ලාතාල හා 燒귔 tUlhe;j nrayhw;W mwpf;ifAk; fzf;fwpf;ifAk; ANNUAL PERFORMANCE REPORT & ACCOUNTS 2016 뷒ස්ත්රික්ලේකමකකායායඅපාර khtl;l nrayfk; - mk;ghiw DISTRICT SECRETARIAT AMPARA 2 Subject Page No. 01. District Administration 1.1 Massage of the District Secretary 06 1.2 Mission,Vision,Statement, Objectives & Activities of the District Secretariat 09 1.3 Historical Background of Ampara District 10 1.4 District Secretariat and Attached Institution 12 1.5 Grama Niladhary Divisions and Organization chart of the District Secretariat 13 1.6 Duty and Responsible of the Administration Branch of the District Secretariat 16 1.7 Cadre Details of the District Secretariat & Divisional Secretariats 17 1.8 Details of Government Quarters assigned to the District Secretariat 18 1.9 Details of Charges for Circuit Bungalow 19 1.10 Details of Income earned from Circuit Bungalow 20 1.11 Infomation of District Secretariat 21 02 Populations 2.1 Total Population of Ampara District by DS Division on Sex Ratio 23 2.2 Total Population of Ampara District by DS Division on Age Group 24 03. Agriculture 3.1 Agriculture Industries of Ampara District 26 3.2 Targeted, Sown and Harvested Extent of Paddy by DS Division 2016 27 3.3 Details of Crops Cultivation DS Division Level 2016 (Vegetable) 28 3.4 Details of Crops Cultivation DS Division Level 2016(Other Field Crops) 29 04. -

Divisional Secretariat Contact Details Last Update - 2019.02.26

Divisional Secretariat Contact Details Last Update - 2019.02.26 Divisional Secratariat Divisional Secretary Additional Divisional Secretary District E-mail Address Divisional Secratariat Address Telephone Number Fax Number Name Telephone Number Mobile Number Name Telephone Number Mobile Number Ampara Ampara [email protected] Addalaichenai Addalaichenai 0672277336 0672279213 J Liyakath Ali 0672055336 0778512717 TJ Athisayaraj 0672277452 0776174102 Divisional Secretariat, Dammarathana Ampara [email protected] Ampara 0632223435 0632223004 N.M.Upeksha Kumari 063-2224595 0702690042 R.Thiraviyaraj 063-2222351 0779597487 Road,Indrasarapura,Ampara Ampara [email protected] Sammanthurai Sammanthurai 0672260236 0672261124 Mr.S.L.Mohamed Haniffa 0672260236 0771098618 Mr.MM.Aseek 0672260293 07684233430 Ampara [email protected] Kalmunai South Divisional Secretariat, Kalmunai 0672229236 0672229380 M.M. Nazeer 0672229236 0772710361 T.J. Athisayaraj 0672224430 0776174102 Ampara [email protected] Padiyathalawa Divisional Secretariat Padiyathalawa 0632246035 0632246190 R.M.N.Wijayathunga 0632246045 0718480734 W.Wimansa Senewirathna 0632050856 0712508960 Ampara [email protected] Sainthamaruthu Main Street Sainthamaruthu 0672221890 0672221890 Nill Nill Nill I.M Rikas 0672056490 0777994493 Ampara [email protected] Dehiattakandiya. Divisional Secretariat, Dehiattakandiya. 027-2250167 027-2250197 Mrs.M.P.W.Shiromani. 027-2250177 0718898478 Mr.S.Partheepan 027-2250081 0714314324 -

