THE Chap-Book SEMI-MONTHLY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Maryland Historical Magazine, 1941, Volume 36, Issue No. 1

ma SC 5Z2I~]~J41 MARYLAND HISTORICAL MAGAZINE PUBLISHED UNDER THE AUTHORITY OF THE MARYLAND HISTORICAL SOCIETY VOLUME XXXVI BALTIMORE 1941 CONTENTS OF VOLUME XXXVI PAGE THE SUSQUEHANNOCK FORT ON PISCATAWAY CREEK. By Alice L. L. Ferguson, 1 ELIZA GODBFROY: DESTINY'S FOOTBALL. By William D. Hoyt, Jr., ... 10 BLUE AND GRAY: I. A BALTIMORE VOLUNTEER OF 1864. By William H. fames, 22 II. THE CONFEDERATE RAID ON CUMBERLAND, 1865. By Basil William Spalding, 33 THE " NARRATIVE " OF COLONEL JAMES RIGBIE. By Henry Chandlee Vorman, . 39 A WEDDING OF 1841, 50 THE LIFE OF RICHARD MALCOLM JOHNSTON IN MARYLAND, 1867-1898. By Prawds Taylor Long, concluded, 54 LETTERS OF CHARLES CARROLL, BARRISTER, continued, 70, 336 BOOK REVIEWS, 74, 223, 345, 440 NOTES AND QUERIES, 88, 231, 354, 451 PROCEEDINGS OF THE SOCIETY, 90, 237, 455 LIST OF MEMBERS, 101 THE REVOLUTIONARY IMPULSE IN MARYLAND. By Charles A. Barker, . 125 WILLIAM GODDARD'S VICTORY FOR THE FREEDOM OF THE PRESS. By W. Bird Terwilliger, 139 CONTROL OF THE BALTIMORE PRESS DURING THE CIVIL WAR. By Sidney T. Matthews, 150 SHIP-BUILDING ON THE CHESAPEAKE: RECOLLECTIONS OF ROBERT DAWSON LAMBDIN, 171 READING INTERESTS OF THE PROFESSIONAL CLASSES IN COLONIAL MARYLAND, 1700-1776. By Joseph Towne Wheeler, 184, 281 THE HAYNIE LETTERS 202 BALTIMORE COUNTY LAND RECORDS OF 1687. By Louis Dow Scisco, . 215 A LETTER FROM THE SPRINGS, 220 POLITICS IN MARYLAND DURING THE CIVIL WAR. By Charles Branch Clark, . 239 THE ORIGIN OF THE RING TOURNAMENT IN THE UNITED STATES. By G. Harrison Orians, 263 RECOLLECTIONS OF BROOKLANDWOOD TOURNAMENTS. By D. Sterett Gittings, 278 THE WARDEN PAPERS. -

2006 July-August

July-August 2006 NEWSBOY Page 1 VOLUME XLIV JULY-AUGUST 2006 NUMBER 4 An Alger trio Part Two: Horatio Alger, Jr., John Townsend Trowbridge and Louise Chandler Moulton -- See Page 7 Carl Hartmann The Horatio Alger Society’s ‘Most Valuable Player’ An 1898 letter from Horatio Alger to Louise Chandler Moulton. From the J.T. Trowbridge papers, Department of Manuscripts, Houghton Library, Harvard University. Permission acknowledgement on Page 7. A previously unpublished story -- See Page 3 by renowned author Capwell Wyckoff: Drumbeat at Trenton Photo courtesy of Bernie Biberdorf, 1991 -- See Page 15 Page 2 NEWSBOY July-August 2006 1234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012123456789 1234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012123456789 1234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012123456789 1234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012123456789 HORATIO ALGER SOCIETY 1234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012123456789 1234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012123456789 1234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012123456789 1234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012123456789 To further the philosophy of Horatio Alger, Jr. and to encourage the 1234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012123456789 1234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012123456789 1234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012123456789 spirit of Strive and Succeed -

