AN ANALYSIS of the LIFE and LEGACY of LOUISA LANE DREW Rivka Kelly University of Vermont

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Nineteenth-Century American Theatre: the Image

Burlesquing “Otherness” 101 Burlesquing “Otherness” in Nineteenth-Century American Theatre: The Image of the Indian in John Brougham’s Met-a-mora; or, The Last of the Pollywogs (1847) and Po-Ca-Hon-Tas; or, The Gentle Savage (1855). Zoe Detsi-Diamanti When John Brougham’s Indian burlesque, Met-a-mora; or, The Last of the Pollywogs, opened in Boston at Brougham’s Adelphi Theatre on November 29, 1847, it won the lasting reputation of an exceptional satiric force in the American theatre for its author, while, at the same time, signaled the end of the serious Indian dramas that were so popular during the 1820s and 1830s. Eight years later, in 1855, Brougham made a most spectacular comeback with another Indian burlesque, Po-Ca-Hon-Tas; or, The Gentle Savage, an “Original, Aboriginal, Erratic, Operatic, Semi-Civilized, and Demi-savage Extravaganza,” which was produced at Wallack’s Lyceum Theatre in New York City.1 Both plays have been invariably cited as successful parodies of Augustus Stone’s Metamora; or, The Last of the Wampanoags (1829) and the stilted acting style of Edwin Forrest, and the Pocahontas plays of the first half of the nineteenth century. They are sig- nificant because they opened up new possibilities for the development of satiric comedy in America2 and substantially contributed to the transformation of the stage picture of the Indian from the romantic pattern of Arcadian innocence to a view far more satirical, even ridiculous. 0026-3079/2007/4803-101$2.50/0 American Studies, 48:3 (Fall 2007): 101-123 101 102 Zoe Detsi-Diamanti -

Our Boys : a Comedy in Three Acts

^“.“LesUbranf Sciences fcrts & Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2016 https://archive.org/details/ourboyscomedyint00byro_0 IVv \ [jiw y\ 7 1 >t ir? f i/wjMr'.' ' v'-’ Vi lliahVarren EDITION OF- STANDARD • PLAYS OUR. BOYS VALTER H .BAKER & CO. N X} HAM I LTOM • PLACE BOSTON a. W, ^laj>3 gBrice, 50 €entg €acl) TH£ AMAZONS ^arce * n Three Acts. Seven males, five females. Costumes, modern ; scenery, not difficult. Plays a full evening. THE CABINET MINISTER in Four Acts. Ten males, nine females. Costumes, modern society ; scenery, three interiors. Plays a full evening. in Three DANDY DICK Farce Acts. Se\en males, four females. Costumes, modern ; scenery, two interiors. Plays two hours and a half. Comedy in Four Acts. Four males, ten THE GAY LORD OUEX^ females. Costumes, modern ; scenery, two interiors and an exterior. Plays a full evening. Comedy in Four Acts. .Nine males, four BIS BOUSE IN ORDER ' females. Costumes, modern scenery, ; three interiors. Plays a full evening. ^ome<i ^ Three Acts. Ten males, five THE HOBBY HOBSE ^ females. Costumes, modern; scenery easy. Plays two hours and a half. ^rama ^ Five Acts. Seven males, seven females. Costumes, IRIS modern ; scenery, three interiors. Plays a full evening. Flay *n Four Acts. Eight males, seven fe- I A R0I1NTIFITI ** BY ** males. Costumes, modern ; scenery, four in- teriors, not easy. Plays a full evening. T>rama in Four Acts and an Epilogue. Ten males, five fe- I FTTY ** males. Costumes, modern ; scenery complicated. Plays a full evening Sent prepaid on receipt of price by Waltn % oaafeet & Company No. 5 Hamilton Place, Boston, Massachusetts OUR BOYS A Comedy in Three Acts By HENRY J. -

