Triggering Terror: Illicit Gun Markets and Firearms Acquisition of Terrorist Networks in Europe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EU and Member States' Policies and Laws on Persons Suspected Of

DIRECTORATE GENERAL FOR INTERNAL POLICIES POLICY DEPARTMENT C: CITIZENS’ RIGHTS AND CONSTITUTIONAL AFFAIRS CIVIL LIBERTIES, JUSTICE AND HOME AFFAIRS EU and Member States’ policies and laws on persons suspected of terrorism- related crimes STUDY Abstract This study, commissioned by the European Parliament’s Policy Department for Citizens’ Rights and Constitutional Affairs at the request of the European Parliament Committee on Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs (LIBE Committee), presents an overview of the legal and policy framework in the EU and 10 select EU Member States on persons suspected of terrorism-related crimes. The study analyses how Member States define suspects of terrorism- related crimes, what measures are available to state authorities to prevent and investigate such crimes and how information on suspects of terrorism-related crimes is exchanged between Member States. The comparative analysis between the 10 Member States subject to this study, in combination with the examination of relevant EU policy and legislation, leads to the development of key conclusions and recommendations. PE 596.832 EN 1 ABOUT THE PUBLICATION This research paper was requested by the European Parliament's Committee on Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs and was commissioned, overseen and published by the Policy Department for Citizens’ Rights and Constitutional Affairs. Policy Departments provide independent expertise, both in-house and externally, to support European Parliament committees and other parliamentary bodies in shaping legislation -

Ecre Country Report 2005

European Council on Refugees and Exiles - Country Report 2005 ECRE COUNTRY REPORT 2005 This report is based on the country reports submitted by member agencies to the ECRE Secretariat between June and August 2005. The reports have been edited to facilitate comparisons between countries, but no substantial changes have been made to their content as reported by the agencies involved. The reports are preceded by a synthesis that is intended to provide a summary of the major points raised by the member agencies, and to indicate some of the common themes that emerge from them. It also includes statistical tables illustrating trends across Europe. ECRE would like to thank all the member agencies involved for their assistance in producing this report. The ECRE country report 2005 was compiled by Jess Bowring and edited by Carolyn Baker. 1 European Council on Refugees and Exiles - Country Report 2005 TABLE OF CONTENTS Austria..........................................................................................................................38 Belgium........................................................................................................................53 Bulgaria........................................................................................................................64 Czech Republic ............................................................................................................74 Denmark.......................................................................................................................84 -

THE CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC and Small Arms Survey by Eric G

SMALL ARMS: A REGIONAL TINDERBOX A REGIONAL ARMS: SMALL AND REPUBLIC AFRICAN THE CENTRAL Small Arms Survey By Eric G. Berman with Louisa N. Lombard Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies 47 Avenue Blanc, 1202 Geneva, Switzerland p +41 22 908 5777 f +41 22 732 2738 e [email protected] w www.smallarmssurvey.org THE CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC AND SMALL ARMS A REGIONAL TINDERBOX ‘ The Central African Republic and Small Arms is the most thorough and carefully researched G. Eric By Berman with Louisa N. Lombard report on the volume, origins, and distribution of small arms in any African state. But it goes beyond the focus on small arms. It also provides a much-needed backdrop to the complicated political convulsions that have transformed CAR into a regional tinderbox. There is no better source for anyone interested in putting the ongoing crisis in its proper context.’ —Dr René Lemarchand Emeritus Professor, University of Florida and author of The Dynamics of Violence in Central Africa ’The Central African Republic, surrounded by warring parties in Sudan, Chad, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, lies on the fault line between the international community’s commitment to disarmament and the tendency for African conflicts to draw in their neighbours. The Central African Republic and Small Arms unlocks the secrets of the breakdown of state capacity in a little-known but pivotal state in the heart of Africa. It also offers important new insight to options for policy-makers and concerned organizations to promote peace in complex situations.’ —Professor William Reno Associate Professor and Director of Graduate Studies, Department of Political Science, Northwestern University Photo: A mutineer during the military unrest of May 1996. -