Babylon Revisited Rare Books & Yesterday's Gallery Catalog 68

Babylon Revisited Rare Books & Yesterday's Gallery yesterdaysgallery .com PO Box 154 / E. Woodstock, CT 06244 860-928-1216 / [email protected] Catalog 68 Please confirm the availability of your choices before submitting payment. All items are subject to prior sale. You may confirm your order by telephone, email or mail. We accept the following payment methods: Visa, Mastercard, Paypal, Personal Checks, Bank Checks, International and Postal Money Orders. Connecticut residents must add 6% sales tax. All items are guaranteed as described and may be returned for any reason. Please notify us within three days of receipt and note the reason for the return. All items should be shipped fully insured. Shipping charges are $6.00 for the first item, $1.50 for each additional item. Shipping of sets or unusual items or items being sent overseas will be billed at cost. We generally ship via the U. S. Postal Service. 1) ABBE, George. Voices in the Square. New York: Coward-McCann. 1938. First Edition. Earle dustjacket art. Author's first novel and story of a New England town. Near Fine in Very Good plus dustjacket, some rubbing to spine ends and flap corners, few nicks. $125.00 2) ANONYMOUS. One Woman's War. New York: Macaulay Company. 1930. First Edition. Stylized dustjacket art. Uncommon World War One themed narrative from a woman's point of view. From the jacket copy: "Some of the women war workers never returned; some returned to commit suicide rather than face the memory of what they had become. The woman who writes this book was a member of an aristocratic family. -

Short Poetry Collection 80

Short Poetry Collection 80 1. Annabel Lee by Edgar Allan Poe (1809-1849), read by David Duckett 2. Azure and Gold by Amy Lowell (1874-1925), read by ravenotation 3. A Burnt Ship by John Donne (1572-1631), read by Shawn Craig Smith 4. By the Candelabra's Glare by L. Frank Baum (1856-1919), read by Miriam Esther Goldman 5. The Children by Rudyard Kipling (1865-1936), read by Ruth Golding 6. Composed upon Westminster Bridge by William Wordsworth (1770-1840), read by Jhiu 80 Collection Short Poetry 7. Corporal Stare by Robert Graves (1895-1985), read by ravenotation 8. The Crucifixion of Eros by Clark Ashton Smith (1893-1961), read by Peter Piazza 9. Darkness by Lord Byron (1778-1824), read by Sergio Baldelli 10. The Death of the Hired Man by Robert Frost (1874-1963), read by Nicholas Clifford 11. Dubiety by Robert Browning (1812-1889), read by E. H. Blackmore 12. Dulce Et Decorum Est by Wilfrid Owen (1893-1918), read by Bellona Times 13. Epilogue by Robert Browning (1812-1889), read by E. H. Blackmore 14. How a Cat Was Annoyed and by Guy Wetmore Carryl (1873-1904), read by Bellona Times 15. The Ideal by Francis S. Saltus (1849-1889), read by Floyd Wilde 16. I Find No Peace by Thomas Wyatt (1503-1542), read by Jhiu 17. The Indian's Welcome to the Pilgrim Fathers by Lydia H. Sigourney (1791-1865), read by Jim Fish 18. Louisa M. Alcott In Memoriam by Louise Chandler Moulton (1835-1908), read by Carolyn Frances 19. The Marshes of Glynn by Sidney Lanier (1842-1881), read by SilverG 20. -

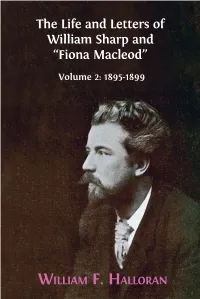

Fiona Macleod”

The Life and Letters of William Sharp and “Fiona Macleod” Volume 2: 1895-1899 W The Life and Letters of ILLIAM WILLIAM F. HALLORAN William Sharp and What an achievement! It is a major work. The lett ers taken together with the excellent H F. introductory secti ons - so balanced and judicious and informati ve - what emerges is an amazing picture of William Sharp the man and the writer which explores just how “Fiona Macleod” fascinati ng a fi gure he is. Clearly a major reassessment is due and this book could make it ALLORAN happen. Volume 2: 1895-1899 —Andrew Hook, Emeritus Bradley Professor of English and American Literature, Glasgow University William Sharp (1855-1905) conducted one of the most audacious literary decep� ons of his or any � me. Sharp was a Sco� sh poet, novelist, biographer and editor who in 1893 began The Life and Letters of William Sharp to write cri� cally and commercially successful books under the name Fiona Macleod. This was far more than just a pseudonym: he corresponded as Macleod, enlis� ng his sister to provide the handwri� ng and address, and for more than a decade “Fiona Macleod” duped not only the general public but such literary luminaries as William Butler Yeats and, in America, E. C. Stedman. and “Fiona Macleod” Sharp wrote “I feel another self within me now more than ever; it is as if I were possessed by a spirit who must speak out”. This three-volume collec� on brings together Sharp’s own correspondence – a fascina� ng trove in its own right, by a Victorian man of le� ers who was on in� mate terms with writers including Dante Gabriel Rosse� , Walter Pater, and George Meredith – and the Fiona Macleod le� ers, which bring to life Sharp’s intriguing “second self”. -

