Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Carolingian, Romanesque, Gothic

3 periods: - Early Medieval (5th cent. - 1000) - Romanesque (11th-12th cent.) - Gothic (mid-12th-15th cent.) - Charlemagne’s model: Constantine's Christian empire (Renovatio Imperii) - Commission: Odo of Metz to construct a palace and chapel in Aachen, Germany - octagonal with a dome -arches and barrel vaults - influences? Odo of Metz, Palace Chapel of Charlemagne, circa 792-805, Aachen http://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=pwIKmKxu614 -Invention of the uniform Carolingian minuscule: revived the form of book production -- Return of the human figure to a central position: portraits of the evangelists as men rather than symbols –Classicism: represented as roman authors Gospel of Matthew, early 9th cent. 36.3 x 25 cm, Kunsthistorische Museum, Vienna Connoisseurship Saint Matthew, Ebbo Gospels, circa 816-835 illuminated manuscript 26 x 22.2 cm Epernay, France, Bibliotheque Municipale expressionism Romanesque art Architecture: elements of Romanesque arch.: the round arch; barrel vault; groin vault Pilgrimage and relics: new architecture for a different function of the church (Toulouse) Cloister Sculpture: revival of stone sculpture sculpted portals Santa Sabina, Compare and contrast: Early Saint-Sernin, Toulouse, Rome, 422-432 Christian vs. Romanesque France, ca. 1070-1120 Stone barrel-vault vs. timber-roofed ceiling massive piers vs. classical columns scarce light vs. abundance of windows volume vs. space size Saint-Sernin, Toulouse, Roman and Romanesque Architecture France, ca. 1070-1120 The word “Romanesque” (Roman-like) was applied in the 19th century to describe western European architecture between the 10th and the mid- 12th centuries Saint-Sernin, Toulouse, France, ca. 1070-1120 4 Features of Roman- like Architecture: 1. round arches 2. -

Laon Cathedral • Early Gothic Example with a Plan That Resembles Romanesque

Gothic Art • The Gothic period dates from the 12th and 13th century. • The term Gothic was a negative term first used by historians because it was believed that the barbaric Goths were responsible for the style of this period. Gothic Architecture The Gothic period began with the construction of the choir at St. Denis by the Abbot Suger. • Pointed arch allowed for added height. • Ribbed vaulting added skeletal structure and allowed for the use of larger stained glass windows. • The exterior walls are no longer so thick and massive. Terms: • Pointed Arches • Ribbed Vaulting • Flying Buttresses • Rose Windows Video - Birth of the Gothic: Abbot Suger and St. Denis Laon Cathedral • Early Gothic example with a plan that resembles Romanesque. • The interior goes from three to four levels. • The stone portals seem to jut forward from the façade. • Added stone pierced by arcades and arched and rose windows. • Filigree-like bell towers. Interior of Laon Cathedral, view facing east (begun c. 1190 CE). Exterior of Laon Cathedral, west facade (begun c. 1190 CE). Chartres Cathedral • Generally considered to be the first High Gothic church. • The three-part wall structure allowed for large clerestory and stained-glass windows. • New developments in the flying buttresses. • In the High Gothic period, there is a change from square to the new rectangular bay system. Khan Academy Video: Chartres West Facade of Chartres Cathedral, Chartres, France (begun 1134 CE, rebuilt after 1194 CE). Royal Portals of Chartres Cathedral, Chartres, France (begun 1134 CE, rebuilt after 1194 CE). Nave, Chartres Cathedral, Chartres, France (begun 1134 CE, rebuilt after 1194 CE). -

