Teaching Ukrainian As a Non-Native Language to National Minorities in Ukraine: Challenges for Evidence-Based Educational Policies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Territorial Structure of the West-Ukrainian Region Settling System

Słupskie Prace Geograficzne 8 • 2011 Vasyl Dzhaman Yuriy Fedkovych National University Chernivtsi (Ukraine) TERRITORIAL STRUCTURE OF THE WEST-UKRAINIAN REGION SETTLING SYSTEM STRUKTURA TERYTORIALNA SYSTEMU ZASIEDLENIA NA TERYTORIUM ZACHODNIEJ UKRAINY Zarys treści : W artykule podjęto próbę charakterystyki elementów struktury terytorialnej sys- temu zasiedlenia Ukrainy Zachodniej. Określono zakres organizacji przestrzennej tego systemu, uwzględniając elementy społeczno-geograficzne zachodniego makroregionu Ukrainy. Na podstawie przeprowadzonych badań należy stwierdzić, że struktura terytorialna organizacji produkcji i rozmieszczenia ludności zachodniej Ukrainy na charakter radialno-koncentryczny, co jest optymalnym wariantem kompozycji przestrzennej układu społecznego regionu. Słowa kluczowe : system zaludnienia, Ukraina Zachodnia Key words : settling system, West Ukraine Problem Statement Improvement of territorial structure of settling systems is among the major prob- lems when it regards territorial organization of social-geographic complexes. Ac- tuality of the problem is evidenced by introducing of the Territory Planning and Building Act, Ukraine, of 20 April 2000, and the General Scheme of Ukrainian Ter- ritory Planning Act, Ukraine, of 7 February 2002, both Acts establishing legal and organizational bases for planning, cultivation and provision of stable progress in in- habited localities, development of industrial, social and engineering-transport infra- structure ( Territory Planning and Building ... 2002, General Scheme of Ukrainian Territory ... 2002). Initial Premises Need for improvement of territorial organization of productive forces on specific stages of development delineates a circle of problems that require scientific research. 27 When studying problems of settling in 50-70-ies of the 20 th century, national geo- graphical science focused the majority of its attention upon separate towns and cit- ies, in particular, upon limitation of population increase in big cities, and to active growth of mid and small-sized towns. -

Jewish Cemetries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine

Syracuse University SURFACE Religion College of Arts and Sciences 2005 Jewish Cemetries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine Samuel D. Gruber United States Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/rel Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Gruber, Samuel D., "Jewish Cemeteries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine" (2005). Full list of publications from School of Architecture. Paper 94. http://surface.syr.edu/arc/94 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts and Sciences at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Religion by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JEWISH CEMETERIES, SYNAGOGUES, AND MASS GRAVE SITES IN UKRAINE United States Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad 2005 UNITED STATES COMMISSION FOR THE PRESERVATION OF AMERICA’S HERITAGE ABROAD Warren L. Miller, Chairman McLean, VA Members: Ned Bandler August B. Pust Bridgewater, CT Euclid, OH Chaskel Besser Menno Ratzker New York, NY Monsey, NY Amy S. Epstein Harriet Rotter Pinellas Park, FL Bingham Farms, MI Edgar Gluck Lee Seeman Brooklyn, NY Great Neck, NY Phyllis Kaminsky Steven E. Some Potomac, MD Princeton, NJ Zvi Kestenbaum Irving Stolberg Brooklyn, NY New Haven, CT Daniel Lapin Ari Storch Mercer Island, WA Potomac, MD Gary J. Lavine Staff: Fayetteville, NY Jeffrey L. Farrow Michael B. Levy Executive Director Washington, DC Samuel Gruber Rachmiel -

1 Introduction

State Service of Geodesy, Cartography and Cadastre State Scientific Production Enterprise “Kartographia” TOPONYMIC GUIDELINES For map and other editors For international use Ukraine Kyiv “Kartographia” 2011 TOPONYMIC GUIDELINES FOR MAP AND OTHER EDITORS, FOR INTERNATIONAL USE UKRAINE State Service of Geodesy, Cartography and Cadastre State Scientific Production Enterprise “Kartographia” ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Prepared by Nina Syvak, Valerii Ponomarenko, Olha Khodzinska, Iryna Lakeichuk Scientific Consultant Iryna Rudenko Reviewed by Nataliia Kizilowa Translated by Olha Khodzinska Editor Lesia Veklych ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ © Kartographia, 2011 ISBN 978-966-475-839-7 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction ................................................................ 5 2 The Ukrainian Language............................................ 5 2.1 General Remarks.............................................. 5 2.2 The Ukrainian Alphabet and Romanization of the Ukrainian Alphabet ............................... 6 2.3 Pronunciation of Ukrainian Geographical Names............................................................... 9 2.4 Stress .............................................................. 11 3 Spelling Rules for the Ukrainian Geographical Names....................................................................... 11 4 Spelling of Generic Terms ....................................... 13 5 Place Names in Minority Languages -

