Josiah J. Hawes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE Chap-Book SEMI-MONTHLY

DELOS AVERY 425 SURF ST. CHICAGO iiiii'iCJS HSSTQR5CAL SUkVcV THE Chap- Book A MISCELLANY of Curious and Interesting Songs, Ballads, Tales, Histories, &c. ; adorned with a variety of pictures and very delightful to read ; newly composed by MANY CELEBRATED WRITERS; To which are annexM a LARGE COLLECTION of Notices of BOOKS. VOLUME L From May i^ib to November 1st A.D. MDCCCXC IV CHICAGO Printed for Stone &' Kimball o^ the Caxton Building where Shopkeepers^ Hawkersy and others are supplied DELOS AVERY 42S SURF ST. CHICAGO CKAB 1 INDEX TO VOLUME I POETRY ALDRICH, THOMAS BAILEY page ORIGINALITY 247 PESSIMISTIC POETS I03 BROWN, ALICE TRILBY 91 CARMAN, BLISS NANCIBEL 103 THE PRAYER IN THE ROSE GARDEN 34 CRAM, RALPH ADAMS THE RIDE OF THE CLANS I39 GOETZ, P. B. QUATRAINS 344 HALL, GERTRUDE MOONLIGHT, TRANSLATED FROM PAUL VERLAINE 7 VERSES 184 HENDERSON, W. J. ASPIRATION 335 HOVEY, RICHARD HUNTING SONG 253 THE SHADOWS KIMBALL, HANNAH PARKER PURITY 223 MOODY, WILLIAM VAUGHN A BALLADE OF DEATH-BEDS 5I MORRIS, HARRISON S. PARABLE 166 00 MOULTON, LOUISE CHANDLER page IN HELEN'S LOOK I96 WHO KNOWS? 27 MUNN, GEORGE FREDERICK THE ENCHANTED CITY 1 27 PARKER, GILBERT THERE IS AN ORCHARD 331 PEABODY, JOSEPHINE PRESTON THE WOMAN OF THREE SORROWS I34 ROBERTS, CHARLES G. D. THE UNSLEEPING 3 SCOLLARD, CLINTON THE WALK 183 SHARP, WILLIAM TO EDMUND CLARENCE STEDMAN 212 TAYLOR, J. RUSSELL THE NIGHT RAIN I27 VERLAINE, PAUL EPIGRAMMES 211 MOONLIGHT, TRANSLATED BY GERTRUDE HALL 7I YELLOW BOOK-MAKER, THE 4I PROSE ANNOUNCEMENTS I9, 43, 73, 96, I18, I47, I75, 204, 242, 266, 357 B. -

2006 July-August

July-August 2006 NEWSBOY Page 1 VOLUME XLIV JULY-AUGUST 2006 NUMBER 4 An Alger trio Part Two: Horatio Alger, Jr., John Townsend Trowbridge and Louise Chandler Moulton -- See Page 7 Carl Hartmann The Horatio Alger Society’s ‘Most Valuable Player’ An 1898 letter from Horatio Alger to Louise Chandler Moulton. From the J.T. Trowbridge papers, Department of Manuscripts, Houghton Library, Harvard University. Permission acknowledgement on Page 7. A previously unpublished story -- See Page 3 by renowned author Capwell Wyckoff: Drumbeat at Trenton Photo courtesy of Bernie Biberdorf, 1991 -- See Page 15 Page 2 NEWSBOY July-August 2006 1234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012123456789 1234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012123456789 1234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012123456789 1234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012123456789 HORATIO ALGER SOCIETY 1234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012123456789 1234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012123456789 1234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012123456789 1234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012123456789 To further the philosophy of Horatio Alger, Jr. and to encourage the 1234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012123456789 1234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012123456789 1234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012123456789 spirit of Strive and Succeed -

