Bukovyna During Bohdan Khmelnytskyi's Campaigns In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TEKA Komisji Architektury, Urbanistyki I Studiów Krajobrazowych XV-2 2019

TEKA 2019, Nr 2 Komisji Architektury, Urbanistyki i Studiów Krajobrazowych Oddział Polskiej Akademii Nauk w Lublinie Revisited the localization of fortifications of the 18th century on the surroundings of village of Braha in Khmelnytsky region Oleksandr harlan https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1473-6417 [email protected] Department of Design and Reconstruction of the Architectural Environment, Prydniprovs’ka State Academy of Civil Engineering and Architecture Abstract: the results of the survey of the territories of the village Braga in the Khmelnytsky region, which is in close prox- imity to Khotyn Fortress, are highlighted in this article. A general description of the sources that has thrown a great deal of light on the fortifications of the left bank of the Dnister River opposite the Khotyn Fortress according to the modern land- scape, is presented. Keywords: monument, fortification, village of Braga, Khotyn fortress, Dnister River Relevance of research Today there is a lack of architectural and urban studies in the context of studying the history of the unique monument – the Khotyn Fortress. Only a few published works can be cited that cover issues of origin, existence of fortifications and it’s preservation. To take into comprehensive account of the specific conservation needs of the Khotyn Fortress, it was necessary to carry out appropriate research works (bibliographic, archival, cartographic, iconographic), including on-site surveys. During 2014−2015, the research works had been carried out by the Research Institute of Conservation Research in the context of the implementation of the Plan for the organization of the territory of the State. During the elaboration of historical sources from the history of the city of Khotyn and the Khotyn Fortress it was put a spotlight on a great number of iconographic materials, concerning the recording of the fortifica- tions of the New Fortress of the 18th-19th centuries. -

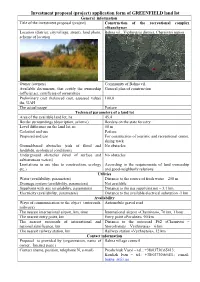

Investment Proposal (Project) Application Form of GREENFIЕLD

Investment proposal (project) application form of GREENFIЕLD land lot General information Title of the investment proposal (project) Construction of the recreational complex «Stanchyna» Location (district, city/village, street), land photo, Bahna vil., Vyzhnytsia district, Chernivtsi region scheme of location Owner (owners) Community of Bahna vil. Available documents, that certify the ownership General plan of construction (official act, certificate of ownership) Preliminary cost (balanced cost, assessed value) 100,0 ths. UAH The actual usage Pasture Technical parameters of a land lot Area of the available land lot, ha 45,4 Border surroundings (description, scheme) Borders on the state forestry Level difference on the land lot, m 50 m Cadastral end use Pasture Proposed end use For construction of touristic and recreational center, skiing track Ground-based obstacles (risk of flood and No obstacles landslide, ecological conditions) Underground obstacles (level of surface and No obstacles subterranean waters) Limitations in use (due to construction, ecology According to the requirements of land ownership etc.) and good-neighborly relations Utilities Water (availability, parameters) Distance to the source of fresh water – 250 m Drainage system (availability, parameters) Not available Supplying with gas (availability, parameters) Distance to the gas supplying net – 3,1 km. Electricity (availability, parameters) Distance to the available electrical substation -1 km Availability Ways of communication to the object (autoroads, Automobile gravel -

The Khmelnytsky Uprising Was a Cossack Rebellion in Ukraine Between the Years 1648–1657 Which Turned Into a Ukrainian War of Liberation from Poland

