Album (Note Original Album Spelling)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interview with Frisner Augustin—3/24/1982 East 96Th Street, East Flatbush, Brooklyn, New York

Interview with Frisner Augustin—3/24/1982 East 96th Street, East Flatbush, Brooklyn, New York Frisner’s Life in Haiti L: This is an interview with Frisner Augustin, Master Drummer from Haiti. First, I just want to get the facts—the day that you were born, where you were born… F: Okay, the day I born is one, three, forty-eight, right? So, I born in Port- au-Prince. But my mother born in Port-a-Prince, but my grandmother born in Jacmel. L: Is that your mother’s mother? F: My grandmother, yeah. But my father born in Port-au-Prince, but, you know, my father’s father born in Léogane. I come from two parent, you know, two pärent—parent or pärent, I don’t know. Because, you know, English is not my language. But in my country they speak Creole. But everybody try to speak French. You’re supposed to go to school to speak French. But my parent don’t have any money to push me very good in big school, and I try to learn by some friend. But, in Haiti, my father, you know, time I got to be about six years old, and my father left my mother, and, you know, my mother can’t help me to push me in school. Okay, I got all my parent, my uncle play drum and be travel lot. He go to St. Thomas, St. Croix, Puerto Rico, and New York and go back to Haiti, St. Vincent and go back to Haiti. And soon I grow up, I say, I want to learn how to play drum. -

Black Brooklyn Renaissance Digital Archive Sherif Sadek, Akhnaton Films

Black Brooklyn Renaissance (BBR) Digital Archive About the Digital Archive CONTENTS This digital archive contains 73 discs, formatted as playable DVDs for use in compatible DVD players and computers, and audio CDs where indicated. The BBR Digital Archive is organized according to performance genres: dance, music, visual art, spoken word, community festival/ritual arts, and community/arts organizations. Within each genre, performance events and artist interviews are separated. COPYRIGHT Black Brooklyn Renaissance: Black Arts + Culture (BBR) Digital Archive is copyright 2011, and is protected by U.S. Copyright Law, along with privacy and publicity rights. Users may access the recordings solely for individual and nonprofit educational and research purposes. Users may NOT make or distribute copies of the recordings or their contents, in whole or in part, for any purpose. If a user wishes to make any further use of the recordings, the user is responsible for obtaining the written permission of Brooklyn Arts Council (BAC) and/or holders of other rights. BAC assumes no responsibility for any error, omission, interruption, deletion, defect, delay in operation or transmission, or communications line failure, involving the BBR Digital Archive. BAC feels a strong ethical responsibility to the people who have consented to have their lives documented for the historical record. BAC asks that researchers approach the materials in BBR Digital Archive with respect for the sensibilities of the people whose lives, performances, and thoughts are documented here. By accessing the contents of BBR Digital Archive, you represent that you have read, understood, and agree to comply with the above terms and conditions of use of the BBR Digital Archive. -

Drummer, Give Me My Sound: Frisner Augustin

Fall–Winter 2012 Volume 38: 3–4 The Journal of New York Folklore Drummer, Give Me My Sound: Frisner Augustin Andy Statman, National Heritage Fellow Dude Ranch Days in Warren County, NY Saranac Lake Winter Carnival The Making of the Adirondack Folk School From the Director The Schoharie Creek, had stood since 1855 as the longest single- From the Editor which has its origins span covered wooden bridge in the world. near Windham, NY, The Schoharie’s waters then accelerated to In the spirit of full dis- feeds the Gilboa Res- the rate of flow of Niagara Falls as its path closure, I’m the one who ervoir in Southern narrowed, uprooting houses and trees, be- asked his mom to share Schoharie County. fore bursting onto the Mohawk River, just her Gingerbread Cookie Its waters provide west of Schenectady to flood Rotterdam recipe and Christmas drinking water for Junction and the historic Stockade section story as guest contribu- New York City, turn of Schenectady. tor for our new Food- the electricity-generating turbines at the A year later, in October 2012, Hurricane ways column. And, why not? It’s really not New York Power Authority, and are then Sandy hit the metropolitan New York that we couldn’t find someone else [be in loosed again to meander up the Schoharie area, causing widespread flooding, wind, touch, if you’re interested!]. Rather, I think Valley to Schoharie Crossing, the site of and storm damage. Clean up from this it’s good practice and quite humbling to an Erie Canal Aqueduct, where the waters storm is taking place throughout the entire turn the cultural investigator glass upon of the Schoharie Creek enter the Mohawk Northeast Corridor of the United States oneself from time to time, and to partici- River. -