Report of the Librarian

216 American Antiquarian Society [Oct., REPORT OF THE LIBRARIAN "My library was dukedom large enough. " —Tempest, i:2 HEN Joseph's brethren came to his adopted W country during the seven lean years, they were made happy by discovering an abundance of food stored up for their need. And so it is with the historians and college professors from the far corners of the United States who flock to us all the year long, but especially during the summer vacation and the Christmas holidays, eager for our books and newspaper files, our manuscripts, maps and prints, for which they have hungered during the months when they had available only the less fortunately stored historical granaries of their various institutions. From Florida to Vancouver they have journeyed to Worcester in ever-increasing numbers to buy with their enthusiastic appreciation the rich grain of our histori- cal, biographical, and literary resources. As we watch them at their work, we cannot but share their enthu- siasm when they find here the varied materials they need for the scholarly work in which they are engaged. A Seventh Day Adventist historian from Washing- ton found our collections particularly rich in the rare periodicals, pamphlets, and broadsides relating to the Millerite delusion. A business historian was delighted with our wealth of editions of the early manuals of bookkeeping which he needed for his bibliography. A Yale graduate' student delved into our source material on the question of war guilt at the beginning of the Civil War. A Radcliffe graduate was made happy with an abundance of material on the practice of medicine in Colonial days. -

The Woman's Story, As Told by Twenty American Women;

i a 3= S 11 I |ai ^ <G133NV-SOV^ s I i I % ^OF-CA! c: S S > S oI = IS IVrz All ^ * a =? 01 I lOS-Af i | a IZB I VM vvlOSANGElfr;* ^F'CAI!FO% i i -n 5<-;> i 1 % s z S 1 1 O 11... iiim ^J O j f^i<L ^3AINlT3\\v s^lOSANCFlfx/ c 1 I I TV) I 3 l^L/I s ! s I THE WO MAN'S STORY AS TOLD BY TWENTY AMERICAN WOMEN PORTRAITS, AND SKETCHES OF THE AUTHORS BY LAURA C. HOLLOWAY " Author of The Ladies of the IVTiite House," "An Hour with " Charlotte Bronte," Adelaide Nvilson" "The Hiailh- stone," "Mothers of Great Men and Women," "Howard, the Christian Hero," "The Home in Poetry," etc. NEW YORK JOHN B. ALDEN, PUBLISHER 1889 Copyright, 1888, BT LAURA C. HOLLOWAY,, 607 CONTENTS. Preface v Harriet Beecher Stowe Portrait and Biographical Sketcli ix Uncle Lot. By Harriet Beecher Stowe 1 Prescott Portrait and ^Harriet Spofford. Biographical Sketch 33 Old Madame. By Harriet Prescott Spofford 37 Rebecca Harding Davis. Biographical Sketch 69 Tirar y Soult. By Rebecca Harding Davis 73 Edna Dean Proctor. Portrait and Biographical Sketcli. 97 Tom Foster's Wife. By Edna Dean Proctor 99 Marietta Holley. Portrait and Biographical Sketcli. .113 Fourth of July in Jonesville. By Marietta Holley. 115 Nora Perry. Portrait and Biographical Sketch 133 Dorothy. By Nora Perry 135 Augusta Evans Wilson. Portrait and Biographical Sketch 151 The Trial of Beryl. By Augusta Evans Wilson 157 Louise Chandler Moulton. Portrait and Biographical Sketch 243 * " Nan." By Louise Chandler Moulton 247 Celia Thaxter. -