Babylon Revisited Rare Books & Yesterday's Gallery Catalog 68

Babylon Revisited Rare Books & Yesterday's Gallery yesterdaysgallery .com PO Box 154 / E. Woodstock, CT 06244 860-928-1216 / [email protected] Catalog 68 Please confirm the availability of your choices before submitting payment. All items are subject to prior sale. You may confirm your order by telephone, email or mail. We accept the following payment methods: Visa, Mastercard, Paypal, Personal Checks, Bank Checks, International and Postal Money Orders. Connecticut residents must add 6% sales tax. All items are guaranteed as described and may be returned for any reason. Please notify us within three days of receipt and note the reason for the return. All items should be shipped fully insured. Shipping charges are $6.00 for the first item, $1.50 for each additional item. Shipping of sets or unusual items or items being sent overseas will be billed at cost. We generally ship via the U. S. Postal Service. 1) ABBE, George. Voices in the Square. New York: Coward-McCann. 1938. First Edition. Earle dustjacket art. Author's first novel and story of a New England town. Near Fine in Very Good plus dustjacket, some rubbing to spine ends and flap corners, few nicks. $125.00 2) ANONYMOUS. One Woman's War. New York: Macaulay Company. 1930. First Edition. Stylized dustjacket art. Uncommon World War One themed narrative from a woman's point of view. From the jacket copy: "Some of the women war workers never returned; some returned to commit suicide rather than face the memory of what they had become. The woman who writes this book was a member of an aristocratic family. -

Short Poetry Collection 80

Short Poetry Collection 80 1. Annabel Lee by Edgar Allan Poe (1809-1849), read by David Duckett 2. Azure and Gold by Amy Lowell (1874-1925), read by ravenotation 3. A Burnt Ship by John Donne (1572-1631), read by Shawn Craig Smith 4. By the Candelabra's Glare by L. Frank Baum (1856-1919), read by Miriam Esther Goldman 5. The Children by Rudyard Kipling (1865-1936), read by Ruth Golding 6. Composed upon Westminster Bridge by William Wordsworth (1770-1840), read by Jhiu 80 Collection Short Poetry 7. Corporal Stare by Robert Graves (1895-1985), read by ravenotation 8. The Crucifixion of Eros by Clark Ashton Smith (1893-1961), read by Peter Piazza 9. Darkness by Lord Byron (1778-1824), read by Sergio Baldelli 10. The Death of the Hired Man by Robert Frost (1874-1963), read by Nicholas Clifford 11. Dubiety by Robert Browning (1812-1889), read by E. H. Blackmore 12. Dulce Et Decorum Est by Wilfrid Owen (1893-1918), read by Bellona Times 13. Epilogue by Robert Browning (1812-1889), read by E. H. Blackmore 14. How a Cat Was Annoyed and by Guy Wetmore Carryl (1873-1904), read by Bellona Times 15. The Ideal by Francis S. Saltus (1849-1889), read by Floyd Wilde 16. I Find No Peace by Thomas Wyatt (1503-1542), read by Jhiu 17. The Indian's Welcome to the Pilgrim Fathers by Lydia H. Sigourney (1791-1865), read by Jim Fish 18. Louisa M. Alcott In Memoriam by Louise Chandler Moulton (1835-1908), read by Carolyn Frances 19. The Marshes of Glynn by Sidney Lanier (1842-1881), read by SilverG 20. -

Report of the Librarian

216 American Antiquarian Society [Oct., REPORT OF THE LIBRARIAN "My library was dukedom large enough. " —Tempest, i:2 HEN Joseph's brethren came to his adopted W country during the seven lean years, they were made happy by discovering an abundance of food stored up for their need. And so it is with the historians and college professors from the far corners of the United States who flock to us all the year long, but especially during the summer vacation and the Christmas holidays, eager for our books and newspaper files, our manuscripts, maps and prints, for which they have hungered during the months when they had available only the less fortunately stored historical granaries of their various institutions. From Florida to Vancouver they have journeyed to Worcester in ever-increasing numbers to buy with their enthusiastic appreciation the rich grain of our histori- cal, biographical, and literary resources. As we watch them at their work, we cannot but share their enthu- siasm when they find here the varied materials they need for the scholarly work in which they are engaged. A Seventh Day Adventist historian from Washing- ton found our collections particularly rich in the rare periodicals, pamphlets, and broadsides relating to the Millerite delusion. A business historian was delighted with our wealth of editions of the early manuals of bookkeeping which he needed for his bibliography. A Yale graduate' student delved into our source material on the question of war guilt at the beginning of the Civil War. A Radcliffe graduate was made happy with an abundance of material on the practice of medicine in Colonial days. -

