The Lone Ranger from the East: Towards 1900

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Suspension Bridge Corner, Seventh and Main Streets 3 I-- ' O LL G OREGON CITY, OREGON

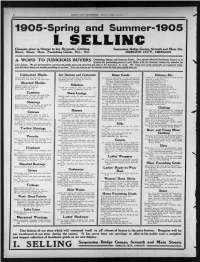

OREGON CITY ENTERPRISE, FRIDAY, APRIL 14, l!0o. (LflDTmOTTD On , Cheapest place in Oregon to buy Dry-goods- Clothing, Suspension Bridge Corner, Seventh and Main Sts. Boots, Shoes, Hats, Furnishing Goods, Etc., Etc. OREGON CITY, OREGON A. "WORD JUDICIOUS ' BUYERS Conccyning Spring and Summer Goods. Out special effort for the Spring Season is to TO increase the purchasing power of yof Dollar with the Greatest values ever afforded for your money." We are determined to convince the public more and more that out store is the best place to trade. We want yoar trade constantly and regularly when- ever the future finds you needing anything in out tine. Yog can always get the lowest prices for first class goods from ts Unbleached Muslin Art Denims and Cretonnes Dress Goods Notions, Etc. 36 inch wide, best LL, per yard, 5c. Art denims, 36 inch wide, per yard, 15e. Our line of dress goods for the Spring and Clark's O. N. T. spool cotton, 6 spools for 25o 36 inch wide, best Cabot W, per yard, 6y2c. Cretonnes, figured, oil finish, per yard, 8c. Summer of 1905 is a wonderful collection San silk, 2 spools for 5c. ' Twilled heavy, per yard, 10c. of elegant designs and fabrics of the newest Bone crochet hooks, 2 for 5c. Bleached Muslins and most popular fashions for the coming Knitting needles, set, 5c. season. Prices are uniformly low. Besf Eagle pins, 5c paper. Common quality, per yard, 5c. Silkoline 34 inch wide cashmere per yard 15c. Embroidery silk, 3 skeins for 10c. Medium grade, per yard, 7c. -

The British Linen Trade with the United States in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 1990 The British Linen Trade With The United States In The Eighteenth And Nineteenth Centuries N.B. Harte University College London Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Part of the Art and Design Commons Harte, N.B., "The British Linen Trade With The United States In The Eighteenth And Nineteenth Centuries" (1990). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 605. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/605 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. -14- THE BRITISH LINEN TRADE WITH THE UNITED STATES IN THE EIGHTEENTH AND NINETEENTH CENTURIES by N.B. HARTE Department of History Pasold Research Fund University College London London School of Economics Gower Street Houghton Street London WC1E 6BT London WC2A 2AE In the eighteenth century, a great deal of linen was produced in the American colonies. Virtually every farming family spun and wove linen cloth for its own consumption. The production of linen was the most widespread industrial activity in America during the colonial period. Yet at the same time, large amounts of linen were imported from across the Atlantic into the American colonies. Linen was the most important commodity entering into the American trade. This apparently paradoxical situation reflects the importance in pre-industrial society of the production and consumption of the extensive range of types of fabrics grouped together as 'linen*. -

Jews and Germans in Eastern Europe New Perspectives on Modern Jewish History

Jews and Germans in Eastern Europe New Perspectives on Modern Jewish History Edited by Cornelia Wilhelm Volume 8 Jews and Germans in Eastern Europe Shared and Comparative Histories Edited by Tobias Grill An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libra- ries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access. More information about the initiative can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org ISBN 978-3-11-048937-8 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-049248-4 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-048977-4 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial NoDerivatives 4.0 License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Grill, Tobias. Title: Jews and Germans in Eastern Europe : shared and comparative histories / edited by/herausgegeben von Tobias Grill. Description: [Berlin] : De Gruyter, [2018] | Series: New perspectives on modern Jewish history ; Band/Volume 8 | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2018019752 (print) | LCCN 2018019939 (ebook) | ISBN 9783110492484 (electronic Portable Document Format (pdf)) | ISBN 9783110489378 (hardback) | ISBN 9783110489774 (e-book epub) | ISBN 9783110492484 (e-book pdf) Subjects: LCSH: Jews--Europe, Eastern--History. | Germans--Europe, Eastern--History. | Yiddish language--Europe, Eastern--History. | Europe, Eastern--Ethnic relations. | BISAC: HISTORY / Jewish. | HISTORY / Europe / Eastern. Classification: LCC DS135.E82 (ebook) | LCC DS135.E82 J495 2018 (print) | DDC 947/.000431--dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018019752 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. -

Treasures of Culinary Heritage” in Upper Silesia As Described in the Most Recent Cookbooks

