Article Full Text

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Many-Storied Place

A Many-storied Place Historic Resource Study Arkansas Post National Memorial, Arkansas Theodore Catton Principal Investigator Midwest Region National Park Service Omaha, Nebraska 2017 A Many-Storied Place Historic Resource Study Arkansas Post National Memorial, Arkansas Theodore Catton Principal Investigator 2017 Recommended: {){ Superintendent, Arkansas Post AihV'j Concurred: Associate Regional Director, Cultural Resources, Midwest Region Date Approved: Date Remove not the ancient landmark which thy fathers have set. Proverbs 22:28 Words spoken by Regional Director Elbert Cox Arkansas Post National Memorial dedication June 23, 1964 Table of Contents List of Figures vii Introduction 1 1 – Geography and the River 4 2 – The Site in Antiquity and Quapaw Ethnogenesis 38 3 – A French and Spanish Outpost in Colonial America 72 4 – Osotouy and the Changing Native World 115 5 – Arkansas Post from the Louisiana Purchase to the Trail of Tears 141 6 – The River Port from Arkansas Statehood to the Civil War 179 7 – The Village and Environs from Reconstruction to Recent Times 209 Conclusion 237 Appendices 241 1 – Cultural Resource Base Map: Eight exhibits from the Memorial Unit CLR (a) Pre-1673 / Pre-Contact Period Contributing Features (b) 1673-1803 / Colonial and Revolutionary Period Contributing Features (c) 1804-1855 / Settlement and Early Statehood Period Contributing Features (d) 1856-1865 / Civil War Period Contributing Features (e) 1866-1928 / Late 19th and Early 20th Century Period Contributing Features (f) 1929-1963 / Early 20th Century Period -

William Adams and Tokugawa Ieyasu!

Realize a NHK drama centered on William Adams and Tokugawa Ieyasu! We request for your support and cooperation with our Petition Campaign! Recognized in Japan by the name, Miura Anjin, this English sailor became the diplomatic advisor to Tokugawa Ieyasu, and greatly contributed to the development of Japan with his profound knowledge of navigation and shipbuilding. Four cities connected to Adams: Usuki of Oita prefecture, Ito of Shizuoka prefecture, Yokosuka of Kanagawa prefecture, and Hirado of Nagasaki prefecture, have formed the “ANJIN Project Committee,” and are working together to honor Adams achievements, and also propose a theme based on William Adams and Tokugawa Ieyasu for Taiga Drama. Taiga Drama is a renowned historical drama series created by NHK, Japan’s sole public broadcasting organization. Themes for this annual drama are selected from Japan’s rich history. To further increase the chances of our Taiga Drama proposal to NHK, we have started a Petition Campaign! To sign the petition, please fill your name and address on the form below: Petition Form I support the creation of a NHK Taiga Drama based around the theme of William Adams and Tokugawa Ieyasu. Address Name Prefecture* Municipality* Land number is e.g. Taro Yokosuka Kanagawa Ogawa-cho, Yokosuka not required. e.g. William Adams U.K. Medway 1 2 按針メモリアルパーク 3 4 5 三浦按針上陸記念公園 6 7 三浦按針之墓 8 9 会社名 10 *Those overseas should write your Country in “Prefecture” (e.g. U.K.) and your City in “Municipality” (e.g. Medway). ・Please submit the completed form to the division below (bring the form directly or send it by mail or FAX). -

Alaska OCS Socioeconomic Studies Program

Technical Report Number 36 Alaska OCS Socioeconomic Studies Program Sponsor: Bureau of Land Management Alaska Outer Northern Gulf of Alaska Petroleum Development Scenarios Sociocultural Impacts The United States Department of the Interior was designated by the Outer Continental Shelf (OCS) Lands Act of 1953 to carry out the majority of the Act’s provisions for administering the mineral leasing and develop- ment of offshore areas of the United States under federal jurisdiction. Within the Department, the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) has the responsibility to meet requirements of the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 (NEPA) as well as other legislation and regulations dealing with the effects of offshore development. In Alaska, unique cultural differences and climatic conditions create a need for developing addi- tional socioeconomic and environmental information to improve OCS deci- sion making at all governmental levels. In fulfillment of its federal responsibilities and with an awareness of these additional information needs, the BLM has initiated several investigative programs, one of which is the Alaska OCS Socioeconomic Studies Program (SESP). The Alaska OCS Socioeconomic Studies Program is a multi-year research effort which attempts to predict and evaluate the effects of Alaska OCS Petroleum Development upon the physical, social, and economic environ- ments within the state. The overall methodology is divided into three broad research components. The first component identifies an alterna- tive set of assumptions regarding the location, the nature, and the timing of future petroleum events and related activities. In this component, the program takes into account the particular needs of the petroleum industry and projects the human, technological, economic, and environmental offshore and onshore development requirements of the regional petroleum industry. -