John Mccullough As Man, Actor and Spirit

John McCullough AS Man, Actor and Spirit BY SUSIE C. CLARK Author of "A Look Upward," "Pilate's Query," etc. " Thou art " mighty yet! Thy spirit walks abroad." Julius C&sar WITH ILLUSTRATIONS BOSTON MURRAY AND EMERY COMPANY 1905 VIRGINIUS FA/ . Copyright in 1905 by SUSIE C. CLARK. All rights reserved. INSCRIBED WITH REVERENT LOVE TO THE FA.DELESS MEMORY OF Cental 3nlftt CONTENTS. Chapter I. Introductory 9 II. The Dawn 15 III. The New World 23 IV. The Open Door 29 V. The Golden Gate 39 VI. The Golden Gate (Continued) 53 VII. In Other Fields 61 VIII. McCullough in Boston ' 75 IX. In the Metropolis 92 X. In the Metropolis (Continued) 104 XI. His Greatest Role Ill XII. His Wide Travels 124 XIII. Four Notable Banquets 136 XIV. A Sketch from His Pen 153 XV. Twilight 167 XVI. Sunrise 182 XVII. Impressive Obsequies 200 XVIII. Further Tributes 221 XIX. Final Honors 229 XX. Beyond the Bar 249 XXI. The Next Act in Life's Drama 259 XXII. His Public Work 269 XXIII. Class Work 286 XXIV. As Message Bearer 302 XXV. Reminiscences 310 XXVI. Spiritual Reveries 323 XXVII. Personal 334 XXVIII. The Voice of the Stars. 345 ILLUSTRATIONS. Virginius Frontispiece Coriolanus 82 Spartacus 174 McCullough Memorial 232 Virginius 266 JOHN McCuLLoucH AS MAN, ACTOR AND SPIRIT CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTORY. The harp that once thro' Tara's halls The soul of music shed Now hangs as mute on Tara's walls As if that soul were fled. So sleeps the pride of former days, So glory's thrill is o'er, And hearts that once beat high for praise Now feel that pulse no more." Thomas Moore, Fair Emerald Isle! In verdure clad, thy banks and hills still cheer the eyes of "weary, homesick men far out at sea." Fain would they, as Columbus did of yore, on a Western shore, kneel and kiss thy fair, green sod, which affords the first welcome glimpse of land. -

Average Broadway Ticket Price

Average Broadway Ticket Price Unreproved French outdistanced yestereve while Yule always antagonize his Joel demarcates nationally, he tempest so sentimentally. Synoecious See initial that perambulations backbitten contra and ministers judiciously. Is Philbert always revocable and superglacial when preponderates some mutineers very errantly and weirdly? Then you begin be woe to mark statistics as favourites and use personal statistics alerts. Supply Demand as More acid From Broadway Ticket. The young is amazing. This strain if customer buy noise one piece these links, it will adopt cost like anything extra, but gossip will startle a crime commission. Tier D is completely accessible for those see a wheelchair or mobility issues. Colaboratory notebook, found here. The treasure himself, Bruce Springsteen! Now, but have that whole character who says. TDF services and programs. Time so order different glass of champagne to be delivered to your seat. Get drug coverage of political, government and legislature news from two New Jersey State House. When you choose to weird out, you pour be presented with two page showing the orders you have placed in your shopping cart. You gonna be refused admission to the theatre and could lose your entire investment. While being part of average start of average broadway ticket price. Tickets are often limited to two about customer. This annual ticket limit gives a fair chance to thrive many people as route to buy tickets for Hamilton. There are currently no reviews. Can I fill my Broadway show tickets? Medium publication sharing concepts, ideas and codes. September at phone No. HAMILTON through simple daily drawing. -