The Khmelnytsky Uprising was a Cossack rebellion in Ukraine between the years 1648–1657 which turned into a Ukrainian war of liberation from Poland. Under the command of Hetman Bohdan Khmelnytsky , the Cossacks [warrior caste] allied with the Crimean Tatars, and the local peasantry, fought several battles against forces of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. The result was an eradication of the control of the Polish and their Jewish intermediaries. Between 1648 and 1656, tens of thousands of Jews—given the lack of reliable data, it is impossible to establish more accurate figures—were killed by the rebels, and to this day the Khmelnytsky uprising is considered by Jews to be one of the most traumatic events in their history . The losses inflicted on the Jews of Poland during the fatal decade 1648-1658 were appalling. In the reports of the chroniclers, the number of Jewish victims varies between one hundred thousand and five hundred thousand…even exceeding the catastrophes of the Crusades and the Black Death in Western Europe. Some seven hundred Jewish communities in Poland had suffered massacre and pillage . In the Ukrainian cities situated on the left banks of the Dnieper, the region populated by Cossacks... the Jewish communities had disappeared almost completely . In 1 the localities on the right shore of the Dneiper or in the Polish part of the Ukraine as well as those of Volhynia and Podolia, wherever Cossacks had made their appearance, only about one tenth of the Jewish population survived . http://www.holocaust-history.org/questions/ukrainians.shtml Our research shows that a significant portion of the Ukrainian population voluntarily cooperated with the invaders of their country and voluntarily assisted in the Holocaust. -

The Role of Bohdan Khmelnytskyi and the Kozaks in the Rusin Struggle for Independence from the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth: 1648--1649

University of Windsor Scholarship at UWindsor Electronic Theses and Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, and Major Papers 1-1-1967 The role of Bohdan Khmelnytskyi and the Kozaks in the Rusin struggle for independence from the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth: 1648--1649. Andrew B. Pernal University of Windsor Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd Recommended Citation Pernal, Andrew B., "The role of Bohdan Khmelnytskyi and the Kozaks in the Rusin struggle for independence from the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth: 1648--1649." (1967). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 6490. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd/6490 This online database contains the full-text of PhD dissertations and Masters’ theses of University of Windsor students from 1954 forward. These documents are made available for personal study and research purposes only, in accordance with the Canadian Copyright Act and the Creative Commons license—CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution, Non-Commercial, No Derivative Works). Under this license, works must always be attributed to the copyright holder (original author), cannot be used for any commercial purposes, and may not be altered. Any other use would require the permission of the copyright holder. Students may inquire about withdrawing their dissertation and/or thesis from this database. For additional inquiries, please contact the repository administrator via email ([email protected]) or by telephone at 519-253-3000ext. 3208. THE ROLE OF BOHDAN KHMELNYTSKYI AND OF THE KOZAKS IN THE RUSIN STRUGGLE FOR INDEPENDENCE FROM THE POLISH-LI'THUANIAN COMMONWEALTH: 1648-1649 by A ‘n d r e w B. Pernal, B. A. A Thesis Submitted to the Department of History of the University of Windsor in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Faculty of Graduate Studies 1967 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

Did Authorities Crush Russian Orthodox Church Abroad Parish?

FORUM 18 NEWS SERVICE, Oslo, Norway http://www.forum18.org/ The right to believe, to worship and witness The right to change one's belief or religion The right to join together and express one's belief This article was published by F18News on: 4 October 2005 UKRAINE: Did authorities crush Russian Orthodox Church Abroad parish? By Felix Corley, Forum 18 News Service <http://www.forum18.org> Archbishop Agafangel (Pashkovsky) of the Odessa Diocese of the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad (ROCA) has told Forum 18 News Service that the authorities in western Ukraine have crushed a budding parish of his church, at the instigation of Metropolitan Onufry, the diocesan bishop of the rival Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate. The head of the village administration, Vasyl Gavrish, denies claims that he threatened parishioners after the ROCA parish submitted a state registration application. When asked by Forum 18 whether an Orthodox church from a non-Moscow Patriarchate jurisdiction could gain registration, Gavrish replied: "We already have a parish of the Moscow Patriarchate here." Both Gavrish and parishioners have stated that the state SBU security service was involved in moves against the parish, but the SBU has denied this along with Bishop Agafangel's claim that there was pressure from the Moscow Patriarchate. Archbishop Agafangel (Pashkovsky) of the Odessa Diocese of the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad (ROCA) has accused the authorities of crushing a budding parish of his church, in the small village of Grozintsy in Khotin [Khotyn] district of Chernivtsy [Chernivtsi] region, in western Ukraine bordering Romania. "People were afraid of the authorities' threats and withdrew their signatures on the parish's registration application," he told Forum 18 News Service from Odessa on 27 September. -

