Shared Burdens: the General Average Adjustment of the Jan Maria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Admiralty, Maritime & Naval

30 ANTIQUARIAN TITLES ON ADMIRALTY, MARITIME & NAVAL LAW May 10, 2016 The Lawbook Exchange, Ltd. (800) 422-6686 or (732) 382-1800 | Fax: (732) 382-1887 [email protected] | www.lawbookexchange.com 30 Antiquarian Titles on Admiralty, Maritime and Naval Law Scarce Eighteenth-Century Treatise on Prize Law and Privateering 1. Abreu y Bertodano, Felix Joseph de [c.1700-1775]. Traite Juridico-Politique sur les Prises Maritimes, et Sur les Moyens qui Doivent Concourir pour Rendre ces Prises Legitimes. Paris: Chez la Veuve Delaguette, 1758. Two volumes in one, each with title page and individual pagination. Octavo (6-1/2" x 4"). Contemporary speckled sheep, raised bands, lettering piece and gilt ornaments to spine, speckled edges, patterned endpapers. Some wear to corners, joints starting, some worming to lettering piece, joints and hinges. Attractive woodcut head-pieces. Toning to sections of text, light foxing to a few leaves, internally clean. An appealing copy of a scarce title. $1,500. * Second French edition. First published in Madrid in 1746, this treatise on prize law and privateering went through three other editions, all in France in a translation by the author, in 1753, 1758 and 1802. Little is known about Abreu, a minor Spanish noble and diplomat. According to the title page, he was a "membre de l'Academie Espagnole, & actuellement Envoye Extraordinaire de S.M. Catholique aupres du Roi de la Grande-Bretagne." All editions are scarce. OCLC locates 5 copies of all editions in the Americas, 1 of this edition (at Columbia University Law Library). Not in the British Museum Catalogue. -

A Comparative History of Insurance Law in Europe. a Research Agenda

Comparative Studies in the History of Insurance Law Studien zur vergleichenden Geschichte des Versicherungsrechts Volume / Band 1 A Comparative History of Insurance Law in Europe A Research Agenda Edited by Phillip Hellwege Duncker & Humblot · Berlin PHILLIP HELLWEGE (ED.) A Comparative History of Insurance Law in Europe Comparative Studies in the History of Insurance Law Studien zur vergleichenden Geschichte des Versicherungsrechts Edited by / Herausgegeben von Prof. Dr. Phillip Hellwege Volume / Band 1 A Comparative History of Insurance Law in Europe A Research Agenda Edited by Phillip Hellwege Duncker & Humblot · Berlin The project ‘A Comparative History of Insurance Law in Europe’ has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement No. 647019). Bibliographic information of the German national library The German national library registers this publication in the German national bibliography; specified bibliographic data are retrievable on the Internet about http://dnb.d-nb.de. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, translated, or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, without the expressed written consent of the publisher. © 2018 Duncker & Humblot GmbH, Berlin Printing: CPI buchbücher.de GmbH, Birkach Printed in Germany ISSN 2625-638X (Print) / ISSN 2625-6398 (Online) ISBN 978-3-428-15499-9 (Print) ISBN 978-3-428-55499-7 (E-Book) ISBN 978-3-428-85499-8 (Print & E-Book) Printed on no aging resistant (non-acid) paper according to ISO 9706 Internet: http://www.duncker-humblot.de Preface The history of insurance law has fallen into neglect, and the state of research is for a number of reasons unsatisfactory. -

Principles of Insurance Law Peter N

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Law Faculty Publications School of Law 2011 Principles of Insurance Law Peter N. Swisher University of Richmond, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/law-faculty-publications Part of the Insurance Law Commons Recommended Citation Jeffrey W. Stempel et al., Principles of Insurance Law (4th ed., 2011). This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PRINCIPLES OF INSURANCE LAW FOURTH EDITION JEFFREY W. STEMPEL Doris S. & Theodore B. Lee Professor of Law William S. Boyd School of Law University of Nevada, Las Vegas PETER N. SWISHER Professor of Law T.C. Williams School of Law University of Richmond ERIK S. KNUTSEN Associate Professor Queen's University Faculty of Law Kingston, Ontario, Canada • . LexisNexis· Preface There have been a number of important developments in liability insurance, property insurance, and life and health insurance that have significantly impacted insurance law. Accordingly, our Fourth Edition of Principles of Insurance Law has been substantially revised and updated in order to offer the insurance law student and practitioner a broad perspective of both traditional insurance law concepts and cutting-edge legal issues affecting contemporary insurance law theory and practice. We have retained .the organization substantially begun in the Third Edition, with fifteen chapters, a division that enables an expanded scope of topical coverage and also segments the law of insurance in a manner more amenable to study, as well as facilitating recombination and reordering of the chapters as desired by individual instructors. -

