Leveraging the Investment in Transit to Achieve Community & Economic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CODE of COLORADO REGULATIONS 8 CCR 1507-25 Division of State Patrol

DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC SAFETY Division of State Patrol RULES AND REGULATIONS CONCERNING THE PERMITTING, ROUTING & TRANSPORTATION OF HAZARDOUS AND NUCLEAR MATERIALS AND THE INTRASTATE TRANSPORTATION OF AGRICULTURAL PRODUCTS IN THE STATE OF COLORADO 8 CCR 1507-25 [Editor’s Notes follow the text of the rules at the end of this CCR Document.] _________________________________________________________________________ AUTHORITY The Chief of the Colorado State Patrol (CSP) is authorized by §42-20-108 (1) and (2) and §§42-20-403, 504, and 508, CRS, to promulgate rules and regulations for the permitting, routing and safe transportation of hazardous and nuclear materials by motor vehicle within the state of Colorado, both in interstate and intrastate transportation. Pursuant to §42-20-108.5, CRS, the Chief of the CSP is authorized to adopt rules and regulations which exempt agricultural products from the hazardous materials rules. APPLICABILITY These rules and regulations shall apply to all persons who transport, ship or cause to be transported or shipped, a hazardous material by motor vehicle over the public roads of this state. COMPLIANCE WITH 8 CCR 1507-1 All commercial vehicles that transport hazardous and/or nuclear materials shall comply with the rules and regulations found at 8 CCR 1507-1, Concerning the Minimum Standards for the Operation of Commercial Vehicles. GENERAL DEFINITIONS Unless otherwise specified, definitions of general applicability throughout these rules are: Enforcement Official: As identified within §42-20-103 (2), CRS, the definition of enforcement official is limited to a peace officer who is an officer of the CSP as described in §§16-2.5-101 and 114, CRS; a certified peace officer who is a certified Port of Entry (POE) officer as described in §§16-2.5-101 and 115, CRS; a peace officer who is an investigating official of the Public Utilities Commission (PUC) transportation section as described in §§16-2.5-101 and 143, CRS; or any peace officer as described in §16-2.5-101, CRS. -

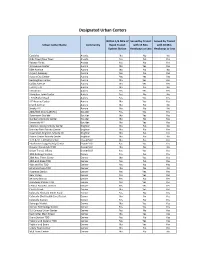

Designated Urban Centers

Designated Urban Centers Within 1/4 Mile of Served by Transit Served by Transit Urban Center Name Community Rapid Transit with 15 Min. with 30 Min. System Station Headways or Less Headways or Less Candelas ArvadaNoNoNo Olde Town/New Town Arvada Yes No Yes Ralston Fields Arvada Yes No Yes 1st Avenue Center Aurora No Yes Yes 56th Avenue Aurora No No No Airport Gateway Aurora Yes No Yes Aurora City Center Aurora Yes Yes Yes Buckingham Center Aurora No Yes Yes Colfax Avenue Aurora No Yes Yes E‐470 / I‐70 Aurora No No No Fitzsimons Aurora Yes Yes Yes Hampden Town Center Aurora Yes No No I‐225/Parker Road Aurora Yes Yes Yes Iliff Avenue Center Aurora No Yes Yes Jewell Avenue Aurora No No No Smoky Hill Aurora No No No 28th/30th Streets (BVRC) Boulder Yes Yes Yes Downtown Boulder Boulder No Yes Yes Gunbarrel Activity Center Boulder No No Yes University Hill Boulder No Yes Yes Adams Crossing Activity Center Brighton No No No Bromley Park Activity Center Brighton No No Yes Downtown Brighton Activity Ctr Brighton No No Yes Prairie Center Activity Center Brighton No No No 1‐25 & SH 7 Activity Center Broomfield No No Yes Interlocken Loopp Activityy Center Broomfield Yes Yes Yes Original Broomfield TODBroomfieldNoNoNo Urban Transit Village Broomfield Yes Yes Yes 10th & Osage Station Denver Yes No Yes 29th Ave. Town Center Denver No Yes Yes 38th and Blake TOD Denver Yes No Yes 41st and Fox TOD Denver Yes No Yes 62nd and Pena TODDenverNoNoNo Alameda Station Denver Yes Yes Yes Bear Valley Denver No Yes Yes Bellview Station Denver Yes No Yes Broadway Station -

