Neighbors' Contribution to the Mass Killing of Jews in Northern

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TEKA Komisji Architektury, Urbanistyki I Studiów Krajobrazowych XV-2 2019

TEKA 2019, Nr 2 Komisji Architektury, Urbanistyki i Studiów Krajobrazowych Oddział Polskiej Akademii Nauk w Lublinie Revisited the localization of fortifications of the 18th century on the surroundings of village of Braha in Khmelnytsky region Oleksandr harlan https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1473-6417 [email protected] Department of Design and Reconstruction of the Architectural Environment, Prydniprovs’ka State Academy of Civil Engineering and Architecture Abstract: the results of the survey of the territories of the village Braga in the Khmelnytsky region, which is in close prox- imity to Khotyn Fortress, are highlighted in this article. A general description of the sources that has thrown a great deal of light on the fortifications of the left bank of the Dnister River opposite the Khotyn Fortress according to the modern land- scape, is presented. Keywords: monument, fortification, village of Braga, Khotyn fortress, Dnister River Relevance of research Today there is a lack of architectural and urban studies in the context of studying the history of the unique monument – the Khotyn Fortress. Only a few published works can be cited that cover issues of origin, existence of fortifications and it’s preservation. To take into comprehensive account of the specific conservation needs of the Khotyn Fortress, it was necessary to carry out appropriate research works (bibliographic, archival, cartographic, iconographic), including on-site surveys. During 2014−2015, the research works had been carried out by the Research Institute of Conservation Research in the context of the implementation of the Plan for the organization of the territory of the State. During the elaboration of historical sources from the history of the city of Khotyn and the Khotyn Fortress it was put a spotlight on a great number of iconographic materials, concerning the recording of the fortifica- tions of the New Fortress of the 18th-19th centuries. -

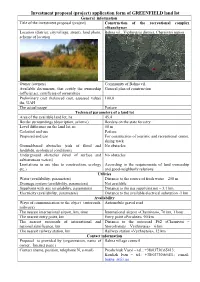

Investment Proposal (Project) Application Form of GREENFIЕLD

Investment proposal (project) application form of GREENFIЕLD land lot General information Title of the investment proposal (project) Construction of the recreational complex «Stanchyna» Location (district, city/village, street), land photo, Bahna vil., Vyzhnytsia district, Chernivtsi region scheme of location Owner (owners) Community of Bahna vil. Available documents, that certify the ownership General plan of construction (official act, certificate of ownership) Preliminary cost (balanced cost, assessed value) 100,0 ths. UAH The actual usage Pasture Technical parameters of a land lot Area of the available land lot, ha 45,4 Border surroundings (description, scheme) Borders on the state forestry Level difference on the land lot, m 50 m Cadastral end use Pasture Proposed end use For construction of touristic and recreational center, skiing track Ground-based obstacles (risk of flood and No obstacles landslide, ecological conditions) Underground obstacles (level of surface and No obstacles subterranean waters) Limitations in use (due to construction, ecology According to the requirements of land ownership etc.) and good-neighborly relations Utilities Water (availability, parameters) Distance to the source of fresh water – 250 m Drainage system (availability, parameters) Not available Supplying with gas (availability, parameters) Distance to the gas supplying net – 3,1 km. Electricity (availability, parameters) Distance to the available electrical substation -1 km Availability Ways of communication to the object (autoroads, Automobile gravel -

Dry Grassland Vegetation of Central Podolia (Ukraine) - a Preliminary Overview of Its Syntaxonomy, Ecology and Biodiversity 391-430 Tuexenia 34: 391–430