Ampara for the Year 2017

1 ලාක කාය සාධන ලාතාල හා 燒귔 tUlhe;j nrayhw;W mwpf;ifAk; fzf;fwpf;ifAk; ANNUAL PERFORMANCE REPORT & ACCOUNTS 2017 뷒ස්ත්රික්ලේකමකකායායඅපාර khtl;l nrayfk; - mk;ghiw DISTRICT SECRETARIAT AMPARA 2 Subject Page No. 01. District Administration 1.1 Massage of the District Secretary 06 1.2 Mission,Vision,Statement, Objectives & Activities of the District Secretariat 08 1.3 Historical Background of Ampara District 09 1.4 District Secretariat and Attached Institution 11 1.5 Grama Niladhary Divisions and Organization chart of the District Secretariat 12 1.6 Duty and Responsible of the Administration Branch of the District Secretariat 15 1.7 Cadre Details of the District Secretariat & Divisional Secretariats 16 1.8 Details of Government Quarters assigned to the District Secretariat 17 1.9 Details of Charges for Circuit Bungalow 18 1.10 Details of Income earned from Circuit Bungalow 19 02 Populations 2.1 Total Population of Ampara District by DS Division on Sex Ratio 21 2.2 Percentage distribution of Population by ethnic group and D.S Division -2016 22 03. Agriculture 3.1 Paddy Cultivation 24 3.2 OFC and Other Highland Crops Cultivation 25 3.3 Fruit Crops Cultivation 26 04. Education 4.1 School Type and Medium-2017 28 4.2 National School Type and Medium-2017 29 4.3 Provincial School Type and Medium-2017 30 4.4 Education Zone and Education Division-2017 31 3 05. Development 5.1 District Secretariat development Works-(270) 2017 34 5.2 Ministry of National Policies &Economic Affairs (104) (DCB) 35 5.3 Rural Infrastructure Development Programme – 2017 36 5.4 Rural Sports Ground Development - 2017 37 5.5 Ministry of Resettlement Works-(145) 2017 39 5.6 District Development Programmes implemented by 41 District Secretariats Ampara - 2017 5.7 Activities of District Samurdhi Unit 42 5.8. -

D8dcaf526f7c4675492571fb

PEACE AUDIT 2006 Supporting an Enabling Environment for Peace in Sri Lanka Consortium of Humanitarian Agencies Part 1 Published by: Consortium of Humanitarian Agencies 86, Rosmead Place, Colombo 07, Sri Lanka. Tel/fax: (94-11) 4610943/4; web: www.humanitarian-srilanka.org The Consortium of Humanitarian Agencies is an association of agencies functioning as a network of humanitarian agencies in Sri Lanka. CHA, over the past eight years has developed into a full-fledged secretariat with its own specific capabilities. Its comparative advantages are: being a network having an excellent tool to disseminate information; and weight in discussions and in lobbying due to its large membership and linkages both local and overseas. © Consortium of Humanitarian Agencies First published: September 2006 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical or photo-copying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the Consortium of Humanitarian Agencies. It is distributed on the understanding that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise be sold, lent, hired or otherwise circulated without the prior consent of the CHA. Cover designed by: “Ozhone” Printed by: Design Systems, Colombo 10. Tel: 011 4936823 ISBN 955-1041-24-0 ii Foreword Part 1 his report, titled ‘Peace Audit 2006 - Supporting an Enabling Environment for Peace in Sri Lanka’, is a study aimed at contributing to the creation of conflict sensitive capacity of humanitarian and de T velopment actors in Sri Lanka and is presented as a sequel to the Peace Audit CHA conducted in 2004. -

