Evaluation of the Performance of Station Wear Worn Under a NFPA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evaluating the Results of a Modified Bunker Gear Policy

Format changes have been made to facilitate reproduction. While these research projects have been selected as outstanding, other NFA EFOP and APA format, style, and procedural issues may exist. EVALUATING THE RESULTS OF A MODIFIED BUNKER GEAR POLICY EXECUTIVE DEVELOPMENT BY: David Mager Boston Fire Department Boston, Massachusetts An applied research project submitted to the National Fire Academy as part of the Executive Fire Officer Program September 2002 - 1 - Format changes have been made to facilitate reproduction. While these research projects have been selected as outstanding, other NFA EFOP and APA format, style, and procedural issues may exist. - 2 - Format changes have been made to facilitate reproduction. While these research projects have been selected as outstanding, other NFA EFOP and APA format, style, and procedural issues may exist. ABSTRACT In August 2000, Boston Fire Department (BFD) modified its mandatory bunker gear policy to permit less than full bunker gear. The problem was that no evaluation of the policy change was performed to determine whether or not firefighter safety was enhanced. The purpose of this research was to determine if modifying the BFD bunker gear policy enhanced firefighter safety. An historical and evaluative research methodology was used to answer the following questions: 1. Prior to the modification of the bunker gear policy, what was the injury rate for heat stress injuries on the fireground? 2. Did the rate of heat stress injuries go down after the modification of the policy? 3. Did any other category of injuries increase after the policy change? 4. What must BFD do to ensure optimum safety for its firefighters? The procedures involved an examination of injury statistics before and after the change. -

Bunker Gear for Fire Fighters: Does It Fit Today’S Fire Fighters?

Volume 9, Issue 3, 2015 Bunker Gear for Fire Fighters: Does it fit today’s fire fighters? Lynn M. Boorady, Associate Professor and Chair, Fashion and Textile Technology Department, State University of New York - Buffalo State ABSTRACT The fit of bunker gear is important to ensure the protection of the firefighter when they are combating structural fire and performing other hazardous duties. Bunker gear is regulated by the National Fire Protection Agency (NFPA) which requires a range of sizes and certain fit regulations due to safety. Firefighters are a specific segment of the population which may be appropriate for a specific sizing scheme. Body scans of career and volunteer male firefighters were compared to SizeUSA data. Differences were found in the height and weight, with male firefighters being heavier and taller than the general population. This research also looks at the procurement and sizing of bunker gear, analyzes body scan data specific to the firefighter population and suggests developing a sizing system specific to this population. A larger study would need to be conducted in order obtain statistically significant results. Keywords: Bunker gear, Firefighter protection, Turnout gear Introduction is needed in order to create a sizing scheme The image of the heroic fire fighter is for this target market. iconic. Firefighting is considered a According to the U.S. Fire prestigious occupation by 97% of the Administration, in 2013 there were 1,140,750 American public, according to a 2006 Harris fire fighters in the United States. Of those, Poll. Fire fighters walk into fire engulfed 354,600 were professional (or “career”) and buildings to save lives, put themselves in 786,150 were volunteers (U. -

ROWLETT, TEXAS FIRE RESCUE Entry Level Applicant JOB TASK SIMULATION TEST ADMINISTRATION GUIDE

ROWLETT, TEXAS FIRE RESCUE Entry Level Applicant JOB TASK SIMULATION TEST ADMINISTRATION GUIDE Stanard & Associates, Inc. June 2007 Revised June 2010 INTRODUCTION A content-oriented strategy was used to develop a valid job task simulation examination designed to measure the basic physical skills necessary for successful performance as a Rowlett Fire Rescue firefighter. The entire examination is composed of job-related physical skills. Only those skills that do not require training to become proficient are assessed. This means the exam is equally valid for assessing the physical skills of individuals who have had fire experience and those who have not. The test sequence outlined herein is used by Rowlett Fire Rescue for entry-level selection. A meeting with subject matter experts at Rowlett Fire Rescue, along with an analysis of data collected from current Rowlett firefighting personnel on a comprehensive fire services job analysis questionnaire provided the background knowledge necessary to develop this job-related physical ability examination. Recommended modifications were made June 2010. Recommendations were made by the JTS committee, a panel of Firefighters, Drivers and Officers of Rowlett Fire Rescue. This manual includes all specifications and instructions necessary to administer the job task simulation to entry-level applicants. It begins with a list of what test takers must wear and all materials necessary to conduct the test. Then, the duties of the lead administrator and proctors are detailed. Next, testing assumptions are listed. The timed sequence of events is described and each component is briefly discussed. The untimed event is also described and administration instructions are provided. Important course measurements are then provided. -