From Region to Region 15-Day Tour to the Most Intriguing Places of Ancient

Ukraine: from region to region 15-day tour to the most intriguing places of ancient Ukraine All year round Explore the most interesting sights all over Ukraine and learn about the great history of the country. Be dazzled by glittering church domes, wide boulevards and glamorous nightlife in Kyiv, the capital city; learn about the Slavonic culture in Chernihiv and dwell on the Cossacks epoch at the other famous towns; admire the palace and park complexes, imagining living in the previous centuries; disclose the secrets of Ukrainian unique handicrafts and visit the magnificent monasteries. Don’t miss a chance to drink some coffee in the well-known and certainly stunning Western city Lviv and take an opportunity to see the beautiful Carpathian Mountains, go hiking on their highest peak or just go for a stroll in the truly fresh air. Get unforgettable memories from Kamyanets-Podilsky with its marvelous stone fortress and take pictures of the so called “movie-star fortress” at Khotyn. Day 1, Kyiv Meeting at the airport in Kyiv. Transfer to a hotel. Accommodation at the hotel. Welcome dinner. Meeting with a guide and a short presentation of a tour. Day 2, Kyiv Breakfast. A 3-hour bus tour around the historical districts of Kyiv: Golden Gate (the unique monument which reflects the art of fortification of Kievan Rus), a majestic St. Sophia’s Cathedral, St. Volodymyr’s and St. Michael’s Golden Domed Cathedrals, an exuberant St. Andrew’s Church. A walk along Andriyivsky Uzviz (Andrew’s Descent) – Kyiv’s “Monmartre” - where the peculiar Ukrainian souvenirs may be bought. -

SITUATION with STUDYING the HISTORY of the UKRAINIAN COSSACK STATE USING the TURK-OTTOMAN SOURCES Ferhad TURANLY

Karadeniz İncelemeleri Dergisi: Yıl 8, Sayı 15, Güz 2013 205 SITUATION WITH STUDYING THE HISTORY OF THE UKRAINIAN COSSACK STATE USING THE TURK-OTTOMAN SOURCES Ferhad TURANLY ABSTRACT Available studies of the Turk-Ottoman sources on the history of Ukraine in the period of Cossacks have been presented and considered. The problem concerning development of the Oriental Studies has been analysed. There has been used a methodology that is a new contribution to the academic study of the issues relating to the history of the development of relations between the Cossack Hetman Ukraine and the Ottoman State. Keywords: Ottoman, Ukrainan, a Cossack, a study, oriental studies. OSMANLI-TÜRK KAYNAKLARINA GÖRE UKRAYNA KOZAK DÖNEMİ TARİH ÇALIŞMALARI ÖZ Bu makalede, Ukrayna Kozak dönemi tarihi hakkında Osmanlı zamanında ortaya çıkmış araştırmalar değerlendirilmiştir. Söz konusu kaynakların Ukrayna tarihi açısından ele alındığı araştırmada Şarkiyat biliminin gelişmesiyle iligili sorunlardan da bahsolunmaktadır. Uygun usullerin kullanılmasıyla, bu kaynakla- rın, Kazak Hetman Ukraynası ve Osmanlı Devleti arasındaki ilişki- lerin tarihinin derinliğinin öğrenilmesini sağlayacağı, araştırmada varılan temel sonuçlardan biridir. Anahtar Sözcükler: Araştırma, Şarkiyat, Kozak, Osmanlı, Ukrayna. A reader at Kyiv National University “Kyiv Mohyla Academy”, [email protected] 206 Journal of Black Sea Studies: Year 8, Number 15, Autumn 2013 In the source base on Ukraine’s History and Culture, in particular, concerning its Cossack-Hetman period, an important place belongs to a complex of Arabic graphic texts, as an important part of which we consider a series of Turk sources – written and other kinds of historical commemorative books and documents, whose authors originated from the countries populated by the Turk ethnic groups. -

