Commemorating the Future in Post-War Chernivtsi 437

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TEKA Komisji Architektury, Urbanistyki I Studiów Krajobrazowych XV-2 2019

TEKA 2019, Nr 2 Komisji Architektury, Urbanistyki i Studiów Krajobrazowych Oddział Polskiej Akademii Nauk w Lublinie Revisited the localization of fortifications of the 18th century on the surroundings of village of Braha in Khmelnytsky region Oleksandr harlan https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1473-6417 [email protected] Department of Design and Reconstruction of the Architectural Environment, Prydniprovs’ka State Academy of Civil Engineering and Architecture Abstract: the results of the survey of the territories of the village Braga in the Khmelnytsky region, which is in close prox- imity to Khotyn Fortress, are highlighted in this article. A general description of the sources that has thrown a great deal of light on the fortifications of the left bank of the Dnister River opposite the Khotyn Fortress according to the modern land- scape, is presented. Keywords: monument, fortification, village of Braga, Khotyn fortress, Dnister River Relevance of research Today there is a lack of architectural and urban studies in the context of studying the history of the unique monument – the Khotyn Fortress. Only a few published works can be cited that cover issues of origin, existence of fortifications and it’s preservation. To take into comprehensive account of the specific conservation needs of the Khotyn Fortress, it was necessary to carry out appropriate research works (bibliographic, archival, cartographic, iconographic), including on-site surveys. During 2014−2015, the research works had been carried out by the Research Institute of Conservation Research in the context of the implementation of the Plan for the organization of the territory of the State. During the elaboration of historical sources from the history of the city of Khotyn and the Khotyn Fortress it was put a spotlight on a great number of iconographic materials, concerning the recording of the fortifica- tions of the New Fortress of the 18th-19th centuries. -

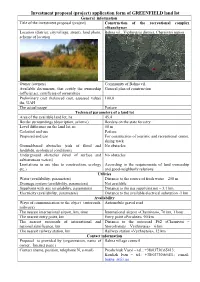

Investment Proposal (Project) Application Form of GREENFIЕLD

Investment proposal (project) application form of GREENFIЕLD land lot General information Title of the investment proposal (project) Construction of the recreational complex «Stanchyna» Location (district, city/village, street), land photo, Bahna vil., Vyzhnytsia district, Chernivtsi region scheme of location Owner (owners) Community of Bahna vil. Available documents, that certify the ownership General plan of construction (official act, certificate of ownership) Preliminary cost (balanced cost, assessed value) 100,0 ths. UAH The actual usage Pasture Technical parameters of a land lot Area of the available land lot, ha 45,4 Border surroundings (description, scheme) Borders on the state forestry Level difference on the land lot, m 50 m Cadastral end use Pasture Proposed end use For construction of touristic and recreational center, skiing track Ground-based obstacles (risk of flood and No obstacles landslide, ecological conditions) Underground obstacles (level of surface and No obstacles subterranean waters) Limitations in use (due to construction, ecology According to the requirements of land ownership etc.) and good-neighborly relations Utilities Water (availability, parameters) Distance to the source of fresh water – 250 m Drainage system (availability, parameters) Not available Supplying with gas (availability, parameters) Distance to the gas supplying net – 3,1 km. Electricity (availability, parameters) Distance to the available electrical substation -1 km Availability Ways of communication to the object (autoroads, Automobile gravel -