Engine Riding Positions Officer Heo Nozzle Ff

MILWAUKEE FIRE DEPARTMENT Operational Guidelines Approved by: Chief Mark Rohlfing 2012 FORWARD The purpose of these operational guidelines is to make clear expectations for company performance, safety, and efficiency, eliminating the potential for confusion and duplication of effort at the emergency scene. It is understood that extraordinary situations may dictate a deviation from these guidelines. Deviation can only be authorized by the officer/acting officer of an apparatus or the incident commander. Any deviation must be communicated over the incident talk group. The following guidelines are meant to clarify best operational practices for the MFD. They are not intended to be all-inclusive and are designed to be updated as necessary. They are guidelines for you to use. However, there will be no compromise on issues of safety, chain of command, correct gear usage, or turnout times (per NFPA 1710). These operating guidelines will outline tool and task responsibilities for the specific riding positions on responding units. While the title of each riding position and the assignments that follow may not always seem to be a perfect pairing, the tactical advantage of knowing where each member is supposed to be operating at a given assignment will provide for increased accountability and increased effectiveness while performing our response duties. Within the guidelines, you will see run-type specific (and in some cases, arrival order specific) tool and task assignments. On those responses listing a ‘T (or R)’ as the response unit, the Company will be uniformly listed as ‘Truck’ for continuity. The riding positions are as follows: ENGINE RIDING POSITIONS OFFICER HEO NOZZLE FF BACKUP FF TRUCK RIDING POSITIONS OFFICER HEO VENT FF FORCE FF SAFETY If you see something that you believe impacts our safety, it is your duty to report it to your superior Officer immediately. -

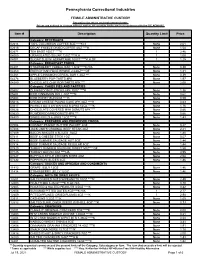

FEMALE ADMINISTRATIVE CUSTODY See Policy for Return and Replacement Terms

Pennsylvania Correctional Industries FEMALE ADMINISTRATIVE CUSTODY See policy for return and replacement terms. Prices are subject to change without notice. All quantity limits are in accordance with the DC ADM-815. Item # Description Quantity Limit Price Category: BEVERAGES 02614 100% COLUMBIAN COFFEE 5OZ ****K,H None 2.61 02616 DECAF FREEZE DRIED COFFEE 4OZ ****K None 1.54 02671 TEA BAGS 100CT ****K 1 2.46 04000 GRANULATED SUGAR 12OZ ****K,H 1 1.00 04001 SUGAR SUB W/ ASPARTAME 100CT ****K,H,GF 1 1.25 Category: BREAKFAST FOODS 04201 STRAWBERRY CEREAL BAR 1.3OZ ****K,H/A None 0.39 04260 ENERGY BAR,FDGE BRWNE 2.64OZ****GF None 1.31 04261 APPLE CINNAMON CEREAL BAR 1.3OZ *** None 0.39 04276 BLUEBERRY POP-TARTS 8PK None 1.97 04280 CHOCOLATE CHIP POP-TARTS 8PK *** None 2.00 Category: CAKES PIES AND PASTRIES 05602 DUNKIN DONUT STICKS 6PK 10OZ ****K None 1.36 05604 ICED CINNAMON ROLL 4OZ ****K None 0.62 05608 ICED HONEY BUN 6OZ ****K None 0.59 05616 CREAM CHEESE POUND CAKE 2PK 4OZ ****K None 0.63 05617 PEANUT BUTTER WAFERS 6-2PKS 12OZ ****K None 1.76 05628 CHOCOLATE COVERED MINI DONUTS 6PK *** None 0.66 05630 POWDERED MINI DONUTS 6PK *** None 0.66 06800 SWISS ROLLS 6-2PKS 12OZ ****K None 1.43 Category: PREPARED AND PRESERVED FOODS 07004 CREAMY PEANUT BUTTER PACKET 2OZ None 0.27 07406 JACK LINK'S ORIGINAL BEEF STEAK 2OZ None 2.21 07409 BACON SINGLES 6 SLICES .78OZ None 1.80 07411 BEEF & CHEESE STICK 1OZ None 0.57 07413 BEEF SUMMER SAUSAGE HOT 5OZ None 1.44 07414 BEEF SUMMER SAUSAGE REGULAR 5OZ None 1.44 07420 TURKEY SUMMER SAUSAGE SWEET 5OZ****GF -