Contents Inhalt

34 Rome, Pantheon, c. 120 A.D. Contents 34 Rome, Temple of Minerva Medica, c. 300 A.D. 35 Rome, Calidarium, Thermae of Caracalla, 211-217 A.D. Inhalt 35 Trier (Germany), Porta Nigra, c. 300 A.D. 36 NTmes (France), Pont du Gard, c. 15 B.C. 37 Rome, Arch of Constantine, 315 A.D. (Plan and elevation 1:800, Elevation 1:200) 38-47 Early Christian Basilicas and Baptisteries Frühchristliche Basiliken und Baptisterien 8- 9 Introduction by Ogden Hannaford 40 Rome, Basilica of Constantine, 310-13 41 Rome, San Pietro (Old Cathedral), 324 42 Ravenna, Sant' Apollinare Nuovo, c. 430-526 10-19 Great Buildings of Egypt, Mesopotamia and Persia 42 Ravenna, Sant'Apollinare in Classe, 534-549 Grosse Bauten Ägyptens, Mesopotamiens und Persiens 43 Rome, Sant' Agnese Fuori Le Mura, 7th cent. 43 Rome, San Clemente, 1084-1108 12 Giza (Egypt), Site Plan (Scale 1:5000) 44 Rome, Santa Costanza, c. 350 13 Giza, Pyramid of Cheops, c. 2550 B.C. (1:800) 44 Rome, Baptistery of Constantine (Lateran), 430-440 14 Karnak (Egypt), Site Plan, 1550-942 B.C. (1:5000) 44 Nocera (Italy), Baptistery, 450 15 Abu-Simbel (Egypt), Great Temple of Ramesses II, c. 1250 B.C. 45 Ravenna, Orthodox Baptistery, c. 450 (1:800, 1:200) 15 Mycenae (Greece), Treasury of Atreus, c. 1350 B.C. 16 Medinet Habu (Egypt), Funerary Temple of Ramesses II, c. 1175 B.C. 17 Edfu (Egypt), Great Temple of Horus, 237-57 B.C. 46-53 Byzantine Central and Cross-domed Churches 18 Khorsabad (Iraq), Palace of Sargon, 721 B.C. -

FRANCE June 2019 As of 21Dec2018

FRANCE Reims, Le Puy, Paris Notre-Dame de Reims June 18 - 27, 2019 Join Cretin-Derham Hall Alumni on this once-in-a-lifetime Lasallian / Sisters of St. Joseph Pilgrimage Tour to France. We will “Walk in the Footsteps of our Founders - The Christian Brothers and The Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet”. Our trip will include overnight stays in Reims, Le Puy, and Paris along with visits to Liesse and Rouen. This fully escorted, all-inclusive, private tour will include the important historic sites associated with the life of St. Jean-Baptiste de La Salle and The Sisters of St. Joseph. *Sample Itinerary / Overnight City / Activities Tuesday, June 18: Depart Minneapolis for Paris (flight below) Wednesday, June 19: Reims - Arrive Paris! Transfer to Reims + Lunch + Visit to the Motherhouse of the Sisters of the Child Jesus + Visit Lasallian School Thursday, June 20: Reims - Guided tours to include: Founder’s House/The Hotel de La Cloche Museum + Reims Cathedral + College des Bons Enfants + St. Maurice + Basilica of St. Remi + Lunch + Time to Explore on your own Friday, June 21: Reims - Day Trip to Liesse / Option to walk 3 miles in to Liesse + Lunch + Visit burial site of Blessed Brother Arnold Reche returning to Reims Saturday, June 22: Le Puy - Depart Reims + Stop en route Dijon + Lunch at La Dame d’Aquitaine + Continue transfer to Le Puy + Hotel Check-in Sunday, June 23 Le Puy - Sisters of the Child Jesus Tour Monday, June 24: Paris - Depart Le Puy + stop en route Tuesday, June 25: Paris - Walking tour of Lasallian Paris - Visit St. -

