Part 5: List of Annexes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Performance Report-2010-English

1 2 List of Tables Page Table 1.1: Special Project Proposals Qualified for Funding 5 Table 1.2: Progress of Action Plan Activities in 2010. 6 Table 2.1: Rehabilitation and Construction of Water Bodies in 2010 7 Table 2.2: Rehabilitation of PA Road Network in 2010 8 Table 2.3: Survey and Demarcation of Protected Area Boundaries in 2010. 9 Table 2.4: Sign Boards Established in 2010 10 Table 2.5: Management of Grasslands in Wildlife Regions in 2010 11 Table 2.6: Removal of Invasive Species in 2010 11 Table 2.7: Maintenance of Fire Belts in 2010 11 Table 2.8: Wildlife Conservation Activities under Moragahakanda Project in 2010 12 Table 2.9: Wildlife Conservation Activities under Weheragala Project in 2010 12 Table 3.1: Number of Cases Prosecuted in 2010 14 Table 3.2: Progress of Action Plan Activities for 2010 15 Table 4.1: Regional Distribution of Elephant Deaths from 2006-2010 16 Table 4.2: Regional Distribution of Human Deaths 17 Table 4.3: Regional Distribution of Injuries to Human due to Elephant Attacks (2006-2010) 18 Table 4.4: Regional Distribution of Property Damages (2006-2010) 19 Table 4.5: New Electric Fences erected in 2010 21 Table 4.6: Procurement of Thunder Flares and Serphent Flares in 2010 22 Table 4.7: Distribution of the Thunder Flares and Serphent Flares in 2010 22 Table 4.8: Compensation Paid in 2010 22 Table 4.9: Capture and Translocation of Elephants in 2010 23 Table 4.10: Elephant Drives in 2010 24 Table 4.11: Gajamithuro Project – Progress in 2010 24 Table 5.1: Research Studies Undertaken by DWC Staff in 2010 26 Table 5.2: Collaborative Research Projects for 2010 27 Table 5.3: Short-term Special Training Programmes Conducted for Wildlife Officers in 2010 29 Table 5.4 : Regular Training Programmes Conducted at NWTRC in 2010 30 Table 5.5 Awareness programmes conducted by NWTRC 31 Table 5.6 Financial Progress of NWTRC 31 Table 5.7: Foreign Training Programmes Participated by Wildlife Officers in 2010 32 Table 5.8: Seminars, Exhibitions and Awareness Programmes Conducted in 2010. -

Download Brochure

Redefining Beach Living The first of it’s kind, Oceanfront Condos presents a luxurious beachside option for those looking for a place to call home. Get away from bustling work life and enjoy gorgeous ocean views, spacious living spaces, and tranquil natural surroundings. With 54 condominiums in 4 identical building footprints and located only 260 kilometers away from the Capital of Sri Lanka, Oceanfront Condos is a home away from home. Regular Flights available from Colombo to Trincomalee - China Bay Sri Lanka Floor Plans 3 BEDROOM 2 BEDROOM TYPE A TYPE B 122.14 SQM 110.00 SQM 1314.23 SQFT 1183.60 SQFT Ground & Level 1 Ground, Level 1, Level 2 & Level 3 Ocean & Beach Ocean & Beach The above plans are subject to change as may be approved by the relevant authority. Areas are approximate measurements and subject to final survey. Plans are not to scale. 3 BEDROOM 3 BEDROOM TYPE C TYPE D (Penthouse) 214.53 SQM 177.29 SQM 2308.34 SQFT 1907.64 SQFT PANORAMIC PANORAMIC Level 2 Level 3 Ocean & Beach Ocean & Beach The above plans are subject to change as may be approved by the relevant authority. Areas are approximate measurements and subject to final survey. Plans are not to scale. Places of Interest Fort Frederick Harbour Built by the Portuguese in 1623 using the remains of the Koneswaram Trincomalee is the 2nd largest natural harbour in the world. Originally used Hindu Temple, it was rebuilt by the Dutch in 1665 and renamed as by the Chola army in 900AD, it was constantly fought over between the Sri Fort Frederick until the British took over in 1782. -