The Woman's Story, As Told by Twenty American Women;

i a 3= S 11 I |ai ^ <G133NV-SOV^ s I i I % ^OF-CA! c: S S > S oI = IS IVrz All ^ * a =? 01 I lOS-Af i | a IZB I VM vvlOSANGElfr;* ^F'CAI!FO% i i -n 5<-;> i 1 % s z S 1 1 O 11... iiim ^J O j f^i<L ^3AINlT3\\v s^lOSANCFlfx/ c 1 I I TV) I 3 l^L/I s ! s I THE WO MAN'S STORY AS TOLD BY TWENTY AMERICAN WOMEN PORTRAITS, AND SKETCHES OF THE AUTHORS BY LAURA C. HOLLOWAY " Author of The Ladies of the IVTiite House," "An Hour with " Charlotte Bronte," Adelaide Nvilson" "The Hiailh- stone," "Mothers of Great Men and Women," "Howard, the Christian Hero," "The Home in Poetry," etc. NEW YORK JOHN B. ALDEN, PUBLISHER 1889 Copyright, 1888, BT LAURA C. HOLLOWAY,, 607 CONTENTS. Preface v Harriet Beecher Stowe Portrait and Biographical Sketcli ix Uncle Lot. By Harriet Beecher Stowe 1 Prescott Portrait and ^Harriet Spofford. Biographical Sketch 33 Old Madame. By Harriet Prescott Spofford 37 Rebecca Harding Davis. Biographical Sketch 69 Tirar y Soult. By Rebecca Harding Davis 73 Edna Dean Proctor. Portrait and Biographical Sketcli. 97 Tom Foster's Wife. By Edna Dean Proctor 99 Marietta Holley. Portrait and Biographical Sketcli. .113 Fourth of July in Jonesville. By Marietta Holley. 115 Nora Perry. Portrait and Biographical Sketch 133 Dorothy. By Nora Perry 135 Augusta Evans Wilson. Portrait and Biographical Sketch 151 The Trial of Beryl. By Augusta Evans Wilson 157 Louise Chandler Moulton. Portrait and Biographical Sketch 243 * " Nan." By Louise Chandler Moulton 247 Celia Thaxter. -

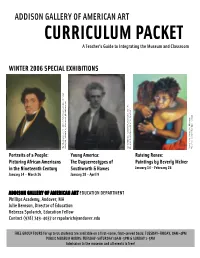

CURRICULUM PACKET a Teacher’S Guide to Integrating the Museum and Classroom

ADDISON GALLERY OF AMERICAN ART CURRICULUM PACKET A Teacher’s Guide to Integrating the Museum and Classroom WINTER 2006 SPECIAL EXHIBITIONS , 1815, oil on panel, s William Vareika f arles Jone h ca. 1850-1855, ft o i New York Portrait of C y, erican Art, g ller a nt G ry of Am e George Eastman House Collection 2005, Oil on canvas, of K y Reverand Rollin Heber Neale, Embrace, ourtes C eenwood, (1779 - 1856), , Hawes, r Iver, . c n 6 i 3 outhworth & 8 in. x Ethan Allen G 26 x 18 3/4 in., Addison Galle S Whole plate daguerreotype, ©Beverly M 4 Portraits of a People: Young America: Raising Renee: Picturing African Americans The Daguerreotypes of Paintings by Beverly McIver in the Nineteenth Century Southworth & Hawes January 14 – February 26 January 14 – March 26 January 28 – April 9 ADDISON GALLERY OF AMERICAN ART EDUCATION DEPARTMENT Phillips Academy, Andover, MA Julie Bernson, Director of Education Rebecca Spolarich, Education Fellow Contact (978) 749-4037 or [email protected] FREE GROUP TOURS for up to 55 students are available on a first-come, first-served basis: TUESDAY-FRIDAY, 8AM-4PM PUBLIC MUSEUM HOURS: TUESDAY-SATURDAY 10AM-5PM & SUNDAY 1-5PM Admission to the museum and all events is free! Exploring the Exhibitions This winter the Addison Gallery presents three special exhibitions which each speak to the enduring powers of portraiture and identity in unique ways: x Portraits of a People: Picturing African Americans in the Nineteenth Century x Young America: The Daguerreotypes of Southworth & Hawes x Raising Renee: Paintings by Beverly McIver Individually the exhibitions express the various ways that Americans have chosen to portray themselves over time. -

