The Cathedral of Bourges

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

3. Orientations D'aménagement Et De Programmation

3. Orientations d’Aménagement et de Programmation Vu pour être joint à la délibération du Conseil Communautaire arrêtant le PLUI le 24 juin 2019 Annoix - Arçay - Berry-Bouy – Bourges - La Chapelle-Saint-Ursin - Le Subdray Lissay-Lochy – Marmagne – Morthomiers - Plaimpied-Givaudins - Saint-Doulchard Saint-Germain-du-Puy - Saint-Just - Saint-Michel-de-Volangis – Trouy - Vorly Projet de PLU-i Bourges Plus / Orientation d’Aménagement et de Programmation Projet de PLU-i Bourges Plus / Orientation d’Aménagement et de Programmation 3 Préambule Rôle des Orientations d’Aménagement et de Programmation Conformément à l’article L.151-6 du code de l’urbanisme en vigueur au 1er janvier 2016, le PLUi de Bourges PLUS comporte des Orientations d’Aménagement et de Programmation (OAP) établies en cohérence avec le Projet d’Aménagement et de Développement Durables (PADD) et portant sur des zones à Urbaniser ou des zones urbanisées. Conformément à l’article L.151-7, ces orientations peuvent notamment : ❖ Définir les actions et opérations nécessaires pour mettre en valeur l'environnement, notamment les continuités écologiques, les paysages, les entrées de villes et le patrimoine, lutter contre l'insalubrité, permettre le renouvellement urbain et assurer le développement de la commune ; ❖ Favoriser la mixité fonctionnelle en prévoyant qu'en cas de réalisation d'opérations d'Aménagement, de construction ou de réhabilitation un pourcentage de ces opérations est destiné à la réalisation de commerces ; ❖ Comporter un échéancier prévisionnel de l'ouverture à l'urbanisation des zones à urbaniser et de la réalisation des équipements correspondants ; ❖ Porter sur des quartiers ou des secteurs à mettre en valeur, réhabiliter, restructurer ou aménager ; ❖ Prendre la forme de schémas d’Aménagements et préciser les principales caractéristiques des voies et espaces publics ; ❖ Adapter la délimitation des périmètres, en fonction de la qualité de la desserte, où s'applique le plafonnement à proximité des transports. -

The Capital Sculpture of Wells Cathedral: Masons, Patrons and The

The Capital Sculpture of Wells Cathedral: Masons, Patrons and the Margins of English Gothic Architecture MATTHEW M. REEVE For Eric Fernie This paper considers the sculpted capitals in Wells cathedral. Although integral to the early Gothic fabric, they have hitherto eluded close examination as either a component of the building or as an important cycle of ecclesiastical imagery in their own right. Consideration of the archaeological evidence suggests that the capitals were introduced mid-way through the building campaigns and were likely the products of the cathedral’s masons rather than part of an original scheme for the cathedral as a whole. Possible sources for the images are considered. The distribution of the capitals in lay and clerical spaces of the cathedral leads to discussion of how the imagery might have been meaningful to diCerent audiences on either side of the choir screen. introduction THE capital sculpture of Wells Cathedral has the dubious honour of being one of the most frequently published but least studied image cycles in English medieval art. The capitals of the nave, transepts, and north porch of the early Gothic church are ornamented with a rich array of figural sculptures ranging from hybrid human-animals, dragons, and Old Testament prophets, to representations of the trades that inhabit stiC-leaf foliage, which were originally highlighted with paint (Figs 1, 2).1 The capitals sit upon a highly sophisticated pier design formed by a central cruciform support with triple shafts at each termination and in the angles, which oCered the possibility for a range of continuous and individual sculpted designs in the capitals above (Fig. -

