Authorship and Individualism in American Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Maryland Historical Magazine, 1941, Volume 36, Issue No. 1

ma SC 5Z2I~]~J41 MARYLAND HISTORICAL MAGAZINE PUBLISHED UNDER THE AUTHORITY OF THE MARYLAND HISTORICAL SOCIETY VOLUME XXXVI BALTIMORE 1941 CONTENTS OF VOLUME XXXVI PAGE THE SUSQUEHANNOCK FORT ON PISCATAWAY CREEK. By Alice L. L. Ferguson, 1 ELIZA GODBFROY: DESTINY'S FOOTBALL. By William D. Hoyt, Jr., ... 10 BLUE AND GRAY: I. A BALTIMORE VOLUNTEER OF 1864. By William H. fames, 22 II. THE CONFEDERATE RAID ON CUMBERLAND, 1865. By Basil William Spalding, 33 THE " NARRATIVE " OF COLONEL JAMES RIGBIE. By Henry Chandlee Vorman, . 39 A WEDDING OF 1841, 50 THE LIFE OF RICHARD MALCOLM JOHNSTON IN MARYLAND, 1867-1898. By Prawds Taylor Long, concluded, 54 LETTERS OF CHARLES CARROLL, BARRISTER, continued, 70, 336 BOOK REVIEWS, 74, 223, 345, 440 NOTES AND QUERIES, 88, 231, 354, 451 PROCEEDINGS OF THE SOCIETY, 90, 237, 455 LIST OF MEMBERS, 101 THE REVOLUTIONARY IMPULSE IN MARYLAND. By Charles A. Barker, . 125 WILLIAM GODDARD'S VICTORY FOR THE FREEDOM OF THE PRESS. By W. Bird Terwilliger, 139 CONTROL OF THE BALTIMORE PRESS DURING THE CIVIL WAR. By Sidney T. Matthews, 150 SHIP-BUILDING ON THE CHESAPEAKE: RECOLLECTIONS OF ROBERT DAWSON LAMBDIN, 171 READING INTERESTS OF THE PROFESSIONAL CLASSES IN COLONIAL MARYLAND, 1700-1776. By Joseph Towne Wheeler, 184, 281 THE HAYNIE LETTERS 202 BALTIMORE COUNTY LAND RECORDS OF 1687. By Louis Dow Scisco, . 215 A LETTER FROM THE SPRINGS, 220 POLITICS IN MARYLAND DURING THE CIVIL WAR. By Charles Branch Clark, . 239 THE ORIGIN OF THE RING TOURNAMENT IN THE UNITED STATES. By G. Harrison Orians, 263 RECOLLECTIONS OF BROOKLANDWOOD TOURNAMENTS. By D. Sterett Gittings, 278 THE WARDEN PAPERS. -

THE Chap-Book SEMI-MONTHLY

DELOS AVERY 425 SURF ST. CHICAGO iiiii'iCJS HSSTQR5CAL SUkVcV THE Chap- Book A MISCELLANY of Curious and Interesting Songs, Ballads, Tales, Histories, &c. ; adorned with a variety of pictures and very delightful to read ; newly composed by MANY CELEBRATED WRITERS; To which are annexM a LARGE COLLECTION of Notices of BOOKS. VOLUME L From May i^ib to November 1st A.D. MDCCCXC IV CHICAGO Printed for Stone &' Kimball o^ the Caxton Building where Shopkeepers^ Hawkersy and others are supplied DELOS AVERY 42S SURF ST. CHICAGO CKAB 1 INDEX TO VOLUME I POETRY ALDRICH, THOMAS BAILEY page ORIGINALITY 247 PESSIMISTIC POETS I03 BROWN, ALICE TRILBY 91 CARMAN, BLISS NANCIBEL 103 THE PRAYER IN THE ROSE GARDEN 34 CRAM, RALPH ADAMS THE RIDE OF THE CLANS I39 GOETZ, P. B. QUATRAINS 344 HALL, GERTRUDE MOONLIGHT, TRANSLATED FROM PAUL VERLAINE 7 VERSES 184 HENDERSON, W. J. ASPIRATION 335 HOVEY, RICHARD HUNTING SONG 253 THE SHADOWS KIMBALL, HANNAH PARKER PURITY 223 MOODY, WILLIAM VAUGHN A BALLADE OF DEATH-BEDS 5I MORRIS, HARRISON S. PARABLE 166 00 MOULTON, LOUISE CHANDLER page IN HELEN'S LOOK I96 WHO KNOWS? 27 MUNN, GEORGE FREDERICK THE ENCHANTED CITY 1 27 PARKER, GILBERT THERE IS AN ORCHARD 331 PEABODY, JOSEPHINE PRESTON THE WOMAN OF THREE SORROWS I34 ROBERTS, CHARLES G. D. THE UNSLEEPING 3 SCOLLARD, CLINTON THE WALK 183 SHARP, WILLIAM TO EDMUND CLARENCE STEDMAN 212 TAYLOR, J. RUSSELL THE NIGHT RAIN I27 VERLAINE, PAUL EPIGRAMMES 211 MOONLIGHT, TRANSLATED BY GERTRUDE HALL 7I YELLOW BOOK-MAKER, THE 4I PROSE ANNOUNCEMENTS I9, 43, 73, 96, I18, I47, I75, 204, 242, 266, 357 B. -