Sri Lanka Tourism: Poised for Growth

17 JUNE 2011 SRI LANKA TOURISM: POISED FOR GROWTH Inshita Wij Senior Associate www.hvs.com HVS India| 6th Floor, Building 8-C, DLF Cyber City Phase II, Gurgaon 122 002 INDIA Following the end of a three-decade long civil war in 2009, Sri Lanka has witnessed unprecedented growth. With a real GDP growth rate of 8% in 2010, a jump of 125.2% in the stock market in 2009, and 32% year-on-year growth in tourist arrivals in 2010, Sri Lanka is on its way to becoming a major tourism destination in South Asia. In the past one year, HVS India has received numerous inquiries about Sri Lanka from hotel operators, investors, and developers. These queries rightly come at a time when the country’s total rooms supply needs to be more than doubled in the next five years to meet the tourist arrivals targets. We have, therefore, in this article tried to highlight the current tourism landscape, highlighting the projected shortage of hotel rooms in the next five years and discussed in detail the factors that would help in tourism growth in the long term. We have also highlighted the future trends and challenges in the Sri Lankan hotel industry. The Current Tourism Landscape Sri Lanka witnessed a EXHIBIT 1: TOURIST ARRIVALS: 2000-2010 strong upsurge in tourism after the end of the civil 700,000 654,477 war in 2009. Tourism1, which forms 0.6% of the 600,000 549,308 total GDP of the country, 500,000 438,475 400,414 393,171 was one of the fastest 400,000 growing sectors in the 300,000 economy, growing by 200,000 39.8% in 2010 over 2009. -

MICE-Proposal-Sri-Lanka-Part-2.Pdf

Sri Lanka East Coast Region Trincomalee , a port city on the northeast coast of Sri Lanka. Set on a peninsula, Fort Frederick was built by the Portuguese in the 17th century. Trincomalee is one of the main centers of Tamil speaking culture on the island. The beaches are used for scuba diving, snorkeling and whale watching. The city also has the largest Dutch Fort in Sri Lanka. Best for: blue-whale watching. Arugam Bay, Arugam Bay is a unique and spectacular golden sandy beach on the East coast, located close to Pottuvil in the Ampara district. It is one of the best surfing spots in the world and hosts a number of international surfing competitions. Best for: Surfing & Ethnic Charm The beach of Pasikudah, which boasts one of the longest stretches of shallow coastline in the world. Sri Lanka ‘s Cultural Triangle Sri Lanka’s Cultural triangle is situated in the centre of the island and covers an area which includes 5 World Heritage cultural sites(UNESCO) of the Sacred City of Anuradhapura, the Ancient City of Polonnaruwa, the Ancient City of Sigiriya, the Ancient City of Dambulla and the Sacred City of Kandy. Due to the constructions and associated historical events, some of which are millennia old, these sites are of high universal value; they are visited by many pilgrims, both laymen and the clergy (prominently Buddhist), as well as by local and foreign tourists. Kandy the second largest city in Sri- Lanka and a UNESCO world heritage site, due its rich, vibrant culture and history. This historic city was the Royal Capital during the 16th century and maintains its sanctified glory predominantly due to the sacred temples. -

Category: Research Article Scarcity of Drinking Water in Pottu Sri Lanka Esearch Article Drinking Water in Pottuvil Water Supply

Volume-5 ISSN: 2362-0080 Issue- I Rajarata University Journal June-2020 www.ruj.ac.lk/journals/ Category: Research Article Scarcity of Drinking Water in Pottuvil Water Supply Scheme, Sri Lanka *1Mohideenbawa Riswan & 2Pahurdeen Ishaq *1Department of Sociology, South Eastern University of Sri Lanka, Oluvil, Sri Lanka 2National Water Supply & Drainage Board (NWSDB), Regional Office, Batticaloa, Sri Lanka ARTICLE DETAILS ABSTRACT Article History Water is an essential resource with regards to livelihoods, health and a Published Online: 30 June 2020 socio-economic development perspective since there are no substitutes for it. And increasing population, wasteful consumption, rapid climate Keywords change and unplanned socio-economic development have put great Drinking Water, Scarcity, Borehole, HedaOya, Water-Source, NWSDB, pressure on water resources. The anticipated climate and socio WSS, CBOs. economic changes may further increase water stress. Due to this issue, *Corresponding Author many rural people in Pottuvil Water Supply Scheme, facing numerous E-mail:[email protected] problems to receive safe drinking water for their daily requirements. The study has been done in order to find out the nature of drinking water scarcity and causes contributing on it in the study community. This study used a mixed method of analysis with qualitative and quantitative data which have gathered from primary (Interview with key-informant, direct observation) and secondary (statistical record of National Water Supply and Drainage Board, government departments, previously conducted researches and electronic materials) sources. Finally, this study found that the water scarcity prevails at high level in the study area, and it has been studied that the implementation of HedaOya water supply project would be a permanent solutions for the existing water scarcity of this study community. -