Sovereign Sells US$1Bn Sukuk but Drops Conventional Tranches

MARCH 31 2018 ISSUE 2227 www.ifre.com Bargain basement Bahrain: sovereign sells US$1bn sukuk but drops conventional tranches Tesla stumbles as markets face reality: fatal crash and downgrade push bonds below 90 Deutsche Bank hangs Cryan out to dry: Achleitner sounds out replacement CEOs EQUITIES PEOPLE & MARKETS LOANS EMERGING MARKETS Jitters hurt Asia Successful Golden €7.3bn of debt to Mannai gets IPOs: listings Belt law suit fund leveraged Qatar Inc back from China and prompts broader buyout of Akzo in the US dollar India struggle disclaimers Nobel unit bond market 06 07 09 12 SAVE THE DATE: MAY 22 2018 GREEN FINANCING ROUNDTABLE TUESDAY MAY 22 2018 | THOMSON REUTERS BUILDING, CANARY WHARF, LONDON Sponsored by: Green bond issuance broke through the US$150bn mark in 2017, a 78% increase over the total recorded in 2016, and there are hopes that it will double again this year. But is it on track to reach the US$1trn mark targeted by Christina Figueres? This timely Roundtable will bring together a panel of senior market participants to assess the current state of the market, examine the challenges and opportunities and provide an outlook for the rest of the year and beyond. This free-to-attend event takes place in London on the morning of Tuesday May 22 2018. If you would like to be notified as soon as registration is live, please email [email protected]. Upfront OPINION INTERNATIONAL FINANCING REVIEW Dead man walking? Rocket man t was another terrible week for Deutsche Bank. But this ast November, an analyst at Germany’s Nord/LB said it Itime it wasn’t John Cryan’s fault. -

Differences in the South Dialects of Macedonian Language

DIFFERENCES IN THE SOUTH DIALECTS OF MACEDONIAN LANGUAGE Jadranka ANGELOVSKA University “Sf. Kiril and Metodius” Skopie, Macedonia Macedonian language is placed in the central part of the Balcanian Peninsula. It reaches the river Vardar and Struma and the south part of the river Mesta. From the west side the border is with R. Albania and goes to the south-west till the Lake Ohrid and Prespa. On the south side Macedonian language has border with the greek language, from the mountine Gramos till the river Mesta in Trakia. Macedonian language is spoken on the line Gramos-Ber-Solun (Thesaloniki). On the east side Macedonian language has border with Bulgarian language. On this part there is natural border, it’s the mountine Despat-Rila. On the nord side Macedonian language has border with Serbian language and the natural border is the mountine Koziak-Ruen-Skopska Crna Gora-Shar Planina-Korab. Nowdays, these are the borders of the Macedonian spoken territory. In the past, Macedonian Slavic population had reached spoken territory deeper in the west and south more than these borders which exist now. Lot of historical sources speak that the Slavic population was living in the South and Middle Albania, and on the South of Epir, Tesalia and the Nord Aegean Coust. Big part from the toponimes in these regions are Slavic. On the Macedonian-greek language region, actually in the Aegean part of Macedonia live mixed population – Macedonians and Greeks. We can hear Macedonian language spoken in the city Kostur, Lerin, Voden. In the registration of the population in the 1951 on this territory were living 250 000 Macedonians. -