Projet Aménagement Et Développement Durable

DÉPARTEMENT DU CHER COMMUNE DE SAINT GERMAIN DU PUY PLAN LOCAL D’URBANISME P.A.D.D. Projet d’Aménagement et de Développement Durable MODIFICATIONS : Jean-Pierre LOURS Urbaniste O.P.Q.U. Architecte D.P.L.G. D.E.A. analyse & Aménagement Membre de la S.F.A. 401-5 06 . 08 . 42 . 83 . 12 Eve PELLAT PAGÉ Juin 2010 Urbaniste Géographe Qualifiée O.P.Q.U. Formation A.E.U. REVISION PRESCRITE EN DATE DU 31 MARS 2009 C.E.A.A. Patrimoine PROJET DE P.L.U. ARRETE EN DATE DU 30 SEPTEMBRE 2010 Membre de la S.F.U. 06 . 12 . 70 . 05 . 23 APPROUVE EN DATE DU 29 SEPTEMBRE 2011 Yves MORLAND Architecte D.P.L.G. D.E.A. analyse & aménagement 06 . 08 . 41 . 33 . 25 ■ Bureau d’Etudes – Aménagement, Urbanisme, Architecture Tél.02.47.05.23.00 – Fax.02.47.05.23.01 – Site : www.be-aua.com S.A.R.L. B.E.-A.U.A., capital 8100 €, R.C.S. TOURS 439 030 958, N° ordre national S 04947 - régional S 1155, Courriel : [email protected] Siège : 69, rue Michel Colombe 37 000 TOURS – Agences : Bât 640 Zone aéroportuaire, 36 130 DEOLS et 1, rue Guillaume de Varye 18 000 BOURGES g r o u p e B.E.- A.U.A. / A T R I U M A r c h i t e c t u r e : e n s e m b l e, n o u s d e s s i n o n s v o t r e a v e n i r… Commune de SAINT-GERMAIN-DU-PUY Révision du Plan Local d’Urbanisme P.A.D.D. -

Horaire Ligne

Ho raires Ligne 110 A compter du 03 Septembre 2018 Cosne Cours-sur-Loire - Sancerre - Bourges Numéro de la course 110G 110H 110I 110J 110A 110B Période de circulation Scolaire Scolaire Scolaire Scolaire Année Année Jours de circulation LMMeJV LMMeJV LMMeJV LMMeJV LMMeJVS LMMeJVS COSNE COURS SUR LOIRE - SNCF (sur réservation) _ _ _ _ 7:20 12:40 SAINT SATUR - Fontenay 6:00 _ _ _ _ _ SAINT SATUR - Place de la République 6:05 _ _ _ 7:40 13:00 MENETREOL SOUS SANCERRE - Bourg 6:10 _ _ _ 7:43 13:03 SANCERRE - rue Nationale (les Remparts) _ _ _ _ 7:49 13:09 SANCERRE - Avenue de Verdun 6:16 _ _ _ 7:51 13:11 BUE - L'Esterille 6:22 _ _ _ 7:57 13:17 VEAUGUES - Place 6:33 _ _ _ _ _ MONTIGNY - Eglise 6:41 _ _ _ _ _ SAINT CEOLS - Eglise 6:46 _ _ _ 8:14 13:34 AZY - Haut Fouillet _ 6:20 _ _ _ _ ETRECHY - Le Nuainté _ 6:26 _ _ _ _ ETRECHY - Ecole _ 6:32 _ _ _ _ AZY - Eglise _ 6:37 _ _ _ _ RIANS - Jacques Cœur _ 6:46 _ _ _ _ RIANS - Les Granges _ 6:50 _ _ _ _ LES AIX D'ANGILLON - Route de Sancerre _ _ 6:40 _ _ _ LES AIX D'ANGILLON - Centre Culturel _ _ 6:43 _ 8:21 13:39 LES AIX D'ANGILLON - Place des Ormes _ _ 6:47 _ - _ SAINTE SOLANGE - Les Choux Verts _ _ _ 6:50 _ _ SAINTE SOLANGE - Moulin Neuf _ _ _ 6:52 _ _ SAINTE SOLANGE - Mairie _ _ _ 6:55 _ _ SAINTE SOLANGE - Les Forges _ _ _ 6:58 _ _ SAINT GERMAIN DU PUY - Lamartine _ _ _ _ 8:35 13:54 BOURGES - Hôpital _ _ _ _ 8:39 13:58 BOURGES - Pignoux _ _ _ _ 8:41 14:03 BOURGES - Condé Europe _ _ _ _ 8:45 14:07 BOURGES - Juranville _ _ _ _ 8:49 14:12 BOURGES - SNCF Quai C 7:20 7:19 7:13 7:12 8:54 14:14 BOURGES -

