Cerulean Warbler Has Been Little Studied; Management Actions to Enhance Its Habitat Have Not Yet Been Specified

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Red-Breasted Nuthatch and Golden-Crowned Kinglet

Red-breasted Nuthatch and Golden-crowned Kinglet: The First Nests for South Carolina and Other Chattooga Records Frank Renfrow 611 South O’Fallon Avenue, Bellevue, KY 41073 [email protected] Introduction The Chattooga Recreation Area (referred to as CRA for purposes of this article), located adjacent to the Walhalla National Fish Hatchery (780 m) within Sumter National Forest, Oconee Co., South Carolina, has long been noted as a unique natural area within the state. The picnic area in particular, situated along the East Fork of the Chattooga River, contains an old-growth stand of White Pine (Pinus strobus) and Canada Hemlock (Tsuga canadensis) with state records for both species as well as an impressive understory of Mountain Laurel (Kalmia latifolia) and Great Laurel (Rhododendron maximum) (Gaddy 2000). Nesting birds at CRA not found outside of the northwestern corner of the state include Black-throated Blue Warbler (Dendroica caerulescens) and Dark-eyed Junco (Junco hyemalis). Breeding evidence of two other species of northern affinities, Red-breasted Nuthatch (Sitta canadensis) and Golden-crowned Kinglet (Regulus satrapa) has previously been documented at this location (Post and Gauthreaux 1989, Oberle and Forsythe 1995). However, nest records of these two species have not been documented prior to this study. The summer occurrence of two other northern species on the South Carolina side of the Chattooga River, Brown Creeper (Certhia americana) and Winter Wren (Troglodytes troglodytes) has not been previously recorded. Only a few summer records of the Blackburnian Warbler (Dendroica fusca) have been noted for the state. Extensive field observations were made by the author in the Chattooga River area of Georgia and South Carolina during the breeding seasons of 2000, 2002 and 2003 in order to verify breeding of bird species of northern affinities. -

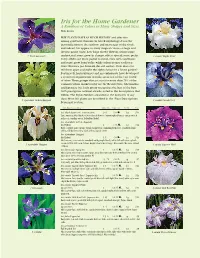

Iris for the Home Gardener a Rainbow of Colors in Many Shapes and Sizes Bob Lyons

Iris for the Home Gardener A Rainbow of Colors in Many Shapes and Sizes Bob Lyons FEW PLANTS HAVE AS MUCH HISTORY and affection among gardeners than iris. In Greek mythology, Iris is the personification of the rainbow and messenger of the Gods, and indeed, Iris appear in many magical colors—a large and diverse genus. Some have large showy flowers, others more I. ‘Black Gamecock’ understated; some grow in clumps, others spread; some prefer I. ensata ‘Angelic Choir’ it dry, others are more partial to moist, even wet conditions; and some grow from bulbs, while others return each year from rhizomes just beneath the soil surface. How does one tell them apart and make the right choice for a home garden? Fortunately, horticulturists and iris enthusiasts have developed a system of organization to make sense out of the vast world of irises. Three groups that account for more than 75% of the commercial iris market today are the Bearded Iris, Siberian Iris, and Japanese Iris. Each group recognizes the best of the best with prestigious national awards, noted in the descriptions that follow. The Dykes Medal is awarded to the finest iris of any class. More iris plants are described in the “Plant Descriptions: I. ×pseudata ‘Aichi no Kagayaki’ I. ensata ‘Cascade Crest’ Perennial” section. Latin Name Common Name Mature Size Light Soil Pot Size Price Iris ‘Black Gamecock’ Louisiana Iris 2–3 .8 d 1 g $14 Late; stunning blue black, velvet-colored flowers; hummingbird haven; can grow in 4 inches of standing water; DeBaillon Medal. Iris ×pseudata ‘Aichi no Kagayaki’ Iris Hybrid 2 . -

Cerulean Warbler Status Assessment April 2000

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Cerulean Warbler Status Assessment April 2000 Prepared by: For more information contact: Paul B. Hamel U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service U.S. Forest Service Nongame Bird Coordinator Southern Research Station Federal Building, 1 Federal Drive Box 227 Fort Snelling, MN 55111-4056 Stoneville, MS 38776 CERULEAN WARBLER STATUS ASSESSMENT Prepared by: Paul B. Hamel U. S. Forest Service Southern Research Station Box 227 Stoneville, MS 38776 April 2000 i TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES AND FIGURES........................................ v DISCLAIMER....................................................... vii SUMMARY......................................................... vii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS................................................ x 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................... 1 2. TAXONOMY ...................................................... 1 3. PHYSICAL DESCRIPTION........................................... 2 4. RANGE .......................................................... 2 4.1. Breeding Range ............................................. 3 4.2. Non-breeding Range ......................................... 3 4.2.1 Belize .............................................. 4 4.2.2 Bolivia.............................................. 4 4.2.3 Colombia............................................ 4 4.2.4 Costa Rica........................................... 4 4.2.5 Ecuador ............................................. 5 4.2.6 Guatemala........................................... 5 4.2.7 Honduras -