Gun Law History in the United States and Second Amendment Rights

SPITZER_PROOF (DO NOT DELETE) 4/28/2017 12:07 PM GUN LAW HISTORY IN THE UNITED STATES AND SECOND AMENDMENT RIGHTS ROBERT J. SPITZER* I INTRODUCTION In its important and controversial 2008 decision on the meaning of the Second Amendment, District of Columbia v. Heller,1 the Supreme Court ruled that average citizens have a constitutional right to possess handguns for personal self- protection in the home.2 Yet in establishing this right, the Court also made clear that the right was by no means unlimited, and that it was subject to an array of legal restrictions, including: “prohibitions on the possession of firearms by felons and the mentally ill, or laws forbidding the carrying of firearms in sensitive places such as schools and government buildings, or laws imposing conditions and qualifications on the commercial sale of arms.”3 The Court also said that certain types of especially powerful weapons might be subject to regulation,4 along with allowing laws regarding the safe storage of firearms.5 Further, the Court referred repeatedly to gun laws that had existed earlier in American history as a justification for allowing similar contemporary laws,6 even though the court, by its own admission, did not undertake its own “exhaustive historical analysis” of past laws.7 In so ruling, the Court brought to the fore and attached legal import to the history of gun laws. This development, when added to the desire to know our own history better, underscores the value of the study of gun laws in America. In recent years, new and important research and writing has chipped away at old Copyright © 2017 by Robert J. -

A Question of Participation – Disengagement from The

Tina Wilchen Christensen A Question of Participation – Disengagement from the Extremist Right A case study from Sweden PhD dissertation The PhD program Social Psychology of Everyday Life Department of Psychology and Educational Studies Roskilde University October 2015 Tina Wilchen Christensen A Question of Participation – Disengagement from the Extremist Right. A case study from Sweden A publication in the series: PhD dissertations from the PhD program Social Psychology of Everyday Life, Roskilde University 1st Edition 2015 © The author, 2015 Cover: Vibeke Lihn Typeset: The author Print: Kopicentralen, Roskilde University, Denmark ISBN: 978-87-91387-88-3 Published by: The PhD program Social Psychology of Everyday Life Roskilde University Department of Psychology and Educational Studies Building 30C.2 P.O. Box 260 DK-4000 Roskilde Denmark Tlf: + 45 46 74 26 39 Email: [email protected] http://www.ruc.dk/en/research/phd-programme/doctoral-schools-and-phd- programmes-at-ru/doctoral-school-of-lifelong-learning-and-social-psychology-of- everyday-life/ All rights reserved. No parts of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. 2 Preface This dissertation has been developed in the PhD program “Social Psychology of Everyday Life”. As an original piece of work it is engaged in research prob- lems, interests and unique ways of developing knowledge and insight. It also contributes to the development of a new emerging field of psychological re- search: the social psychology of everyday life. -