Boxers Or Briefs Poll

Boxers Or Briefs Poll Fun Poll, Boxers or Briefs? Cast your vote and then share with your friends to get their vote. Welcome to Zity. 15%: Plain nondescript underwear. I personally prefer boxers, but they get so annoying. For women the options were briefs, bikini, shorts and thongs. Pants for sport, boxers otherwise. Seems it's a big deal with some of the younger crowd out there, (under 40) that says it's a big deal if you wear whitey tightys, boxers of briefs. 57% (647) Boxer briefs. Sam Talbot (Top Chef) - "boxers, briefs and commando" Rob Thomas (lead singer of Matchbox Twenty) Justin Timberlake (pop musician and actor) - started in briefs; switched to boxers; then to boxer briefs and sometimes commando; about boxer briefs, his current preference, he says: "like the way they hold everything together". 10 Answers. The new findings from the National Poll on Healthy Aging suggest that more physicians should routinely ask their older female patients about incontinence issues they might be experiencing. Tighty Whiteys are NOT cool (not saying you show your underwear to everyone). Share Followers 0. They also offer refastenable hook tabs and curved leg elastics like adult diapers for a fit that stays in place and helps you, or those you love, stay confident and comfortable. This comment has been removed by the author. Here's how to debrief his briefs. Kagura = 878 8. Boxers, Briefs and Battles. I in uncomplicated words switched to briefs/boxers, which ability i have were given lengthy lengthy previous from in uncomplicated words boxers to many times situations boxers, on get jointly briefs. -

HANESBRANDS INC GOING COMMANDO September 13, 2016 DISCLAIMER

BRIAN MCGOUGH ALEC RICHARDS JEREMY MCLEAN HANESBRANDS INC GOING COMMANDO September 13, 2016 DISCLAIMER DISCLAIMER Hedgeye Risk Management is a registered investment advisor, registered with the State of Connecticut. Hedgeye Risk Management is not a broker dealer and does not provide investment advice for individuals. This research does not constitute an offer to sell, or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. This research is presented without regard to individual investment preferences or risk parameters; it is general information and does not constitute specific investment advice. This presentation is based on information from sources believed to be reliable. Hedgeye Risk Management is not responsible for errors, inaccuracies or omissions of information. The opinions and conclusions contained in this report are those of Hedgeye Risk Management, and are intended solely for the use of Hedgeye Risk Management’s clients and subscribers. In reaching these opinions and conclusions, Hedgeye Risk Management and its employees have relied upon research conducted by Hedgeye Risk Management’s employees, which is based upon sources considered credible and reliable within the industry. Hedgeye Risk Management is not responsible for the validity or authenticity of the information upon which it has relied. TERMS OF USE This report is intended solely for the use of its recipient. Re-distribution or republication of this report and its contents are prohibited. For more details please refer to the appropriate sections of the Hedgeye Services Agreement and the Terms of Use at www.hedgeye.com © Hedgeye Risk Management LLC, All Rights Reserved. 2 PLEASE SUBMIT QUESTIONS* TO [email protected] *ANSWERED AT THE END OF THE CALL STILL CALLING IT LIKE WE SEE IT 1) Core business weakening. -