Haitian Narrative the Personal Becomes National the National Becomes Personal

Haitian Narrative The Personal becomes National The National Becomes Personal Karen F. Dimanche Davis 4 November 2016 Hope College, Holland, Michigan HAITI – AYITI Florida, 600 miles Cuba, 70 miles Jamaica, 130 miles “Ayiti”--mountains L’UNION FAIT LA FORCE! This is also the national motto of the Republic of Benin, in West Africa, the homeland of most Haitians Jarre Trouée Roi Ghézo 1818 Wisdom Tales • Anancy, Bouki & Malice, Ti-Jean, and Br’er Rabbit • How to maintain morality yet survive life’s threats. • As Haitian stories/histories become national meta-myth, they encompass references to: – the revolutionary founding of the nation (1791-1804) • “L’union fait la force!” • Bois Caiman – rural community identity (the spirit of konbit) – service to the African lwas (spirits or energies) – US military & corporate imperialism – The Duvalier dictatorship’s state terrorism – deforestation, soil erosion, hurricanes, and flooding – mass exodus of farmers to city, Port- au-Prince – Le Tremblement, 2010 earthquake, Goudou-Goudou Danticat references Haitian values: • Konbit: Importance of family, group, community, not individuals • Importance of reputation and respect • Mountains beyond mountains (pa pi mal) • Thriving farm market economy (carrots, plantains, pigeon peas, calabash, cocoa, coffee • The importance of family stories, wisdom tales • Building sturdy, beautiful cement block houses • Local foods: snapper, sweet potatoes, salt cod, plantains, cassava bread • Natural herbal medications • Ingenuity to “out-fox” oppression (Trickster) • Pride in public appearance (neat, clean, pressed) Danticat references Haitian history: • Jean-Bertrand Aristide • Invasion/control by U.S. Marines 1915-1934, forced labor (re-ensavement) • Resistance by Cacos • Stories, murals, songs recall Petion, Dessalines, Toussaint, Charlemagne, etc. -

Brooklyn Rediscovers Cal Massey by Jeffrey Taylor

American Music Review Formerly the Institute for Studies in American Music Newsletter Th e H. Wiley Hitchcock Institute for Studies in American Music Conservatory of Music, Brooklyn College of the City University of New York Volume XXXIX, Number 2 Spring 2010 Brooklyn Rediscovers Cal Massey By Jeffrey Taylor With the gleaming towers of the Time Warner Center—Jazz at Lincoln Center’s home since 2004—gazing over midtown Manhattan, and thriving jazz programs at colleges and universities throughout the world fi rmly in place, it is sometimes diffi cult to remember when jazz did not play an unquestioned role in the musical academy. Yet it wasn’t until the early 1990s that jazz was well enough entrenched in higher education that scholars could begin looking back over the way the music was integrated into music curricula: Scott DeVeaux’s frequently quoted “Construct- ing the Jazz Tradition” from 1991 is a prime example.1 The past thirty years have seen an explosion of published jazz scholarship, with dozens of new books crowd- ing shelves (or websites) every year. The vast majority of these texts are devoted to the work of a single fi gure, with Duke Ellington and Louis Armstrong leading as popular subjects. But a few scholars, DeVeaux and Ingrid Monson among them, have noted the essential roles of musicians who worked primarily in the shadows, as composers, arrangers, accompanists, and sidepeople. Without these artists, whose contribution often goes completely unacknowledged in history books, jazz would have taken a very different path than the one we trace in our survey courses. -

National Heritage Fellowships

2020 NATIONAL HERITAGE FELLOWSHIPS NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR THE ARTS I 2020 NATIONAL HERITAGE FELLOWSHIPS Birchbark Canoe by Wayne Valliere Photo by Tim Frandy COVER: “One Pot Many Spoons” beadwork by Karen Ann Hoffman Photo by James Gill Photography CONTENTS MESSAGE FROM THE ACTING CHAIRMAN ...........................................................................................................................................................................................4 MESSAGE FROM THE DIRECTOR .............................................................................................................................................................................................................5 A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE NEA NATIONAL HERITAGE FELLOWSHIPS .........................................................................................................................................6 2020 NATIONAL HERITAGE FELLOWS William Bell .................................................................................................................................................................................8 Soul Singer and Songwriter > ATLANTA, GA Onnik Dinkjian ....................................................................................................................................................................... 10 Armenian Folk and Liturgical Singer > FORT LEE, NJ Zakarya and Naomi Diouf ............................................................................................................................................ -