Jewish Cemeteries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine

JEWISH CEMETERIES, SYNAGOGUES, AND MASS GRAVE SITES IN UKRAINE United States Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad 2005 UNITED STATES COMMISSION FOR THE PRESERVATION OF AMERICA’S HERITAGE ABROAD Warren L. Miller, Chairman McLean, VA Members: Ned Bandler August B. Pust Bridgewater, CT Euclid, OH Chaskel Besser Menno Ratzker New York, NY Monsey, NY Amy S. Epstein Harriet Rotter Pinellas Park, FL Bingham Farms, MI Edgar Gluck Lee Seeman Brooklyn, NY Great Neck, NY Phyllis Kaminsky Steven E. Some Potomac, MD Princeton, NJ Zvi Kestenbaum Irving Stolberg Brooklyn, NY New Haven, CT Daniel Lapin Ari Storch Mercer Island, WA Potomac, MD Gary J. Lavine Staff: Fayetteville, NY Jeffrey L. Farrow Michael B. Levy Executive Director Washington, DC Samuel Gruber Rachmiel Liberman Research Director Brookline, MA Katrina A. Krzysztofiak Laura Raybin Miller Program Manager Pembroke Pines, FL Patricia Hoglund Vincent Obsitnik Administrative Officer McLean, VA 888 17th Street, N.W., Suite 1160 Washington, DC 20006 Ph: ( 202) 254-3824 Fax: ( 202) 254-3934 E-mail: [email protected] May 30, 2005 Message from the Chairman One of the principal missions that United States law assigns the Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad is to identify and report on cemeteries, monuments, and historic buildings in Central and Eastern Europe associated with the cultural heritage of U.S. citizens, especially endangered sites. The Congress and the President were prompted to establish the Commission because of the special problem faced by Jewish sites in the region: The communities that had once cared for the properties were annihilated during the Holocaust. -

Ukraine's Quest for Mature Nation Statehood

Ukraine’s Quest for Mature Nation Statehood By Vlad Spanu Oct. 01, 2015 Content Historical background Ethnics Romanians in Ukraine Ethnics Ukrainians in Romania and in the Republic of Moldova From challenge to opportunity Romanians in Ukraine 10th century: Slavic tribes (Ulichs and Tivertsy) from the north, Romanians (Vlachs) from the west, as well as Turkic nomads (Pechenegs, Cumans and later Tatars) from the east Since 14th century, the area were intermittently ruled by Lithuanian dukes, Polish kings, Crimean khans, and Moldavian princes (Ion Vodă Armeanul) In 1681 Gheorghe Duca's title was "Despot of Moldavia and Ukraine,” as he was simultaneously Prince of Moldavia and Hetman of Ukraine Other Moldavian princes who held control of the territory in 17th and 18th centuries were Ştefan Movilă, Dimitrie Cantacuzino and Mihai Racoviţă Renown Romanians among Cossacks Among the hetmans of the Cossacks: -1593–1596: Ioan Potcoavă, Grigore Lobodă (Hryhoriy Loboda) - 1659–1660: Ioan Sârcu (Ivan Sirko) - 1727–1734: DăniLă ApostoL (DanyLo ApostoL) - Others hetmans: Alexander Potcoavă, Constantin Potcoavă, Petre Lungu, Petre Cazacu, Tihon Baibuza, Samoilă Chişcă, Opară, Trofim VoLoşanin, Ion ŞărpiLă, Timotei Sgură, Dumitru Hunu Other high-ranking Cossacks: Polkovnyks Toader Lobădă and Dumitraşcu Raicea in PereyasLav-KhmeLnytskyy, Martin Puşcariu in Poltava, BurLă in Gdańsk, PaveL Apostol in Mirgorod, Eremie Gânju and Dimitrie Băncescu in Uman, VarLam BuhăţeL, Grigore GămăLie in Lubensk, Grigore Cristofor, Ion Ursu, Petru Apostol in Lubensk -