Development of a Genetic Multicolor Cell Labeling Approach for Neural

Development of a genetic multicolor cell labeling approach for neural circuit analysis in Drosophila Dafni Hadjieconomou January 2013 Division of Molecular Neurobiology MRC National Institute for Medical Research The Ridgeway Mill Hill, London NW7 1AA U.K. Department of Cell and Developmental Biology University College London A thesis submitted to the University College London for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Declaration of authenticity This work has been completed in the laboratory of Iris Salecker, in the Division of Molecular Neurobiology at the MRC National Institute for Medical Research. I, Dafni Hadjieconomou, declare that the work presented in this thesis is the result of my own independent work. Any collaborative work or data provided by others have been indicated at respective chapters. Chapters 3 and 5 include data generated and kindly provided by Shay Rotkopf and Iris Salecker as indicated. 2 Acknowledgements I would like to express my utmost gratitude to my supervisor, Iris Salecker, for her valuable guidance and support throughout the entire course of this PhD. Working with you taught me to work with determination and channel my enthusiasm in a productive manner. Thank you for sharing your passion for science and for introducing me to the colourful world of Drosophilists. Finally, I must particularly express my appreciation for you being very understanding when times were difficult, and for your trust in my successful achieving. Many thanks to my thesis committee, Alex Gould, James Briscoe and Vassilis Pachnis for their quidance during this the course of this PhD. I am greatly thankful to all my colleagues and friends in the lab. -

Ecology, Morphology, and Behavior in the New World Wood Warblers

Ecology, Morphology, and Behavior in the New World Wood Warblers A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Brandan L. Gray August 2019 © 2019 Brandan L. Gray. All Rights Reserved. 2 This dissertation titled Ecology, Morphology, and Behavior in the New World Wood Warblers by BRANDAN L. GRAY has been approved for the Department of Biological Sciences and the College of Arts and Sciences by Donald B. Miles Professor of Biological Sciences Florenz Plassmann Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 ABSTRACT GRAY, BRANDAN L., Ph.D., August 2019, Biological Sciences Ecology, Morphology, and Behavior in the New World Wood Warblers Director of Dissertation: Donald B. Miles In a rapidly changing world, species are faced with habitat alteration, changing climate and weather patterns, changing community interactions, novel resources, novel dangers, and a host of other natural and anthropogenic challenges. Conservationists endeavor to understand how changing ecology will impact local populations and local communities so efforts and funds can be allocated to those taxa/ecosystems exhibiting the greatest need. Ecological morphological and functional morphological research form the foundation of our understanding of selection-driven morphological evolution. Studies which identify and describe ecomorphological or functional morphological relationships will improve our fundamental understanding of how taxa respond to ecological selective pressures and will improve our ability to identify and conserve those aspects of nature unable to cope with rapid change. The New World wood warblers (family Parulidae) exhibit extensive taxonomic, behavioral, ecological, and morphological variation. -

Avian Predation in a Declining Outbreak Population of the Spruce Budworm, Choristoneura Fumiferana (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae)

insects Article Avian Predation in a Declining Outbreak Population of the Spruce Budworm, Choristoneura fumiferana (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae) Jacques Régnière 1,* , Lisa Venier 2 and Dan Welsh 3,† 1 Natural Resources Canada, Canadian Forest Service, Laurentian Forestry Centre, 1055 rue du PEPS, Quebec City, QC G1V 4C7, Canada 2 Natural Resources Canada, Canadian Forest Service, Great Lakes Forestry Centre, 1219 Queen St. E., Sault Ste. Marie, ON P6A 2E5, Canada; [email protected] 3 Environment and Climate Change Canada, Canadian Wildlife Service, Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3, Canada * Correspondence: [email protected] † Deceased. Simple Summary: Cages preventing access to birds were used to measure the rate of predation by birds in a spruce budworm population during the decline of an outbreak. Three species of budworm-feeding warblers were involved in this predation on larvae and pupae. It was found that bird predation is a very important source of mortality in declining spruce budworm populations, and that bird foraging behavior changes as budworm prey become rare at the end of the outbreak. Abstract: The impact of avian predation on a declining population of the spruce budworm, Cho- ristoneura fumifereana (Clem.), was measured using single-tree exclosure cages in a mature stand of balsam fir, Abies balsamea (L.), and white spruce, Picea glauca (Moench.) Voss. Bird population Citation: Régnière, J.; Venier, L.; censuses and observations of foraging and nest-feeding activity were also made to determine the Welsh, D. Avian Predation in a response of budworm-linked warblers to decreasing food availability. Seasonal patterns of foraging. Declining Outbreak Population of the as well as foraging success in the declining prey population was compared to similar information Spruce Budworm, Choristoneura from birds observed in another stand where the spruce budworm population was rising. -