Aleuts: an Outline of the Ethnic History

i Aleuts: An Outline of the Ethnic History Roza G. Lyapunova Translated by Richard L. Bland ii As the nation’s principal conservation agency, the Department of the Interior has re- sponsibility for most of our nationally owned public lands and natural and cultural resources. This includes fostering the wisest use of our land and water resources, protecting our fish and wildlife, preserving the environmental and cultural values of our national parks and historical places, and providing for enjoyment of life through outdoor recreation. The Shared Beringian Heritage Program at the National Park Service is an international program that rec- ognizes and celebrates the natural resources and cultural heritage shared by the United States and Russia on both sides of the Bering Strait. The program seeks local, national, and international participation in the preservation and understanding of natural resources and protected lands and works to sustain and protect the cultural traditions and subsistence lifestyle of the Native peoples of the Beringia region. Aleuts: An Outline of the Ethnic History Author: Roza G. Lyapunova English translation by Richard L. Bland 2017 ISBN-13: 978-0-9965837-1-8 This book’s publication and translations were funded by the National Park Service, Shared Beringian Heritage Program. The book is provided without charge by the National Park Service. To order additional copies, please contact the Shared Beringian Heritage Program ([email protected]). National Park Service Shared Beringian Heritage Program © The Russian text of Aleuts: An Outline of the Ethnic History by Roza G. Lyapunova (Leningrad: Izdatel’stvo “Nauka” leningradskoe otdelenie, 1987), was translated into English by Richard L. -

A Biomolecular Anthropological Investigation of William Adams, The

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN A biomolecular anthropological investigation of William Adams, the frst SAMURAI from England Fuzuki Mizuno1*, Koji Ishiya2,3, Masami Matsushita4, Takayuki Matsushita4, Katherine Hampson5, Michiko Hayashi1, Fuyuki Tokanai6, Kunihiko Kurosaki1* & Shintaroh Ueda1,5 William Adams (Miura Anjin) was an English navigator who sailed with a Dutch trading feet to the far East and landed in Japan in 1600. He became a vassal under the Shogun, Tokugawa Ieyasu, was bestowed with a title, lands and swords, and became the frst SAMURAI from England. "Miura" comes from the name of the territory given to him and "Anjin" means "pilot". He lived out the rest of his life in Japan and died in Hirado, Nagasaki Prefecture, in 1620, where he was reportedly laid to rest. Shortly after his death, graveyards designated for foreigners were destroyed during a period of Christian repression, but Miura Anjin’s bones were supposedly taken, protected, and reburied. Archaeological investigations in 1931 uncovered human skeletal remains and it was proposed that they were those of Miura Anjin. However, this could not be confrmed from the evidence at the time and the remains were reburied. In 2017, excavations found skeletal remains matching the description of those reinterred in 1931. We analyzed these remains from various aspects, including genetic background, dietary habits, and burial style, utilizing modern scientifc techniques to investigate whether they do indeed belong to the frst English SAMURAI. William Adams was born in Gillingham, England in 1564. He worked in a shipyard from the age of 12, and later studied shipbuilding techniques, astronomy and navigation. -