Teresa Smolińska Chair of Culture and Folklore Studies Faculty of Philology University of Opole Researchers of Culture Confronted with the “Treasures of Culinary Heritage” in Upper Silesia as Described in the Most Recent Cookbooks Abstract: Considering that in the last few years culinary matters have become a fashionable topic, the author is making a preliminary attempt at assessing many myths and authoritative opinions related to it. With respect to this aim, she has reviewed utilitarian literature, to which culinary handbooks certainly belong (“Con� cerning the studies of comestibles in culture”). In this context, she has singled out cookery books pertaining to only one region, Upper Silesia. This region has a complicated history, being an ethnic borderland, where after the 2nd World War, the local population of Silesians ��ac���������������������uired new neighbours����������������������� repatriates from the ����ast� ern Borderlands annexed by the Soviet Union, settlers from central and southern Poland, as well as former emigrants coming back from the West (“‘The treasures of culinary heritage’ in cookery books from Upper Silesia”). The author discusses several Silesian cookery books which focus only on the specificity of traditional Silesian cuisine, the Silesians’ curious conservatism and attachment to their regional tastes and culinary customs, their preference for some products and dislike of other ones. From the well�provided shelf of Silesian cookery books, she has singled out two recently published, unusual culinary handbooks by the Rev. Father Prof. Andrzej Hanich (Opolszczyzna w wielu smakach. Skarby dziedzictwa kulinarnego. 2200 wypróbowanych i polecanych przepisów na przysmaki kuchni domowej, Opole 2012; Smaki polskie i opolskie. Skarby dziedzictwa kulinarnego. -

Hunting Shirts and Silk Stockings: Clothing Early Cincinnati

Fall 1987 Clothing Early Cincinnati Hunting Shirts and Silk Stockings: Clothing Early Cincinnati Carolyn R. Shine play function is the more important of the two. Shakespeare, that fount of familiar quotations and universal truths, gave Polonius these words of advice for Laertes: Among the prime movers that have shaped Costly thy habit as thy purse can buy, But not expressed infancy; history, clothing should be counted as one of the most potent, rich not gaudy; For the apparel oft proclaims the man.1 although its significance to the endless ebb and flow of armed conflict tends to be obscured by the frivolities of Laertes was about to depart for the French fashion. The wool trade, for example, had roughly the same capital where, then as now, clothing was a conspicuous economic and political significance for the Late Middle indicator of social standing. It was also of enormous econo- Ages that the oil trade has today; and, closer to home, it was mic significance, giving employment to farmers, shepherds, the fur trade that opened up North America and helped weavers, spinsters, embroiderers, lace makers, tailors, button crack China's centuries long isolation. And think of the Silk makers, hosiers, hatters, merchants, sailors, and a host of others. Road. Across the Atlantic and nearly two hundred If, in general, not quite so valuable per pound years later, apparel still proclaimed the man. Although post- as gold, clothing like gold serves as a billboard on which to Revolution America was nominally a classless society, the display the image of self the individual wants to present to social identifier principle still manifested itself in the quality the world. -

Tourist Attractions

Tourist attractions Opole Silesia is an attractive region for every tourist and hiker. Due to its geographical location, it has long been a place of intersecting roads and trade routes. Historical factors have likewise made it a region open to migration and colonisation, as well as a place of asylum for religious refugees. In consequence, it has become a territory in which various cultures have mingled, in particular Polish, German, and Czech. Traces of these cultures and their transformations can be found in the architecture, handicraft and folklore of the region. The cultural heritage of Opole Silesia consists of architectural, folkloric, and natural wealth. Treasures of material culture – palaces, churches (including wooden ones), chapels, monuments, and technological monuments – often appear closely connected with the natural world. Parks, gardens, arboreta, zoological gardens and fishponds once were established in the close vicinity of palaces. Churches and chapels were accompanied with melliferous lime trees, which are now under protection. Sculptures of St. John Nepomucen once adorned bridges, rivers, or crossroads. Apart from an impressive number of man-made monuments, Opole Silesia also has natural monuments of exceptional value. In this respect, it belongs to the most important regions in Poland. There are many rare and endangered plant and animal species, unusual fossils, as well as numerous forms of inanimate nature, such as rivers picturesquely meandering in their natural river beds, springs, caves and the occasional boulder. The most valuable natural areas and objects are protected in landscape parks and nature reserves. Introduction 1 Moszna It is one of the youngest residential castles in Silesia, an architectural colossus (63000 m³ of cubic capacity, 7000 m² of surface area, 360 rooms, 99 turrets). -