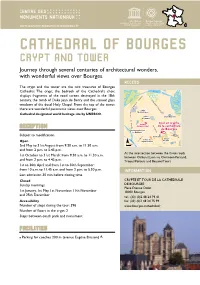

Crypt and Tower of Bourges Cathedral

www.tourisme.monuments-nationaux.fr CATHEDRAL OF BOURGES CRYPT AND TOWER Journey through several centuries of architectural wonders, with wonderful views over Bourges. ACCESS The crypt and the tower are the two treasures of Bourges Cathedral. The crypt, the bedrock of the Cathedral’s choir, displays fragments of the rood screen destroyed in the 18th century, the tomb of Duke Jean de Berry and the stained glass windows of the ducal Holy Chapel. From the top of the tower, there are wonderful panoramic views over Bourges. Cathedral designated world heritage site by UNESCO. RECEPTION Subject to modification. Open 2nd May to 31st August: from 9.30 a.m. to 11.30 a.m. and from 2 p.m. to 5.45 p.m. At the intersection between the three roads 1st October to 31st March: from 9.30 a.m. to 11.30 a.m. between Orléans/Lyon via Clermont-Ferrand, and from 2 p.m. to 4.45 p.m. Troyes/Poitiers and Beaune/Tours 1st to 30th April and from 1st to 30th September: from 10 a.m. to 11.45 a.m. and from 2 p.m. to 5.30 p.m. INFORMATION Last admission 30 min before closing time. Closed CRYPTE ET TOUR DE LA CATHÉDRALE Sunday mornings DE BOURGES Place Étienne Dolet 1st January, 1st May, 1st November, 11th November 18000 Bourges and 25th December tel.: (33) (0)2 48 24 79 41 Accessibility fax: (33) (0)2 48 24 75 99 Number of steps during the tour: 396 www.bourges-cathedrale.fr Number of floors in the crypt: 2 Steps between coach park and monument FACILITIES Parking for coaches 200 m (avenue Eugène Brisson) NORTH WESTERN FRANCE CENTRE-LOIRE VALLEY / CRYPT AND TOWER OF BOURGES -

ROBERT BORK School of Art and Art History, the University of Iowa Art

ROBERT BORK School of Art and Art History, The University of Iowa Art Building West, North Riverside Drive, Iowa City, IA 52242 Phone: 319-335-1762 E-mail: [email protected] EDUCATIONAL AND PROFESSIONAL HISTORY Education Princeton University. Ph.D., Architectural History, 1996; M.A. 1993. University of California, Santa Cruz. M.S., Physics, 1990. Passed qualifying exams for candidacy to Ph.D., 1991. Harvard University. B.A. CuM Laude, Physics, 1989. Granville High School, Granville, Ohio. Graduated Valedictorian, 1985. Professional and academic positions University of Iowa. Professor. Fall 1998 to Spring 2004 as Assistant Professor; promoted May 2004 to Associate Professor; promoted May 2012 to Full Professor. Florida Atlantic University. Assistant Professor. Fall 1997-Spring 1998. Sewanee, The University of the South. Visiting Assistant Professor. Fall 1996-Spring 1997. University of Connecticut. Visiting Lecturer. Fall 1995. Washington Cathedral. Technical Consultant. Periodic employment between 1993 and 1995. SCHOLARSHIP I: PUBLICATIONS Books (sole author) 1) Late Gothic Architecture: Its Evolution, Extinction, and Reception (Turnhout: Brepols, 2018), 562 pages. 2) The Geometry of Creation: Architectural Drawing and the Dynamics of Gothic Design (FarnhaM: Ashgate, 2011), 462 pages. The Geometry of Creation has been reviewed by Mailan Doquang in Speculum 87.3 (July, 2012), 842-844, by Stefan Bürger in Sehepunkte, www.sehepunkte.de/2012/07/20750.htMl, by Eric Fernie in The Burlington Magazine CLV, March 2013, 179-80, by David Yeomans in Construction History Society, Jan 2013, 23-25, by Paul Binski in Journal of the British Archaeological Association, 166, 2013, 212-14, by Paul Crossley in Architectural History, 56, 2013, 13-14, and by Michael Davis in JSAH 73, 1 (March, 2014), 169-171. -