"Across the Twilight Wave" : a Study of Meaning, Structure, and Technique

“ACROSS THE TWILIGHT WAVE”: A STUDY OF MEANING, STRUCTURE, AND TECHNIQUE IN MEREDITH’S MODERN LOVE By WILLIE DUANE READER A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE COUNCIL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA April, 1967 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to the many persons and Institutions which have assisted me in preparing this dissertation. Thanks are due to the libraries of the University of Florida, the Uni- versity of South Florida, the University of Texas, Harvard University, Yale University, Princeton University, and the Henry E. Huntington Library and Art Gallery, whose resources were made available to me, and to the librarians of these institutions for whose unfailing courtesy and patience I am grateful. An extra debt of gratitude is owed to Professor C. L. Cline of the University of Texas, who made available to me the resources of his per- sonal collection of Meredithiana, and who provided me with specialized information on Meredith which he had gathered while preparing a new edi- tion of Meredith's letters. A similar debt of gratitude is owed to Professor Phyllis Bartlett of Queens College, who provided me with informa- tion gathered while preparing a new edition of Meredith's poems. Finally, I would like to express my very great appreciation to the faculty members of the University of Florida who are members of the com- mittee which has guided me in the present work: Professors Ants Oras, William Ruff, and Leland L. Zimmerman. To Professor Oras I am especially grateful, both for his detailed supervision of this work and for his great kindness to me during several years of study at the University of Florida. -

Josiah J. Hawes

Wilson, “A Famous Photographer and his Sitters” (Josiah J. Hawes,) April 1898 (keywords: Josiah Johnson Hawes, Albert Sands Southworth, Rufus Rockwell Wilson, history of the daguerreotype, history of photography.) ————————————————————————————————————————————— THE DAGUERREOTYPE: AN ARCHIVE OF SOURCE TEXTS, GRAPHICS, AND EPHEMERA The research archive of Gary W. Ewer regarding the history of the daguerreotype http://www.daguerreotypearchive.org EWER ARCHIVE P8910001 ————————————————————————————————————————————— Published in: Demorest’s Family Magazine (New York) 34:5 (April 1898): 134–135, 156. A FAMOUS PHOTOGRAPHER AND HIS SITTERS. BY RUFUS ROCKWELL WILSON. HIGH above the noises of a great city, in the top story of one of the old buildings that girt Scollay Square, in Boston, there labors daily a man who is probably the oldest active photographer in the world. His name is Josiah Johnson Hawes. He was born in Sudbury, Massachusetts, February 20, 1808 and is consequently more than ninety years old. He received his education in the common schools, studied art, and painted miniatures, portraits and landscapes until 1841. He then became interested in the invention of Daguerre and, with Albert S. Southworth, made for many years the finest daguerreotypes and photographs in America. He has occupied his present studio for upward of half a century. In these rooms have posed hundreds of men and women whose fame time has already made secure. Charles Dickens used to drop in upon Mr. Hawes, and loved to spend a leisure hour in a place that was to him even then a curiosity shop. Phillips Brooks posed here only a few years before his death, and General Butler’s picture is one that Mr. -

Download the Discussion Guide for Little Women

WEDNESDAY, MAY 20 AT 3:00 PM OR THURSDAY, MAY 21 AT 6:30 PM DISCUSSION GUIDE: THE BEEKEEPER OF ALEPPO By Louisa May Alcott ABOUT THE AUTHOR Alcott was a daughter of noted Transcendentalist Amos Bronson Alcott and Abigail May Alcott. Louisa's father started the Temple School; her uncle, Samuel Joseph May, was a noted abolitionist. Though of New England parentage and residence, she was born in Germantown, which is currently part of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. She had three sisters: one elder (Anna Alcott Pratt) and two younger (Elizabeth Sewall Alcott and Abigail May Alcott Nieriker). The family moved to Boston in 1834 or 1835, where her father established an experimental school and joined the Transcendental Club with Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau. During her childhood and early adulthood, she shared her family's poverty and Transcendentalist ideals. In 1840, after several setbacks with the school, her family moved to a cottage on two acres along the Sudbury River in Concord, Massachusetts. The Alcott family moved to the Utopian Fruitlands community for a brief interval in 1843-1844 and then, after its collapse, to rented rooms and finally to a house in Concord purchased with her mother's inheritance and help from Emerson. Alcott's early education had included lessons from the naturalist Henry David Thoreau but had chiefly been in the hands of her father. She also received some instruction from writers and educators such as Ralph Waldo Emerson, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Margaret Fuller, who were all family friends. She later described these early years in a newspaper sketch entitled "Transcendental Wild Oats," afterwards reprinted in the volume Silver Pitchers (1876), which relates the experiences of her family during their experiment in "plain living and high thinking" at Fruitlands. -