Territorial Structure of the West-Ukrainian Region Settling System

Słupskie Prace Geograficzne 8 • 2011 Vasyl Dzhaman Yuriy Fedkovych National University Chernivtsi (Ukraine) TERRITORIAL STRUCTURE OF THE WEST-UKRAINIAN REGION SETTLING SYSTEM STRUKTURA TERYTORIALNA SYSTEMU ZASIEDLENIA NA TERYTORIUM ZACHODNIEJ UKRAINY Zarys treści : W artykule podjęto próbę charakterystyki elementów struktury terytorialnej sys- temu zasiedlenia Ukrainy Zachodniej. Określono zakres organizacji przestrzennej tego systemu, uwzględniając elementy społeczno-geograficzne zachodniego makroregionu Ukrainy. Na podstawie przeprowadzonych badań należy stwierdzić, że struktura terytorialna organizacji produkcji i rozmieszczenia ludności zachodniej Ukrainy na charakter radialno-koncentryczny, co jest optymalnym wariantem kompozycji przestrzennej układu społecznego regionu. Słowa kluczowe : system zaludnienia, Ukraina Zachodnia Key words : settling system, West Ukraine Problem Statement Improvement of territorial structure of settling systems is among the major prob- lems when it regards territorial organization of social-geographic complexes. Ac- tuality of the problem is evidenced by introducing of the Territory Planning and Building Act, Ukraine, of 20 April 2000, and the General Scheme of Ukrainian Ter- ritory Planning Act, Ukraine, of 7 February 2002, both Acts establishing legal and organizational bases for planning, cultivation and provision of stable progress in in- habited localities, development of industrial, social and engineering-transport infra- structure ( Territory Planning and Building ... 2002, General Scheme of Ukrainian Territory ... 2002). Initial Premises Need for improvement of territorial organization of productive forces on specific stages of development delineates a circle of problems that require scientific research. 27 When studying problems of settling in 50-70-ies of the 20 th century, national geo- graphical science focused the majority of its attention upon separate towns and cit- ies, in particular, upon limitation of population increase in big cities, and to active growth of mid and small-sized towns. -

Did Authorities Crush Russian Orthodox Church Abroad Parish?

FORUM 18 NEWS SERVICE, Oslo, Norway http://www.forum18.org/ The right to believe, to worship and witness The right to change one's belief or religion The right to join together and express one's belief This article was published by F18News on: 4 October 2005 UKRAINE: Did authorities crush Russian Orthodox Church Abroad parish? By Felix Corley, Forum 18 News Service <http://www.forum18.org> Archbishop Agafangel (Pashkovsky) of the Odessa Diocese of the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad (ROCA) has told Forum 18 News Service that the authorities in western Ukraine have crushed a budding parish of his church, at the instigation of Metropolitan Onufry, the diocesan bishop of the rival Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate. The head of the village administration, Vasyl Gavrish, denies claims that he threatened parishioners after the ROCA parish submitted a state registration application. When asked by Forum 18 whether an Orthodox church from a non-Moscow Patriarchate jurisdiction could gain registration, Gavrish replied: "We already have a parish of the Moscow Patriarchate here." Both Gavrish and parishioners have stated that the state SBU security service was involved in moves against the parish, but the SBU has denied this along with Bishop Agafangel's claim that there was pressure from the Moscow Patriarchate. Archbishop Agafangel (Pashkovsky) of the Odessa Diocese of the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad (ROCA) has accused the authorities of crushing a budding parish of his church, in the small village of Grozintsy in Khotin [Khotyn] district of Chernivtsy [Chernivtsi] region, in western Ukraine bordering Romania. "People were afraid of the authorities' threats and withdrew their signatures on the parish's registration application," he told Forum 18 News Service from Odessa on 27 September. -

SITUATION with STUDYING the HISTORY of the UKRAINIAN COSSACK STATE USING the TURK-OTTOMAN SOURCES Ferhad TURANLY

Karadeniz İncelemeleri Dergisi: Yıl 8, Sayı 15, Güz 2013 205 SITUATION WITH STUDYING THE HISTORY OF THE UKRAINIAN COSSACK STATE USING THE TURK-OTTOMAN SOURCES Ferhad TURANLY ABSTRACT Available studies of the Turk-Ottoman sources on the history of Ukraine in the period of Cossacks have been presented and considered. The problem concerning development of the Oriental Studies has been analysed. There has been used a methodology that is a new contribution to the academic study of the issues relating to the history of the development of relations between the Cossack Hetman Ukraine and the Ottoman State. Keywords: Ottoman, Ukrainan, a Cossack, a study, oriental studies. OSMANLI-TÜRK KAYNAKLARINA GÖRE UKRAYNA KOZAK DÖNEMİ TARİH ÇALIŞMALARI ÖZ Bu makalede, Ukrayna Kozak dönemi tarihi hakkında Osmanlı zamanında ortaya çıkmış araştırmalar değerlendirilmiştir. Söz konusu kaynakların Ukrayna tarihi açısından ele alındığı araştırmada Şarkiyat biliminin gelişmesiyle iligili sorunlardan da bahsolunmaktadır. Uygun usullerin kullanılmasıyla, bu kaynakla- rın, Kazak Hetman Ukraynası ve Osmanlı Devleti arasındaki ilişki- lerin tarihinin derinliğinin öğrenilmesini sağlayacağı, araştırmada varılan temel sonuçlardan biridir. Anahtar Sözcükler: Araştırma, Şarkiyat, Kozak, Osmanlı, Ukrayna. A reader at Kyiv National University “Kyiv Mohyla Academy”, [email protected] 206 Journal of Black Sea Studies: Year 8, Number 15, Autumn 2013 In the source base on Ukraine’s History and Culture, in particular, concerning its Cossack-Hetman period, an important place belongs to a complex of Arabic graphic texts, as an important part of which we consider a series of Turk sources – written and other kinds of historical commemorative books and documents, whose authors originated from the countries populated by the Turk ethnic groups. -