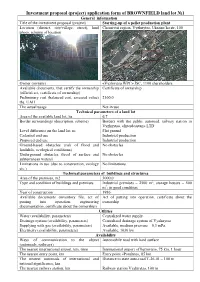

Investment Proposal (Project) Application Form of BROWNFIЕLD Land

Investment proposal (project) application form of BROWNFIЕLD land lot №1 General information Title of the investment proposal (project) Starting-up of a pellet production plant Location (district, city/village, street), land Chernivtsi region, Vyzhnytsa, Ukrains’ka str, 100 photo, scheme of location Owner (owners) «Vyzhnytsa WPC» JSC, 1100 shareholders Available documents, that certify the ownership Certificate of ownership (official act, certificate of ownership) Preliminary cost (balanced cost, assessed value) 2160,0 ths. UAH The actual usage Not in use Technical parameters of a land lot Area of the available land lot, ha 6,7 Border surroundings (description, scheme) Borders with the public autoroad, railway station in Vyzhnytsa, «Interdosstan» LTD Level difference on the land lot, m Flat ground Cadastral end use Industrial production Proposed end use Industrial production Ground-based obstacles (risk of flood and No obstacles landslide, ecological conditions) Underground obstacles (level of surface and No obstacles subterranean waters) Limitations in use (due to construction, ecology No limitations etc.) Technical parameters of buildings and structures Area of the premises, m2 3000,0 Type and condition of buildings and premises Industrial premises – 2500 m2, storage houses – 500 m2; in good condition Year of construction 1986 Available documents (inventory file, act of Act of putting into operation, certificate about the putting into operation, engineering ownership documentation, certificate about the ownership) Utilities Water (availability, -

«Made in Bukovyna»

ELECTRONIC GUIDE OF ENTREPRENEURSHIP ACTIVITY IN CHERNIVTSI REGION «MADE IN BUKOVYNA» 2018 Contents Electronics and machine building………………………………………………………..5 «ARTON» private enterprise……………………………………………………………………………….6 JSC «SKB Electronmash»…………………………………………………………………………………..7 «Sokyrianskyi Mashynobudivnyi Zavod» ALC…………………………………………………………….8 «Mashzavod» Ltd…………………………………………………………………………………………...9 Research and Production Company (RPC) «Тensor»……………………………………………………...10 «SE Bordnetze-Ukraine» LLC (Chernivtsi region)………………………………………………….…….11 «Automotive Electric Ukraine» LLC (Chernivtsi region)…………………………………………………12 «Linhokomservis» LLC…………………………………………………………………………………...13 Institute of Thermoelectricity National Academy of Sciences and Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine…………………………………………………………………………………………………….14 Wood and forestry…………………………………………………………………….....15 Private enterprise «Kovali»………………………………………………………………………………..16 Public company «Vyzhnytsia dok»………………………………………………………………………..17 LTD «Pelet-GroupEko»…………………………………………………………………………………...18 State enterprise «Putyla forestry»………………………………………………………………………….19 State enterprise «Carpathians specialized forestry»……………………………………………………....20 Private enterprise «Lego»………………………………………………………………………………….21 «Impeks-service» LTD…………………………………………………………………………………….22 State enterprise «Sokyrianske Lisove Hospodarstvo»……………………………………………………..23 State enterprise «Storozhynets forestry»…………………………………………………………………..24 «BKM-WOOD» LLC……………………………………………………………………………………..25 State enterprise «Khotynske Lisove Hospodarstvo»………………………………………………………26 -

Historical and Cultural Heritage of the Region and Its Opportunities in Tourism and Excursion Activities (Case of Chernivtsi Region, Ukraine)

GeoJournal of Tourism and Geosites Year XI, vol. 23, no. 3, 2018, p.808-823 ISSN 2065-0817, E-ISSN 2065-1198 DOI 10.30892/gtg.23316-330 HISTORICAL AND CULTURAL HERITAGE OF THE REGION AND ITS OPPORTUNITIES IN TOURISM AND EXCURSION ACTIVITIES (CASE OF CHERNIVTSI REGION, UKRAINE) Volodymyr KROOL Yuriy Fedkovych Chernivtsi National University, Department of Physical Geography, Geomorphology and Paleogeography, 2 Kotsyubynsky Str. Chernivtsi 58012, Ukraine, e-mail: [email protected] Anatolii VDOVICHEN Chernivtsi Institute of Trade and Economics of KNUTE, Department of Management and Tourism, 7 Tsentralna Square, Chernivtsi 58002, Ukraine, e-mail: [email protected] Roman HYSHCHUK* Chernivtsi Institute of Trade and Economics of KNUTE, Department of Management and Tourism, 7 Tsentralna Square, Chernivtsi 58002, Ukraine, e-mail: [email protected] Citation: Krool, V., Vdovichen, A., & Hyshchuk, R. (2018). HISTORICAL AND CULTURAL HERITAGE OF THE REGION AND ITS OPPORTUNITIES IN TOURISM AND EXCURSION ACTIVITIES (CASE OF CHERNIVTSI REGION, UKRAINE). GeoJournal of Tourism and Geosites, 23(3), 808–823. https://doi.org/10.30892/gtg.23316-330 Abstract: Chernivtsi region in Ukraine is a unique territory where the historical and cultural heritage of different time periods is represented: from Old Russian, Ottoman, Austro-Hungarian to Romanian and Ukrainian. The purpose of the article is a comprehensive assessment of the historical and cultural heritage of the Chernivtsi region for a more intensive further involvement in the tourism industry in the Carpathian region, together with neighboring EU countries: Romania, Slovakia, Poland. For this purpose, different status, state of preservation and spatial differences were taken into account together with the resources support throughout the territory under study. -