Annual Performance Report of the District Secretariat

ANNUAL PERFORMANCE REPORT FOR THE YEAR 2019, TRINCOMALEE 뷒ස්ත්රි槊 ලේක කායාලය,ක臊ල臊ය,ි槔ණාමලය khtl;lr; nrayfk;, jpUNfhzkiy District Secretariat, Kachcheri, Trincomalee වාික කායස්ත්ාධන වාතාව tUlhe;j nraw;jpwd; mwpf;if ANNUAL PERFORMANCE REPORT 2019 0 ANNUAL PERFORMANCE REPORT FOR THE YEAR 2019, TRINCOMALEE Annual Performance Report for the year 2019 District Secretariat, Trincomalee Expenditure Head No 271 Contents Page Chapter 01 - Institutional Profile ………………………………………………………… 2-10 Chapter 02 – Progress and the Future Outlook …………………………………... 11 Chapter 03 - Overall Financial Performance for the Year ……………….……. 12-41 Chapter 04- Performance of the achieving Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) ………………………………………………. 42-45 Chapter 05 - Human Resource Profile ………………………………………………… 46-48 Chapter 06– Compliance Report ………………………………………………………… 49-54 1 ANNUAL PERFORMANCE REPORT FOR THE YEAR 2019, TRINCOMALEE Chapter 01 - Institutional Profile 1.1. Introduction Trincomalee District - A Glimpse The Boundary Trincomalee, a picturesque city with a natural 2arbor, scenic beauty, and military, commercial and historical importance, is situated in the eastern coast of Sri Lanka. Trincomalee District is boarded with Mulathivu District in North, Anuradhapura District in West and Polonnaruwa and Batticaloa Districts in the South. The History The history of Trincomalee goes back to a time of immemorial. The Mahavamsa & Chulavamsa, the two great chronicles, mention present Trincomalee as “Gokanna” , Gokarna, and “Gonagamaka” During the Anuradhapura and Polonnaruwa periods of island’s history. The Administration The Trincomalee District located in the center of Eastern Province covering an area of 2,727 square kilometers. The district is divided into 11 Divisional Secretary’s Divisions for administrative purpose. The DS Divisions are further sub-divided into 230 Grama Niladhari Divisions. -

Support for Professional and Institutional Capacity Enhancement (SPICE) April – June 2016 Quarterly Report Submitted to USAID/Sri Lanka

Support for Professional and Institutional Capacity Enhancement (SPICE) April – June 2016 Quarterly Report Submitted to USAID/Sri Lanka This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. Grantee: Counterpart International Associates: Management Systems International (MSI) International Center for Not-for-Profit Law (ICNL) International Foundation for Electoral Systems (IFES) GCSS Associate Cooperative Agreement Number: DFD-A-00-09-00141-00 Cooperative Agreement Number: AID 383-LA-13-00001 Counterpart International 2345 Crystal Drive, Suite 301 Arlington, VA 22202 Telephone: 703.236.1200 CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 Operational Context 5 Achievements 5 Operational Highlights 6 Challenges 6 Programming Priorities in the Next Quarter 6 POLITICAL CONTEXT 7 ANALYSIS 8 SUMMARY OF ACTIVITIES 9 Program Administration and Management 9 Component 1. Support Targeted National Indigenous Organizations to Promote Pluralism, Rights and National Discourse and Support Regional Indigenous Organizations to Promote Responsive Citizenship and Inclusive Participation 10 Component 2. Strengthen Internal Management Capacity of Indigenous Organizations 29 Capacity Building Process for SPICE Grantees 29 Capacity-Building Support to USAID’s Development Grants Program (DGP) 30 Community Organizations’ Role and Ethos: Value Activism through Leaders’ Understanding Enhancement Support (CORE VALUES) Training 30 Civil Society Strengthening – Operational Environment and Regulatory Framework 32 PROJECT MANAGEMENT AND MONITORING -