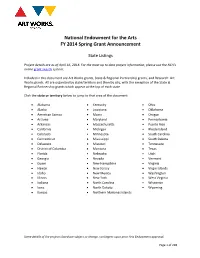

Spring 2014--All Grants Sorted by State

National Endowment for the Arts FY 2014 Spring Grant Announcement State Listings Project details are as of April 16, 2014. For the most up to date project information, please use the NEA's online grant search system. Included in this document are Art Works grants, State & Regional Partnership grants, and Research: Art Works grants. All are organized by state/territory and then by city, with the exception of the State & Regional Partnership grants which appear at the top of each state. Click the state or territory below to jump to that area of the document. • Alabama • Kentucky • Ohio • Alaska • Louisiana • Oklahoma • American Samoa • Maine • Oregon • Arizona • Maryland • Pennsylvania • Arkansas • Massachusetts • Puerto Rico • California • Michigan • Rhode Island • Colorado • Minnesota • South Carolina • Connecticut • Mississippi • South Dakota • Delaware • Missouri • Tennessee • District of Columbia • Montana • Texas • Florida • Nebraska • Utah • Georgia • Nevada • Vermont • Guam • New Hampshire • Virginia • Hawaii • New Jersey • Virgin Islands • Idaho • New Mexico • Washington • Illinois • New York • West Virginia • Indiana • North Carolina • Wisconsin • Iowa • North Dakota • Wyoming • Kansas • Northern Marianas Islands Some details of the projects listed are subject to change, contingent upon prior Arts Endowment approval. Page 1 of 228 Alabama Number of Grants: 5 Total Dollar Amount: $841,700 Alabama State Council on the Arts $741,700 Montgomery, AL FIELD/DISCIPLINE: State & Regional To support Partnership Agreement activities. Auburn University Main Campus $55,000 Auburn, AL FIELD/DISCIPLINE: Visual Arts To support the Alabama Prison Arts and Education Project. Through the Department of Human Development and Family Studies in the College of Human Sciences, the university will provide visual arts workshops taught by emerging and established artists for those who are currently incarcerated. -

Music in Haiti: an Annotated Bibliography and Research Guide

MUSIC IN HAITI: AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY AND RESEARCH GUIDE by William B. Stroud, B.A. A thesis submitted to the Graduate Council of Texas State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music with a Major in Music May 2015 Committee Members: Kevin Mooney, Chair Ludim Pedroza John Schmidt COPYRIGHT by William B. Stroud 2015 FAIR USE AND AUTHOR’S PERMISSION STATEMENT FAIR USE This work is protected by the Copyright Laws of the United States (Public Law 94-553, section 107). Consistent with fair use as defined in the Copyright Laws, brief quotations from this material are allowed with proper acknowledgement. Use of this material for financial gain without the author’s express written permission is not allowed. Duplication Permission As the copyright holder of this work I, William B. Stroud, refuse permission to copy in excess of the “Fair Use” exemption without my written permission. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Foremost, I would like to thank Dr. Kevin Mooney for his continued support throughout the thesis development and writing process. Without his guidance, none of this would have been possible. I would also like to thank the rest of my thesis committee: Dr. Ludim Pedroza and Dr. John Schmidt for their insight, dedication, and encouragement. My gratitude also extends to my parents, Bill and Judy Stroud, for their perseverance through what has been a non-linear collegiate trajectory. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .............................................................................................. -

Haiti, Singing for the Land, Sea, and Sky: Cultivating 45 (1-2): 112-135

45 (1-2): 112-135. Haiti, Singing for the Land, Sea, and Sky: Cultivating MUSICultures Ecological Metaphysics and Environmental Awareness through Music REBECCA DIRKSEN Abstract: Vodou drummer Jean-Michel Yamba echoes a refrain that has been reverberating through Haitian society for some time: the Earth is dangerously out of balance, and the world’s people are the cause. Scientific studies support this uneasy realization: the 2018 Global Climate Risk Index ranks Haiti as the single most vulnerable country to the effects of extreme weather events related to climate change. This article reflects on how humanity’s responsibility toward the environment has been deeply encoded as traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) within Vodou spiritual ecology, which is expressed through songs and interactions with the lwa (spirits). Résumé : Le percussionniste vodou Jean-Michel Yamba fait écho au refrain qui résonne depuis quelque temps dans la société haïtienne : la Terre est dangereusement en train de perdre son équilibre et c’est la population mondiale qui en est la cause. Les études scientifiques corroborent cette difficile prise de conscience : en 2018, le Global Climate Risk Index (Index des risques climatiques mondiaux), pointait Haïti en tant que pays le plus vulnérable aux effets des évènements météorologiques extrêmes liés aux changements climatiques. Cet article se penche sur la façon dont la responsabilité humaine envers l’environnement a été profondément encodée en tant que savoir écologique traditionnel au sein de l’écologie spirituelle du vodou, ce qui s’exprime à travers les chansons et les interactions avec les lwas (esprits). O Èzili malad o (x2) Nanpwen dlo nan syèl o Solèy boule tè o O Èzili malad o Nou pa gen chans mezanmi o1 This article has an accompanying video on our YouTube channel. -