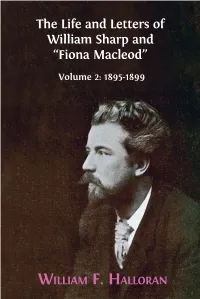

Fiona Macleod”

The Life and Letters of William Sharp and “Fiona Macleod” Volume 2: 1895-1899 W The Life and Letters of ILLIAM WILLIAM F. HALLORAN William Sharp and What an achievement! It is a major work. The lett ers taken together with the excellent H F. introductory secti ons - so balanced and judicious and informati ve - what emerges is an amazing picture of William Sharp the man and the writer which explores just how “Fiona Macleod” fascinati ng a fi gure he is. Clearly a major reassessment is due and this book could make it ALLORAN happen. Volume 2: 1895-1899 —Andrew Hook, Emeritus Bradley Professor of English and American Literature, Glasgow University William Sharp (1855-1905) conducted one of the most audacious literary decep� ons of his or any � me. Sharp was a Sco� sh poet, novelist, biographer and editor who in 1893 began The Life and Letters of William Sharp to write cri� cally and commercially successful books under the name Fiona Macleod. This was far more than just a pseudonym: he corresponded as Macleod, enlis� ng his sister to provide the handwri� ng and address, and for more than a decade “Fiona Macleod” duped not only the general public but such literary luminaries as William Butler Yeats and, in America, E. C. Stedman. and “Fiona Macleod” Sharp wrote “I feel another self within me now more than ever; it is as if I were possessed by a spirit who must speak out”. This three-volume collec� on brings together Sharp’s own correspondence – a fascina� ng trove in its own right, by a Victorian man of le� ers who was on in� mate terms with writers including Dante Gabriel Rosse� , Walter Pater, and George Meredith – and the Fiona Macleod le� ers, which bring to life Sharp’s intriguing “second self”. -

American Book-Plates, a Guide to Their Study with Examples;

BOOK PLATE G i ? Y A 5 A-HZl BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME PROM THE SAGE ENDOWMENT "FUND THE GIFT OF Weuru m* Sage 1891 /un^x umtim 1969 MB MAR 2 6 79 Q^tJL Cornell University Library Z994.A5 A42 American book-plates, a guide to their s 3 1924 029 546 540 olin Cornell University Library The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924029546540 AMERICAN BOOK-PLATES (EX-LIBRIS) j&m. American Book-Plates A Guide to their Study with Examples By Charles Dexter Allen Member Ex-Libris Society London • Member Grolier Club New York Member Connecticut Historical Society Hartford With a Bibliography by Eben Newell Hewins Member Ex-Libris Society Illustrated with many reproductions of rare and interesting book-plates and in the finer editions with many prints from the original coppers both old and recent * ^XSU-- 1 New York • Macmillan and Co. • London Mdcccxciv All rights reserved : A-77<*0T Copyright, 1894, By MACMILLAN AND CO. NotfoootJ JSrniB — Berwick Smith. J. S. Cushing & Co. & Boston, Mass., U.S.A. PREFACE. a ^ew ears Book-plate i, ^ litera- II , i|i|lW|lfl|||| Y ture w*^ ^ ave a ace n tne iiSill illllll P^ ' mWnmi i&lfflBH catalogues of the Libraries, as it now has in those of the dealers in books. The works of the Hon. J. Leicester Warren (Lord de Tabley), Mr. Egerton Castle, and Mr. W. J. Hardy on the English plates, Mr. -