Admin 2 Number of Partners with Ongoing

UKRAINE, Multipurpose Cash - Admin 2 Number of Partners with ongoing/completed Projects ( as of 2Sem8en iDvkaecembeSerre d2yna0-B1uda6) Novhorod-Siverskyi Yampil BELARUS Horodnia Ripky Shostka Liubeshiv Zarichne Ratne Snovsk Koriukivka Hlukhiv Kamin-Kashyrskyi Dubrovytsia Korop Shatsk Stara Chernihiv Sosnytsia Krolevets Volodymyrets Vyzhivka Kulykivka Mena Ovruch Putyvl Manevychi Sarny Rokytne Borzna Liuboml Kovel Narodychi Olevsk Konotop Buryn Bilopillia Turiisk Luhyny Krasiatychi Nizhyn Berezne Bakhmach Ivankiv Nosivka Rozhyshche Kostopil Yemilchyne Kozelets Sumy Volodymyr-Volynskyi Korosten Ichnia Talalaivka Nedryhailiv Lokachi Kivertsi Malyn Bobrovytsia Krasnopillia Romny RUSSIAN Ivanychi Lypova Lutsk Rivne Korets Novohrad-Volynskyi Borodianka Vyshhorod Pryluky Lebedyn FEDERATION Zdolbuniv Sribne Dolyna Sokal Mlyniv Radomyshl Brovary Zghurivka Demydivka Hoshcha Pulyny Cherniakhiv Makariv Trostianets Horokhiv Varva Dubno Ostroh Kyiv Baryshivka Lokhvytsia Radekhiv Baranivka Zhytomyr Brusyliv Okhtyrka Velyka Pysarivka Zolochiv Vovchansk Slavuta Boryspil Yahotyn Pyriatyn Chornukhy Hadiach Shepetivka Romaniv Korostyshiv Vasylkiv Bohodukhiv Velykyi Kamianka-buzka Radyvyliv Iziaslav Kremenets Fastiv Pereiaslav-Khmelnytskyi Hrebinka Zinkiv Krasnokutsk Burluk Bilohiria Polonne Chudniv Andrushivka Derhachi Zhovkva Busk Brody Shumsk Popilnia Obukhiv Myrhorod Kharkiv Liubar Berdychiv Bila Drabiv Kotelva Lviv Lanivtsi Kaharlyk Kolomak Valky Chuhuiv Dvorichna Troitske Zolochiv Tserkva Orzhytsia Khorol Dykanka Pechenihy Teofipol Starokostiantyniv -