Next Steps Study

Prepared for: City of Englewood 1000 Englewood Parkway Englewood, CO 80110-2373 City of Sheridan 4101 S. Federal Boulevard Sheridan, CO 80110-5399 Prepared by: Felsburg Holt & Ullevig 6300 S. Syracuse Way, Suite 600 Centennial, CO 80111 In Association With: ArLand LLC Bachman PR Design Workshop Toole Design Group Table of Contents Page Executive Summary -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ES-1 Acknowledgements ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ ES-18 1.0 Introduction -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 1 1.1 Study Location and Description -------------------------------------------------2 1.2 Vision ---------------------------------------------------------------------------- 5 1.3 Objectives ----------------------------------------------------------------------- 5 1.4 Planning Context ---------------------------------------------------------------- 5 1.4.1 South Santa Fe Drive Corridor Improvements Study ------------------- 6 1.4.2 North Englewood Small Area Plan -------------------------------------- 6 1.4.3 CityCenter Englewood: Redevelopment of the Cinderella City Mall -- 6 1.4.4 Englewood Industrial Urban Renewal Plan and the General Ironworks Development Plan ------------------------------------------- 7 1.4.5 Southwest Light Rail Transit Line Major Investment Study ------------- 7 1.4.6 Englewood Civic Center Pedestrian Underpass Feasibility Study ----- 7 -

Residence Inn Hotel Aurora, CO Traffic Impact Study

Residence Inn Hotel Aurora, CO Traffic Impact Study Prepared For: Shiva Investments LLC 800 S. Abilene Street Aurora, CO 80012 City of Aurora Public Works Department 15151 E. Alameda Parkway, Suite 3200 Aurora, CO 80012 Prepared By: JR Engineering, LLC 7200 S. Alton Way, C400 Centennial, CO 80112 Contact: Eli Farney, PE, PTOE August 24, 2018 Residence Inn Hotel Aurora, CO Table of Contents Section 1: Introduction ........................................................................................................ 1 Section 2: Existing Conditions............................................................................................ 1 Proposed Zoning ............................................................................................................. 2 Study Area Boundaries ................................................................................................... 4 Existing Roadway and Transportation Network Description ......................................... 4 Data Collection ............................................................................................................... 5 Section 3: Proposed Conditions .......................................................................................... 7 Trip Generation ............................................................................................................... 7 Project Trip Distribution ................................................................................................. 7 Project Trip Assignment ................................................................................................ -

Concept of Operations Draft V04: 9/2015 I-70 East Tolled Express Lanes

Concept of Operations Draft V04: 9/2015 I-70 East Tolled Express Lanes VERSION CONTROL DATE VERSION AUTHOR COMMENTS (INCLUDING REVIEW HISTORY) M. Moradi, A. Skinner, K. DePinto, D. Sprague, D. June 2015 Draft V0.1 R. Harb Liddle August 2015 Draft V0.3 M. Moradi Comments September Draft V0.4 R. Harb Comments reviews 2015 Concept of Operations i Draft V0.4 ACRONYMS ACRONYM DESCRIPTION AASHTO American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials AET All Electronic Tolling ALPR Automatic License Plate Recognition ATM Active Traffic Management ATMS Advanced Traffic Management System ATR Automatic Traffic Recorder AVI Automatic Vehicle Identification AVC Automatic Vehicle Classification BOS Back Office System CCTV Closed-Circuit Television CDOT Colorado Department of Transportation CSC Customer Service Center CSP Colorado State Patrol CTMC Colorado Transportation Management Center CTMS Colorado Transportation Management System DMV Department of Motor Vehicles DRCOG Denver Regional Council of Governments DWL Double White Line Crossing E-470 E-470 Public Highway Authority ELOM Express Lanes Operations Manager ETC Electronic Toll Collection ETTM Electronic Tolling and Traffic Management FHWA Federal Highway Administration Free Flow Traffic moving freely without significant oscillation in average speed GP lanes General-Purpose Lanes HOT High Occupancy Toll HOV High Occupancy Vehicle HOV 2+ Two-or-more Person Carpool HOV 3+ Three-or-more Person Carpool HPTE High Performance Transportation Enterprise ICD Interface Control Document ILEV -