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Tuexenia - Mitteilungen der Floristisch-soziologischen Arbeitsgemeinschaft Jahr/Year: 2014 Band/Volume: NS_34 Autor(en)/Author(s): Kuzenko Anna A., Becker Thomas, Didukh Yakiv P., Ardelean Ioana Violeta, Becker Ute, Beldean Monika, Dolnik Christian, Jeschke Michael, Naqinezhad Alireza, Ugurlu Emin, Unal Aslan, Vassilev Kiril, Vorona Evgeniy I., Yavorska Olena H., Dengler Jürgen Artikel/Article: Dry grassland vegetation of Central Podolia (Ukraine) - a preliminary overview of its syntaxonomy, ecology and biodiversity 391-430 Tuexenia 34: 391–430. Göttingen 2014. doi: 10.14471/2014.34.020, available online at www.tuexenia.de Dry grassland vegetation of Central Podolia (Ukraine) – a preliminary overview of its syntaxonomy, ecology and biodiversity Die Trockenrasenvegetation Zentral-Podoliens (Ukraine) – eine vorläufige Übersicht zu Syntaxonomie, Ökologie und Biodiversität Anna A. Kuzemko1, Thomas Becker2, Yakiv P. Didukh3, Ioana Violeta Arde- lean4, Ute Becker5, Monica Beldean4, Christian Dolnik6, Michael Jeschke2, Alireza Naqinezhad7, Emin Uğurlu8, Aslan Ünal9, Kiril Vassilev10, Evgeniy I. Vorona11, Olena H. Yavorska11 & Jürgen Dengler12,13,14,* 1National Dendrological Park “Sofiyvka”, National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, Kyivska Str. 12a, 20300 Uman’, Ukraine, [email protected];2Geobotany, Faculty of Geography and Geosciences, University of Trier, Behringstr. 21, 54296 Trier, Germany, [email protected]; -

Territorial Structure of the West-Ukrainian Region Settling System

Słupskie Prace Geograficzne 8 • 2011 Vasyl Dzhaman Yuriy Fedkovych National University Chernivtsi (Ukraine) TERRITORIAL STRUCTURE OF THE WEST-UKRAINIAN REGION SETTLING SYSTEM STRUKTURA TERYTORIALNA SYSTEMU ZASIEDLENIA NA TERYTORIUM ZACHODNIEJ UKRAINY Zarys treści : W artykule podjęto próbę charakterystyki elementów struktury terytorialnej sys- temu zasiedlenia Ukrainy Zachodniej. Określono zakres organizacji przestrzennej tego systemu, uwzględniając elementy społeczno-geograficzne zachodniego makroregionu Ukrainy. Na podstawie przeprowadzonych badań należy stwierdzić, że struktura terytorialna organizacji produkcji i rozmieszczenia ludności zachodniej Ukrainy na charakter radialno-koncentryczny, co jest optymalnym wariantem kompozycji przestrzennej układu społecznego regionu. Słowa kluczowe : system zaludnienia, Ukraina Zachodnia Key words : settling system, West Ukraine Problem Statement Improvement of territorial structure of settling systems is among the major prob- lems when it regards territorial organization of social-geographic complexes. Ac- tuality of the problem is evidenced by introducing of the Territory Planning and Building Act, Ukraine, of 20 April 2000, and the General Scheme of Ukrainian Ter- ritory Planning Act, Ukraine, of 7 February 2002, both Acts establishing legal and organizational bases for planning, cultivation and provision of stable progress in in- habited localities, development of industrial, social and engineering-transport infra- structure ( Territory Planning and Building ... 2002, General Scheme of Ukrainian Territory ... 2002). Initial Premises Need for improvement of territorial organization of productive forces on specific stages of development delineates a circle of problems that require scientific research. 27 When studying problems of settling in 50-70-ies of the 20 th century, national geo- graphical science focused the majority of its attention upon separate towns and cit- ies, in particular, upon limitation of population increase in big cities, and to active growth of mid and small-sized towns. -

The Role of Bohdan Khmelnytskyi and the Kozaks in the Rusin Struggle for Independence from the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth: 1648--1649