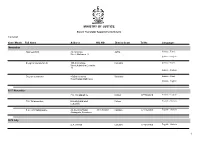

Name List of Sworn Translators in Sri Lanka

MINISTRY OF JUSTICE Sworn Translator Appointments Details 1/29/2021 Year / Month Full Name Address NIC NO District Court Tel No Languages November Rasheed.H.M. 76,1st Cross Jaffna Sinhala - Tamil Street,Ninthavur 12 Sinhala - English Sivagnanasundaram.S. 109,4/2,Collage Colombo Sinhala - Tamil Street,Kotahena,Colombo 13 Sinhala - English Dreyton senaratna 45,Old kalmunai Baticaloa Sinhala - Tamil Road,Kalladi,Batticaloa Sinhala - English 1977 November P.M. Thilakarathne Chilaw 0777892610 Sinhala - English P.M. Thilakarathne kirimathiyana East, Chilaw English - Sinhala Lunuwilla. S.D. Cyril Sadanayake 26, De silva Road, 331490350V Kalutara 0771926906 English - Sinhala Atabagoda, Panadura 1979 July D.A. vincent Colombo 0776738956 English - Sinhala 1 1/29/2021 Year / Month Full Name Address NIC NO District Court Tel No Languages 1992 July H.M.D.A. Herath 28, Kolawatta, veyangda 391842205V Gampaha 0332233032 Sinhala - English 2000 June W.A. Somaratna 12, sanasa Square, Gampaha 0332224351 English - Sinhala Gampaha 2004 July kalaichelvi Niranjan 465/1/2, Havelock Road, Colombo English - Tamil Colombo 06 2008 May saroja indrani weeratunga 1E9 ,Jayawardanagama, colombo English - battaramulla Sinhala - 2008 September Saroja Indrani Weeratunga 1/E/9, Jayawadanagama, Colombo Sinhala - English Battaramulla 2011 July P. Maheswaran 41/B, Ammankovil Road, Kalmunai English - Sinhala Kalmunai -2 Tamil - K.O. Nanda Karunanayake 65/2, Church Road, Gampaha 0718433122 Sinhala - English Gampaha 2011 November J.D. Gunarathna "Shantha", Kalutara 0771887585 Sinhala - English Kandawatta,Mulatiyana, Agalawatta. 2 1/29/2021 Year / Month Full Name Address NIC NO District Court Tel No Languages 2012 January B.P. Eranga Nadeshani Maheshika 35, Sri madhananda 855162954V Panadura 0773188790 English - French Mawatha, Panadura 0773188790 Sinhala - 2013 Khan.C.M.S. -

Sri Lanka Practical Information

SRI LANKA PRACTICAL INFORMATION Historically and culturally intertwined with the Indian subcontinent, but geographically separated, the tropical island nation of Sri Lanka is a biodiversity hotspot – perfect for those in search of an adventurous getaway! Khiri Travel are pleased to offer you herewith some useful tips and practical information on traveling in Sri Lanka. SRI LANKA PRACTICAL INFORMATION PASSPORTS FAST FACTS & VISAS OFFICIAL NAME Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka Visas for Sri Lanka can be obtained on arrival at the airport, but we advise travelers to apply online prior to CAPITAL CITY arriving, as this helps to avoid delays or long queues at Sri Jayawardenepura Kotte (a suburb of the commercial the airport. capital and largest city, Colombo) TOTAL AREA 65,610 km2 CURRENCY MONEY Sri Lankan rupee The currency used in Sri Lanka is the Sri Lankan Rupee. LANGUAGE International currency can be exchanged at the arrival Sinhalese lounge of the airport, however banks, moneychangers and hotels also exchange currency. Hotels will usually charge POPULATION a higher commission. You may also use ATMs for money 21.5 million exchange – Visa and MasterCards are widely acceptable, PEOPLE however Amex cards are not so popular. Sinhalese, Tamils, Moors, Burghers, Malays and Vedda Important: Be sure to advise your bank and credit card (believed to be the original indigenous group to inhabit company that you will be using your cards overseas before the island) you leave, otherwise they may report a fraud alert on your account! RELIGION Buddhism (Therevada) TIME ZONE UTC +5.30 hours HEALTH INTERNATIONAL DIALING CODE +94 Overall, Sri Lanka is a very safe destination – but there ELECTRICITY are certain risks. -