City of Littleton 2255 West Berry Avenue Littleton, CO 80120 Meeting Agenda

Littleton Center City of Littleton 2255 West Berry Avenue Littleton, CO 80120 Meeting Agenda Planning Commission Monday, January 9, 2017 6:30 PM Community Room Study Session 1. RTD and Southwest Rail Extension Updates a. ID# 17-10 Kent Bagley, Regional Transportation District, Board of Directors, District H Attachments: RTD Directors Map - District H 2. Board and Staff Updates The public is invited to attend all regular meetings or study sessions of the City Council or any City Board or Commission. Please call 303-795-3780 at least forty-eight (48) hours prior to the meeting if you believe you will need special assistance or any reasonable accommodation in order to be in attendance at or participate in any such meeting. For any additional information concerning City meetings, please call the above referenced number. City of Littleton Page 1 Printed on 1/5/2017 Littleton Center City of Littleton 2255 West Berry Avenue Littleton, CO 80120 Staff Communication File #: ID# 17-10, Version: 1 City of Littleton Page 1 of 1 Printed on 1/5/2017 powered by Legistar™ College View / South Platte Englewood Station Nine Mile Station 95 391 UV Harvey Park South FLOYD AV Wellshire 2 University Hills Hampden UV LAKEWOOD Bear Valley UV88 UV Nine Mile Station ZUNI ST HAMPDEN AV 285 30 Kennedy AURORA UV391 9E Wadsworth / Hampden UV95 Englewood Station ¤£285 ¤£285 E HAPPY CANYON RD¤£ UV I Southmoor Station S LOWELLS BLVD 225 0 0.5 1 KENYON AV AURORA ¨¦§ 83 ELATI ST ELATI UV Southmoor Station YOSEMITES ST Miles CLARKSONST Southmoor Park SHERIDAN DENVER Dayton -

2035 Metro Vision Regional Transportation Plan

Denver Regional Council of Governments 2035 Metro Vision Regional Transportation Plan Appendix 1 Denver Region Multimodal Corridor Visions Adopted December 19, 2007 Preparation of this report has been financed in part through grants from the U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Transit Administration, and Federal Highway Administration. Disclaimer: The data in this report are compiled from multiple sources and are intended for informational purposes only. DRCOG assumes no responsibility or legal liability for the accuracy, completeness or usefulness of any information in this report. ii Table of Contents 1. INTRODUCTION............................................................................................................................... 1 A. Overview of Appendix.................................................................................................................................. 1 B. Implementation Priorities.............................................................................................................................. 1 2. COMMON STRATEGIES FOR ALL CORRIDOR VISIONS IN DRCOG REGION ............................. 5 A. Overall .......................................................................................................................................................... 5 B. Transit Facilities and Services ...................................................................................................................... 5 C. Travel Demand Management....................................................................................................................... -