Contents Inhalt

34 Rome, Pantheon, c. 120 A.D. Contents 34 Rome, Temple of Minerva Medica, c. 300 A.D. 35 Rome, Calidarium, Thermae of Caracalla, 211-217 A.D. Inhalt 35 Trier (Germany), Porta Nigra, c. 300 A.D. 36 NTmes (France), Pont du Gard, c. 15 B.C. 37 Rome, Arch of Constantine, 315 A.D. (Plan and elevation 1:800, Elevation 1:200) 38-47 Early Christian Basilicas and Baptisteries Frühchristliche Basiliken und Baptisterien 8- 9 Introduction by Ogden Hannaford 40 Rome, Basilica of Constantine, 310-13 41 Rome, San Pietro (Old Cathedral), 324 42 Ravenna, Sant' Apollinare Nuovo, c. 430-526 10-19 Great Buildings of Egypt, Mesopotamia and Persia 42 Ravenna, Sant'Apollinare in Classe, 534-549 Grosse Bauten Ägyptens, Mesopotamiens und Persiens 43 Rome, Sant' Agnese Fuori Le Mura, 7th cent. 43 Rome, San Clemente, 1084-1108 12 Giza (Egypt), Site Plan (Scale 1:5000) 44 Rome, Santa Costanza, c. 350 13 Giza, Pyramid of Cheops, c. 2550 B.C. (1:800) 44 Rome, Baptistery of Constantine (Lateran), 430-440 14 Karnak (Egypt), Site Plan, 1550-942 B.C. (1:5000) 44 Nocera (Italy), Baptistery, 450 15 Abu-Simbel (Egypt), Great Temple of Ramesses II, c. 1250 B.C. 45 Ravenna, Orthodox Baptistery, c. 450 (1:800, 1:200) 15 Mycenae (Greece), Treasury of Atreus, c. 1350 B.C. 16 Medinet Habu (Egypt), Funerary Temple of Ramesses II, c. 1175 B.C. 17 Edfu (Egypt), Great Temple of Horus, 237-57 B.C. 46-53 Byzantine Central and Cross-domed Churches 18 Khorsabad (Iraq), Palace of Sargon, 721 B.C. -

Pages 114- 129 Great Architecture of the World Readings

Readings Pages 114- 129 Great Architecture of the World ARCH 1121 HISTORY OF ARCHITECTURAL TECHNOLOGY Photo: Alexander Aptekar © 2009 Gothic Architecture 1140-1500 Influenced by Romanesque Architecture While Romanesque remained solid and massive – Gothic: 1) opened up to walls with enormous windows and 2) replaced semicircular arch with the pointed arch. Style emerged in France Support: Piers and Flying Buttresses Décor: Sculpture and stained glass Effect: Soaring, vertical and skeleton-like Inspiration: Heavenly light Goal: To lift our everyday life up to the heavens Gothic Architecture 1140-1500 Dominant Art during this time was Architecture Growth of towns – more prosperous They wanted their own churches – Symbol of civic Pride More confident and optimistic Appreciation of Nature Church/Cathedral was the outlet for creativity Few people could read and write Clergy directed the operations of new churches- built by laymen Gothic Architecture 1140-1420 Began soon after the first Crusaders returned from Constantinople Brought new technology: Winches to hoist heavy stones New Translation of Euclid’s Elements – Geometry Gothic Architecture was the integration of Structure and Ornament – Interior Unity Elaborate Entrances covered with Sculpture and pronounced vertical emphasis, thin walls pierced by stained-glass Gothic Architecture Characteristics: Emphasis on verticality Skeletal Stone Structure Great Showing of Glass: Containers of light Sharply pointed Spires Clustered Columns Flying Buttresses Pointed Arches Ogive Shape Ribbed Vaults Inventive Sculpture Detail Sharply Pointed Spires Gothic Architecture 1140-1500 Abbot Suger had the vision that started Gothic Architecture Enlargement due to crowded churches, and larger windows Imagined the interior without partitions, flowing free Used of the Pointed Arch and Rib Vault St. -