Taxation of Insurance Companies

Taxation of Insurance Companies Informational Paper 10 Wisconsin Legislative Fiscal Bureau January, 2017 Taxation of Insurance Companies Prepared by Sean Moran Wisconsin Legislative Fiscal Bureau One East Main, Suite 301 Madison, WI 53703 http://legis.wisconsin.gov/lfb Taxation of Insurance Companies This paper provides background information example, under a pure "term" life insurance on the taxation of insurance companies in policy, the insured pays a premium which Wisconsin. While the main topic is the separate obligates the insurance company to pay a specific state premiums tax imposed on certain insurance sum in the event of the insured's death during the companies, the imposition of the state corporate term of the policy. Term insurance is the most income/franchise tax is also discussed. straightforward type of life insurance policy in that the premium provides coverage only in the In order to put the taxation of insurance com- event of death during the policy's specified term. panies in focus, information is provided on the characteristics of the insurance industry and the Certain life insurance policies perform a bank- Wisconsin operations of some of the major com- like function in that policyholder premiums are panies in different lines of insurance. The regula- invested by the insurer on behalf of the insured. tory role of the Office of the Commissioner of Income from such investments is credited to the Insurance (OCI) is also discussed briefly. Finally, policyholder's account in determining the policy's a discussion of the rationale and issues of insur- "cash surrender value," which is the amount which ance taxation is presented and the insurance tax the insured would receive if he or she cancels the provisions of other states are outlined. -

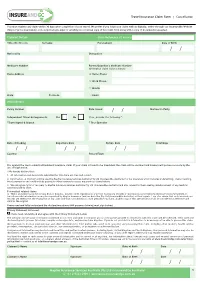

Cancellation Claim Form

Travel Insurance Claim Form | Cancellation You must register any claim within 30 days after completion of your travel. We prefer if you lodge your claim with us digitally, either through our InsureandGo Website (https://quote.insureandgo.com.au/policylogin.aspx) or emailing us a scanned copy of this claim form along with a copy of documents requested. Claimant Details Claim Reference (if known) Title (Mr/Mrs etc) Surname Forename(s) Date of Birth / / Nationality Occupation Medicare Number Parent/Guardian’s Medicare Number (If medical claim is for a minor) Home Address ' Home Phone ' Work Phone ' Mobile State Postcode Email Policy Details Policy Number Date Issued / / Number in Party Independent Travel Arrangements: Yes No If no, provide the following *: *Travel Agent & Branch * Tour Operator Date of Booking Departure Date Return Date Total Days / / / / / / Country Resort/Town It is against the law to submit a fraudulent insurance claim. If your claim is found to be fraudulent the claim will be declined and Insurers will pursue recovery by the use of legal action. I/We hereby declare that: 1. All information and documents submitted for this claim are true and correct. 2. Information on this form will be used by Mapfre Insurance Services Australia Pty Ltd (InsureandGo Australia) for my insurance which includes underwriting, claims handling, fraud prevention and could include passing to other insurers to access my previous claims history. 3. We subrogate rights of recovery to Mapfre Insurance Services Australia Pty Ltd (InsureandGo Australia) and also consent to them seeking reimbursement of any medical expenses paid by them. For medical related claims: 4. -

Introduction to Insurance

Introduction To Insurance By Cathy Pareto http://www.investopedia.com/university/insurance/default.asp Thanks very much for downloading the printable version of this tutorial. As always, we welcome any feedback or suggestions. http://www.investopedia.com/contact.aspx Table of Contents 1) Intro To Insurance: Introduction 2) Intro To Insurance: What Is Insurance? 3) Intro To Insurance: Fundamentals Of Insurance 4) Intro To Insurance: Property And Casualty Insurance 5) Intro To Insurance: Health Insurance 6) Intro To Insurance: Disability Insurance 7) Intro To Insurance: Long-Term Care Insurance 8) Intro To Insurance: Life Insurance 9) Intro To Insurance: Types Of Life Insurance 10) Intro To Insurance: Life Insurance Considerations 11) Intro To Insurance: Other Insurance Policies 12) Intro To Insurance: Conclusion Introduction In one form or another, we all own insurance. Whether it's auto, medical, liability, disability or life, insurance serves as an excellent risk-management and wealth- preservation tool. Having the right kind of insurance is a critical component of any good financial plan. While most of us own insurance, many of us don't understand what it is or how it works. In this tutorial, we'll review the basics of insurance and how it works, then take you through the main types of insurance out there. (To read more about insurance, see our Special Insurance Feature.) What Is Insurance? Insurance is a form of risk management in which the insured transfers the cost of potential loss to another entity in exchange for monetary compensation known as the premium. (For background reading, see The History Of Insurance In (Page 1 of 29) Copyright © 2010, Investopedia.com - All rights reserved. -