Mont Saint-Michel, France

Mont Saint-Michel, France The beautiful Mont Saint-Michel at night The timeless treasure of Mont Saint-Michel rises from the sea like a fantasy castle. This small island, located off the coast in northern France, is attacked by the highest tides in Europe. Aubert, Bishop of Avranches, built the small church at the request of the Archangel Michael, chief of the ethereal militia. A small church was dedicated on October 16, 709. The Duke of Normandy requested a community of Benedictines to live on the rock in 966. It led to the construction of the pre-Romanesque church over the peak of the rock. The very first monastery buildings were established along the north wall of the church. The 12th century saw an extension of the buildings to the west and south. In the 14th century, the abbey was protected behind some military constructions, to escape the effects of the Hundred Years War. However, in the 15th century, the Romanesque church was substituted with the Gothic Flamboyant chancel. The medieval castle turned church has become one of the important tourist destinations of France. The township consists of several shops, restaurants, and small hotels. Travel Tips Remember that the tides here are very rough. Do not try to walk over sand as it is dangerous. Get the help of a guide if you wish to take a stroll over the tidal mudflats. The Mount has steep steps; climb carefully. Mont St-Michel Location Map Facts about Mont St-Michel The Mont St-Michel and its Bay were inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1979. -

Real Ideal Photography in France, 1847–1860

REAL IDEAL PHOTOGRAPHY IN FRANCE, 1847–1860 1. Henri Le Secq 2. Édouard Baldus French, 1818–1882 French, born Germany, 1813–1889 Small Dwelling in Mushroom Cave, 1851 Tour Saint-Jacques, Paris, 1852–1853 Salted paper print from a paper negative Salted paper print from a paper negative Image: 35.1 x 22.7 cm (13 13/16 x 8 15/16 in.) Image: 42.9 x 34 cm (16 7/8 x 13 3/8 in.) The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles 84.XP.370.24 84.XM.348.4 3. Henri Le Secq 4. Charles Nègre French, 1818–1882 French, 1820–1880 South Porch, Central Portal, Chartres Cathedral, 1852 Notre–Dame, Paris, about 1853 Waxed paper negative Waxed paper negative Image: 34 x 24 cm (13 3/8 x 9 7/16 in.) Image: 33.6 x 24 cm (13 1/4 x 9 7/16 in.) The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles 2015.39.1 2015.43.1 TRUST/horizontal.ai 6/8 point The J. Paul Getty Trust 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 403 Tel 310 440 7360 [email protected] Communications Department Los Angeles, CA 90049-1681 www.getty.edu 7/9 point The J. Paul Getty Trust 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 403 Tel 310 440 7360 [email protected] Communications Department Los Angeles, CA 90049-1681 www.getty.edu 8/10 point The J. Paul Getty Trust 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 403 Tel 310 440 7360 [email protected] Communications Department Los Angeles, CA 90049-1681 www.getty.edu 9/11 point The J. -

É an Installation by JR #Aupanth·On Ê

Press release, 25 February 2014 The CM N is inviting JR to create a participatory work at the Pantheon çTo the Pantheon!é an installation by JR #AuPanth·on ê www.au-pantheon.fr Press officer: Camille Boneu ê +33 (0)1 44 61 21 86 ê camille.boneu@ monuments-nationaux.fr çTo the Pantheon!é An installation by JR The restoration work currently being carried out on the Pantheon is one of the largest projects in Europe. The purpose of the current phase is to consolidate and fully restore the dome. A vast self-supporting scaffolding system ê a great technical feat ê has been built around the dome and will remain in place for two years. Last October the President of the Centre des Monuments Nationaux, Philippe Bélaval, presented the President of the French Republic with a report on the role of the Pantheon in promoting the values of the Republic. The title of this public report was “Pour faire entrer le peuple au Panthéon” (Getting people into the Pantheon), and it contains suggestions on how to make the monument more attractive, encourage French people to truly identify with it, and give it a greater role in Republican ceremonies. In order to give concrete form to these proposals, which have since been approved by the public authorities, the CMN has chosen to ask a contemporary artist to carry out a worldwide project embodying the values of this monument, which is so emblematic of the French Republic. Hence for the first tim e the worksite hoardings installed around a national m onum ent will be used to present a contem porary artistic venture instead of a lucrative advertising cam paign. -