Date Epoux Père Mère Ex

Date Epoux Père Mère Ex.conjoint Origine __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ 14/11/1877 ADAM Alix François Aignan Désir DESPREAUX Françoise MAREUIL JUSSERAND Henri Philippe Philippe PINOTEAU Marie Joséph CHOUDAY 11/02/1738 ALIN Marie Justin BEAUSSIER Jeanne ST AMBROIX PINOTEAU Georges Jean +FEUILLET Marie CONDÉ 03/02/1864 AMYOT Blaise Etienne +FERRAGU Marie ST AMBROIX GIMONET Anne +André ORVELIN Marie CHOUDAY 23/01/1755 ANGELIER Françoise +Barthélémy +RONDET Catherine CHOUDAY LAFORET Gabriel +MERY Marie ST AMBROIX 29/11/1814 ARNOUX Philippe +Pierre GUIBOURET Solange LIZERAY CHAMARD Catherine Pierre BLONDEAU Jeanne CHOUDAY 10/02/1787 ARNOUX Pierre +Jean FIGNON Catherine NOTZ CHAMARD Françoise +Charles AUFRERE Madeleine CHOUDAY 18/06/1832 AUBRU Anne +Gilbert +GOURIAT Marguerite MAREUIL PERICARD Jacques Joseph SALOMON Marie +LERASLE Jacques CIVRAY 30/12/1839 AUBRUN Elisabeth +Gilbert +GAURIAT Marguerite DAMPIERRE PERICARD Pierre Joseph +SALOMON Marie CHOUDAY 01/02/1836 AUBRUN Marguerite +Gilbert +GAURIAT Marguerite MAREUIL PERICARD Jacques Joseph SALOMON Marie CHOUDAY 02/07/1811 AUBRUN Martin +Silvain +RAFIN Marie ST AOUT CHUAT Brigitte Etienne COMPAIN Brigitte ISSOUDUN ST CYR 25/02/1805 AUCLERC Pierre +Silvain +GORJON Jeanne FEUSINES FAVEREAU Anne Jacques +BAUDIN Marie CHOUDAY 09/02/1836 AUCLERC Pierre +Silvain +GORJON Jeanne +FAVEREAU Anne FEUSINES GAILLARD Madeleine +Paul +FONTAINE Anne +LOUIS Denis CHOUDAY 16/11/1773 AUFIEVRE Charles +François -

1.4 (Lyon) NEVERS BOURGES VIERZON ORLÉANS HORAIRES VALABLES DU 31 AOÛT AU 12 DÉCEMBRE 2020

1.4 (Lyon) NEVERS BOURGES VIERZON ORLÉANS HORAIRES VALABLES DU 31 AOÛT AU 12 DÉCEMBRE 2020 Les horaires de cette fiche sont com- RÉMI RÉMI Transporteur RÉMI RÉMI RÉMI RÉMI RÉMI RÉMI EXPRESS RÉMI RÉMI RÉMI RÉMI RÉMI RÉMI RÉMI RÉMI EXPRESS RÉMI RÉMI RÉMI RÉMI RÉMI INTERCITÉS RÉMI RÉMI RÉMI RÉMI RÉMI RÉMI RÉMI muniqués à titre indicatif (document 860820 861340 861342 860851 861302 860853 3904 861420 861552 861383 861422 861430 861554 861387 861556 3908 861404 860860 861560 860830 861428 4504 861562 861391 860834 861566 16848 861568 861322 non contractuel) ; ils sont établis à la date Numéro de circulation d’impression et susceptibles d’évoluer au Lun Lun Lun Lun Lun Lun Lun Lun Lun Lun Mar Lun Lun Lun Lun Lun Lun Lun Lun Lun Lun Lun Lun Lun Ven Lun Lun Lun Lun cours de la période d’application. à à à à à à à à à à à à à à à à à à à à à à à à à à Jours de circulation Ven Ven Ven Ven Ven Ven Ven Ven Ven Ven Ven Ven Ven Ven Ven Ven Ven Ven Ven Ven Ven Ven Ven Ven Ven Ven Nous vous invitons à consulter les services d’information à votre disposition avant d’en- Renvois treprendre votre voyage, en particulier lors LYON-PERRACHE 09.22 11.43 des veilles et lendemains de fêtes, jours fériés LYON-PART-DIEU 09.34 11.57 et vacances scolaires. NEVERS 05.09 06.09 06.45 07.45 09.36 12.18 12.45 15.21 La Guerche-sur-l’Aubois 06.58 07.58 12.58 Nérondes 07.06 08.06 13.06 Horaires, arrêts et parcours susceptibles Bengy 07.11 08.11 13.11 d’être modifiés en raison de travaux ou Avord 05.36 07.17 08.17 13.17 St-Germain-du-Puy 07.27 08.27 13.27 adaptés pendant les vacances scolaires. -