Comic Actors and Comic Acting on the 19Th Century American Stage

"Those That Play Your Clowns:" Comic Actors and Comic Acting on the 19th Century American Stage Barnard Hewitt (Barnard Hewitt's Fellows Address was delivered at the ATA Convention in Chicago, August 16, 1977.) It seems to me that critics and historians of theatre have neglected comedians and the acting of comedy, and I ask myself why should this be so? Nearly everyone enjoys the acting of comedy. As the box office has regularly demonstrated, more people enjoy comedy than enjoy serious drama. I suspect that comedy and comedians are neglected because critics and scholars feel, no doubt unconsciously that because they arouse laughter rather than pity and fear, they don't deserve serious study. Whatever the reason for this neglect, it seems to me unjust. In choosing the subject for this paper, I thought I might do something to redress that injustice. I hoped to identify early styles of comic acting on our stage, discover their origins in England, note mutations caused by their new environment, and take note of their evolution into new styles. I don't need to tell you how difficult it is to reconstruct with confidence the acting style of any period before acting was recorded on film. One must depend on what can be learned about representative individuals: about the individual's background, early training and experience, principal roles, what he said about acting and about his roles, pictures of him in character, and reports by his contemporaries - critics and ordinary theatregoers - of what he did and how he spoke. First-hand descriptions of an actor's performance in one or more roles are far and away the most enlightening evidence, but nothing approaching Charles Clarke's detailed description of Edwin Booth's Hamlet is available for an American comic actor.1 Comedians have written little about their art.2 What evidence I found is scattered and ambiguous when it is not contradictory. -

Lauren Ford Collection -- the Little Book About God

Helen & Marc Younger Pg 25 [email protected] LAUREN FORD COLLECTION -- THE LITTLE BOOK ABOUT GOD. NY: Doubleday Doran 1934 (1934). 113. FORD,LAUREN. COLLECTION. We are pleased to be able to offer 8vo, full red leather binding with gilt decorations (by the French Binders), this interesting collection of Lauren Ford material including special copies of Fine. Stated 1st edition. THIS IS ONE OF ONLY TWO COPIES SPECIALLY books, original art and more. Lauren Ford (1891-1973) was not only an award BOUND BY THE PUBLISHER WITH AN EXQUISITE ORIGINAL SIGNED winning illustrator of children’s books but she wrote them as well. According WATERCOLOR BY FORD BOUND IN. Laid in is a letter from the original owner to her mother, she began to draw at the age of only four and eventually (who was Ford’s editor at Doubleday) discussing the production process and studied with F.V. du Mond and George Bridgman. She began professionally the difficulty and expense of printing in 7 colors. She notes: “ The text was by illustrating her mother’s books and dust wrappers (her mother was noted scrawled in ink by Lauren...Marguerite hand-lettered the whole thing for me as children’s author Julia Ellsworth Ford). She first collaborated with her mother a work of love because she had always admired Lauren’s paintings and wanted to on Imagina which was illustrated by Arthur Rackham. In 1923 she illustrated help me to make this little book a possibility.” With hand-lettered text, this entirely on her own, her mother’s book Pan and Santa Claus. -

The Digital Mapping of Literary Edinburgh James Loxley, Beatrice

‘Multiplicity Embarrasses the Eye’: the Digital Mapping of Literary Edinburgh James Loxley, Beatrice Alex, Miranda Anderson, Uta Hinrichs, Claire Grover, David Harris-Birtill, Tara Thomson, Aaron Quigley, and Jon Oberlander (Universities of Edinburgh and St Andrews) Literature, Geocriticism, and Digital Opportunities There has long been a deep intertwining of the concepts, experiences and memories of space and place and the practice of literature. But while it might be possible to conduct a spatially- aware critical analysis of any text, not all texts manifest such self-conscious spatial awareness. Literary history, nevertheless, is rich with genres and modes that do, from classical pastoral and renaissance estate verse to metadrama, utopian writing and concrete poetry. Any critic seeking to give an analytical account of such writing will find it hard to overlook its immersive engagement with space and spatiality. And literary criticism has also enriched its vocabulary with concepts drawn from a range of modern and contemporary theoretical sources. Mikhail Bakhtin’s notion of the chronotope, he suggested, named ‘a formally constitutive category of literature’, marking an irreducible spatiality (intertwined, for Bakhtin, with temporality) which was yet manifest only in particular, historically and generically specific, configurations.1 Michel de Certeau developed a very different approach, distinguishing space from place in a distinctive fashion that has had a significant influence on literary critics.2 Yu Fu Tuan’s own conceptualisation of this distinction has also had a literary critical resonance.3 Henri Lefebvre’s account of the ‘production of space’, with its conceptual triad of ‘spatial practice’, ‘representation of space’ and ‘representational space’, has also exerted its pull.4 Recently, however, literary critical interest in spatiality has reached a new intensity. -