University of Windsor Scholarship at UWindsor Electronic Theses and Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, and Major Papers 1-1-1967 The role of Bohdan Khmelnytskyi and the Kozaks in the Rusin struggle for independence from the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth: 1648--1649. Andrew B. Pernal University of Windsor Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd Recommended Citation Pernal, Andrew B., "The role of Bohdan Khmelnytskyi and the Kozaks in the Rusin struggle for independence from the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth: 1648--1649." (1967). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 6490. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd/6490 This online database contains the full-text of PhD dissertations and Masters’ theses of University of Windsor students from 1954 forward. These documents are made available for personal study and research purposes only, in accordance with the Canadian Copyright Act and the Creative Commons license—CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution, Non-Commercial, No Derivative Works). Under this license, works must always be attributed to the copyright holder (original author), cannot be used for any commercial purposes, and may not be altered. Any other use would require the permission of the copyright holder. Students may inquire about withdrawing their dissertation and/or thesis from this database. For additional inquiries, please contact the repository administrator via email ([email protected]) or by telephone at 519-253-3000ext. 3208. THE ROLE OF BOHDAN KHMELNYTSKYI AND OF THE KOZAKS IN THE RUSIN STRUGGLE FOR INDEPENDENCE FROM THE POLISH-LI'THUANIAN COMMONWEALTH: 1648-1649 by A ‘n d r e w B. Pernal, B. A. A Thesis Submitted to the Department of History of the University of Windsor in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Faculty of Graduate Studies 1967 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

Did Authorities Crush Russian Orthodox Church Abroad Parish?

FORUM 18 NEWS SERVICE, Oslo, Norway http://www.forum18.org/ The right to believe, to worship and witness The right to change one's belief or religion The right to join together and express one's belief This article was published by F18News on: 4 October 2005 UKRAINE: Did authorities crush Russian Orthodox Church Abroad parish? By Felix Corley, Forum 18 News Service <http://www.forum18.org> Archbishop Agafangel (Pashkovsky) of the Odessa Diocese of the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad (ROCA) has told Forum 18 News Service that the authorities in western Ukraine have crushed a budding parish of his church, at the instigation of Metropolitan Onufry, the diocesan bishop of the rival Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate. The head of the village administration, Vasyl Gavrish, denies claims that he threatened parishioners after the ROCA parish submitted a state registration application. When asked by Forum 18 whether an Orthodox church from a non-Moscow Patriarchate jurisdiction could gain registration, Gavrish replied: "We already have a parish of the Moscow Patriarchate here." Both Gavrish and parishioners have stated that the state SBU security service was involved in moves against the parish, but the SBU has denied this along with Bishop Agafangel's claim that there was pressure from the Moscow Patriarchate. Archbishop Agafangel (Pashkovsky) of the Odessa Diocese of the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad (ROCA) has accused the authorities of crushing a budding parish of his church, in the small village of Grozintsy in Khotin [Khotyn] district of Chernivtsy [Chernivtsi] region, in western Ukraine bordering Romania. "People were afraid of the authorities' threats and withdrew their signatures on the parish's registration application," he told Forum 18 News Service from Odessa on 27 September. -

Resources Concerning the History of Polish Jews in Castle Court Records of the 17Th and 18Th Centuries in the Central State Historical Archives in Kyiv and Lviv

SCRIPTA JUDAICA CRACOVIENSIA Vol. 18 (2020) pp. 127–140 doi:10.4467/20843925SJ.20.009.13877 www.ejournals.eu/Scripta-Judaica-Cracoviensia Resources Concerning the History of Polish Jews in Castle Court Records of the 17th and 18th Centuries in the Central State Historical Archives in Kyiv and Lviv Przemysław Zarubin https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4845-0839 (Jagiellonian University in Krakow, Poland) e-mail: [email protected] Keywords: archival sources, Ukraine, Lviv, Kyiv, castle court, 17th century, 18th century Abstract: The article presents types of sources which have thus far not been used, castle court books kept in the archives of the Ukrainian cities of Lviv and Kyiv. The author emphasizes the importance of these sources for research on the history and culture of Polish Jews in the 17th and 18th centuries. He also specifies the types of documents related to Jewish issues authenticated in these books (e.g. manifestations and lawsuits, declarations of the Radom Tribunal), as well as current source publications and internet databases containing selected documents from Ukrainian archives. The Central State Historical Archive in Lviv (CDIAL) (known as the Bernadine Ar- chive) and the Central State Historical Archive in Kyiv (CDIAUK) both have exten- sive collections of records of the so-called castle courts (sądy grodzkie), also known as local Starost courts (sądy starościńskie) for the nobility: from the Bełz and Ruthe- nian Voivodeships in the Lviv archive; and from the Łuck, Podolia, Kyiv, and Bracław Voivodeships in the Kyiv archive. This is particularly important because – in the light of Jewish population counts taken in 1764–1765 for the purpose of poll tax assessment – these areas were highly populated by Jews. -