The Birds of New York State

__ Common Goldeneye RAILS, GALLINULES, __ Baird's Sandpiper __ Black-tailed Gull __ Black-capped Petrel Birds of __ Barrow's Goldeneye AND COOTS __ Little Stint __ Common Gull __ Fea's Petrel __ Smew __ Least Sandpiper __ Short-billed Gull __ Cory's Shearwater New York State __ Clapper Rail __ Hooded Merganser __ White-rumped __ Ring-billed Gull __ Sooty Shearwater __ King Rail © New York State __ Common Merganser __ Virginia Rail Sandpiper __ Western Gull __ Great Shearwater Ornithological __ Red-breasted __ Corn Crake __ Buff-breasted Sandpiper __ California Gull __ Manx Shearwater Association Merganser __ Sora __ Pectoral Sandpiper __ Herring Gull __ Audubon's Shearwater Ruddy Duck __ Semipalmated __ __ Iceland Gull __ Common Gallinule STORKS Sandpiper www.nybirds.org GALLINACEOUS BIRDS __ American Coot __ Lesser Black-backed __ Wood Stork __ Northern Bobwhite __ Purple Gallinule __ Western Sandpiper Gull FRIGATEBIRDS DUCKS, GEESE, SWANS __ Wild Turkey __ Azure Gallinule __ Short-billed Dowitcher __ Slaty-backed Gull __ Magnificent Frigatebird __ Long-billed Dowitcher __ Glaucous Gull __ Black-bellied Whistling- __ Ruffed Grouse __ Yellow Rail BOOBIES AND GANNETS __ American Woodcock Duck __ Spruce Grouse __ Black Rail __ Great Black-backed Gull __ Brown Booby __ Wilson's Snipe __ Fulvous Whistling-Duck __ Willow Ptarmigan CRANES __ Sooty Tern __ Northern Gannet __ Greater Prairie-Chicken __ Spotted Sandpiper __ Bridled Tern __ Snow Goose __ Sandhill Crane ANHINGAS __ Solitary Sandpiper __ Least Tern __ Ross’s Goose __ Gray Partridge -

Cerulean Warbler (Dendroica Cerulea)

COSEWIC Assessment and Update Status Report on the Cerulean Warbler Dendroica cerulea in Canada SPECIAL CONCERN 2003 COSEWIC COSEPAC COMMITTEE ON THE STATUS OF COMITÉ SUR LA SITUATION ENDANGERED WILDLIFE DES ESPÈCES EN PÉRIL IN CANADA AU CANADA COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC 2003. COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the Cerulean Warbler Dendroica cerulea in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vii + 25 pp. Previous report: McCracken, J.D. 1993. COSEWIC status report on the Cerulean Warbler Dendroica cerulea in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 34 pp. Production note: COSEWIC would like to acknowledge Jennifer J. Barg, Jason Jones and Raleigh J. Robertson for writing the update status report on the Cerulean Warbler Dendroica cerulea, prepared under contract with Environment Canada. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: (819) 997-4991 / (819) 953-3215 Fax: (819) 994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Ếgalement disponible en français sous le titre Évaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur la situation de la paruline azurée (Dendroica cerulea) au Canada – Mise à jour. Cover illustration: Cerulean Warbler — Photo courtesy of Jason Jones. Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada 2003 Catalogue No.CW69-14/218-2003E-IN ISBN 0-662-34119-8 Recycled paper COSEWIC Assessment Summary Assessment Summary – May 2003 Common name Cerulean Warbler Scientific name Dendroica cerulea Status Special Concern Reason for designation This species breeds in mature deciduous forests in southern Ontario and southwestern Quebec, a habitat which has disappeared from much of its Canadian range in the last 200 years. -

Bird-Species-And-Habitat-A.Pdf

[ Birds Component l Introduction Please note that this section and the Birds Appendix, excluding the habitat map, are copyright protected (Copyright© Ryan Mays, 2013. All rights reserved). Ryan Mays was very generous with his time and expertise in drafting material for the purposes of this conservation pion in the fall of 201 3. This section lists priority bird species documented on the property. The Birds Appendix describes all bird species known by the author to have been recorded at Mountain lake and the immediate vicinity. The Appendix also includes o References section for all citations found in this section and in the Birds Appendix. The Mountain lake Conservancy and lodge property (the property) is characterized by high el1vation forests that support diverse biotic communities similar to those in Canada and the northern United States. Bird populations on Salt Pond Mountain ore closely associated with topographical and altitudinal variation and hove been studied there and in other parts of the Mountain lake region for over a century by many observers (e.g. Kessler and Larner 1984; Johnston 2000). Although much of the region was logged starting around the turn of the nineteenth century, small tracts of the or.iginol forest escaped destruction and hove remained relatively undisturbed into modern times. The range in elevation of approximately 600m between the summit and base of Solt Pond Mountain allows for much diversity in both floral and faunal communities including the birds described in this pion. Bird Habits on the Property Ryon Mays identifies four general • ?~.)/· ■ types of bird habitat on the • ' "'4 • property. -

