Our Boys : a Comedy in Three Acts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Return of Organization Exempt from Income

efile GRAPHIC p rint - DO NOT PROCESS As Filed Data - DLN: 93493321035384 Return of Organization Exempt From Income Tax OMB No 1545-0047 Form 990 Under section 501 ( c), 527, or 4947 ( a)(1) of the Internal Revenue Code ( except private foundations) 2O1 3 Do not enter Social Security numbers on this form as it may be made public By law, the IRS Department of the Treasury Open generally cannot redact the information on the form Internal Revenue Service Inspection - Information about Form 990 and its instructions is at www.IRS.gov/form990 For the 2013 calendar year, or tax year beginning 06-01-2013 , 2013, and ending 05-31-2014 C Name of organization B Check if applicable D Employer identification number EQUITY LEAGUE HEALTH TRUST FUND f Address change 13-6092981 Doing Business As • Name change fl Initial return Number and street (or P 0 box if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite E Telephone number 165 WEST 46TH STREET 14TH FLOOR p Terminated (212)869-9380 (- Amended return City or town, state or province, country, and ZIP or foreign postal code NEW YORK, NY 10036 1 Application pending G Gross receipts $ 104,708,930 F Name and address of principal officer H(a) Is this a group return for Arthur Drechsler subordinates? 1 Yes F No H(b) Are all subordinates 1 Yes F No included? I Tax-exempt status F_ 501(c)(3) F 501(c) ( 9 I (insert no (- 4947(a)(1) or F_ 527 If "No," attach a list (see instructions) J Website : - www equityleague org H(c) Group exemption number 0- K Form of organization 1 Corporation 1 Trust F_ Association (- Other 0- L Year of formation 1960 M State of legal domicile NY Summary 1 Briefly describe the organization's mission or most significant activities TO PROVIDE HEALTH AND OTHER BENEFITS TO ELIGIBLE PARTICIPANTS w 2 Check this box Of- if the organization discontinued its operations or disposed of more than 25% of its net assets 3 Number of voting members of the governing body (Part VI, line 1a) . -

Not Be Fouud by at Least Three of the Inspectors"

I j. f? 6 NEW YOEK HERALD, THURSDAt. OCTOBKK % Ib79..TKU'JLE SHEET. State in the election. d'Etat. self and for himself in a barrel all around Btinot.has been the of The New Folltieal Firm.Kelly, the equal advantages Mayor Coupor'n Coup outgrowth should have one-fourth of the circle, 'l'ho Herald at tbo time warned afforded tho Mr. Thomas and NEW YORK HERALD & Co. But if Tammany "It is the uuoxpocte 1 that happens," public by opportunities Cornellthe there would be least the and of all these bis ooluborors in this field of music during in the Police lioard inspectors virtually says a French proverb; bat among the proprietors supportors AND ANN STREET. The pending struggle three Cornell in each district that booms that they were making the post twenty years. Our German BROADWAY of of iuspeotors expected and most surprising tilings simply over the appointment inspector* one ltobinson sinoe the ridiculous and that each and every musical.have fostered and chief ugaiust inspector, could have happened is Mayor Cooper's themselves residents.largely continues to be the politicalelection and avowed of the vote one of them was marked for an kept alive in their homes the lovo of JAMES GORDON BENNETT, have solo purpose Kelly to remove from the Polioe Board hisattempt early grave. enough our uorr.ii:To». topic, although inspectors is to elect Cornell. own of Messrs. The first frost has scaroely come and tho old masters, and formed a to conduct the appointees, two whom, they been appointed legally The order of Barrett the and have been his servile prediction has been fulfilled. -