Zoznam Zbraní, Ktoré Sa Môžu Zaradiť Do Kategórie B Podľa § 5 Ods. 1 Písm

Príloha č. 1 Zoznam zbraní, ktoré sa môžu zaradiť do kategórie B podľa § 5 ods. 1 písm. f) zákona č. 190/2003 Z.z. v znení neskorších predpisov Československo/ Česko : - samonabíjacia verzia Sa vz. 58, SA VZOR 58, ČZ 58, ČZ 58 COMPACT, SA VZ. 58 COMPACT, SA VZ. 58 SUBCOMPACT, SA VZOR 58 – SEMI, SAMOPAL VZOR 58, VZ. 58. I.P.S.C, IPSC GUĽOVNICA, CZ 858 TACTICAL, ARMS SPORTER, CZH 2003 S/K, FSN 01, FSN 01 LUX, FSN 01 URBAN - samonabíjacia verzia Sa vz. 23, 24, 25, 26, Sa vz. 61, - CZ 91S - samonabíjacia verzia guľometu vz. 26 - semiverzia CZ 805 Bren, CZ EVO Rusko a iné : - samonabíjacia verzia – PPŠ 41, PPS 43 - samonabíjacia verzia AK-47, AK 47 AKM, AK 74, AKS-74, AK – 101, 102, 103, 104, 105 , AK 107/108, AK-74, AKM, AKS - SAIGA Maďarsko: Verzie AKM, AMD, AK-63F 1 NDR Verzie AK47 Jugoslávia : Verzie M70AB1, M70AB2 Nemecko : Upravené do samonabíjacieho režimu streľby, resp. semi verzie - MP-18, MP-38, MP38/40, MP40, MP41, FG 42, MKb 42 (H), MKb 42(W), MP43, MP 44, HK G3, HK 33, HK 53, HK G36, HK SL8, HK 416, HK 417, semi HK MP5, GSG5, Nemecku vyrábaju nanovo samonabíjacie kópie vojnových samočinných zbrani pod novými názvami (prave pod nimi môzu byt dovezene) – pre ujasnenie vedľa v zátvorke uvádzame originálne zbrane, ktoré imitujú: BD 38 (MP 38) BD 3008 (MP 3008 – to je okopírovaný Sten) BD 42/I (FG 42/I) BD 42/II (FG 42/II) BD 42 (H) (MKB 42 H) BD 43/I (MP 43/I) BD 44 (MP 44) BD 1-5 (VG 1-5) Rakúsko : Samonabíjacia verzia Steyr AUG – 2, AK-INTERORDNANCE Belgicko : Samonabíjacia verzia FN FAL, FN CAL, FN FNC, FN F2000, FN SCAR SEMI AUTO Izrael : Úprava - Samonabíjacia verzia GALIL, GALIL ACE, GALIL ARM, GALIL SAR Úprava – UZI, Micro Uzi Španielsko : Samonabíjacie úpravy CETME verzie B,C,L Rumuni: Verzie AK-47 - AKM USA: Samonabíjacia verzia – Thompson 1928, Thompson M1A1 Samonabíjacia verzia – úprava/originál : - M-16, M-16A1, M-16A2, M-16A3, M-16A4, AR-10, AR-15, AR-18, M4, M4A1, Ruger Mini M14, Bushmaster M14, M16, M4, klony M16 a M4 – v USA je veľa firiem vyrábajúcich tieto klony (napr. -

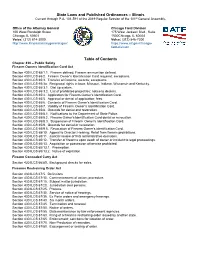

Illinois Current Through P.A

State Laws and Published Ordinances – Illinois Current through P.A. 101-591 of the 2019 Regular Session of the 101st General Assembly. Office of the Attorney General Chicago Field Division 100 West Randolph Street 175 West Jackson Blvd., Suite Chicago, IL 60601 1500Chicago, IL 60604 Voice: (312) 814-3000 Voice: (312) 846-7200 http://www.illinoisattorneygeneral.gov/ https://www.atf.gov/chicago- field-division Table of Contents Chapter 430 – Public Safety Firearm Owners Identification Card Act Section 430 ILCS 65/1.1. Firearm defined; Firearm ammunition defined. Section 430 ILCS 65/2. Firearm Owner's Identification Card required; exceptions. Section 430 ILCS 65/3. Transfer of firearms; records; exceptions. Section 430 ILCS 65/3a. Reciprocal rights in Iowa, Missouri, Indiana, Wisconsin and Kentucky. Section 430 ILCS 65/3.1. Dial up system. Section 430 ILCS 65/3.2. List of prohibited projectiles; notice to dealers. Section 430 ILCS 65/4. Application for Firearm Owner's Identification Card. Section 430 ILCS 65/5. Approval or denial of application; fees. Section 430 ILCS 65/6. Contents of Firearm Owner's Identification Card. Section 430 ILCS 65/7. Validity of Firearm Owner’s Identification Card. Section 430 ILCS 65/8. Grounds for denial and revocation. Section 430 ILCS 65/8.1. Notifications to the Department of State Police. Section 430 ILCS 65/8.2. Firearm Owner's Identification Card denial or revocation. Section 430 ILCS 65/8.3. Suspension of Firearm Owner's Identification Card. Section 430 ILCS 65/9. Grounds for denial or revocation. Section 430 ILCS 65/9.5. Revocation of Firearm Owner's Identification Card. -