The History of Ukraine Advisory Board

THE HISTORY OF UKRAINE ADVISORY BOARD John T. Alexander Professor of History and Russian and European Studies, University of Kansas Robert A. Divine George W. Littlefield Professor in American History Emeritus, University of Texas at Austin John V. Lombardi Professor of History, University of Florida THE HISTORY OF UKRAINE Paul Kubicek The Greenwood Histories of the Modern Nations Frank W. Thackeray and John E. Findling, Series Editors Greenwood Press Westport, Connecticut • London Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Kubicek, Paul. The history of Ukraine / Paul Kubicek. p. cm. — (The Greenwood histories of the modern nations, ISSN 1096 –2095) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978 – 0 –313 – 34920 –1 (alk. paper) 1. Ukraine —History. I. Title. DK508.51.K825 2008 947.7— dc22 2008026717 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available. Copyright © 2008 by Paul Kubicek All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2008026717 ISBN: 978– 0– 313 – 34920 –1 ISSN: 1096 –2905 First published in 2008 Greenwood Press, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. www.greenwood.com Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this book complies with the Permanent Paper Standard issued by the National Information Standards Organization (Z39.48 –1984). 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Every reasonable effort has been made to trace the owners of copyright materials in this book, but in some instances this has proven impossible. -

Jewish Cemetries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine

Syracuse University SURFACE Religion College of Arts and Sciences 2005 Jewish Cemetries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine Samuel D. Gruber United States Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/rel Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Gruber, Samuel D., "Jewish Cemeteries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine" (2005). Full list of publications from School of Architecture. Paper 94. http://surface.syr.edu/arc/94 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts and Sciences at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Religion by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JEWISH CEMETERIES, SYNAGOGUES, AND MASS GRAVE SITES IN UKRAINE United States Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad 2005 UNITED STATES COMMISSION FOR THE PRESERVATION OF AMERICA’S HERITAGE ABROAD Warren L. Miller, Chairman McLean, VA Members: Ned Bandler August B. Pust Bridgewater, CT Euclid, OH Chaskel Besser Menno Ratzker New York, NY Monsey, NY Amy S. Epstein Harriet Rotter Pinellas Park, FL Bingham Farms, MI Edgar Gluck Lee Seeman Brooklyn, NY Great Neck, NY Phyllis Kaminsky Steven E. Some Potomac, MD Princeton, NJ Zvi Kestenbaum Irving Stolberg Brooklyn, NY New Haven, CT Daniel Lapin Ari Storch Mercer Island, WA Potomac, MD Gary J. Lavine Staff: Fayetteville, NY Jeffrey L. Farrow Michael B. Levy Executive Director Washington, DC Samuel Gruber Rachmiel -