United States Theatre Programs Collection O-016

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8s46xqw No online items Inventory of the United States Theatre Programs Collection O-016 Liz Phillips University of California, Davis Library, Dept. of Special Collections 2017 1st Floor, Shields Library, University of California 100 North West Quad Davis, CA 95616-5292 [email protected] URL: https://www.library.ucdavis.edu/archives-and-special-collections/ Inventory of the United States O-016 1 Theatre Programs Collection O-016 Language of Material: English Contributing Institution: University of California, Davis Library, Dept. of Special Collections Title: United States Theatre Programs Collection Creator: University of California, Davis. Library Identifier/Call Number: O-016 Physical Description: 38.6 linear feet Date (inclusive): 1870-2019 Abstract: Mostly 19th and early 20th century programs, including a large group of souvenir programs. Researchers should contact Archives and Special Collections to request collections, as many are stored offsite. Scope and Contents Collection is mainly 19th and early 20th century programs, including a large group of souvenir programs. Access Collection is open for research. Processing Information Liz Phillips converted this collection list to EAD. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], United States Theatre Programs Collection, O-016, Archives and Special Collections, UC Davis Library, University of California, Davis. Publication Rights All applicable copyrights for the collection are protected under chapter 17 of the U.S. Copyright Code. Requests for permission to publish or quote from manuscripts must be submitted in writing to the Head of Special Collections. Permission for publication is given on behalf of the Regents of the University of California as the owner of the physical items. -

From the Tacoma, Is Taking a Brief Vacation

Columbia. Theatre in Longview, Wash. invasion of the phonograph has killed NUGGETS May 1926 (M) GEORGE Y AUNT, the hope of decent organ music in our organist of the Park Theatre in theatres for the present. When this new from the Tacoma, is taking a brief vacation. fad has been exploited a little, it is GOLDEN May 1926 (M) WILLIAM MASKE possible that some of the theatre is playing the Kimball in the D & R organists who have been committing Theatre in Aberdeen, Wash. unspeakable crimes against good Aug. 1926 (M) WEST BROWN and music, will mend their ways." JOHN McCOURTNEY are two of Tacoma's favorite organists, using a big GOLD DUST: 2/20 ALBERT HAY Wurlitzer in the Blue Mouse Theatre. MALOTTE at the Coliseum Theatre Oct. 1926 (J) HENRI A. KEATES, Wurlitzer in Seattle ... 10/23 GLENN who played several years at the Lib GOFF, Pantages and HENRI C LE erty Theatre in Portland, returned to BEL at the 2/9 Wurlitzer, Blue Mouse Chicago for a Mc Vickers Theatre en in Seattle ... 12/24 WILLIAM gagement. Keates has introduced com EVANS at Seattle Capitol's Kimball munity singi.ng, and it has become an ... 7 /25 ERNEST RUSSELL, Port outstanding feature. land's Liberty and DON ISHAM, Nov. 1926 (AO) OLIVER WAL Tacoma's Blue Mouse .. 12/25 CECIL LACE is playing the Wurlitzer in the TEAGUE, Majestic and ERNEST Prospected by Lloyd E. Klos Broadway Theatre in Portland. RUSSELL, Liberty in Portland Jan. 1927 (J) JAMES D. .. 4/26 SAMUEL P. TOTTEN, Next month, Portland, Ore. -

5Th Avenue Theatre Preview: Behind the Scenes of 'Bliss'

5th Avenue Theatre Preview: Behind the Scenes of 'Bliss' [00:00:05] Welcome to The Seattle Public Library’s podcasts of author readings and library events. To learn more about our events, programs and services visit w w w dot spl dot org. Library podcasts are brought to you by the Seattle Public Library Foundation to find out how you can support The Seattle Public Library visit supportspl dot org. [00:00:40] Thank you all for coming to this 5th Avenue Theatre preview presentation at The Seattle Public Library. My name is Bob Tangney, and I am the Music Librarian. I believe that’s it. So let me introduce Orlando Morales Director of Education and Engagement at 5th Avenue. [Applause] Thanks, Bob. [00:00:41] We are so excited to be back for another community conversation here at the Fifth Avenue here at the Seattle Public Library, which is very close to the Fifth Avenue Theatre. If you haven't been to the Fifth Avenue Theatre, I hope that you will join us for Bliss. We're just a couple blocks up Fifth Avenue and we're excited again to be here for another community conversation in partnership with the Seattle Public Library. I'd also like to thank a couple of show sponsors that we have for Bliss. We have the Edgerton Foundation, Boeing and Bank of America. [00:01:11] [Applause] Give it up for those sponsors. [00:01:14] Before we get started, I would like to acknowledge that we are on the traditional land of the first people of Seattle the Duwamish tribe, past and present and honor with gratitude the land itself and the Duwamish tribe. -