1768-1830S a Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate

A PLAGUE ON BOTH HOUSES?: POPULATION MOVEMENTS AND THE SPREAD OF DISEASE ACROSS THE OTTOMAN-RUSSIAN BLACK SEA FRONTIER, 1768-1830S A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History By Andrew Robarts, M.S.F.S. Washington, DC December 17, 2010 Copyright 2010 by Andrew Robarts All Rights Reserved ii A PLAGUE ON BOTH HOUSES?: POPULATION MOVEMENTS AND THE SPREAD OF DISEASE ACROSS THE OTTOMAN-RUSSIAN BLACK SEA FRONTIER, 1768-1830S Andrew Robarts, M.S.F.S. Dissertation Advisor: Catherine Evtuhov, Ph. D. ABSTRACT Based upon a reading of Ottoman, Russian, and Bulgarian archival documents, this dissertation examines the response by the Ottoman and Russian states to the accelerated pace of migration and spread of disease in the Black Sea region from the outbreak of the Russo-Ottoman War of 1768-1774 to the signing of the Treaty of Hünkar Iskelesi in 1833. Building upon introductory chapters on the Russian-Ottoman Black Sea frontier and a case study of Bulgarian population movements between the Russian and Ottoman Empires, this dissertation analyzes Russian and Ottoman migration and settlement policies, the spread of epidemic diseases (plague and cholera) in the Black Sea region, the construction of quarantines and the implementation of travel document regimes. The role and position of the Danubian Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia as the “middle ground” between the Ottoman and Russian Empires -

SITUATION with STUDYING the HISTORY of the UKRAINIAN COSSACK STATE USING the TURK-OTTOMAN SOURCES Ferhad TURANLY

Karadeniz İncelemeleri Dergisi: Yıl 8, Sayı 15, Güz 2013 205 SITUATION WITH STUDYING THE HISTORY OF THE UKRAINIAN COSSACK STATE USING THE TURK-OTTOMAN SOURCES Ferhad TURANLY ABSTRACT Available studies of the Turk-Ottoman sources on the history of Ukraine in the period of Cossacks have been presented and considered. The problem concerning development of the Oriental Studies has been analysed. There has been used a methodology that is a new contribution to the academic study of the issues relating to the history of the development of relations between the Cossack Hetman Ukraine and the Ottoman State. Keywords: Ottoman, Ukrainan, a Cossack, a study, oriental studies. OSMANLI-TÜRK KAYNAKLARINA GÖRE UKRAYNA KOZAK DÖNEMİ TARİH ÇALIŞMALARI ÖZ Bu makalede, Ukrayna Kozak dönemi tarihi hakkında Osmanlı zamanında ortaya çıkmış araştırmalar değerlendirilmiştir. Söz konusu kaynakların Ukrayna tarihi açısından ele alındığı araştırmada Şarkiyat biliminin gelişmesiyle iligili sorunlardan da bahsolunmaktadır. Uygun usullerin kullanılmasıyla, bu kaynakla- rın, Kazak Hetman Ukraynası ve Osmanlı Devleti arasındaki ilişki- lerin tarihinin derinliğinin öğrenilmesini sağlayacağı, araştırmada varılan temel sonuçlardan biridir. Anahtar Sözcükler: Araştırma, Şarkiyat, Kozak, Osmanlı, Ukrayna. A reader at Kyiv National University “Kyiv Mohyla Academy”, [email protected] 206 Journal of Black Sea Studies: Year 8, Number 15, Autumn 2013 In the source base on Ukraine’s History and Culture, in particular, concerning its Cossack-Hetman period, an important place belongs to a complex of Arabic graphic texts, as an important part of which we consider a series of Turk sources – written and other kinds of historical commemorative books and documents, whose authors originated from the countries populated by the Turk ethnic groups. -