AGENCY PROFILE and FACTS RTD Services at a Glance

AGENCY PROFILE AND FACTS RTD Services at a Glance Buses & Rail SeniorRide SportsRides Buses and trains connect SeniorRide buses provide Take RTD to a local the metro area and offer an essential service to our sporting event, Eldora an easy RTDway to Denver services senior citizen at community. a glanceMountain Resort, or the International Airport. BolderBoulder. Buses and trains connect and the metro trainsarea and offer an easy way to Denver International Airport. Access-a-Ride Free MallRide Access-a-RideAccess-a-Ride helps meet the Freetravel MallRideneeds of passengers buses with disabilities.Park-n-Rides Access-a-RideFlexRide helps connect the entire length Make connections with meet theFlexRide travel needsbuses travel of within selectof downtown’s RTD service areas.16th Catch FlexRideour to connect buses toand other trains RTD at bus or passengerstrain with servies disabilities. or get direct accessStreet to shopping Mall. malls, schools, and more.89 Park-n-Rides. SeniorRide SeniorRide buses serve our senior community. Free MallRide FlexRideFree MallRide buses stop everyFree block onMetroRide downtown’s 16th Street Mall.Bike-n-Ride FlexRideFree buses MetroRide travel within Free MetroRide buses Bring your bike with you select RTDFree service MetroRide areas. buses offer convenientoffer convenient connections rush-hour for downtown commuterson the bus along and 18th train. and 19th Connectstreets. to other RTD connections for downtown SportsRides buses or trains or get direct commuters along 18th and Take RTD to a local sporting event, Eldora Mountain Resort, or the BolderBoulder. access toPark-n-Rides shopping malls, 19th streets. schools, Makeand more.connections with our buses and trains at more than 89 Park-n-Rides. -

I-25 Central Planning and Environmental Linkages (PEL) Study

Existing Conditions Assessment I-25 Central Planning and Environmental Linkages (PEL) Study 2829 W. Howard Pl. Denver, CO 80204 [email protected] i25centralpel.codot.us This page intentionally left blank. Existing Conditions Assessment Contents Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 1 Study Location and Description ........................................................................................................ 1 Public and Stakeholder Engagement ............................................................................................... 3 Feedback Received To-Date ...................................................................................................... 5 Transportation Planning Context ....................................................................................................... 7 The History of I-25 Central ............................................................................................................... 7 Existing Land Use Context ............................................................................................................... 7 Section 1: 20th Street to Colfax Avenue ..................................................................................... 8 Section 2: Colfax Avenue to US 6/6th Avenue ............................................................................ 8 Section 3: US 6/6th Avenue to Santa Fe Drive/US 85 ............................................................. -

January 2014 Service Changes

BOARD OF DIRECTORS REPORT To: Phillip A. Washington, General Manager Date: October 10, 2013 From: Bruce Abel, Assistant General Manager GM Date: October 8, 2013 Board Meeting Date: October 15, 2013 Subject: January 2014 Service Changes RECOMMENDED ACTION It is recommended by the Operations/Customer Services Committee that the Board of Directors approve the January 2014 Service Change package as revised and summarized in Attachment A resulting in an annualized cost increase of approximately $635,500 and, further, to authorize the General Manager or his designee to execute contract amendments as necessary for private operators whose service is impacted by these changes. DISCUSSION To meet the diverse travel needs of the citizens of the District and maintain a high-performance, sustainable transit system, RTD has developed a networked family of services for which the different classes of service have different expectations of performance. We will continue adjusting services in response to changes in ridership and operational performance of the transit system as a whole while also continuing to review the impacts of the implementation of the West Corridor Light Rail Service and the associated bus service changes. Routine service changes not associated with or included in the West Corridor Service Plan are necessary to maintain system on-time performance and provide the appropriate level of service according to customer demand while we will also need to monitor customer response to the implementation of West Corridor bus and rail service and -