SEM Annual Meeting, 2010, Los Angeles Weapons of Mass In- Struction

Volume 44 Number 3 May 2010 Metro Center, allowing access to pub- SEM Annual Meeting, lic transportation links throughout the Inside 2010, Los Angeles city (including Metro trains from the 1 SEM Annual Meeting, Los By Tara Browner, Chair, Local Ar- Los Angeles World Airport or Union Angeles rangements Committee Station to the meeting). A local area 1 Weapons of Mass Instruction small-bus transport system known 3 People and Places The Society for Ethnomusicology as DASH gives attendees the oppor- 6 nC2 will hold its 55th annual meeting in tunity to explore downtown LA with 9 BFE Annual Conference Los Angeles, November 11-14, 2010, ease, although quite a few attractions 11 Dan Sheehy named Director of with a pre-conference honoring of are within walking distance, includ- Center for Folklife and Cultural the life and work of Nazir Jaraizbhoy, ing the new Grammy Museum (three Heritage cosponsored by the UCLA Depart- blocks from the hotel), Nokia Theater, 11 Calls for Participation ment of Ethnomusicology and the Los Angeles Theater, and of course 13 Announcements SEM South Asia Performing Arts Walt Disney Concert Hall. Further 14 Conferences Calendar sub-group, on November 10. The afield, but directly down Wilshire Blvd, meeting’s theme is a celebration of is a cluster of museums including the the 50th anniversary of the founding Peterson Automobile Museum, Arts Weapons of Mass In- of the Ethnomusicology Institute and and Crafts Museum, and the famed program at UCLA. While the primary Page Museum, home of the La Brea struction location of the meeting is the Wilshire Tar pits. -

Drummer, Give Me My Sound: Reflections on the Life and Legacy of Frisner Augustin1

Drummer, Give Me My Sound: Reflections on the Life and Legacy of Frisner Augustin1 by Lois WiLCken Ountògi, ba mwen son mwen e Sacred drummer, give me my sound, oh n , January 3 1981, I found myself Tanbouyè, ba mwen son mwen e Drummer, give me my sound, ah O waiting for my first lesson in Haitian Ountò, ba mwen son mwen Drum spirit, give me my sound drumming in a narrow hall outside a room Solèy leve2 The sun rises in a residential hotel on Broadway and West Photo 1: Frisner poses with his Madi Gra band, Port-au-Prince, circa middle to late 1960s. This is the first extant photo of Frisner Augustin, who plays the large drum in the center. Photo: Joujou Foto. Fall–Winter 2012, Volume 38:3–4 3 Haitian Vodou Haitian Vodou serves a pantheon of spirits as diverse as the African peoples who brought them to Haiti. The spirits (lwa) group into nations (nasyon), and the nations fall into one of two major branches, Rada and Petwo. Historically, Rada came from West Africa, particularly the region around the Guinea Gulf; Pet- wo came from the Congo region. Rada and Petwo differ markedly in tempera- ment and expressive style, and we see this in Vodou arts, ritual offerings, and the behaviors displayed in spirit possession. Vodouists may use the words Rada and Petwo to describe spirits, nations, rites, drums, and dances. The spirits of love and feminine power illustrate the Rada/Petwo dichotomy. Èzili Freda Dawomen, a Rada spirit traceable to West Africa, stands for ro- mantic love and luxury. -

Press Release

Press Release July 2010 Get Together for Haiti at Brooklyn Museum’s Target First Saturday on August 7 The Brooklyn Museum’s Target First Saturdays event attracts thousands of visitors to free programs of art and entertainment each month. The August 7 event focuses on Haiti and Brooklyn’s own Haitian community. Select programs are presented in collaboration with Haiti Cultural Exchange, a community- based nonprofit organization whose mission is to develop, present, and promote Haitian culture. Highlights of the evening include: 3–6 p.m. Dance Peniel Guerrier and Tamboula dance troupe, presented in conjunction with Haiti Cultural Exchange. 5–7 p.m. Music La Troupe Makandal uses Haitian drumming to represent Haiti’s history and culture. 5–10:30 p.m. Object of the Month Examine Lorraine O’Grady’s work Miscegenated Family Album, the Museum’s featured object for the month of August, with a Looking Closer guide. 6 p.m. Artist Talk Pierre Francillon responds to works in the exhibition Andy Warhol: The Last Decade. Presented in conjunction with Haiti Cultural Exchange. Free tickets available at the Visitor Center at 5 p.m. 6–7:30 p.m. Film Poto Mitan: Haitian Women, Pillars of the Global Economy (Renée Bergan and Mark Schuller, 2009, 50 min., NR). Documentary about the lives and struggles of Haitian women workers. Co-director Renée Bergan answers questions after the screening. Free tickets available at the Visitor Center at 5 p.m. 6:30–8:30 p.m. Hands-On Art Learn about the homemade instruments used by Haitian rara bands—including drums, horns, and shakers—and then make your own.