The Techniques and Material Aesthetics of the Daguerreotype

The Techniques and Material Aesthetics of the Daguerreotype Michael A. Robinson Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Photographic History Photographic History Research Centre De Montfort University Leicester Supervisors: Dr. Kelley Wilder and Stephen Brown March 2017 Robinson: The Techniques and Material Aesthetics of the Daguerreotype For Grania Grace ii Robinson: The Techniques and Material Aesthetics of the Daguerreotype Abstract This thesis explains why daguerreotypes look the way they do. It does this by retracing the pathway of discovery and innovation described in historical accounts, and combining this historical research with artisanal, tacit, and causal knowledge gained from synthesizing new daguerreotypes in the laboratory. Admired for its astonishing clarity and holographic tones, each daguerreotype contains a unique material story about the process of its creation. Clues from the historical record that report improvements in the art are tested in practice to explicitly understand the cause for effects described in texts and observed in historic images. This approach raises awareness of the materiality of the daguerreotype as an image, and the materiality of the daguerreotype as a process. The structure of this thesis is determined by the techniques and materials of the daguerreotype in the order of practice related to improvements in speed, tone and spectral sensitivity, which were the prime motivation for advancements. Chapters are devoted to the silver plate, iodine sensitizing, halogen acceleration, and optics and their contribution toward image quality is revealed. The evolution of the lens is explained using some of the oldest cameras extant. Daguerre’s discovery of the latent image is presented as the result of tacit experience rather than fortunate accident. -

"Across the Twilight Wave" : a Study of Meaning, Structure, and Technique

“ACROSS THE TWILIGHT WAVE”: A STUDY OF MEANING, STRUCTURE, AND TECHNIQUE IN MEREDITH’S MODERN LOVE By WILLIE DUANE READER A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE COUNCIL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA April, 1967 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to the many persons and Institutions which have assisted me in preparing this dissertation. Thanks are due to the libraries of the University of Florida, the Uni- versity of South Florida, the University of Texas, Harvard University, Yale University, Princeton University, and the Henry E. Huntington Library and Art Gallery, whose resources were made available to me, and to the librarians of these institutions for whose unfailing courtesy and patience I am grateful. An extra debt of gratitude is owed to Professor C. L. Cline of the University of Texas, who made available to me the resources of his per- sonal collection of Meredithiana, and who provided me with specialized information on Meredith which he had gathered while preparing a new edi- tion of Meredith's letters. A similar debt of gratitude is owed to Professor Phyllis Bartlett of Queens College, who provided me with informa- tion gathered while preparing a new edition of Meredith's poems. Finally, I would like to express my very great appreciation to the faculty members of the University of Florida who are members of the com- mittee which has guided me in the present work: Professors Ants Oras, William Ruff, and Leland L. Zimmerman. To Professor Oras I am especially grateful, both for his detailed supervision of this work and for his great kindness to me during several years of study at the University of Florida. -