Curriculum Vitae D. GRAHAM BURNETT EDUCATION HONORS and AWARDS RESEARCH FELLOWSHIPS

Curriculum Vitae D. GRAHAM BURNETT Professor, Princeton University HISTORY DEPARTMENT AND PHONE : 609.258.7309 PROGRAM IN HISTORY OF SCIENCE FAX : 609.258.5326 129 DICKINSON HALL DBURNETT@ PRINCETON. EDU PRINCETON, NJ 08544- 1017 205 DICKINSON EDUCATION Cambridge University, Trinity College, 1993-1997 (Director: James A. Secord) Ph.D., History and Philosophy of Science, requirements fulfilled 1997 (degree awarded 2001) Dissertation: “El Dorado on Paper: Traverse Surveys and the Geographical Construction of British Guiana, 1803-1844” M.Phil., History and Philosophy of Science, 1994 Thesis: “Science and Colonial Exploration: Interior Expeditions and the Amerindians of British Guiana, 1820-1845” Princeton University, 1989-1993 A.B., Summa cum Laude, History (Program in History of Science), 1993 Class rank: GPA second overall in class of 1993 (see “Salutatorian,” below) Thesis: “Mechanical Lens Making in the Seventeenth Century: Philosophers, Artisans, and Machines” HONORS AND AWARDS New York City Book Award, New York Society Library, 2008 Hermalyn Prize in Urban History, Bronx Historical Society, 2008 Christian Gauss Fund University Preceptorship, Princeton University, 2004-2007 Nebenzahl Prize in the History of Cartography, Newberry Library, Chicago, 1999 Senior Rouse Ball Studentship, Trinity College, Cambridge, full-year research prize, 1997 Marshall Scholar, 1993-1995 Richard Casement Internship, The Economist, London, international competition, 1994 Moses Taylor Pyne Prize, highest undergraduate award at Princeton University, 1993 Salutatorian, -

Angels Who Stepped Outside Their Houses: “American True Womanhood” and Nineteenth-Century (Trans)Nationalisms

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations Dissertations and Theses March 2020 ANGELS WHO STEPPED OUTSIDE THEIR HOUSES: “AMERICAN TRUE WOMANHOOD” AND NINETEENTH-CENTURY (TRANS)NATIONALISMS Gayathri M. Hewagama University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2 Part of the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Hewagama, Gayathri M., "ANGELS WHO STEPPED OUTSIDE THEIR HOUSES: “AMERICAN TRUE WOMANHOOD” AND NINETEENTH-CENTURY (TRANS)NATIONALISMS" (2020). Doctoral Dissertations. 1830. https://doi.org/10.7275/4akx-mw86 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2/1830 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ANGELS WHO STEPPED OUTSIDE THEIR HOUSES: “AMERICAN TRUE WOMANHOOD” AND NINETEENTH-CENTURY (TRANS)NATIONALISMS A Dissertation Presented By GAYATHRI MADHURANGI HEWAGAMA Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY February 2020 Department of English © Copyright by Gayathri Madhurangi Hewagama 2020 All Rights Reserved ANGELS WHO STEPPED OUTSIDE THEIR HOUSES: “AMERICAN TRUE WOMANHOOD” AND NINETEENTH-CENTURY (TRANS)NATIONALISMS A Dissertation Presented By GAYATHRI MADHURANGI HEWAGAMA Approved as to style and content by Nicholas K. Bromell, Chair Hoang G. Phan, Member Randall K. Knoper, Member Adam Dahl, Member Donna LeCourt, Acting Chair Department of English DEDICATION To my mother, who taught me my first word in English. -

Bayard Taylor and His Transatlantic Representations of Germany: a Nineteenth- Century American Encounter John Kemp