Livret D'accueil 2020

GUIDE DE PLAIMPIED-GIVAUDINS 2020 - 2021 LE MOT DU MAIRE Madame, Monsieur Plaimpied-Givaudins, née de la fusion des communes de Plaimpied et Givaudins en 1842, a connu une forte expansion depuis un demi-siècle, sa population passant de 700 à 2000 habitants. Pour autant, elle conserve l’authenticité d’un village au riche patrimoine historique avec l’abbaye de Plaimpied dont il nous reste une magnifique abbatiale romane, des bâtiments remarquables occupés aujourd’hui par la mairie et un immense parc. Plaimpied-Givaudins présente un vaste territoire de plus de 4 000 hectares traversé par la rivière l’Auron et le canal de Berry (longé d’une piste cyclable depuis 2019), avec au nord le lac d’Auron et l’espace naturel sensible du bas marais alcalin. L’attractivité de Plaimpied-Givaudins repose sur la présence de tous les commerces et services de proximité nécessaires ainsi que la richesse et la diversité de la vie associative proposant un choix très large d’activités culturelles ou sportives s’adressant à tous les âges. Pour répondre encore mieux aux attentes des habitants, la commune conduit un effort d’investissement important pour disposer d’équipements publics de qualité dans tous les domaines. Madame, Monsieur, vous êtes les bienvenus à Plaimpied-Givaudins et je vous souhaite d’y trouver la sérénité et la joie de vivre. Votre Maire, Patrick BARNIER 2 SOMMAIRE Plaimpied-Givaudins Développement durable Histoire et patrimoine ▪ Présentation 5 ▪ Collecte des ordures ménagères 31 ▪ Plan de la commune 6 ▪ Dépôt en déchetterie 31 ▪ Du Moyen-âge -

China Gothic: Indigenous' Church Design in Late- Imperial Beijing Anthony E

Whitworth Digital Commons Whitworth University History Faculty Scholarship History 2015 China Gothic: Indigenous' Church Design in Late- Imperial Beijing Anthony E. Clark Whitworth University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.whitworth.edu/historyfaculty Part of the Architectural History and Criticism Commons, Asian Art and Architecture Commons, Asian History Commons, and the History of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Clark, Anthony E. , "China Gothic: Indigenous' Church Design in Late-Imperial Beijing" Whitworth University (2015). History Faculty Scholarship. Paper 10. http://digitalcommons.whitworth.edu/historyfaculty/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History at Whitworth University. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Whitworth University. SAH ANNUAL CONFERENCE IN CHICAGO, 2015 Presentation Paper Panel: “The Invaluable Indegine: Local Expertise in the Imperial Context” Paper Title: “China Gothic: ‘Indigenous’ Church Design in Late-Imperial Beijing” Presenter: Anthony E. Clark, Associate Professor of Chinese History (Whitworth University) Abstract: In 1887 the French ecclesiastic-cum-architect, Bishop Alphonse Favier, negotiated the construction of Beijing’s most extravagant church, the North Church cathedral, located near the Forbidden City. China was then under a semi-colonial occupation of missionaries and diplomats, and Favier was an icon of France’s mission civilisatrice. For missionaries such as Favier, Gothic church design represented the inherent caractère Français expected to “civilize” the Chinese empire. Having secured funds from the imperial court to build his ambitious Gothic cathedral, the French bishop enlisted local builders to realize his architectural vision, which consisted of Gothic arches, exaggerated finials, and a rose widow with delicate tracery above the front portal. -