Ampara District Jummah Mosqe Sno Regd

AMPARA DISTRICT JUMMAH MOSQE SNO REGD. NO. Name Type Address City District 1 R/0278/AM/01 MASJIDUL KABEER JUMMA MOSQUE JM MARUTHAMUNAI KALMUNAI AMPARA 2 R/0303/AM/02 KHAJA JOWHARALISHA MACCAM JM SAINTHAMARUTHU SAINTHAMARUTHU AMPARA 3 R/0318/AM/03 NINTAVUR JUMMA MOSQUE JM NINTAVUR NINTAVUR AMPARA 4 R/0406/AM/04 MASJIDUN NOOR JUMMA MOSQUE JM MARUTHAMUNAI NORTH KALMINAI AMPARA 5 R/0410/AM/05 AKKARAIPATTU TOWN JUMMA MOSQUE JM AKKARAIPATTU AKKARAIPATTU AMPARA 6 R/0434/AM/08 MASJIDUL JALALIYA JUMMA MOSQUE JM PUDDAMPAI, AKKARAIPATTU AKKARAIPATTU AMPARA 7 R/0445/AM/09 NAIPETTIMUNAI JUMMA GRAND MOSQUE JM KALMUNAI KALMUNAI AMPARA 8 R/0461/AM/10 PASARICHCHENAI JUMMA MOSQUE JM POTTUVIL POTTUVIL AMPARA PANAMAIPATTU POTTUVIL JUMMA 9 R/0528/AM/11 JM POTTUVIL POTTUVIL AMPARA MOSQUE 10 R/0531/AM/12 AKKARAIPATTU GRAND JUMMA MOSQUE JM AKKARAIPATTYU AKKARAIPATTU AMAPRA 11 R/0594/AM/13 RAHUMANIYA JUMMA MOSQUE JM MAIN STREET, PADIYATALAWA AMPARA MAVADIPALLY MUHIYIDEEN PALLIVASAL 12 R/0628/AM/14 JM MAVADIPPALLY, KARAITIVU AMPARA JUMMA MOSQUE 13 R/0664/AM/15 PATTIYADIPITTY JUMMA MOSQUE JM AKKARAIPATTU AKKARAIPATTU AMPARA 14 R/0699/AM/16 MASJID MUHAMMADI JUMMA MOSQUE JM DIVISION NO. 3, KALMUNAIKUDY, KALMUNAI AMPARA 15 R/0711/AM/18 GRAND MOSQUE JM ADDALAICHENAI ADDALAICHENAI AMPARA 16 R/0725/AM/19 KALMUNAIKUDY JUMMA MOSQUE JM KALMUNAI KALMUNAI AMPARA 17 R/0746/AM26 AKKARAIPATTU JUMMA NEW MOSQUE JM AKKARAIPATTU AKKARAIPATTU AMPARA 18 R/.0747/AM/27 JUMMA MOSQE JM 15TH COLONY, ANNAMALAI. KALMIUNAI AMPARA 19 R/0748/AM28 JUMMA MOSQE JM MAIN STREET, SAINTHAMARUTHU, -

Eastern Province

Resettlement Due Diligence Report June 2017 SRI: Second Integrated Road Investment Program Eastern Province Prepared by Road Development Authority, Ministry of Higher Education and Highways for the Government of Sri Lanka and the Asian Development Bank. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 30 May 2017) Currency unit – Sri Lanka Rupee (SLRl} SLR1.00 = $ 0.00655 $1.00 = Rs 152.63 ABBREVIATIONS ADB - Asian Development Bank DSD - Divisional Secretariat Division DS - Divisional Secretariat EP - Eastern Province EPL - Environmental Protection License DDR - Due Diligence Report FGD - Focus Group Discussion GDP - Gross Domestic Production GoSL - Government of Sri Lanka GN - Grama Niladari GND - Grama Niladari Division GRC - Grievance Redress Committee GSMB - Geological Survey and Mines Bureau HH - Household iRoad - Integrated Road Investment Program iRoad 2 - Second Integrated Road Investment Program IR - Involuntary Resettlement MoHEH - Ministry of Higher Education and Highways NWS&DB - National Water Supply and Drainage Board OFC - Other Field Crops PS - Pradeshiya Sabha PPE - Personal Protective Equipment’s RDA - Road Development Authority RF - Resettlement Framework ROW - Right of Way SAPE - Survey and Preliminary Engineering SLR - Sri Lankan Rupees This resettlement due diligence report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. -

Ampara District Located in the South East of Sri Lanka Belongs to the Eastern Province

PART - I 1. INTRODUCTION The Lessons Learnt and Reconciliation Commission (LLRC) of 2011 recommended that “a land use plan for each District in the North and East should be developed with the participation of district and national experts drawn from various relevant disciplines to guide the district administration in land conservation and alienation in order to ensure protection of environment and bio-diversity; sustainable economic development; leisure and recreational standards; religious, cultural and archeological sites with a view to improving the quality of life of the present and future generations”. The preparation of the plans was entrusted to the Land Use Policy Planning Department (LUPPD). The LUPPD started the planning process by establishing two expert groups, one at the National Level and the other at the District Level. Field work was commenced in 2013. Initially the available land use maps were updated to study the current patterns of land use and subsequently major land use issues were identified based on the field investigations. Recommendations to address the land use issues were formulated and these were presented to the Expert Groups and Stakeholders for their views and comments. The plan for the district has been prepared incorporating the views and comments of the Expert Groups and the Stakeholders. The Plan is mainly divided into two parts. Part I provides the background for the plan. Part II gives the land use plan. 2. DISTRICT PROFILE 2.1 Introduction Ampara District located in the South East of Sri Lanka belongs to the Eastern Province. It is bounded by the Polonnaruwa&Batticaloa Districts in the North, the Indian Ocean in the East, HambanthotaDistrictin the South and Monaragala, Badulla&MataleDistirctsin the West (Figure1). -