Paraguay Country Report

SALW Guide Global distribution and visual identification Paraguay Country report https://salw-guide.bicc.de Weapons Distribution SALW Guide Weapons Distribution The following list shows the weapons which can be found in Paraguay and whether there is data on who holds these weapons: Beretta AR70/90 G IWI NEGEV G Browning M 2 G M79 G CZ Scorpion G Mauser K98 U FN FAL G MP UZI G FN High Power U SIG SG540 G HK G3 G Explanation of symbols Country of origin Licensed production Production without a licence G Government: Sources indicate that this type of weapon is held by Governmental agencies. N Non-Government: Sources indicate that this type of weapon is held by non-Governmental armed groups. U Unspecified: Sources indicate that this type of weapon is found in the country, but do not specify whether it is held by Governmental agencies or non-Governmental armed groups. It is entirely possible to have a combination of tags beside each country. For example, if country X is tagged with a G and a U, it means that at least one source of data identifies Governmental agencies as holders of weapon type Y, and at least one other source confirms the presence of the weapon in country X without specifying who holds it. Note: This application is a living, non-comprehensive database, relying to a great extent on active contributions (provision and/or validation of data and information) by either SALW experts from the military and international renowned think tanks or by national and regional focal points of small arms control entities. -

Proper Language, Proper Citizen: Standard Practice and Linguistic Identity in Primary Education

Proper Language, Proper Citizen: Standard Linguistic Practice and Identity in Macedonian Primary Education by Amanda Carroll Greber A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures University of Toronto © Copyright by Amanda Carroll Greber 2013 Abstract Proper Language, Proper Citizen: Standard Linguistic Practice and Identity in Macedonian Primary Education Doctor of Philosophy 2013 Amanda Carroll Greber Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures University of Toronto This dissertation analyzes how the concept of the ideal citizen is shaped linguistically and visually in Macedonian textbooks and how this concept changes over time and in concert with changes in society. It is focused particularly on the role of primary education in the transmission of language, identity, and culture as part of the nation-building process. It is concerned with how schools construct linguistic norms in association with the construction of citizenship. The linguistic practices represented in textbooks depict “good language” and thus index also “good citizen.” Textbooks function as part of the broader sets of resources and practices with which education sets out to make citizens and thus they have an important role in shaping young people’s knowledge and feelings about the nation and nation-state, as well as language ideologies and practices. By analyzing the “ideal” citizen represented in a textbook we can begin to discern the goals of the government and society. To this end, I conduct a diachronic analysis of the Macedonian language used in elementary readers at several points from 1945 to 2000 using a combination of qualitative and quantitative methods. -

The War and Fashion

F a s h i o n , S o c i e t y , a n d t h e First World War i ii Fashion, Society, and the First World War International Perspectives E d i t e d b y M a u d e B a s s - K r u e g e r , H a y l e y E d w a r d s - D u j a r d i n , a n d S o p h i e K u r k d j i a n iii BLOOMSBURY VISUAL ARTS Bloomsbury Publishing Plc 50 Bedford Square, London, WC1B 3DP, UK 1385 Broadway, New York, NY 10018, USA 29 Earlsfort Terrace, Dublin 2, Ireland BLOOMSBURY, BLOOMSBURY VISUAL ARTS and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published in Great Britain 2021 Selection, editorial matter, Introduction © Maude Bass-Krueger, Hayley Edwards-Dujardin, and Sophie Kurkdjian, 2021 Individual chapters © their Authors, 2021 Maude Bass-Krueger, Hayley Edwards-Dujardin, and Sophie Kurkdjian have asserted their right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identifi ed as Editors of this work. For legal purposes the Acknowledgments on p. xiii constitute an extension of this copyright page. Cover design by Adriana Brioso Cover image: Two women wearing a Poiret military coat, c.1915. Postcard from authors’ personal collection. This work is published subject to a Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial No Derivatives Licence. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher Bloomsbury Publishing Plc does not have any control over, or responsibility for, any third- party websites referred to or in this book.