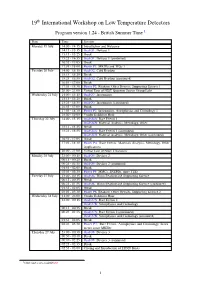

19 International Workshop on Low Temperature Detectors

19th International Workshop on Low Temperature Detectors Program version 1.24 - British Summer Time 1 Date Time Session Monday 19 July 14:00 - 14:15 Introduction and Welcome 14:15 - 15:15 Oral O1: Devices 1 15:15 - 15:25 Break 15:25 - 16:55 Oral O1: Devices 1 (continued) 16:55 - 17:05 Break 17:05 - 18:00 Poster P1: MKIDs and TESs 1 Tuesday 20 July 14:00 - 15:15 Oral O2: Cold Readout 15:15 - 15:25 Break 15:25 - 16:55 Oral O2: Cold Readout (continued) 16:55 - 17:05 Break 17:05 - 18:30 Poster P2: Readout, Other Devices, Supporting Science 1 20:00 - 21:00 Virtual Tour of NIST Quantum Sensor Group Labs Wednesday 21 July 14:00 - 15:15 Oral O3: Instruments 15:15 - 15:25 Break 15:25 - 16:55 Oral O3: Instruments (continued) 16:55 - 17:05 Break 17:05 - 18:30 Poster P3: Instruments, Astrophysics and Cosmology 1 18:00 - 19:00 Vendor Exhibitor Hour Thursday 22 July 14:00 - 15:15 Oral O4A: Rare Events 1 Oral O4B: Material Analysis, Metrology, Other 15:15 - 15:25 Break 15:25 - 16:55 Oral O4A: Rare Events 1 (continued) Oral O4B: Material Analysis, Metrology, Other (continued) 16:55 - 17:05 Break 17:05 - 18:30 Poster P4: Rare Events, Materials Analysis, Metrology, Other Applications 20:00 - 21:00 Virtual Tour of NIST Cleanoom Monday 26 July 23:00 - 00:15 Oral O5: Devices 2 00:15 - 00:25 Break 00:25 - 01:55 Oral O5: Devices 2 (continued) 01:55 - 02:05 Break 02:05 - 03:30 Poster P5: MMCs, SNSPDs, more TESs Tuesday 27 July 23:00 - 00:15 Oral O6: Warm Readout and Supporting Science 00:15 - 00:25 Break 00:25 - 01:55 Oral O6: Warm Readout and Supporting Science -

The Discovery of the Sea

The Discovery of the Sea "This On© YSYY-60U-YR3N The Discovery ofthe Sea J. H. PARRY UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS Berkeley • Los Angeles • London Copyrighted material University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles University of California Press, Ltd. London, England Copyright 1974, 1981 by J. H. Parry All rights reserved First California Edition 1981 Published by arrangement with The Dial Press ISBN 0-520-04236-0 cloth 0-520-04237-9 paper Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 81-51174 Printed in the United States of America 123456789 Copytightad material ^gSS3S38SSSSSSSSSS8SSgS8SSSSSS8SSSSSS©SSSSSSSSSSSSS8SSg CONTENTS PREFACE ix INTROn ilCTION : ONE S F A xi PART J: PRE PARATION I A RELIABLE SHIP 3 U FIND TNG THE WAY AT SEA 24 III THE OCEANS OF THE WORI.n TN ROOKS 42 ]Jl THE TIES OF TRADE 63 V THE STREET CORNER OF EUROPE 80 VI WEST AFRICA AND THE ISI ANDS 95 VII THE WAY TO INDIA 1 17 PART JJ: ACHJF.VKMKNT VIII TECHNICAL PROBL EMS AND SOMITTONS 1 39 IX THE INDIAN OCEAN C R O S S T N C. 164 X THE ATLANTIC C R O S S T N C 1 84 XJ A NEW WORT D? 20C) XII THE PACIFIC CROSSING AND THE WORI.n ENCOMPASSED 234 EPILOC.IJE 261 BIBLIOGRAPHIC AI. NOTE 26.^ INDEX 269 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS 1 An Arab bagMa from Oman, from a model in the Science Museum. 9 s World map, engraved, from Ptolemy, Geographic, Rome, 1478. 61 3 World map, woodcut, by Henricus Martellus, c. 1490, from Imularium^ in the British Museum. -