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository History ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations 7-12-2014 Bayard Taylor and his Transatlantic Representations of Germany: A Nineteenth- Century American Encounter John Kemp Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/hist_etds Recommended Citation Kemp, John. "Bayard Taylor and his Transatlantic Representations of Germany: A Nineteenth-Century American Encounter." (2014). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/hist_etds/38 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in History ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. John Stephan Kemp Candidate History Department This dissertation is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Dissertation Committee: Dr. Melissa Bokovoy , Chairperson Dr. Eliza Ferguson Dr. Margaret Connell-Szasz Dr. Peter White I BAYARD TAYLOR AND HIS TRANSATLANTIC REPRESENTATIONS OF GERMANY: A NINETEENTH-CENTURY AMERICAN ENCOUNTER BY JOHN STEPHAN KEMP B.A., History, University of New Mexico, 1987 M.A., Western World to 1500, University of New Mexico, 1992 DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy History The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico May, 2014 II DEDICATION In memory of Chuck Preston, my UNM English 102 instructor, who passed away in 1985 - his confidence in my ability kept me in college when I considered dropping out To My parents, John and Hilde Kemp, without whose unwavering support and encouragement I would have faltered long ago To My daughters, Josefa, Amy, and Emily, who are the lights of my life. -

From the Books of Laurence Hutton Pdf Free Download

FROM THE BOOKS OF LAURENCE HUTTON PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Laurence Hutton | 188 pages | 30 Jun 2007 | Kessinger Publishing | 9780548313053 | English | Whitefish MT, United States From The Books Of Laurence Hutton PDF Book The copy in the Paris Mint Hotel des Monnaies is without the gilded wreath which this copy possesses. Johnson's medical attendant, Mr. He was carried in great pomp, and with many porters and in many 'busses, to the Pantheon, in ; but with Marat he was "de-Pantheonized by order of the National Convention " a year or two later. Percy Fitzgerald. Johnson's family had a copy. Its existence does not appear to have been known to the sculptor of the medallion head of Curran on the monu- ment in St. Seite 48 - There is no blinking the fact that in Mr. It is, of course, possible that Spurzheim took a life-cast from Coleridge's face. John McCullough, the first of this galaxy of stars to quit the stage of life, was a man of strong and attractive personality, if not a great actor ; he had many admirers in his profession and many friends out of it. Just a moment while we sign you in to your Goodreads account. He gave, upon the sixty- second page of his book, a drawing of this mask in profile, and the face is certainly identical with the face in my collection. His friends Bendemann and Hiibner took a cast of his features as he lay. His frame was tall and wiry; his hazel eyes were sharp and penetrating; his nose was aquiline; his beard was short and crisp ; his mouth was firm and tender ; his bearing was courtly, unpreten- tious, and dignified. -

Nathaniel Hawthorne

NATHANIEL HAWTHORNE THE CRITICAL HERITAGE Edited by J. DONALD CROWLEY London and New York Contents PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS page XV INTRODUCTION I NOTE ON THE TEXT 40 Fanshawe (1828, 1851) 1 Notice, New England Galaxy, 1828 41 2 SARAH JOSEPHA HALE, from a review, Ladies' Magazine, 1828 42 3 Notice, Yankee and Boston Literary Gazette, 1828 43 4 Notice [Boston] Bower of Taste, 1828 43 5 From an unsigned review, Boston Weekly Messenger, 1828 44 6 WILLIAM LEGGETT, from a review, Cri'ft'c, 1828 45 7 Hawthorne, from a letter to James T. Fields, 1851 47 The Token (1835-7) 8 PARK BENJAMIN, from a review, New-England Magazine, 1835 , 48 9 HENRY F. CHORLEY, from a review, Athenaeum, 1835 49 10 PARK BENJAMIN, from a review, American Monthly Magazine, 50 1836 11 LEWIS GAYLORD CLARK, from a review, Knickerbocker Magazine, 1837 , 52 Twice-Told Tales (1837-8) 12 Unsigned review, Salem Gazette, 1837 53 13 From an unsigned review, Knickerbocker Magazine, 1837 54 14 HENRY WADSWORTH LONGFELLOW, from a review, North American Review, 1837 55 15 Notice, Family Magazine, 1837 60 16 CHARLES FENNO HOFFMAN, review, American Monthly Magazine, 1838 60 17 ANDREW PRESTON PEABODY, from a review, Christian Examiner, 1838 64 vii HAWTHORNE The Gentle Boy; a Thrice-Told Tale (1839) 18 Hawthorne, from the Preface, 1839 page 68 19 Notice, New York Review, 1839 69 20 Notice, Literary Gazette, 1839 69 Grandfather's Chair (1841-3) 21 Hawthorne, Preface, 1841 70 22 Notice, Athenaeum, 1842 71 23 JAMES RUSSELL LOWELL, from a review of Historical Tales for Youth, Pioneer, 1843 72 24 E.