Carlyle's Laugh, and Other Surprises

Cbomac iyrntruovt!) I)ig;crin0on WORKS. Newly arranged, yvols. iamo, each, $2.00. 1. CHEERFUL YESTERDAYS. 2. CONTEMPORARIES. 3. ARMY LIFE IN A BLACK REGIMENT. 4. WOMEN AND THE ALPHABET. 5. STUDIES IN ROMANCE. 6. OUTDOOR STUDIES; AND POEMS. 7. STUDIES IN HISTORY AND LETTERS. THE PROCESSION OF THE FLOWERS. $1.25. THE AFTERNOON LANDSCAPE. Poems and Translations. $1.00. THE MONARCH OF DREAMS. i8mo, 50 cents. MARGARET FULLER OSSOLI. In the American Men of Letters Series. i6mo, $1.50. HENRY W. LONGFELLOW. In American Men of Letters Series. i6mo, $1.10, net. Postage 10 cents. PART OF A MAN S LIFE. Illustrated. Large 8vo, $2.50, net. Postage 18 cents. LIFE AND TIMES OF STEPHEN HIGGINSON. Illustrated. Large crown 8vo, $2.00, net. Postage extra. CARLYLE S LAUGH AND OTHER SURPRISES. i2mo, $2.00, net. Postage 15 cents. EDITED WITH MRS. E. H. BIGELOW. AMERICAN SONNETS. i8mo, $1.25. HOUGHTON MIFFLIN COMPANY BOSTON AND NEW YORK CARLYLE S LAUGH AND OTHER SURPRISES CARLYLE S LAUGH AND OTHER SURPRISES BY THOMAS WENTWORTH HIGGINSON BOSTON AND NEW YORK HOUGHTON MIFFLIN COMPANY (fce Ctitersibe preii? Cambridge MDCCCCIX COPYRIGHT, 1909, BY THOMAS WENTWORTH HIGGINSON ALL RIGHTS RESERVED Published October IQOQ 1-/3 NOTE THE two papers in this volume which bear the " titles " A Keats Manuscript and " A Shelley " Manuscript are reprinted by permission from " a work called Book and Heart," by Thomas Wentworth Higginson, copyright, 1897, by Harper and Brothers, with whose consent the essay entitled "One of Thackeray s Women" also is published. -

From the Library Of…

From the Library of….. Association Copies, offered by Up-County Letters, Gardnerville, Nevada From the Library of….. Item 32 Association Copies Item 32 Mark Stirling, Up-Country Letters. PO Box 596, Gardnerville, NV 89410 530 318-4787 (cell); 775 392-1122 (land line) [email protected] Front cover: Items 10, 39 www.upcole.com Alcott, Louisa May - 1 Huth, Alfred Henry - 58 Arnold, Matthew - 58 Huth, Henry - 58, 62 Atkinson, J. Brooks - 51 James, Henry - 25, 49 Babbitt, Irving - 35 Jeffers, Robinson - 26 Barings Bank - 39 Jones, Samuel Arthur - 61 Barth, John - 2 thru 9 Judd, Sylvester - 26 Beebe, Charles William - 59 Kant, Immanuel - 24 Bennett, Melba - 25 Kirgate Press - 61 Benson, Joseph - 21 Lang, Andrew - 25 Bradford, George P. - 10 Lessing, Gotthold - 36 Bristed, Charles - 11 Lindsay Swift - 40 Brook Farm - 14, 15, 38, 40 Longfellow, Henry Wadsworth - 28, 29, 55 Brooks, Van Wyck - 41 thru 53 Lowell, Charles - 30 Buckle, Henry Thomas - 58 Lowell, James Russell - 17, 30, 31, 57 Carlyle, Thomas - 14, 31, 61, 62 Marquez, Gabriel Garcia, 3 Carpenter, Frederic Ives - 18 Martin, Maud de Lorme- 60 Chamberlain, Houston Stewart - 24 Miller, DeWitt - 61 Channing, William Ellery - 12 Mississippi River - 32 Channning, William Henry - 12 Mitau, Marjorie - 59, 60 Charles Eliot Norton - 57 Mitau, Martin - 59, 60 Codman, John Thomas - 38 Munro, Alice - 4, 5 Concord, Mass. - 1, 10 Niagara Falls - 29 Curtis, George William - 15, 22, 57 Paine, Cornelius - 62 Da Vinci, Leonardo - 24 Parker, Theodore - 17, 58 Dana, Richard Henry - 39 Patmore, Coventry - 33, 34 Darwin, Charles - 58 Payson, George - 32 Descartes - 24 Plato - 24 Dodge, Mary Mapes - 13 Rantoul, Robert - 40 Doheny, Estelle - 56 Raven, Ralph - 32 Duncan, Rebecca L.