The Japanese Samurai Code: Classic Strategies for Success Kindle

THE JAPANESE SAMURAI CODE: CLASSIC STRATEGIES FOR SUCCESS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Boye Lafayette De Mente | 192 pages | 01 Jun 2005 | Tuttle Publishing | 9780804836524 | English | Boston, United States The Japanese Samurai Code: Classic Strategies for Success PDF Book Patrick Mehr on May 4, pm. The culture and tradition of Japan, so different from that of Europe, never ceases to enchant and intrigue people from the West. Hideyoshi was made daimyo of part of Omi Province now Shiga Prefecture after he helped take the region from the Azai Clan, and in , Nobunaga sent him to Himeji Castle to face the Mori Clan and conquer western Japan. It is an idea taken from Confucianism. Ieyasu was too late to take revenge on Akechi Mitsuhide for his betrayal of Nobunaga—Hideyoshi beat him to it. Son of a common foot soldier in Owari Province now western Aichi Prefecture , he joined the Oda Clan as a foot soldier himself in After Imagawa leader Yoshimoto was killed in a surprise attack by Nobunaga, Ieyasu decided to switch sides and joined the Oda. See our price match guarantee. He built up his capital at Edo now Tokyo in the lands he had won from the Hojo, thus beginning the Edo Period of Japanese history. It emphasised loyalty, modesty, war skills and honour. About this item. Installing Yoshiaki as the new shogun, Nobunaga hoped to use him as a puppet leader. Whether this was out of disrespect for a "beast," as Mitsuhide put it, or cover for an act of mercy remains a matter of debate. While Miyamoto Musashi may be the best-known "samurai" internationally, Oda Nobunaga claims the most respect within Japan. -

HERMIONE N March 10, 1780, the Marquis De Lafayette Boarded Ohermione on His Way to the Coasts of North America

HERMIONE n March 10, 1780, The Marquis de Lafayette boarded OHermione on his way to the coasts of North America. Frigate of the American War He left to announce the arrival of royal troops to fi ght of Independence the English occupier on the side of the insurgents. The 1779 - 1793 crossing was accomplished in the record time of 48 days. A 1/48 SCALE MONOGRAPH This performance was due to Hermione’s excellent nautical qualities. In fact, Hermione was a new-generation frigate The book includes all timbering plans built before the revolution. Started on the ways in December Jean-Claude Lemineur 1778, she benefi ted from important advances that were Patrick Villiers brought about by a new concept developed during the second half of the 18th century that translated into seagoing capabilities well beyond those of vessels built according to older designs. Like the other frigates of her generation she allied speed and fi repower, allowing her to rival those of the Royal Navy. But what did Hermione look like? Surprisingly, nothing specifi c remains concerning her, except for the information that she was constructed on the same plans as Concorde, built in 1777. As it turns out, Concorde’s lines were taken off by the Royal Navy after her capture in 1783, and the plans were kept at the NMM in Greenwich. It is fair to believe that Hermione is similar. However, the plans reveal some peculiarities specifi c to Concorde, which is and not present on Hermione. Her battery is pierced for 14 gunports to each side, not counting the chase ports. -