The Residence of Bukovyna and Dalmatia Metropolitans in Chernivtsi

THE RESIDENCE OF BUKOVYNA AND DALMATIA METROPOLITANS IN CHERNIVTSI NOMINATION BY THE GOVERNMENT OF UKRAINE OF THE FOR INSCRIPTION THE RESIDENCE OF BUKOVYNA AND DALMATIA METROPOLITANS I N CHERNIVTSI ON THE WORLD HERITAGE LIST 2008 PREPARED BY GOVERNMENT OF UKRAINE, STATE AND LOCAL AUTHORITIES AND THE ACADEMIC COUNCIL OF YURIJ FEDKOVYCH NATIONAL UNIVERSITY TABLE OF CONTENTS Summery…………………………………………………………………………..…5 1. IDENTIFICATION OF THE PROPERTY 1.A Country . …... 16 1.B State, province or region . …………..…18 1.C Name of property . …….….19 1.D Geographical coordinates to the nearest second. Property description . ……. 19 1.E Maps and plans . ………...20 1.F Area of nominated property and proposed buffer zone . .. … . ..22 2. DESCRIPTION 2.A Description of property . ………........26 2.B History and development . .………………..38 3. JUSTIFICATION FOR INSCRIPTION 3.A Criteria under which inscription is proposed and justifi cation for inscription 48 3.B Proposed statement of outstanding universal value . 54 3.C Comparative analysis . 55 3.D Integrity and authenticity . 75 4. STATE OF CONSERVATION AND FACTORS AFFECTING THE PROPERTY 4.A Present state of conservation . .79 4.B Factors affecting the property . 79 (i) Development pressures . 80 (ii) Environmental pressures . 80 (iii) Natural disasters and risk preparedness . 80 (iv) Visitor/tourism pressures . 81 (v) Number of inhabitants within the property and the buffer zone . .. 87 5. PROTECTION AND MANAGEMENT OF THE PROPERTY 5.A Ownership . 90 5.B Protective designation . 98 5.C Means of implementing protective measures . 110 5.D Existing plans related to municipality and region in which the proposed property is located . 111 5.E Property management plan or other management system . -

1 Introduction

State Service of Geodesy, Cartography and Cadastre State Scientific Production Enterprise “Kartographia” TOPONYMIC GUIDELINES For map and other editors For international use Ukraine Kyiv “Kartographia” 2011 TOPONYMIC GUIDELINES FOR MAP AND OTHER EDITORS, FOR INTERNATIONAL USE UKRAINE State Service of Geodesy, Cartography and Cadastre State Scientific Production Enterprise “Kartographia” ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Prepared by Nina Syvak, Valerii Ponomarenko, Olha Khodzinska, Iryna Lakeichuk Scientific Consultant Iryna Rudenko Reviewed by Nataliia Kizilowa Translated by Olha Khodzinska Editor Lesia Veklych ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ © Kartographia, 2011 ISBN 978-966-475-839-7 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction ................................................................ 5 2 The Ukrainian Language............................................ 5 2.1 General Remarks.............................................. 5 2.2 The Ukrainian Alphabet and Romanization of the Ukrainian Alphabet ............................... 6 2.3 Pronunciation of Ukrainian Geographical Names............................................................... 9 2.4 Stress .............................................................. 11 3 Spelling Rules for the Ukrainian Geographical Names....................................................................... 11 4 Spelling of Generic Terms ....................................... 13 5 Place Names in Minority Languages -

Jewish Cemeteries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine

JEWISH CEMETERIES, SYNAGOGUES, AND MASS GRAVE SITES IN UKRAINE United States Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad 2005 UNITED STATES COMMISSION FOR THE PRESERVATION OF AMERICA’S HERITAGE ABROAD Warren L. Miller, Chairman McLean, VA Members: Ned Bandler August B. Pust Bridgewater, CT Euclid, OH Chaskel Besser Menno Ratzker New York, NY Monsey, NY Amy S. Epstein Harriet Rotter Pinellas Park, FL Bingham Farms, MI Edgar Gluck Lee Seeman Brooklyn, NY Great Neck, NY Phyllis Kaminsky Steven E. Some Potomac, MD Princeton, NJ Zvi Kestenbaum Irving Stolberg Brooklyn, NY New Haven, CT Daniel Lapin Ari Storch Mercer Island, WA Potomac, MD Gary J. Lavine Staff: Fayetteville, NY Jeffrey L. Farrow Michael B. Levy Executive Director Washington, DC Samuel Gruber Rachmiel Liberman Research Director Brookline, MA Katrina A. Krzysztofiak Laura Raybin Miller Program Manager Pembroke Pines, FL Patricia Hoglund Vincent Obsitnik Administrative Officer McLean, VA 888 17th Street, N.W., Suite 1160 Washington, DC 20006 Ph: ( 202) 254-3824 Fax: ( 202) 254-3934 E-mail: [email protected] May 30, 2005 Message from the Chairman One of the principal missions that United States law assigns the Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad is to identify and report on cemeteries, monuments, and historic buildings in Central and Eastern Europe associated with the cultural heritage of U.S. citizens, especially endangered sites. The Congress and the President were prompted to establish the Commission because of the special problem faced by Jewish sites in the region: The communities that had once cared for the properties were annihilated during the Holocaust. -