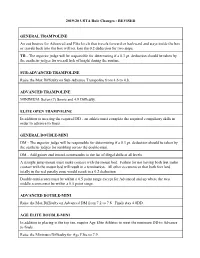

2019-20 USTA Rule Changes - REVISED

2019-20 USTA Rule Changes - REVISED GENERAL TRAMPOLINE An out bounce for Advanced and Elite levels that travels forward or backward and stays inside the box or travels back into the box will not lose the 0.2 deduction for two steps. TR - The superior judge will be responsible for determining if a 0.3 pt. deduction should be taken by the aesthetic judges for overall lack of height during the routine. SUB-ADVANCED TRAMPOLINE Raise the Max Difficulty on Sub-Advance Trampoline from 4.6 to 4.8. ADVANCED TRAMPOLINE MINIMUM: Seven (7) Somis and 4.9 Difficulty. ELITE OPEN TRAMPOLINE In addition to meeting the required DD - an athlete must complete the required compulsory skills in order to advance to finals. GENERAL DOUBLE-MINI DM - The superior judge will be responsible for determining if a 0.3 pt. deduction should be taken by the aesthetic judges for tumbling across the double-mini. DM - Add gainer and inward somersaults to the list of illegal skills at all levels. A straight jump mount must make contact with the mount bed. Failure for not having both feet make contact with the mount bed will result in a termination. All other occurrences that both feet land totally in the red penalty zone would result in a 0.2 deduction. Double-mini scores must be within a 0.5 point range except for Advanced and up where the two middle scores must be within a 0.5 point range. ADVANCED DOUBLE-MINI Raise the Max Difficulty on Advanced DM from 7.2 to 7.8 Finals stay 4.8DD. -

Replace Bunker Gear STRATEGIC PLAN GOAL: Organizational Excellence PROJECT STATUS: Unfunded - Mandatory Replacement START/FINISH DATE: Jul-16 Dec-16

TETON COUNTY, WYOMING FY 2017-2021 CAPITAL IMPROVEMENT PLAN DEPARTMENT: Fire Department PROJECT TITLE: Replace Bunker Gear STRATEGIC PLAN GOAL: Organizational Excellence PROJECT STATUS: Unfunded - mandatory replacement START/FINISH DATE: Jul-16 Dec-16 PROJECT MANAGER: BC Redwine DEPARTMENT PRIORITY: High Note: Be sure to complete Project Cost Spreadsheets associated with the project request. In addition, include any other graphics that describe the project (i.e. site plan, map, etc.) Project Description: Replace Dated Bunker Gear per NFPA standard every 10 years. Bunker gear is used to protect firefighters when entering dangerous environments. This includes a jacket and pants. Nomex hood, leather insulated gloves, a helmet and rubber boots complete the ensemble but are not included in this project. The jacket and pants are insulated for heat protection and have other safety qualities built in. Project Justification: National Fire Protection Agency ( NFPA)(similar to OSHA or NIOSH) sets goals and standards for firefighting and firefighters. One of the basic standards is to replace bunker gear every ten years. More recent research on carcinogens points to even more frequent replacement but has not made that assertion to date. Fire/EMS has 100-110 firefighters county wide including all job types from volunteer to Chief. Rotating the oldest stock is the best way to keep the oldest gear out of Immediately Dangerous to Life & Health (IDLH) incidents and situations. Method for Estimating Cost: Requested pricing from several vendors Project Status -