Studia Humanistyczne 12 2.Indd

678',$+80$1,67<&=1($*+ 7RP http://dx.doi.org/10.7494/human.2013.12.2.65 Kateryna Shestakova* ETHNIC IDENTITY AND LINGUISTIC PRACTICES OF ROMANIANS AND MOLDOVANS (ON THE EXAMPLE OF CHERNIVTSI OBLAST, UKRAINE) In Ukraine, Chernivtsi Oblast can be observed as a region of mixed ethnic structure. As a result of historical FRQWH[WWKHUHJLRQVHHPVWRKDYHDOLQJXLVWLFVSHFL¿FLW\%DVHGRQWKHH[DPSOHRI5RPDQLDQVDQG0ROGRYDQV living in this region, we can see that ones mother tongue performs both communicative and symbolic functions (which is an important element of ethnic identity). As an element of ethnic identity the mother tongue becomes very important, especially while entering the linguistic space through language practices, and especially when HQWHULQJD6ODYLFWRQJXH 8NUDLQLDQDQG5XVVLDQ 5RPDQLDQVGRQRWKDYHSUREOHPVZLWKGH¿QLQJWKHLURZQ language and ethnicity. Some Moldovans use both names of the mother tongue (Moldovan or Romanian), DQGDFFRUGLQJO\GHFODUHWZRHWKQLFDI¿OLDWLRQV7KLVSUDFWLFHLVDUHVXOWRIWKHGHYHORSPHQWRI5RPDQLDQDQG 0ROGRYDQFXOWXUHVLQWZRGLIIHUHQWJHRSROLWLFDODUHDVZKLFKH[HUWVDVLJQL¿FDQWLQÀXHQFHRQERWKHWKQLFJURXSV Key words: social identity, ethnic identity, language practices, Romanians/ Moldovans in Ukraine, name of language PRELIMINARY FINDINGS Contemporary nation-states have profound regional dissimilarities which are often related to their multi-ethnicity. Mutual penetration of cultures is characteristic also for Ukraine, where 22.2% of the population belongs to an ethnic minority1. Similar to the background of &ULPHD=DNDUSDWWLD2EODVW+DO\FK\QD+DOL]LDDQG3RGROLDLWVGLVWLQFWVSHFL¿FDWLRQDOVR includes Chernivtsi Oblast2, which borders Romania and the Republic of Moldova. According to the Census in 2001, this oblast is 75% Ukrainian, 12% Romanian and 7.3% Moldovan, and is also home to Russians, Poles, Jews and others3. Sociological research conducted in the Chernivtsi Oblast in the early 1990s, showed that members of ethnic minorities were will- ing to change their status. -

Investment Proposal (Project) Application Form of GREENFIЕLD Land

Investment proposal (project) application form of GREENFIЕLD land lot General information Title of the investment proposal (project) Construction of the recreational complex «Stanchyna» Location (district, city/village, street), land photo, Bahna vil., Vyzhnytsia district, Chernivtsi region scheme of location Owner (owners) Community of Bahna vil. Available documents, that certify the ownership General plan of construction (official act, certificate of ownership) Preliminary cost (balanced cost, assessed value) 100,0 ths. UAH The actual usage Pasture Technical parameters of a land lot Area of the available land lot, ha 45,4 Border surroundings (description, scheme) Borders on the state forestry Level difference on the land lot, m 50 m Cadastral end use Pasture Proposed end use For construction of touristic and recreational center, skiing track Ground-based obstacles (risk of flood and No obstacles landslide, ecological conditions) Underground obstacles (level of surface and No obstacles subterranean waters) Limitations in use (due to construction, ecology According to the requirements of land ownership etc.) and good-neighborly relations Utilities Water (availability, parameters) Distance to the source of fresh water – 250 m Drainage system (availability, parameters) Not available Supplying with gas (availability, parameters) Distance to the gas supplying net – 3,1 km. Electricity (availability, parameters) Distance to the available electrical substation -1 km Availability Ways of communication to the object (autoroads, Automobile gravel -

Jewish Cemeteries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine

JEWISH CEMETERIES, SYNAGOGUES, AND MASS GRAVE SITES IN UKRAINE United States Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad 2005 UNITED STATES COMMISSION FOR THE PRESERVATION OF AMERICA’S HERITAGE ABROAD Warren L. Miller, Chairman McLean, VA Members: Ned Bandler August B. Pust Bridgewater, CT Euclid, OH Chaskel Besser Menno Ratzker New York, NY Monsey, NY Amy S. Epstein Harriet Rotter Pinellas Park, FL Bingham Farms, MI Edgar Gluck Lee Seeman Brooklyn, NY Great Neck, NY Phyllis Kaminsky Steven E. Some Potomac, MD Princeton, NJ Zvi Kestenbaum Irving Stolberg Brooklyn, NY New Haven, CT Daniel Lapin Ari Storch Mercer Island, WA Potomac, MD Gary J. Lavine Staff: Fayetteville, NY Jeffrey L. Farrow Michael B. Levy Executive Director Washington, DC Samuel Gruber Rachmiel Liberman Research Director Brookline, MA Katrina A. Krzysztofiak Laura Raybin Miller Program Manager Pembroke Pines, FL Patricia Hoglund Vincent Obsitnik Administrative Officer McLean, VA 888 17th Street, N.W., Suite 1160 Washington, DC 20006 Ph: ( 202) 254-3824 Fax: ( 202) 254-3934 E-mail: [email protected] May 30, 2005 Message from the Chairman One of the principal missions that United States law assigns the Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad is to identify and report on cemeteries, monuments, and historic buildings in Central and Eastern Europe associated with the cultural heritage of U.S. citizens, especially endangered sites. The Congress and the President were prompted to establish the Commission because of the special problem faced by Jewish sites in the region: The communities that had once cared for the properties were annihilated during the Holocaust.