The History of Ukraine Advisory Board

THE HISTORY OF UKRAINE ADVISORY BOARD John T. Alexander Professor of History and Russian and European Studies, University of Kansas Robert A. Divine George W. Littlefield Professor in American History Emeritus, University of Texas at Austin John V. Lombardi Professor of History, University of Florida THE HISTORY OF UKRAINE Paul Kubicek The Greenwood Histories of the Modern Nations Frank W. Thackeray and John E. Findling, Series Editors Greenwood Press Westport, Connecticut • London Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Kubicek, Paul. The history of Ukraine / Paul Kubicek. p. cm. — (The Greenwood histories of the modern nations, ISSN 1096 –2095) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978 – 0 –313 – 34920 –1 (alk. paper) 1. Ukraine —History. I. Title. DK508.51.K825 2008 947.7— dc22 2008026717 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available. Copyright © 2008 by Paul Kubicek All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2008026717 ISBN: 978– 0– 313 – 34920 –1 ISSN: 1096 –2905 First published in 2008 Greenwood Press, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. www.greenwood.com Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this book complies with the Permanent Paper Standard issued by the National Information Standards Organization (Z39.48 –1984). 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Every reasonable effort has been made to trace the owners of copyright materials in this book, but in some instances this has proven impossible. -

Jewish Cemetries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine

Syracuse University SURFACE Religion College of Arts and Sciences 2005 Jewish Cemetries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine Samuel D. Gruber United States Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/rel Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Gruber, Samuel D., "Jewish Cemeteries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine" (2005). Full list of publications from School of Architecture. Paper 94. http://surface.syr.edu/arc/94 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts and Sciences at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Religion by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JEWISH CEMETERIES, SYNAGOGUES, AND MASS GRAVE SITES IN UKRAINE United States Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad 2005 UNITED STATES COMMISSION FOR THE PRESERVATION OF AMERICA’S HERITAGE ABROAD Warren L. Miller, Chairman McLean, VA Members: Ned Bandler August B. Pust Bridgewater, CT Euclid, OH Chaskel Besser Menno Ratzker New York, NY Monsey, NY Amy S. Epstein Harriet Rotter Pinellas Park, FL Bingham Farms, MI Edgar Gluck Lee Seeman Brooklyn, NY Great Neck, NY Phyllis Kaminsky Steven E. Some Potomac, MD Princeton, NJ Zvi Kestenbaum Irving Stolberg Brooklyn, NY New Haven, CT Daniel Lapin Ari Storch Mercer Island, WA Potomac, MD Gary J. Lavine Staff: Fayetteville, NY Jeffrey L. Farrow Michael B. Levy Executive Director Washington, DC Samuel Gruber Rachmiel -

The Residence of Bukovyna and Dalmatia Metropolitans in Chernivtsi

THE RESIDENCE OF BUKOVYNA AND DALMATIA METROPOLITANS IN CHERNIVTSI NOMINATION BY THE GOVERNMENT OF UKRAINE OF THE FOR INSCRIPTION THE RESIDENCE OF BUKOVYNA AND DALMATIA METROPOLITANS I N CHERNIVTSI ON THE WORLD HERITAGE LIST 2008 PREPARED BY GOVERNMENT OF UKRAINE, STATE AND LOCAL AUTHORITIES AND THE ACADEMIC COUNCIL OF YURIJ FEDKOVYCH NATIONAL UNIVERSITY TABLE OF CONTENTS Summery…………………………………………………………………………..…5 1. IDENTIFICATION OF THE PROPERTY 1.A Country . …... 16 1.B State, province or region . …………..…18 1.C Name of property . …….….19 1.D Geographical coordinates to the nearest second. Property description . ……. 19 1.E Maps and plans . ………...20 1.F Area of nominated property and proposed buffer zone . .. … . ..22 2. DESCRIPTION 2.A Description of property . ………........26 2.B History and development . .………………..38 3. JUSTIFICATION FOR INSCRIPTION 3.A Criteria under which inscription is proposed and justifi cation for inscription 48 3.B Proposed statement of outstanding universal value . 54 3.C Comparative analysis . 55 3.D Integrity and authenticity . 75 4. STATE OF CONSERVATION AND FACTORS AFFECTING THE PROPERTY 4.A Present state of conservation . .79 4.B Factors affecting the property . 79 (i) Development pressures . 80 (ii) Environmental pressures . 80 (iii) Natural disasters and risk preparedness . 80 (iv) Visitor/tourism pressures . 81 (v) Number of inhabitants within the property and the buffer zone . .. 87 5. PROTECTION AND MANAGEMENT OF THE PROPERTY 5.A Ownership . 90 5.B Protective designation . 98 5.C Means of implementing protective measures . 110 5.D Existing plans related to municipality and region in which the proposed property is located . 111 5.E Property management plan or other management system . -