Ukraine's Quest for Mature Nation Statehood

Ukraine’s Quest for Mature Nation Statehood By Vlad Spanu Oct. 01, 2015 Content Historical background Ethnics Romanians in Ukraine Ethnics Ukrainians in Romania and in the Republic of Moldova From challenge to opportunity Romanians in Ukraine 10th century: Slavic tribes (Ulichs and Tivertsy) from the north, Romanians (Vlachs) from the west, as well as Turkic nomads (Pechenegs, Cumans and later Tatars) from the east Since 14th century, the area were intermittently ruled by Lithuanian dukes, Polish kings, Crimean khans, and Moldavian princes (Ion Vodă Armeanul) In 1681 Gheorghe Duca's title was "Despot of Moldavia and Ukraine,” as he was simultaneously Prince of Moldavia and Hetman of Ukraine Other Moldavian princes who held control of the territory in 17th and 18th centuries were Ştefan Movilă, Dimitrie Cantacuzino and Mihai Racoviţă Renown Romanians among Cossacks Among the hetmans of the Cossacks: -1593–1596: Ioan Potcoavă, Grigore Lobodă (Hryhoriy Loboda) - 1659–1660: Ioan Sârcu (Ivan Sirko) - 1727–1734: DăniLă ApostoL (DanyLo ApostoL) - Others hetmans: Alexander Potcoavă, Constantin Potcoavă, Petre Lungu, Petre Cazacu, Tihon Baibuza, Samoilă Chişcă, Opară, Trofim VoLoşanin, Ion ŞărpiLă, Timotei Sgură, Dumitru Hunu Other high-ranking Cossacks: Polkovnyks Toader Lobădă and Dumitraşcu Raicea in PereyasLav-KhmeLnytskyy, Martin Puşcariu in Poltava, BurLă in Gdańsk, PaveL Apostol in Mirgorod, Eremie Gânju and Dimitrie Băncescu in Uman, VarLam BuhăţeL, Grigore GămăLie in Lubensk, Grigore Cristofor, Ion Ursu, Petru Apostol in Lubensk -

The Future Fund of the Republic of Austria Subsidizes Scientific And

The Future Fund of the Republic of Austria subsidizes scientific and pedagogical projects which foster tolerance and mutual understanding on the basis of a close examination of the sufferings caused by the Nazi regime on the territory of present-day Austria. Keeping alive the memory of the victims as a reminder for future generations is one of our main targets, as well as human rights education and the strengthening of democratic values. Beyond, you will find a list containing the English titles or brief summaries of all projects approved by the Future Fund since its establishment in 2006. For further information in German about the content, duration and leading institutions or persons of each project, please refer to the database (menu: “Projektdatenbank”) on our homepage http://www.zukunftsfonds-austria.at If you have further questions, please do not hesitate to contact us at [email protected] Project-Code P06-0001 brief summary Soviet Forced Labour Workers and their Lives after Liberation Project-Code P06-0002 brief summary Life histories of forced labour workers under the Nazi regime Project-Code P06-0003 brief summary Unbroken Will - USA - Tour 2006 (book presentations and oral history debates with Holocaust survivor Leopold Engleitner) Project-Code P06-0004 brief summary Heinrich Steinitz - Lawyer, Poet and Resistance Activist Project-Code P06-0006 brief summary Robert Quintilla: A Gaul in Danubia. Memoirs of a former French forced labourer Project-Code P06-0007 brief summary Symposium of the Jewish Museum Vilnius on their educational campaign against anti-Semitism and Austria's contribution to those efforts Project-Code P06-0008 brief summary Effective Mechanisms of Totalitarian Developments.