University Micrcsilms International 300 N

INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this document, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark, it is an indication of either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, duplicate copy, or copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed. For blurred pages, a good image of the page can be found in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted, a target note will appear listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photographed, a definite method of “sectioning” the material has been followed. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand comer of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. -

Gothic Europe 12-15Th C

Gothic Europe 12-15th c. The term “Gothic” was popularized by the 16th c. artist and historian Giorgio Vasari who attributed the style to the Goths, Germanic invaders who had “destroyed” the classical civilization of the Roman empire. In it’s own day the Gothic style was simply called “modern art” or “The French style” Gothic Age: Historical Background • Widespread prosperity caused by warmer climate, technological advances such as the heavy plough, watermills and windmills, and population increase . • Development of cities. Although Europe remained rural, cities gained increasing prominence. They became centers of artistic patronage, fostering communal identity by public projects and ceremonies. • Guilds (professional associations) of scholars founded the first universities. A system of reasoned analysis known as scholasticism emerged from these universities, intent on reconciling Christian theology and Classical philosophy. • Age of cathedrals (Cathedral = a church that is the official seat of a bishop) • 11-13th c - The Crusades bring Islamic and Byzantine influences to Europe. • 14th c. - Black Death killing about one third of population in western Europe and devastating much of Europe’s economy. Europe About 1200 England and France were becoming strong nation-states while the Holy Roman Empire was weakened and ceased to be a significant power in the 13th c. French Gothic Architecture The Gothic style emerged in the Ile- de-France region (French royal domain around Paris) around 1140. It coincided with the emergence of the monarchy as a powerful centralizing force. Within 100 years, an estimate 2700 Gothic churches were built in the Ile-de-France alone. Abbot Suger, 1081-1151, French cleric and statesman, abbot of Saint- Denis from 1122, minister of kings Louis VI and Louis VII. -

The Cathedral of Bourges

Studies in Christian-Jewish Relations Volume 6 (2011): Jennings CP1-10 CONFERENCE PROCEEDING The Cathedral of Bourges: A Witness to Judeo-Christian Dialogue in Medieval Berry Margaret Jennings, Boston College Presented at the “Was there a „Golden Age‟ of Christian-Jewish Relations?” Conference at Boston College, April 2010 The term “Golden Age” appears in several contexts. In most venues, it both attracts and inspires controversy: Is the Golden Age, as technology claims, the year following a stunning break- through, now available for use? Is it, as moralists would aver, a better, purer time? Can it be identified, as social engineers would hope, as an epoch of heightened output in art, science, lit- erature, and philosophy? Does it portend, in assessing human development, an extended period of progress, prosperity, and cultural achievement? Factoring in Hesiod‟s and Ovid‟s understand- ing that a “Golden Age” was an era of great peace and happiness (Works and Days, 109-210 and Metamorphoses I, 89-150) is not particularly helpful because, as a mythological entity, their “golden age” was far removed from ordinary experience and their testimony is necessarily imag- inative. In the end, it is probably as difficult to define “Golden Age” as it is to speak of interactions between Jews and Christians in, what Jonathan Ray calls, “sweeping terms.” And yet, there were epochs when the unity, harmony, and fulfillment that are so hard to realize seemed almost within reach. An era giving prominence to these qualities seems to deserve the appellation “golden age.” Still, if religious differences characterize those involved, the possibility of disso- nance inevitably raises tension.