Travel Insurance Claim Form | Cruise Mapfre Insurance Services

Travel Insurance Claim Form | Cruise You must register any claim within 30 days after completion of your travel. We prefer if you lodge your claim with us digitally, either through our InsureandGo Website (https://quote.insureandgo.com.au/policylogin.aspx) or emailing us a scanned copy of this claim form along with a copy of documents requested. Claimant Details Claim Reference (if known) Title (Mr/Mrs etc) Surname Forename(s) Date of Birth / / Nationality Occupation Medicare Number Parent/Guardian’s Medicare Number (If medical claim is for a minor) Home Address ' Home Phone ' Work Phone ' Mobile State Postcode Email Policy Details Policy Number Date Issued / / Number in Party Independent Travel Arrangements: Yes No If no, provide the following *: *Travel Agent & Branch * Tour Operator Date of Booking Departure Date Return Date Total Days / / / / / / Country Resort/Town It is against the law to submit a fraudulent insurance claim. If your claim is found to be fraudulent the claim will be declined and Insurers will pursue recovery by the use of legal action. I/We hereby declare that: 1. All information and documents submitted for this claim are true and correct. 2. Information on this form will be used by Mapfre Insurance Services Australia Pty Ltd (InsureandGo Australia) for my insurance which includes underwriting, claims handling, fraud prevention and could include passing to other insurers to access my previous claims history. 3. We subrogate rights of recovery to Mapfre Insurance Services Australia Pty Ltd (InsureandGo Australia) and also consent to them seeking reimbursement of any medical expenses paid by them. For medical related claims: 4. -

Determinants of Bancassurance Demand and Life

UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES SCHOOL OF BANKING AND FINANCE INTERNATIONAL FINANCIAL SERVICES: Determinants of Bancassurance Demand and Life Insurance Consumption CSABA SZABOLCS JOSA This thesis is submitted in fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Commerce (Honours) at the University of New South Wales. 2005 CERTIFICATION I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and to the best of my knowledge it contains no materials previously published or written by another person, or substantial proportions of material which have been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma at UNSW or any other educational institution, except where due acknowledgement is made in the thesis. Any contribution made to the research by others, with whom I have worked at UNSW or elsewhere, is explicitly acknowledged in the thesis. I also declare that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work, except to the extent that assistance from others in the project’s design and conception or in style, presentation and linguistic expression is acknowledged. Csaba Josa 2005 ii ABSTRACT This thesis is a pioneer study that examines the growing importance of global insurance markets and the factors that determine continued success and viability. A couple of issues relating to risk and insurance that have not been examined to such an extent in previous studies are represented through the examination of two of the fastest growing areas within international insurance services, namely those of global bancassurance and life insurance markets. Firstly, this thesis establishes what determines the demand for bancassurance using a sample of 73 companies from 28 developed and developing countries from across the globe. -

Maritime Risk Management. Essays on the History of Marine Insurance

Comparative Studies in the History of Insurance Law Studien zur vergleichenden Geschichte des Versicherungsrechts Volume / Band 11 Maritime Risk Management Essays on the History of Marine Insurance, General Average and Sea Loan Edited by Phillip Hellwege and Guido Rossi Hellwege/Rossi (Eds.) (Eds.) Hellwege/Rossi Maritime Risk Management · · HIL 11 Duncker & Humblot · Berlin https://doi.org/10.3790/978-3-428-58260-0 Generated at 93.143.148.71 on 2021-05-03, 14:56:56 UTC OPEN ACCESS PHILLIp HELLWEGE AND GUIDO ROSSi (EDS.) Maritime Risk Management https://doi.org/10.3790/978-3-428-58260-0 Generated at 93.143.148.71 on 2021-05-03, 14:56:56 UTC OPEN ACCESS Comparative Studies in the History of Insurance Law Studien zur vergleichenden Geschichte des Versicherungsrechts Edited by / Herausgegeben von Prof. Dr. Phillip Hellwege Volume / Band 11 https://doi.org/10.3790/978-3-428-58260-0 Generated at 93.143.148.71 on 2021-05-03, 14:56:56 UTC OPEN ACCESS Maritime Risk Management Essays on the History of Marine Insurance, General Average and Sea Loan Edited by Phillip Hellwege and Guido Rossi Duncker & Humblot · Berlin https://doi.org/10.3790/978-3-428-58260-0 Generated at 93.143.148.71 on 2021-05-03, 14:56:56 UTC OPEN ACCESS The project ‘A Comparative History of Insurance Law in Europe’ (grant agreement No. 647019) and the project ‘AveTransRisk. Average – Transaction Costs and Risk Management during the First Globalization (Sixteenth- Eighteenth Centuries)’ (grant agreement No. 724544) have received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme. -