Download the Discussion Guide for Little Women

WEDNESDAY, MAY 20 AT 3:00 PM OR THURSDAY, MAY 21 AT 6:30 PM DISCUSSION GUIDE: THE BEEKEEPER OF ALEPPO By Louisa May Alcott ABOUT THE AUTHOR Alcott was a daughter of noted Transcendentalist Amos Bronson Alcott and Abigail May Alcott. Louisa's father started the Temple School; her uncle, Samuel Joseph May, was a noted abolitionist. Though of New England parentage and residence, she was born in Germantown, which is currently part of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. She had three sisters: one elder (Anna Alcott Pratt) and two younger (Elizabeth Sewall Alcott and Abigail May Alcott Nieriker). The family moved to Boston in 1834 or 1835, where her father established an experimental school and joined the Transcendental Club with Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau. During her childhood and early adulthood, she shared her family's poverty and Transcendentalist ideals. In 1840, after several setbacks with the school, her family moved to a cottage on two acres along the Sudbury River in Concord, Massachusetts. The Alcott family moved to the Utopian Fruitlands community for a brief interval in 1843-1844 and then, after its collapse, to rented rooms and finally to a house in Concord purchased with her mother's inheritance and help from Emerson. Alcott's early education had included lessons from the naturalist Henry David Thoreau but had chiefly been in the hands of her father. She also received some instruction from writers and educators such as Ralph Waldo Emerson, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Margaret Fuller, who were all family friends. She later described these early years in a newspaper sketch entitled "Transcendental Wild Oats," afterwards reprinted in the volume Silver Pitchers (1876), which relates the experiences of her family during their experiment in "plain living and high thinking" at Fruitlands. -

Notable and Notorious: Historically Interesting People from the Last Green Valley

Notable and Notorious Historically interesting people from The Last Green Valley NATIONAL HERITAGE CORRIDOR www.thelastgreenvalley.org This project has been generously supported by the Connecticut East Regional Tourism District CHARACTERS BY NAME Click link to view Notable & Notorious A H P A Selection of Historical Characters from John Capen “Grizzly” Adams ....... 10 Nathan Hale ............................... 27 Captain Chauncey Paul ............... 24 Dr. Harry Ardell Allard ................ 62 Ann Hall ..................................... 59 Dr. Elisha Perkins ........................ 85 The Last Green Valley, a National Heritage Corridor Anshei Israel Congregation......... 78 Benjamin Hanks ......................... 36 Sarah Perkins ............................. 55 www.thelastgreenvalley.org Benedict Arnold ......................... 21 John Hartshorne ........................ 55 George Dennison Prentice .......... 63 James S. Atwood ........................ 42 William Lincoln Higgins ............. 11 Israel Putnam ............................. 26 Samuel Huntington .................... 33 CONTENTS B R Characters listed by last name ............................................ 5 William Barrows ......................... 47 I Alice Ramsdell ............................ 16 Characters listed by town ..................................................... 6 Clara Barton ............................... 73 Benoni Irwin .............................. 54 The Ray Family ........................... 14 A Brief History of The Last Green Valley -

Gold Clarioni

T210B SALE—Old papers, whole and dean. August Mtgazlnts. Jj at Khnnbiiku JouunaL olioe, 'prioe faitg '§ttmtbu fsurwt IS cts. ix?rhunrired. taulWtf 100 feet best lAOlt WALE—About quality ft JUMBO! * McClure's Safe, Sure, Magazine JD iron feuoe, with as new, suituble posts, good Ckwtm or hiam*. obituabt for lot or front of private residence. koticta, r». for • piece to cemetery yard OMIT'OW* or HKMFW-r, will August supplies companion Speedy. A Beautiful pattern at one third of cost. John L. ----O--——— are., be charged of life in Simple, remedy at the rate of ten cent* per lir a. Mr. Hamlin Garland's Ho description Stevens, AutfUBtu, Me. thara^•* _june&dtf lew than live cents. tbe steel mines at Homestead, in combines all these char- seventy published that on north Abf. ADVKKTINIgri AKKtniKCBirraTS de- V7IOB SALE—Alarge house lot the; or r> the June number, in a no less striking to T.Homas XXuTaiwmkwtv, whoae Xj side of WeBtern avenue. Apply was a but our BREAD WINNER at object lathe raising ,, of coal is certain to be Jumbo great Elephant, pants will be at scription of life in the depths a acteristics JT Lynch._ may^dtf DM!Ill’C money charged the rate of lirtcen of cent# Hnc. Crane. A paper SALE-Several houses. Prices van ting are Great Bargains. The 240 lb. man who thinks he can’t mine, by Stephen nnllUM U AitVKETiHiau Noticm, news will i* Perrons for a $1.99 form, personal recollections, by S. II. Byers, very popular. F»Bfrom ;*900 upwards.