The Grammar of English Grammars, 2 Chapter Iv

1 CHAPTER I. CHAPTER II. CHAPTER III. CHAPTER X. CHAPTER XI. CHAPTER I. CHAPTER II. CHAPTER III. CHAPTER IV. CHAPTER V. CHAPTER VI. CHAPTER I. CHAPTER II. CHAPTER III. CHAPTER IV. CHAPTER V. CHAPTER VIII. CHAPTER I CHAPTER II CHAPTER III. CHAPTER IV. CHAPTER V. CHAPTER VI. CHAPTER I. CHAPTER II. CHAPTER III. CHAPTER IV. CHAPTER I. CHAPTER II. CHAPTER III. THE GRAMMAR OF ENGLISH GRAMMARS, 2 CHAPTER IV. CHAPTER V. CHAPTER VI. CHAPTER VII. CHAPTER VIII. CHAPTER IX. CHAPTER X. CHAPTER XI. CHAPTER I. CHAPTER II. CHAPTER III. CHAPTER IV. CHAPTER V. CHAPTER VI. THE GRAMMAR OF ENGLISH GRAMMARS, WITH AN INTRODUCTION HISTORICAL AND CRITICAL; THE WHOLE METHODICALLY ARRANGED AND AMPLY ILLUSTRATED; WITH FORMS OF CORRECTING AND OF PARSING, IMPROPRIETIES FOR CORRECTION, EXAMPLES FOR PARSING, QUESTIONS FOR EXAMINATION, EXERCISES FOR WRITING, OBSERVATIONS FOR THE ADVANCED STUDENT, DECISIONS AND PROOFS FOR THE SETTLEMENT OF DISPUTED POINTS, OCCASIONAL STRICTURES AND DEFENCES, AN EXHIBITION OF THE SEVERAL METHODS OF ANALYSIS, AND A KEY TO THE ORAL EXERCISES: TO WHICH ARE ADDED FOUR APPENDIXES, PERTAINING SEPARATELY TO THE FOUR PARTS OF GRAMMAR. BY GOOLD BROWN, THE GRAMMAR OF ENGLISH GRAMMARS, 3 AUTHOR OF THE INSTITUTES OF ENGLISH GRAMMAR, THE FIRST LINES OF ENGLISH GRAMMAR, ETC. "So let great authors have their due, that Time, who is the author of authors, be not deprived of his due, which is, farther and farther to discover truth."--LORD BACON. SIXTH EDITION--REVISED AND IMPROVED. ENLARGED BY THE ADDITION OF A COPIOUS INDEX OF MATTERS. BY SAMUEL U. BERRIAN, -

Oda Nobunaga in Japanese Videogames the Case of Nobunaga’S Ambition: Sphere of Influence (Koei, 2013)

Trabajo Fin de Máster Oda Nobunaga en los videojuegos japoneses El caso de Nobunaga’s Ambition: Sphere of Influence (Koei, 2013) Oda Nobunaga in Japanese videogames The case of Nobunaga’s Ambition: Sphere of Influence (Koei, 2013) Autora Claudia Bonillo Fernández Directoras Elena Barlés Báguena Amparo Martínez Herranz Facultad de Filosofía y Letras/ Departamento de Historia del Arte Curso 2017-2018 2 ÍNDICE I. PRESENTACIÓN DEL TRABAJO .......................................................................................................................... 3 1. Delimitación del tema y causas de su elección ..................................................................................................... 3 2. Estado de la cuestión ............................................................................................................................................. 5 3. Objetivos del trabajo ............................................................................................................................................. 9 4. Metodología .......................................................................................................................................................... 9 4.1. Búsqueda, recopilación, lectura y análisis de material bibliográfico ........................................................... 10 4.2. Búsqueda, recopilación, lectura y análisis de material documental ............................................................. 11 4.3. Trabajo de campo ........................................................................................................................................ -

Redalyc.Tokugawa Ieyasu and the Christian Daimyó During the Crisis

Bulletin of Portuguese - Japanese Studies ISSN: 0874-8438 [email protected] Universidade Nova de Lisboa Portugal Costa Oliveira e, João Paulo Tokugawa Ieyasu and the Christian Daimyó during the Crisis Of 1600 Bulletin of Portuguese - Japanese Studies, núm. 7, december, 2003, pp. 45-71 Universidade Nova de Lisboa Lisboa, Portugal Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=36100703 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative BPJS, 2003, 7, 45-71 TOKUGAWA IEYASU AND THE CHRISTIAN DAIMYÓ DURING THE CRISIS OF 1600 1 João Paulo Oliveira e Costa Centro de História de Além-Mar, New University of Lisbon The process of the political reunification of the Japanese Empire 2 underwent its last great crisis in the period between the death of Toyotomi Hideyoshi 豊臣秀吉 (1536-1598),3 in September 1598, and the Battle of Seki- gahara, in October 1600. The entire process was at risk of being aborted, which could have resulted in the country lapsing back into the state of civil war and anarchy in which it had lived for more than a century.4 However, an individual by the name of Tokugawa Ieyasu 徳川家康 (1543-1616) 5 shrewdly took advantage of the hesitation shown by many of his rivals and the military weakness or lack of strategic vision on the part of others to take control of the Japanese Empire, which would remain in the hands of his family for more than 250 years.