The New-York Historical Society Library Department of Prints, Photographs, and Architectural Collections

Guide to the Geographic File ca 1800-present (Bulk 1850-1950) PR20 The New-York Historical Society 170 Central Park West New York, NY 10024 Descriptive Summary Title: Geographic File Dates: ca 1800-present (bulk 1850-1950) Abstract: The Geographic File includes prints, photographs, and newspaper clippings of street views and buildings in the five boroughs (Series III and IV), arranged by location or by type of structure. Series I and II contain foreign views and United States views outside of New York City. Quantity: 135 linear feet (160 boxes; 124 drawers of flat files) Call Phrase: PR 20 Note: This is a PDF version of a legacy finding aid that has not been updated recently and is provided “as is.” It is key-word searchable and can be used to identify and request materials through our online request system (AEON). PR 000 2 The New-York Historical Society Library Department of Prints, Photographs, and Architectural Collections PR 020 GEOGRAPHIC FILE Series I. Foreign Views Series II. American Views Series III. New York City Views (Manhattan) Series IV. New York City Views (Other Boroughs) Processed by Committee Current as of May 25, 2006 PR 020 3 Provenance Material is a combination of gifts and purchases. Individual dates or information can be found on the verso of most items. Access The collection is open to qualified researchers. Portions of the collection that have been photocopied or microfilmed will be brought to the researcher in that format; microfilm can be made available through Interlibrary Loan. Photocopying Photocopying will be undertaken by staff only, and is limited to twenty exposures of stable, unbound material per day. -

THE PIRATES of PENZANCE Or, the Slave of Duty

Rediscover the NEW DATE! NEW TIME! NEW DATE! NEW TIME! NEW LOCATION! NEW FEATURES! NEW LOCATION! NEW FEATURES! SATURDAY, APRIL 14 SATURDAY,9 AM TO APRIL 3 PM 14 RIO CONVENTION9 AM TO 3 PM CENTER ATRIO THE CONVENTION RIO ALL-SUITE HOTEL CENTER & CASINO AT THE RIO ALL-SUITE HOTEL & CASINO The Las Vegas Review-Journal expands its annual AgeWell Expo for active The Las Vegas Review-Journal expands its annual AgeWell Expo for active adults 50+ with a travel and vacation festival featuring destinations, cruise adults 50+ with a travel and vacation festival featuring destinations, cruise lines, hotels, resorts, tours and airlines, all bringing attendees up to date on lines, hotels, resorts, tours and airlines, all bringing attendees up to date on the hottest travel offers and trends from around the world -- or just around the hottest travel offers and trends from around the world -- or just around the corner. Free travel seminars and award-winning travel consultants will the corner. Free travel seminars and award-winning travel consultants will provide the latest on travel tips for dream vacations in the state, region, provide the latest on travel tips for dream vacations in the state, region, nationally or internationally. nationally or internationally. FREE AND OPEN TO THE PUBLIC FREE AND OPEN TO THE PUBLIC SPONSOR AND EXHIBITOR SPONSOR AND EXHIBITOR OPPORTUNITIES AVAILABLE OPPORTUNITIESED CASSIDY, VP MARKETING AVAILABLE 702.383.4664ED CASSIDY, | [email protected] VP MARKETING 702.383.4664 | [email protected] agewellexpo.com agewellexpo.com NEW DATE! NEW TIME! NEW DATE! NEW TIME! NEW LOCATION! NEW FEATURES! UNLV NEW LOCATION! NEW FEATURES! presents Albert Bergeret, Artistic Director THE PIRATES OF PENZANCE or, The Slave of Duty SATURDAY, APRIL 14 SATURDAY,9 AM TO APRIL 3 PM 14 RIO CONVENTION9 AM TO 3 PM CENTER ATRIO THE CONVENTION RIO ALL-SUITE HOTEL CENTER & CASINO AT THE RIO ALL-SUITE HOTEL & CASINO Libretto by Sir William S. -