Clothing Terms from Around the World

Clothing terms from around the world A Afghan a blanket or shawl of coloured wool knitted or crocheted in strips or squares. Aglet or aiglet is the little plastic or metal cladding on the end of shoelaces that keeps the twine from unravelling. The word comes from the Latin word acus which means needle. In times past, aglets were usually made of metal though some were glass or stone. aiguillette aglet; specifically, a shoulder cord worn by designated military aides. A-line skirt a skirt with panels fitted at the waist and flaring out into a triangular shape. This skirt suits most body types. amice amice a liturgical vestment made of an oblong piece of cloth usually of white linen and worn about the neck and shoulders and partly under the alb. (By the way, if you do not know what an "alb" is, you can find it in this glossary...) alb a full-length white linen ecclesiastical vestment with long sleeves that is gathered at the waist with a cincture aloha shirt Hawaiian shirt angrakha a long robe with an asymmetrical opening in the chest area reaching down to the knees worn by males in India anklet a short sock reaching slightly above the ankle anorak parka anorak apron apron a garment of cloth, plastic, or leather tied around the waist and used to protect clothing or adorn a costume arctic a rubber overshoe reaching to the ankle or above armband a band usually worn around the upper part of a sleeve for identification or in mourning armlet a band, as of cloth or metal, worn around the upper arm armour defensive covering for the body, generally made of metal, used in combat. -

Essentials of Fire Fighting, 6Th Edition

ESSENTIALS OF FIRE FIGHTING INTERNATIONAL FIRE SERVICE TRAINING ASSOCIATION Firefighter Personal Protective Equipment Chapter Contents Case History ......................................259 Donning from a Side or Rear Personal Protective Equipment ...............259 External Mount .......................................... 300 Donning from a Backup Mount...................... 300 Structural Fire Fighting Protective Clothing .. 261 Donning the Facepiece .................................. 301 Wildland Personal Protective Clothing .......... 270 Doffing Protective Breathing Apparatus ....... 302 Roadway Operations Clothing ....................... 273 Emergency Medical Protective Clothing ........274 Inspection and Maintenance of Protective Special Protective Clothing ............................274 Breathing Apparatus ......................303 Station/Work Uniforms ................................. 276 Protective Breathing Apparatus Inspections and Care ..................................................... 303 Care of Personal Protective Clothing ............ 277 Annual Inspection and Maintenance ............. 306 Safety Considerations for Personal Protective Equipment ............................... 280 SCBA Air Cylinder Hydrostatic Testing .......... 306 Respiratory Protection ..........................281 Refilling SCBA Cylinders ............................... 307 Respiratory Hazards ...................................... 281 Replacing SCBA Cylinders ..............................311 Types of Respiratory Using Respiratory Protection Equipment -

Whereas, the Commission of the City of Sanford, Florida Has Adopted an Annual Operating Budget for the Fiscal Year Beginning October 1, 2020 and Terminating On

Resolution No. 2941 A Resolution of the City of Sanford, Florida, amending the City's annual operating budget for the fiscal year beginning October 1, 2020 and ending September 30, 2021; providing for implementing administrative actions; providing for a savings provision; providing for conflicts; providing for severability and providing for an effective date. Whereas, the Commission of the City of Sanford, Florida has adopted an annual operating budget for the fiscal year beginning October 1, 2020 and terminating on September 30, 2021 specifying certain projected revenues and expenditures for the operations of Sanford municipal government; and Whereas, the City's budget presumes that each department generally will, to the best of their ability, maintain its expenditures within its allocated budgeted level and exercise prudence in expending funds during the course of the City's fiscal year; and Whereas, from time-to-time circumstances and events may require that the original City budget may need revision; and Whereas, the City Commission, in its judgment and discretion, has the authority to adjust the budget to more closely coincide with actual and expected events. Now, therefore, be it adopted and resolved by the City Commission of the City of Sanford, Florida as follows: Section 1. Adoption of Budget Amendment. The annual operating budget of the City of Sanford for the fiscal year beginning October 1, 2020 and terminating on September 30, 2021 is hereby revised and amended by Attachment "A". The Attachment is hereby incorporated into this Resolution as if fully set forth herein verbatim. Except as amended herein, the annual operating budget for the City of Sanford for fiscal year beginning October 1, 2020 and terminating on September 30, 2021 shall remain in full force and effect.