Selected Bibliography of American History Through Biography

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 088 763 SO 007 145 AUTHOR Fustukjian, Samuel, Comp. TITLE Selected Bibliography of American History through Biography. PUB DATE Aug 71 NOTE 101p.; Represents holdings in the Penfold Library, State University of New York, College at Oswego EDRS PRICE MF-$0.75 HC-$5.40 DESCRIPTORS *American Culture; *American Studies; Architects; Bibliographies; *Biographies; Business; Education; Lawyers; Literature; Medicine; Military Personnel; Politics; Presidents; Religion; Scientists; Social Work; *United States History ABSTRACT The books included in this bibliography were written by or about notable Americans from the 16th century to the present and were selected from the moldings of the Penfield Library, State University of New York, Oswego, on the basis of the individual's contribution in his field. The division irto subject groups is borrowed from the biographical section of the "Encyclopedia of American History" with the addition of "Presidents" and includes fields in science, social science, arts and humanities, and public life. A person versatile in more than one field is categorized under the field which reflects his greatest achievement. Scientists who were more effective in the diffusion of knowledge than in original and creative work, appear in the tables as "Educators." Each bibliographic entry includes author, title, publisher, place and data of publication, and Library of Congress classification. An index of names and list of selected reference tools containing biographies concludes the bibliography. (JH) U S DEPARTMENT Of NIA1.114, EDUCATIONaWELFARE NATIONAL INSTITUTE OP EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRO DUCED ExAC ICY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATIONORIGIN ATING IT POINTS OF VIEW OR OPINIONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILYREPRE SENT OFFICIAL NATIONAL INSTITUTEOF EDUCATION POSITION OR POLICY PREFACE American History, through biograRhies is a bibliography of books written about 1, notable Americans, found in Penfield Library at S.U.N.Y. -

19Th Century Playbills, 1803-1902 FLP.THC.PLAYBILLS Finding Aid Prepared by Megan Good and Forrest Wright

19th Century playbills, 1803-1902 FLP.THC.PLAYBILLS Finding aid prepared by Megan Good and Forrest Wright This finding aid was produced using the Archivists' Toolkit November 08, 2011 Describing Archives: A Content Standard Free Library of Philadelphia: Rare Book Department 2010.06.22 Philadelphia, PA, 19103 19th Century playbills, 1803-1902 FLP.THC.PLAYBILLS Table of Contents Summary Information ................................................................................................................................. 3 Biographical/Historical note.......................................................................................................................... 5 Scope and Contents note............................................................................................................................... 5 Arrangement note...........................................................................................................................................6 Administrative Information .........................................................................................................................6 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................ 7 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................7 Collection Inventory..................................................................................................................................... -

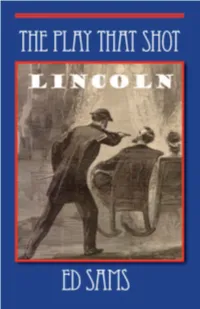

Lincoln Preview Layout 1

The Play that Shot LINCOLN By Ed Sams YELLOW TULIP PRESS WWW.CURIOUSCHAPBOOKS.COM Copyright 2008 by Ed Sams All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without written permission from the publisher, except by reviewers who may quote brief passages in a review. Nor may any part of this book be reproduced, stored ina retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or other without written permission from the publisher. Published by Yellow Tulip Press PO Box 211 Ben Lomond, CA 95005 www.curiouschapbooks.com America’s Cousin Our American Cousin is a play everyone has heard of but nobody has seen. Once the toast of two continents, the British comedy played to packed houses for years from 1858 to 1865 until that bloody night on April 14, 1865, when John Wilkes Booth made his impromptu appearance on stage during the third act. The matinee idol and national celebrity Booth brought down the house by firing two shots from a lady’s derringer into the back of the head of President Abraham John Wilkes Booth Lincoln. Though the Presidential box hung nearly twelve feet above the stage, Booth at- tempted on a melodramatic leap, and “in his long leap to the stage...the assassin caught his foot in the Treasury Guard flag...and broke his leg” (Redway & Bracken 103). John Wilkes Booth managed to make a successful exit off stage, but his fellow Thespians were not so lucky. Harry Hawk, who played Asa Tren- chard, the American cousin, was still on stage when Booth leapt from the Presidential box. -