Journalistic Dramatic Criticism: a Survey of Theatre Reviews in New York, 1857-1927

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1939 Journalistic Dramatic Criticism: a Survey of Theatre Reviews in New York, 1857-1927. Louise Adams Blymyer Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Part of the Speech and Rhetorical Studies Commons Recommended Citation Blymyer, Louise Adams, "Journalistic Dramatic Criticism: a Survey of Theatre Reviews in New York, 1857-1927." (1939). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 7810. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/7810 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MANUSCRIPT THESES Unpublished theses submitted for the master*s and doctor’s degrees and deposited in the Louisiana State University Library are available for inspection. Use of any thesis is limited by the rights of the author. Bibliographical references may be noted* but passages may not be copied vinless the author has given permission# Credit must be given in subsequent written or published work# A library which borrows this thesis for use by its clientele is expected to make sure that the borrower is aware of the above res trictions « LOUISIANA STATE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 119-a JOURNAXISTIC DRAMATIC -

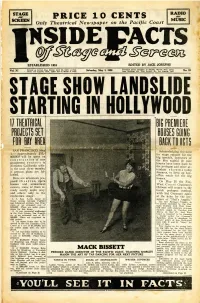

Inside Facts of Stage and Screen (May 3, 1930)

: STAGE RADIO SCREEN PRICE 10 CENTS MUSIC Only Theatrical Newspaper on the Pacific Coast ESTABLISHED 1S24 EDITED BY JACK JOSEPHS Entered as Second Class Matter, April 1927, at Post- Published Every Saturday at 800-801 Warner Bros. Down- Vol. XI 29, Saturday, May 3, 1930 No. 18 office, Los Angeles, Calif., under Act of March 3, 1879. town Building, 401 West Seventh St., Los Angeles, Calif. STAGE SHOW LANDSLIDE STARTING IN HOLLYWOOD 17 THEATRICAL Rie PREMIERE PROJECTS SET GtCKTD ACTS May SAN FRANCISCO, Acknowledging the need Approximately $15,- 1. — for stage support for the will be spent on 000,000 big specials, operators of of new construction the film capital de luxe amusement centers in houses have come back to Northern California with- the prologue and other at- in the next three months, tendant showman ship plans are fol- if present features, to keep up box- lowed. office totals for the big Here are seventeen pro- houses. posed theatres, opera On May 30 the Fox- houses and amusement West Coast Grauman’s centers, some of them al- Chinese will return to the ready nearly un^ler way, lavish prologue method, and others only in the with Sid Grauman again conference stage at the helm for the pre- 1. A Sam Levin house on miere of “Hell’s Angels.” Ocean avenue between Fairfield The new Pantages Theatre, and Lakewood avenues, San Fran- to be jointly operated by the Pan- cisco, at an estimated cost of tages brothers with West Coast, $250,000. Plans are under prepa- will start with elaborate prologue ration for this house. -

Dramatic Mirror, November 7, 1891, P. 8. 2. Helen Ten Broeck, “Rida Young—Dramatist and Garden Expert,” Theatre (April 1917): 202