The Breadth and Scope of the Global Reinsurance Market and the Critical

The Breadth and Scope of the Global Reinsurance Market and the Critical Role Such Market Plays in Supporting Insurance in the United States FEDERAL INSURANCE OFFICE, U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY Completed pursuant to Title V of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act DECEMBER 2014 The Breadth And Scope Of The Global Reinsurance Market And The Critical Role Such Market Plays In Supporting Insurance In The United States Table of Contents I. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................. 1 II. BRIEF HISTORY OF REINSURANCE ................................................................................ 3 III. DEFINITION AND FORMS OF REINSURANCE............................................................ 7 A. Reinsurance Defined ........................................................................................................ 7 B. Forms of Reinsurance....................................................................................................... 8 1. Treaty Reinsurance ....................................................................................................... 8 2. Facultative Reinsurance .............................................................................................. 10 IV. THE PURPOSE AND IMPORTANCE OF REINSURANCE ......................................... 11 A. Uses of Reinsurance ....................................................................................................... 11 1. Stabilizing -

A History of Insurance

A History of Insurance Table of Contents Introduction 2 Risk tradition and risk trading 4 From conjecture to calculation 6 The birth of modern insurance 8 Global expansion 14 Reinsurance 22 San Francisco 24 Swiss Re History 28 Money matters 36 World War II 42 Booming economy and growing problems 44 More money matters 48 A poor start for the 21st century 52 Natural catastrophes 54 Financial catastrophes, regulation, and a positive outlook 58 Introduction A total of USD 4 613 billion was spent globally on insurance in 2012. Modern life can hardly be imagined without this form of risk protection. And yet, comparatively little is known about the history of the industry, although it has played a major part in shaping today’s society and culture. Industrialisation, welfare, innovation, economic development, or modernisation per se would not have been the same without private insurance. Since the 18th century, building insurance on solidarity, business acumen, and the logic of calculation has proved an almost unbeatable business idea. It was to conquer the world over the next centuries. Trade and emigration became the two most important enablers for creating a global insurance safety network. As every history, that of insurance has been exposed to challenges. Many were inherent to the industry. Some large catastrophes proved too big to deal with for some companies. From the San Francisco Earthquake in 1906 to Hurricane Betsy in 1965 or the attack on the World Trade Center in 2001 the industry had to cope with unexpected enormous losses. But challenges also came from the economy and its recurring crises which at times caused bigger losses than the worst insured catastrophes. -

Marine Insurance in Britain and America, 1720-1844: a Comparative Institutional Analysis

Marine Insurance in Britain and America, 1720-1844: A Comparative Institutional Analysis Christopher Kingston ∗ August 21, 2005 Abstract This paper examines how the marine insurance industry evolved in Britain and America dur- ing its critical formative period, focusing on the information asymmetries and agency problems which were inherent to the technology of overseas trade at the time, and on the path-dependent manner in which the institutions which addressed these problems evolved. We argue that the market was characterized by multiple equilibria because of a potential adverse selection prob- lem. Exogenous shocks and endogenous institutional development combined to bring about a bifurcation of institutional structure, the effects of which persist to the present day. Introduction Marine insurance played a vital role in facilitating the expansion of trade during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, but the industry developed in different ways in different countries. By the mid nineteenth century, the British marine insurance market was dominated by Lloyd’s of London, a marketplace where private individuals risked their personal fortunes by insuring vessels and cargoes with unlimited liability. In contrast, in the United States, private underwriting had virtually ∗I am grateful to Daniel Barbezat, Ann Carlos, Douglass North, John Nye, Beth Yarbrough, George Zanjani, and seminar participants at Washington University in St. Louis, the University of Connecticut, the Economic History Society, the Risk Theory Society, the Business