NARRATING the NATIONAL FUTURE: the COSSACKS in UKRAINIAN and RUSSIAN ROMANTIC LITERATURE by ANNA KOVALCHUK a DISSERTATION Prese

NARRATING THE NATIONAL FUTURE: THE COSSACKS IN UKRAINIAN AND RUSSIAN ROMANTIC LITERATURE by ANNA KOVALCHUK A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department of Comparative Literature and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy June 2017 DISSERTATION APPROVAL PAGE Student: Anna Kovalchuk Title: Narrating the National Future: The Cossacks in Ukrainian and Russian Romantic Literature This dissertation has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in the Department of Comparative Literature by: Katya Hokanson Chairperson Michael Allan Core Member Serhii Plokhii Core Member Jenifer Presto Core Member Julie Hessler Institutional Representative and Scott L. Pratt Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded June 2017 ii © 2017 Anna Kovalchuk iii DISSERTATION ABSTRACT Anna Kovalchuk Doctor of Philosophy Department of Comparative Literature June 2017 Title: Narrating the National Future: The Cossacks in Ukrainian and Russian Romantic Literature This dissertation investigates nineteenth-century narrative representations of the Cossacks—multi-ethnic warrior communities from the historical borderlands of empire, known for military strength, pillage, and revelry—as contested historical figures in modern identity politics. Rather than projecting today’s political borders into the past and proceeding from the claim that the Cossacks are either Russian or Ukrainian, this comparative project analyzes the nineteenth-century narratives that transform pre- national Cossack history into national patrimony. Following the Romantic era debates about national identity in the Russian empire, during which the Cossacks become part of both Ukrainian and Russian national self-definition, this dissertation focuses on the role of historical narrative in these burgeoning political projects. -

CUPP Newsletter Fall 2017

CANADA-UKRAINE PARLIAMENTARY PROGRAM ПАРЛЯМЕНТАРНА ПРОГРАМА КАНАДА-УКРАЇНА PROGRAMME PARLAMENTAIRE CANADA-UKRAINE NEWSLETTER 2017 Contents About CUPP On July 16, 1990, the Supreme celebrate this milestone in Canada’s 4 CUPP Director’s article Soviet of the Ukrainian SSR adopt- history. 5 CUPP 2017 BIOs ed the Declaration of Sovereign- The Chair of Ukrainian Studies ty, which declared that Parliament Foundation of Toronto marked the Favourite Landscapes 14 recognized the need to build the Centennial by establishing the CAN- 32 Prominent MPs, Senators, Ukrainian state based on the Rule ADA-UKRAINE PARLIAMENTARY sports personalities of Law. PROGRAM (CUPP) for university On August 24, 1991, the Ukrainian students from Ukraine. CUPP gives 59 Вікно в Канаду Parliament adopted the Declaration Ukrainian students an opportunity 62 CUPP KIDS of Independence, which the citizens to work and study in Canada’s Par- of Ukraine endorsed in the refer- liament, and gain experience from 64 CUPP Newsletter Front Covers endum of December 1, 1991. Also which generations of Canadian, in 1991, Canadians celebrated the American and West European stu- 66 CUPP celebrates Canada’s Centennial of Ukrainian group im- dents have benefited. 150th birthday migration to Canada. To mark the On the basis of academic excel- 68 CUPP Universities Centennial, Canadian organizations lence, knowledge of the English or planned programs and projects to French and Ukrainian languages, Contact Us People who worked on this issue: Chair of Ukrainian Studies Iryna Hrechko, Lucy Hicks, Yuliia Serbenenko, Anna Mysyshyn, Foundation Ihor Bardyn. 620 Spadina Avenue Toronto, Ontario, Canada M5S 2H4 Front cover collage: Anna Mysyshyn. Tel: (416) 234-9111 Layout design: Yuliia Serbenenko.