Rails to Real Estate Development Patterns Along

Rails to Real Estate Development Patterns along Three New Transit Lines March 2011 About This Study Rails to Real Estate was prepared by the Center for Transit-Oriented Development (CTOD). The CTOD is the only national nonprofit effort dedicated to providing best practices, research and tools to support market- based development in pedestrian-friendly communities near public transportation. We are a partnership of two national nonprofit organizations – Reconnecting America and the Center for Neighborhood Technology – and a research and consulting firm, Strategic Economics. Together, we work at the intersection of transportation planning, regional planning, climate change and sustainability, affordability, economic development, real estate and investment. Our goal is to help create neighborhoods where young and old, rich and poor, can live comfortably and prosper, with affordable and healthy lifestyle choices and ample and easy access to opportunity for all. Report Authors This report was prepared by Nadine Fogarty and Mason Austin, staff of Strategic Economics and CTOD. Additional support and assistance was provided by Eli Popuch, Dena Belzer, Jeff Wood, Abigail Thorne-Lyman, Allison Nemirow and Melissa Higbee. Acknowledgements The Center for Transit-Oriented Development would like to thank the Federal Transit Administration. The authors are also grateful to several persons who assisted with data collection and participated in interviews, including: Bill Sirois, Denver Regional Transit District; Catherine Cox-Blair, Reconnecting America; Caryn Wenzara, City of Denver; Frank Cannon, Continuum Partners, LLC; Gideon Berger, Urban Land Institute/Rose Center; Karen Good, City of Denver; Kent Main, City of Charlotte; Loretta Daniel, City of Aurora; Mark Fabel, McGough; Mark Garner, City of Minneapolis; Michael Lander, Lander Group; Norm Bjornnes, Oaks Properties LLC; Paul Mogush, City of Minneapolis; Peter Q. -

Broncosride Pickup Schedule for December 22, 2019

BroncosRide and Light Rail Service page 1 of 2 BroncosRide Schedule for: Sunday, December 22, 2019 Route: Park-n-Ride / Stop / Station Times are approximate Post game bus location** BR26: Dry Creek & University 11:35 AM 11:40 AM 11:45 AM every 5-10 minutes until 12:55 PM Row 22 Arapahoe High School BR24: Alameda Havana 12:25 PM 12:40 PM 12:55 PM Row 21 BR10: Boulder High School 11:35 AM 11:55 AM 12:15 PM Row15-16 Arapahoe & 17th BR32: El Rancho 12:00 PM 12:15 PM 12:35 PM Row 4 BR32: Evergreen 11:45 AM 12:00 PM 12:20 PM Row 4 BR38: Federal Shuttle: Lincoln HS (Hazel Ct & Iliff) and bus stops on Federal Blvd 11:35 AM 11:40 AM 11:45 AM every 5 - 10 minutes until 1:50 PM Row 28 between Evans and 8th Ave BR20: Longmont Park-n-Ride 11:30 AM 11:35 AM 11:45 AM 11:50 AM 12:00 PM 12:10 PM 12:20 PM 12:30 PM Rows 17-18 815 South Main Street BR44: Nine Mile (Ga te F) 11:35 AM 11:40 AM 11:45 AM every 5-10 minutes until 1:00 PM Rows 23-24 BR8: Olde Town Arvada Discontinued Discontinued: Ride G-Line to DUS and Transfer to C, E or W-Lines to Broncos Stadium BR48: Parker 11:35 AM 11:45 AM 11:50 AM 12:00 PM 12:15 PM 12:30 PM Row 19 BR48: Pinery 11:35 AM 11:40 AM 11:50 AM 12:05 PM 12:20 PM Row 19 BR56: South High School 11:40 AM 11:50 AM 12:00 PM 12:10 PM 12:20 PM 12:35 PM 12:50 PM Row 26 Louisiana & Gilpin BR4: Thornton (Gate C) 11:40 AM 11:45 AM 11:45 AM every 5-10 minutes until 1:35 PM Rows 9-12 BR10: US 36 & Broomfield Station (Gate 11:35 AM 11:45 AM 11:55 AM 12:05 PM 12:15 PM 12:25 PM 12:45 PM Rows 15-16 K) BR10: US 36 & McCaslin Stn (Gate A) 11:45