Ampara District – 2007

BASIC POPULATION INFORMATION ON AMPARA DISTRICT – 2007 Preliminary Report Based on Special Enumeration – 2007 Department of Census and Statistics October 2007 ISBN 978-955-577-615-8 Foreword The Department of Census and Statistics (DCS), carried out a special enumeration in Eastern province and in Jaffna district in Northern province. The objective of this enumeration is to provide the necessary basic information needed to formulate development programmes and relief activities for the people. This preliminary publication for Ampara district has been compiled from the reports obtained from the District based on summaries prepared by enumerators and supervisors. A final detailed information will be disseminated after the computer processing of questionnaires. This preliminary release gives some basic information for Ampara district, such as population by divisional secretary’s division, urban/rural population, sex, age (under 18 years and 18 years and over) and ethnicity. Data on displaced persons due to conflict or tsunami are also included. Some important information which is useful for regional level planning purposes are given by Grama Niladhari Divisions. This enumeration is based on the usual residents of households in the district. These figures should be regarded as provisional. I wish to express my sincere thanks to the staff of the department and all other government officials and others who worked with dedication and diligence for the successful completion of the enumeration. I am also grateful to the general public for extending their fullest co‐operation in this important undertaking. This publication has been prepared by Population Census Division of this Department. D.B.P. Suranjana Vidyaratne Director General of Census and Statistics 10th October 2007 Department of Census and Statistics, 15/12, Maitland Crescent, Colombo 7. -

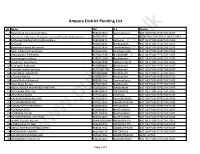

Ampara District Pending List

Ampara District Pending List SN Name NIC D S Reason 1 Moahamed Ismail Asmath Banu 958181590 V Sammanthurai NOT MENTION EFFECTIVE DATE 2 රන්හශහ ො බණ්ඩාරාහේ ව්ලණා ජයහෙත්ති මැණිහේ තිකරත්ෙ 867851437V ATTACHED FEW RESULT SHEET ONLY 3 M0hamed Habbas FathimaAfrose Banu 955013867V Kalmunai NOT MENTION EFFECTIVE DATE 4 K.Tharani 945663260V Navithanvell NOT MENTION EFFECTIVE DATE 5 Bazeer Mohamed Musammil 882562263V Sammanthurai NOT MENTION EFFECTIVE DATE 6 Meer Lebbe Fathima Shifna 925062359V Sammanthurai NOT MENTION EFFECTIVE DATE 7 Uthayakumar Ketheesha 957903274V Navithanvell NOT MENTION EFFECTIVE DATE 8 Arasanayagam Meena 948582198V Navithanvell NOT MENTION EFFECTIVE DATE 9 Jeyakumar Jeyaletsumi 947962752V Kalmunai North NOT MENTION EFFECTIVE DATE 10 Sivalingam Kugapriya 945683430V Navithanvell NOT MENTION EFFECTIVE DATE 11 Uthayakirinathan januska 9571929447V Navithanvell NOT MENTION EFFECTIVE DATE 12 Loganathan Ushanthani 927393158V Navithanvell NOT MENTION EFFECTIVE DATE 13 Srisankar Panuja 955852990 V Navithanvell NOT MENTION EFFECTIVE DATE 14 Junaid Mafas Mohamed 902191674V Sammanthurai NOT MENTION EFFECTIVE DATE 15 Rajan Pious Ranuja 957542530V Navithanvell NOT MENTION EFFECTIVE DATE 16 ABDUL BAZEER MOHAMED HAMTHAN 950060506V IRAKKAMAM NOT MENTION EFFECTIVE DATE 17 SRITHARAN PRINTHA 948600897V THIRUKKOVIL NOT MENTION EFFECTIVE DATE 18 JEEVARASA VILJINI 937772246V POTTUVIL NOT MENTION EFFECTIVE DATE 19 PARAMESWARAN NILOJINI 947832697V ALAYADIVEMBU NOT MENTION EFFECTIVE DATE 20 YUGAVARNAN KIRIJJA 947602160V SAMMANTHURAI NOT MENTION EFFECTIVE