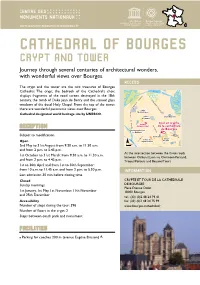

Crypt and Tower of Bourges Cathedral

www.tourisme.monuments-nationaux.fr CATHEDRAL OF BOURGES CRYPT AND TOWER Journey through several centuries of architectural wonders, with wonderful views over Bourges. ACCESS The crypt and the tower are the two treasures of Bourges Cathedral. The crypt, the bedrock of the Cathedral’s choir, displays fragments of the rood screen destroyed in the 18th century, the tomb of Duke Jean de Berry and the stained glass windows of the ducal Holy Chapel. From the top of the tower, there are wonderful panoramic views over Bourges. Cathedral designated world heritage site by UNESCO. RECEPTION Subject to modification. Open 2nd May to 31st August: from 9.30 a.m. to 11.30 a.m. and from 2 p.m. to 5.45 p.m. At the intersection between the three roads 1st October to 31st March: from 9.30 a.m. to 11.30 a.m. between Orléans/Lyon via Clermont-Ferrand, and from 2 p.m. to 4.45 p.m. Troyes/Poitiers and Beaune/Tours 1st to 30th April and from 1st to 30th September: from 10 a.m. to 11.45 a.m. and from 2 p.m. to 5.30 p.m. INFORMATION Last admission 30 min before closing time. Closed CRYPTE ET TOUR DE LA CATHÉDRALE Sunday mornings DE BOURGES Place Étienne Dolet 1st January, 1st May, 1st November, 11th November 18000 Bourges and 25th December tel.: (33) (0)2 48 24 79 41 Accessibility fax: (33) (0)2 48 24 75 99 Number of steps during the tour: 396 www.bourges-cathedrale.fr Number of floors in the crypt: 2 Steps between coach park and monument FACILITIES Parking for coaches 200 m (avenue Eugène Brisson) NORTH WESTERN FRANCE CENTRE-LOIRE VALLEY / CRYPT AND TOWER OF BOURGES -

ROBERT BORK School of Art and Art History, the University of Iowa Art

ROBERT BORK School of Art and Art History, The University of Iowa Art Building West, North Riverside Drive, Iowa City, IA 52242 Phone: 319-335-1762 E-mail: [email protected] EDUCATIONAL AND PROFESSIONAL HISTORY Education Princeton University. Ph.D., Architectural History, 1996; M.A. 1993. University of California, Santa Cruz. M.S., Physics, 1990. Passed qualifying exams for candidacy to Ph.D., 1991. Harvard University. B.A. CuM Laude, Physics, 1989. Granville High School, Granville, Ohio. Graduated Valedictorian, 1985. Professional and academic positions University of Iowa. Professor. Fall 1998 to Spring 2004 as Assistant Professor; promoted May 2004 to Associate Professor; promoted May 2012 to Full Professor. Florida Atlantic University. Assistant Professor. Fall 1997-Spring 1998. Sewanee, The University of the South. Visiting Assistant Professor. Fall 1996-Spring 1997. University of Connecticut. Visiting Lecturer. Fall 1995. Washington Cathedral. Technical Consultant. Periodic employment between 1993 and 1995. SCHOLARSHIP I: PUBLICATIONS Books (sole author) 1) Late Gothic Architecture: Its Evolution, Extinction, and Reception (Turnhout: Brepols, 2018), 562 pages. 2) The Geometry of Creation: Architectural Drawing and the Dynamics of Gothic Design (FarnhaM: Ashgate, 2011), 462 pages. The Geometry of Creation has been reviewed by Mailan Doquang in Speculum 87.3 (July, 2012), 842-844, by Stefan Bürger in Sehepunkte, www.sehepunkte.de/2012/07/20750.htMl, by Eric Fernie in The Burlington Magazine CLV, March 2013, 179-80, by David Yeomans in Construction History Society, Jan 2013, 23-25, by Paul Binski in Journal of the British Archaeological Association, 166, 2013, 212-14, by Paul Crossley in Architectural History, 56, 2013, 13-14, and by Michael Davis in JSAH 73, 1 (March, 2014), 169-171.