Jfcqjsptlpq Learning-Politics-From

LEARNING POLITICS FROM SIVARAM The Life and Death of a Revolutionary Tamil Journalist in Sri Lanka MARK P. WHITAKER Pluto P Press LONDON • ANN ARBOR, MI Whitaker 00 PLUTO pre iii 14/11/06 08:40:31 First published 2007 by Pluto Press 345 Archway Road, London N6 5AA and 839 Greene Street, Ann Arbor, MI 48106 www.plutobooks.com Copyright © Mark P. Whitaker 2007 The right of Mark P. Whitaker to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Hardback ISBN-10 0 7453 2354 5 ISBN-13 978 0 7453 2354 1 Paperback ISBN-10 0 7453 2353 7 ISBN-13 978 0 7453 2353 4 Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data applied for 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Designed and produced for Pluto Press by Chase Publishing Services Ltd, Fortescue, Sidmouth, EX10 9QG, England Typeset from disk by Stanford DTP Services, Northampton, England Printed and bound in the European Union by Antony Rowe Ltd, Chippenham and Eastbourne, England Whitaker 00 PLUTO pre iv 14/11/06 08:40:31 CONTENTS Acknowledgements vi Note on Transliteration, Translation, Names, and Neutrality ix Three Prologues xi 1. Introduction: Why an Intellectual Biography of Sivaram Dharmeratnam? 1 2. Learning Politics from Sivaram 18 3. The Family Elephant 32 4. Ananthan and the Readers’ Circle 52 5. From SR to Taraki – A ‘Serious Unserious’ Journey 79 6. -

Dry Zone Urban Water and Sanitation Project – Additional Financing (RRP SRI 37381)

Dry Zone Urban Water and Sanitation Project – Additional Financing (RRP SRI 37381) DEVELOPMENT COORDINATION A. Major Development Partners: Strategic Foci and Key Activities 1. In recent years, the Asian Development Bank (ADB) and the Government of Japan have been the major development partners in water supply. Overall, several bilateral development partners are involved in this sector, including (i) Japan (providing support for Kandy, Colombo, towns north of Colombo, and Eastern Province), (ii) Australia (Ampara), (iii) Denmark (Colombo, Kandy, and Nuwaraeliya), (iv) France (Trincomalee), (v) Belgium (Kolonna–Balangoda), (vi) the United States of America (Badulla and Haliela), and (vii) the Republic of Korea (Hambantota). Details of projects assisted by development partners are in the table below. The World Bank completed a major community water supply and sanitation project in 2010. Details of Projects in Sri Lanka Assisted by the Development Partners, 2003 to Present Development Amount Partner Project Name Duration ($ million) Asian Development Jaffna–Killinochchi Water Supply and Sanitation 2011–2016 164 Bank Dry Zone Water Supply and Sanitation 2009–2014 113 Secondary Towns and Rural Community-Based 259 Water Supply and Sanitation 2003–2014 Greater Colombo Wastewater Management Project 2009–2015 100 Danish International Kelani Right Bank Water Treatment Plant 2008–2010 80 Development Agency Nuwaraeliya District Group Water Supply 2006–2010 45 Towns South of Kandy Water Supply 2005–2010 96 Government of Eastern Coastal Towns of Ampara -

Sri Lanka –Eastern Province – Trincomalee – Security Situation – Human Rights – Military and Paramilitary Groups – TMVP – Tamils with LTTE Links – Kiliveddy - Muthur

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: LKA35265 Country: Sri Lanka Date: 5 August 2009 Keywords: – Sri Lanka –Eastern Province – Trincomalee – Security situation – Human Rights – Military and paramilitary groups – TMVP – Tamils with LTTE Links – Kiliveddy - Muthur This response was prepared by the Research & Information Services Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. This research response may not, under any circumstance, be cited in a decision or any other document. Anyone wishing to use this information may only cite the primary source material contained herein. Questions 1. Please provide an update of the security situation in the East of Sri Lanka, particularly Trincomalee. 2. Is there a large military presence in Trincomalee? Are there reports of human rights abuses by the military in the east? 3. Do paramilitary groups/pro-government militias (such as those previously headed by Karuna and/or Pilliyan) still operate in Trincomalee? Are they still a threat to Tamils who are suspected of having LTTE links? 4. Is there any evidence of a town called Kiliveddy Muthur Trincomalee? Prior to the Sri Lankan government claiming victory over the LTTE, was Kiliveddy controlled by the LTTE or the government? RESPONSE 1. Please provide an update of the security situation in the East of Sri Lanka, particularly Trincomalee. The response to this question has been divided into two sections, the first dealing specifically with security in Trincomalee and the second relating more generally to the security situation in the Eastern Province of Sri Lanka.