The History of Ukraine Advisory Board

THE HISTORY OF UKRAINE ADVISORY BOARD John T. Alexander Professor of History and Russian and European Studies, University of Kansas Robert A. Divine George W. Littlefield Professor in American History Emeritus, University of Texas at Austin John V. Lombardi Professor of History, University of Florida THE HISTORY OF UKRAINE Paul Kubicek The Greenwood Histories of the Modern Nations Frank W. Thackeray and John E. Findling, Series Editors Greenwood Press Westport, Connecticut • London Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Kubicek, Paul. The history of Ukraine / Paul Kubicek. p. cm. — (The Greenwood histories of the modern nations, ISSN 1096 –2095) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978 – 0 –313 – 34920 –1 (alk. paper) 1. Ukraine —History. I. Title. DK508.51.K825 2008 947.7— dc22 2008026717 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available. Copyright © 2008 by Paul Kubicek All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2008026717 ISBN: 978– 0– 313 – 34920 –1 ISSN: 1096 –2905 First published in 2008 Greenwood Press, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. www.greenwood.com Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this book complies with the Permanent Paper Standard issued by the National Information Standards Organization (Z39.48 –1984). 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Every reasonable effort has been made to trace the owners of copyright materials in this book, but in some instances this has proven impossible. -

Time and Place

One Time and Place We do not live in a void. We never suffer from a fear of roaming about in the emptiness of Time. We own the past and are, hence, not afraid of what is to be. —Abraham Heschel, The Earth is the Lord’s * Novokonstantinov When you asked my father where he came from, he told you precise- ly. He was born and raised in a shtetl, Novokonstantinov, in the guber- nia (province) of Podolia, in Ukraine, Russia. My father pronounced it Neye-constanteen, and referred to it as Constantine. The townspeople called themselves Constantines. The town was on the river, the South- ern Buh (pronounced “bug”), and, until the Nazis built the European highway and bridge that bypassed the town, the ford in the river at Novokonstantinov was a vital east-west passageway for ordinary travel, commerce, and the military over the years. Across the centuries through to the Second World War, thousands of cavalry passed through the rocky ford in the river at Novokonstan- * Heschel, A. (1995). The earth is the Lord’s: The inner world of the Jew in Eastern Europe. New York, NY: Jewish Lights Edition, published by arrangement with Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 1 2 A Man Comes from Someplace tinov. The town was likely named by the Turks during their occupa- tion of the territory in the late 17th century, but there are prehistoric remains all around. No doubt, Styroconstantinov (Old Constantine) was renamed then, too, and the new town, my father said, was seen at the time of the Turkish occupation as having the potential to become a new Constantinople. -

Vasyl BOTUSHANSKYY(Chernivtsi) the SOURCES of STATE

Vasyl BOTUSHANSKYY(Chernivtsi) THE SOURCES OF STATE ARCHIVES OF CHERNIVTSI REGION AS COMPONENT OF STUDIING THE EVENTS OF THE WORLD WAR I AT BUKOVYNA This article gives an overview of the sources of the State Archives of Chernivtsi region, including funds of the Austrian and Russian occupation administrations acting in Bukovina in 1914 - 1918, which recorded information about the events of World War I in the region and that can serve as sources for research of the history of these events. Keywords: Bucovina, archive, fund, information, military, troops, war, occupation, empire, requisition, refugees, internment, deportation. 1914 year - the year of the First World War, but not last, and a hundred years it was the most ambitious and bloody war, which is known to humanity, killed 10 million. People., Injuring about 20 million. The war engulfed vast areas of the world, first of all the leading countries of military-political blocs: the Triple (Germany and Austria-Hungary) and the Entente (Russia, Great Britain and France). Have covered the war and area of residence of the Ukrainian people - eastern Ukraine, which was part of the Russian Empire and the West in the empire of Austria-Hungary, including Galicia and Bukovina. Ukrainian tragedy of this war was that mobilized in the opposite army, they were forced to kill each other. Coverage of the history of World War II Ukrainian lands, including and Bukovina, has dedicated many works, and this research continues. Of course, they would have been impossible without the historical sources. For the sake of objectivity it should be recognized that archaeography Bukovina already has on this issue considerable achievements, but many more sources should be identified and investigated.