NOTES INTRODUCTION 1. Ali Baba, “Mirror Interview: XXI—Martha Morton,” Dramatic Mirror, November 7, 1891, p. 8. 2. Helen Ten Broeck, “Rida Young—Dramatist and Garden Expert,” Theatre (April 1917): 202. 3. See Progressive Era at http://www.wikipedia.com. 4. Rachel Crothers (1878–1958), considered America’s first modern feminist playwright for her social comedies and woman-centered themes, is the only woman usually included within the “canon” of playwrights during the Progressive Era. Her production in 1906 of The Three of Us marked the beginning of a thirty-year career as a professional playwright and director in American theater. Her plays were well-constructed and dealt with pertinent issues of the time, such as the unfairness of the double standard and women’s conflicts between career and motherhood; her plays are still revived today. Unlike the other women in this study who are essentially “unknown,” Crothers has been extensively written about in dissertations and journals and, therefore, is not included in this study. For a recent arti- cle on Crothers, see Brenda Murphy, “Feminism and the Marketplace: The Career of Rachel Crothers,” in The Cambridge Companion to American Women Playwrights, ed. Brenda Murphy (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1999), 82–97. 5. About fifty-one women dramatists achieved two or more productions in New York between 1890 and 1920. Portions of this chapter are from Sherry Engle, “An ‘Irruption of Women Dramatists’: The Rise of America’s Woman Playwright, 1890–1920,” New England Theatre Journal 12 (2001): 27–50. 6. A prime example is Morton’s The Movers (1907), which despite being a box office failure, was defended by several prominent critics. -

AN ANALYSIS of the LIFE and LEGACY of LOUISA LANE DREW Rivka Kelly University of Vermont

University of Vermont ScholarWorks @ UVM UVM Honors College Senior Theses Undergraduate Theses 2014 THE DUCHESS: AN ANALYSIS OF THE LIFE AND LEGACY OF LOUISA LANE DREW Rivka Kelly University of Vermont Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/hcoltheses Recommended Citation Kelly, Rivka, "THE DUCHESS: AN ANALYSIS OF THE LIFE AND LEGACY OF LOUISA LANE DREW" (2014). UVM Honors College Senior Theses. 23. https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/hcoltheses/23 This Honors College Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Theses at ScholarWorks @ UVM. It has been accepted for inclusion in UVM Honors College Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ UVM. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE DUCHESS: AN ANALYSIS OF THE LIFE AND LEGACY OF LOUISA LANE DREW A Thesis Presented by Rivka Kelly to The Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of The University of Vermont In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the degree of Bachelor of Arts with Honors In Theatre May, 2014 Dedication This thesis is for my wonderful and supportive parents, whose gentle encouragement spurs me on yet reminds me that there are more important things in life than just a paper. Thanks Mom and Dad. And for the Students, Faculty and Staff who have strongly influenced my time here, helping (and sometimes forcing) me to grow personally and academically. I'm especially grateful to Natalie for her example and encouragement, and Avery for his help in the process, and to every single person who listened to me whine about this project. -

Movie Theaters in Washington State

United States Department of••the Interior National Park Service • .National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form This form is lor use in documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts." See instructions in Guidelines for Compfeting National Register Forms (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form lQ..90Q.a). Type all entries. A. Name of Multiple Property Listing Movie Theaters in Washington ·State from 1900 to 1948 B. Associated Historic Contexts Film Entertainment in Washington from 1900 to 1948 (Historic Contexts for future development) Stage, Musical, and Oratory Entertainment in Washington from Early Settlement to.19l5 Entertainment Entrepreneurs in Washington from 1850 to 1948 C. Geographical Data The State of Washington oSee continuation sheet D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act.ot 1966, as amended. I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the Nation Register documentation standards and setslorth requirements for the listing of related prop rties consistent with the N ional Registe; criteria. This submissio~ meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in Par and the Secreiary of the Interior's Standards for Planning and Evaluation. August 20, 1991 Date of Archaeology and Historic Preservation I, hereby, certify that this multiple property documentation form has been approved by the National Register as a basis for evaluating related properties for listing in the National Register. Signature 01 the Keeper 01 the National 'Heqister Date e__---'--e----- =E:-. -;.S'"'t-at:-e-m:-e:-n:':t-o--;t-;H"i'=s;:to::r7:,c:-";:;C:::o::n;:te::x:;t'" Discuss each historic context listed in Section B.