Checklist of Amphibians, Reptiles, Birds and Mammals of New York

CHECKLIST OF AMPHIBIANS, REPTILES, BIRDS AND MAMMALS OF NEW YORK STATE Including Their Legal Status Eastern Milk Snake Moose Blue-spotted Salamander Common Loon New York State Artwork by Jean Gawalt Department of Environmental Conservation Division of Fish and Wildlife Page 1 of 30 February 2019 New York State Department of Environmental Conservation Division of Fish and Wildlife Wildlife Diversity Group 625 Broadway Albany, New York 12233-4754 This web version is based upon an original hard copy version of Checklist of the Amphibians, Reptiles, Birds and Mammals of New York, Including Their Protective Status which was first published in 1985 and revised and reprinted in 1987. This version has had substantial revision in content and form. First printing - 1985 Second printing (rev.) - 1987 Third revision - 2001 Fourth revision - 2003 Fifth revision - 2005 Sixth revision - December 2005 Seventh revision - November 2006 Eighth revision - September 2007 Ninth revision - April 2010 Tenth revision – February 2019 Page 2 of 30 Introduction The following list of amphibians (34 species), reptiles (38), birds (474) and mammals (93) indicates those vertebrate species believed to be part of the fauna of New York and the present legal status of these species in New York State. Common and scientific nomenclature is as according to: Crother (2008) for amphibians and reptiles; the American Ornithologists' Union (1983 and 2009) for birds; and Wilson and Reeder (2005) for mammals. Expected occurrence in New York State is based on: Conant and Collins (1991) for amphibians and reptiles; Levine (1998) and the New York State Ornithological Association (2009) for birds; and New York State Museum records for terrestrial mammals. -

Widespread Warblers

Widespread Warblers Yellow Warbler (M) Yellow Warbler (F) Wilson’s Warbler (M) Wilson’s Warbler (F) Nashville Warbler Common Yellowthroat (M) Common Yellowthroat (F) Palm Warbler Yellow-rumped Yellow-rumped (Myrtle) Warbler (M) (Myrtle) Warbler (F) Orange-crowned Warbler Blackpoll Warbler (M) Blackpoll Warbler (F) Black-and-white Warbler (M) Black-and-white Warbler (F) Northern Waterthrush American Redstart (M) American Redstart (F) Yellow-breasted Chat Yellow Warbler male, Yellow Warbler female, Wilson's Warbler male, Common Yellowthroat male, Common Yellowthroat female, Palm Warbler, Yellow-rumped (Myrtle) Warbler male, Yellow-rumped (Myrtle) Warbler, Orange-crowned Warbler, Black and white Warbler male, Northern Waterthrush, American Redstart male, American Redstart female: Kevin J. McGowan, Wilson's Warbler female: Ian Routeley/ML29261821, Nashville Warbler: Benjamin Hack/ML70542021, Blackpoll Warbler male: Dick Dionne/ML38369491, Blackpoll Warbler female: Larry Sirvio/ML47600211, Black and White Warbler female: Peter Hawrylyshyn/ML80064421, Yellow-breasted Chat: Paul Aucoin/ML45134551 Eastern Warblers 1 Kentucky Warbler Prairie Warbler (M) Prairie Warbler (F) Hooded Warbler (M) Hooded Warbler (F) Pine Warbler (M) Pine Warbler (F) Kirtland's Warbler (M) Kirtland's Warbler (F) Prothonotary Warbler Blue-winged Warbler Northern Parula (M) Northern Parula (F) Golden-winged Warbler (M) Golden-winged Warbler (F) Yellow-throated Warbler Worm-eating Warbler Swainson's Warbler Louisiana Waterthrush Prairie Warbler male, Prairie Warbler female, -

Birds of Allerton Park

Birds of Allerton Park 2 Table of Contents Red-head woodpecker .................................................................................................................................. 5 Red-bellied woodpecker ............................................................................................................................... 6 Hairy Woodpecker ........................................................................................................................................ 7 Downy woodpecker ...................................................................................................................................... 8 Northern Flicker ............................................................................................................................................ 9 Pileated woodpecker .................................................................................................................................. 10 Eastern Meadowlark ................................................................................................................................... 11 Common Grackle......................................................................................................................................... 12 Red-wing blackbird ..................................................................................................................................... 13 Rusty blackbird ...........................................................................................................................................