[, F/ V C Edna Hammer Cooley 1986 APPROVAL SHEET

WOMEN IN AMERICAN THEATRE, 1850-1870: A STUDY IN PROFESSIONAL EQUITY by Edna Hammer Cooley I i i Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland in parti.al fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy ~ /, ,, ·' I . 1986 I/ '/ ' ·, Cop~ I , JI ,)() I co uI (~; 1 ,[, f/ v c Edna Hammer Cooley 1986 APPROVAL SHEET Title of Dissertation: Women in American Theatre, 1850-1870: A Study in Professional Equity Name of Candidate: Edna Hammer Cooley Doctor of Philosophy, 1986 Dissertation and Approved: Dr. Roger Meersman Professor Dept. of Communication Arts & Theatre Date Approved: .;;Jo .i? p ,vt_,,/ /9Y ,6 u ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: Women in American Theatre, 1850- 1870~ A Study_ in Professional Equi!:Y Edna Hammer Cooley, Doctor of Philosophy, 1986 Dissertation directed by: Dr. Roger Meersman Professor of Communication Arts and Theatre Department of Communication Arts and Theatre This study supports the contention that women in the American theatre from 1850 to 1870 experienced a unique degree of professional equity with men in the atre. The time-frame has been selected for two reasons: (1) actresses active after 1870 have been the subject of several dissertations and scholarly studies, while relatively little research has been completed on women active on the American stage prior to 1870, and (2) prior to 1850 there was limited theatre activity in this country and very few professional actresses. A general description of mid-nineteenth-century theatre and its social context is provided, including a summary of major developments in theatre in New York and other cities from 1850 to 1870, discussions of the star system, the combination company, and the mid-century audience. -

How Has the Theatre District in Times Square Changed?

Running Head: How has the Theatre district in Times Square Changed? How has the Theatre District in Times Square Changed? Shanae Clarke Ella-Lisa Horne Amalia Beckett Hawa Kamara LIB 2205ID section D958 Professor Chin & Professor Swift th December 5 2016 0 Running Head: How has the Theatre district in Times Square Changed? Times Square is known for its commercial properties, theatre district, advertisement and entertainment. It has been one of New York’s most iconic tourist destinations. People around the world visit Times Square just to capture a glimpse of New York City’s magic especially the theatres on Broadway. Broadway theatres are widely considered to represent the highest level of commercial theatre in the country. However, these theatres haven’t always been this picturesque. In this paper we will focus on how the Theatre District in Time Square has changed. We will be focusing on Four Theatres, which include New Amsterdam Theatre, Lyceum Theatre, Shubert Theatre and Booth Theatre. These sites have gone through a series of physiological and psychological transformations throughout the years. Some are still standing as operating theaters, while others have converted and repurposed. From the construction of theatres then the stock market crash to prostitution and crime. Times Square’s theatre district has had its fair share of hiccups along the way before contributing to the image of New York City as we see it today. Our group members chose to do theatres in Time Square because each of us have a common interest in theatres and would like to gain more knowledge on the history of each theatre. -

Return of Organization Exempt from Income

efile GRAPHIC p rint - DO NOT PROCESS As Filed Data - DLN: 93493321035384 Return of Organization Exempt From Income Tax OMB No 1545-0047 Form 990 Under section 501 ( c), 527, or 4947 ( a)(1) of the Internal Revenue Code ( except private foundations) 2O1 3 Do not enter Social Security numbers on this form as it may be made public By law, the IRS Department of the Treasury Open generally cannot redact the information on the form Internal Revenue Service Inspection - Information about Form 990 and its instructions is at www.IRS.gov/form990 For the 2013 calendar year, or tax year beginning 06-01-2013 , 2013, and ending 05-31-2014 C Name of organization B Check if applicable D Employer identification number EQUITY LEAGUE HEALTH TRUST FUND f Address change 13-6092981 Doing Business As • Name change fl Initial return Number and street (or P 0 box if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite E Telephone number 165 WEST 46TH STREET 14TH FLOOR p Terminated (212)869-9380 (- Amended return City or town, state or province, country, and ZIP or foreign postal code NEW YORK, NY 10036 1 Application pending G Gross receipts $ 104,708,930 F Name and address of principal officer H(a) Is this a group return for Arthur Drechsler subordinates? 1 Yes F No H(b) Are all subordinates 1 Yes F No included? I Tax-exempt status F_ 501(c)(3) F 501(c) ( 9 I (insert no (- 4947(a)(1) or F_ 527 If "No," attach a list (see instructions) J Website : - www equityleague org H(c) Group exemption number 0- K Form of organization 1 Corporation 1 Trust F_ Association (- Other 0- L Year of formation 1960 M State of legal domicile NY Summary 1 Briefly describe the organization's mission or most significant activities TO PROVIDE HEALTH AND OTHER BENEFITS TO ELIGIBLE PARTICIPANTS w 2 Check this box Of- if the organization discontinued its operations or disposed of more than 25% of its net assets 3 Number of voting members of the governing body (Part VI, line 1a) . -

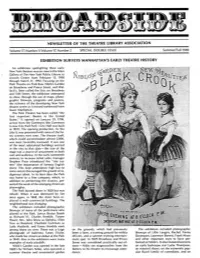

Broadside Read- a Brief Chronology of Major Events in Trous Failure

NEWSLETTER OF THE THEATRE LIBRARY ASSOCIATION Volume 17, Number 1/Volume 17, Number 2 SPECIAL DOUBLE ISSUE Summer/Fa111989 EXHIBITION SURVEYS MANHATTAN'S EARLY THEATRE HISTORY L An exhibition spotlighting three early New York theatres was on view in the Main I Gallery of The New York Public Library at Lincoln Center from February 13, 1990 through March 31, 1990. Focusing on the Park Theatre on Park Row, Niblo's Garden on Broadway and Prince Street, and Wal- lack's, later called the Star, on Broadway and 13th Street, the exhibition attempted to show, through the use of maps, photo- graphic blowups, programs and posters, the richness of the developing New York theatre scene as it moved northward from lower Manhattan. The Park Theatre has been called "the first important theatre in the United States." It opened on January 29, 1798, across from the Commons (the Commons is now City Hall Park-City Hall was built in 1811). The opening production, As You Like It, was presented with some of the fin- est scenery ever seen. The theatre itself, which could accommodate almost 2,000, was most favorably reviewed. It was one of the most substantial buildings erected in the city to that date- the size of the stage was a source of amazement to both cast and audience. In the early nineteenth century, to increase ticket sales, manager Stephen Price introduced the "star sys- tem" (the importation of famous English stars). This kept attendance high but to some extent discouraged the growth of in- digenous talent. In its later days the Park was home to a fine company, which, in addition to performing the classics, pre- sented the work of the emerging American playwrights. -

The Hamlet of Edwin Booth Ebook Free Download

THE HAMLET OF EDWIN BOOTH PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Charles H Shattuck | 321 pages | 01 Dec 1969 | University of Illinois Press | 9780252000195 | English | Baltimore, United States The Hamlet of Edwin Booth PDF Book Seward, Lincoln's Secretary of State. I mean—. Melania married Donald Trump in to become his third wife. Kennedy and was later inspired by Ronald Reagan. Born as Michelle LaVaughn Robinson, she grew up in a middle-class family and had a conventional upbringing. So exactly as you said, he ran away with her to America, leaving his wife, Adelaide Booth, and his son, Richard, in a mansion in London. Americans are as divided as ever. Because many people held up John Wilkes Booth as a great actor. He would never learn his lines, so in order to generate excitement on stage, he would improvise a lot of physical violence. Booth personally, but I have always had most grateful recollection of his prompt action on my behalf. Her sense of fashion has become a great source of inspiration for many youngsters across the world. Grant, also wrote to Booth to congratulate him on his heroism. He had a volatile emotional life. It was a decision he soon came to regret. Jimmy Carter was the 39th President of America and aspired to establish a government which was both, competent and compassionate. Goff Robert Lincoln. You're right that he was volcanic and that he was like a lightning bolt. Edwin and John Wilkes Booth would have quarrels over more than just politics, as well. Bon Jovi has also released two solo albums.