![Kuchnia I Stół W Komunikacji Społecznej Kuchnia I Stół [...]Tematyka Kulinarna Zadomowiła Się Na Dobre W Prasie, Radiu, Telewizji I Internecie](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2418/kuchnia-i-st%C3%B3%C5%82-w-komunikacji-spo%C5%82ecznej-kuchnia-i-st%C3%B3%C5%82-tematyka-kulinarna-zadomowi%C5%82a-si%C4%99-na-dobre-w-prasie-radiu-telewizji-i-internecie-1212418.webp)

Kuchnia I Stół W Komunikacji Społecznej Kuchnia I Stół [...]Tematyka Kulinarna Zadomowiła Się Na Dobre W Prasie, Radiu, Telewizji I Internecie

Dyskurs, tekst, kultura tekst, Dyskurs, społecznej w komunikacji i stół Kuchnia Kuchnia i stół [...]Tematyka kulinarna zadomowiła się na dobre w prasie, radiu, telewizji i Internecie. Poradnictwo kulinarne zdominowało także blogosferę. W logosfe- rze wirtualnej obserwujemy ewolucję dyskursu kulinarnego w kierunku tekstów w komunikacji o nieostrym, eklektycznym wzorcu gatunkowo-stylistycznym, odwzorowującym indywidualne preferencje i upodobania wynikające z autorskich doświadczeń. Prezentowana monografi a gromadzi publikacje poddające obserwacji badaw- społecznej czej scenę kulinarną w perspektywie ewolucyjnej, aktualizowanej w komunikacji językowej i kulturowej. Analizie poddano zarówno zagadnienia sposobów rea- lizacji konkretnych gatunków mowy, jak też wzajemne ich zależności oraz uwa- Dyskurs, tekst, kultura runkowania. Książka uwzględnia wyniki badań nad problematyką kulinarną pro- wadzonych przez językoznawców, historyków, antropologów kultury, fi lozofów, bibliologów, historyków sztuki, literaturoznawców i medioznawców, postrzega- Redakcja naukowa jących jedzenie jako składnik dziedzictwa kulturowego w wymiarze domowym, regionalnym, narodowym i uniwersalnym. [...] Waldemar Żarski przy współpracy Ze wstępu. Tomasza Piaseckiego Kuchnia i stół w komunikacji społecznej Tekst, dyskurs, kultura Kuchnia i stół w komunikacji społecznej Tekst, dyskurs, kultura redakcja naukowa Waldemar Żarski przy współpracy Tomasza Piaseckiego Wrocław 2016 REDAKCJA NAUKOWA prof. dr hab. Waldemar Żarski przy współpracy dr. Tomasza Piaseckiego RECENZJA NAUKOWA -

![[Draft] Table of Contents](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4743/draft-table-of-contents-1264743.webp)

[Draft] Table of Contents

A Prussian Family’s Passage Through Leipzig [DRAFT] TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword v Scope and Objectives of this Study vii Events Timeline ix PART 1: A PRUSSIAN FAMILY’S PASSAGE THROUGH LEIPZIG 1 I. A CAST OF CHARACTERS: TOWARDS 1871 1 II. THE ROAD TO LEIPZIG: 1871-1878 17 III. ‘SOPHIE’S WORLD’: 1879-1899 33 IV. THE LONE RANGER FROM THE EAST: TOWARDS 1900 57 V. LEIPZIG: NEXUS: 1900-1907 75 VI. BABY BOOM, CLASS DISPUTES: 1907-1914 101 VII. CHAMPAGNE TO DIE FOR: 1914-1915 137 VIII. THE HOME FRONT: 1914-1918 171 IX. Pt.1: THE LOST GENERATION: 1919-1920 221 IX. Pt.2: WHAT WILL BECOME OF THE CHILDREN? 1920-1923 253 X. VOYAGE TO THE NEW WORLD: 1923-1927 293 XI. DIE GOLDENE ZWANZIGER: 1924-1929 339 XII. SEA CHANGE: 1927-1931 393 XIII. FAREWELL TO THE HEIMAT? 1930-1939 451 XIV. SOCIALIST TERROR: 1930-1939 451 XV. LIVES LESS ORDINARY: THE TALE OF TWO IRENES: 1939-1945 471 XVI. RISING FROM RUBBLE: 1945-1949 531 XVII. GERMANY (AND EUROPE) DIVIDED BY A WALL: 1949-1962 551 XVII. LIVING THE AMERICAN DREAM: 1963-1969 571 XVIII. A COUNTRY GARDEN: 1970-1982 599 XX. WINDS OF CHANGE: 1983-1990 631 PART 2: WANDERVÖGEL Nomads or Opportunists? 651 The Pull and Push of Leipzig 701 ANNEX: HOW WAS IT DONE? Afterword i © All text on this page copyrighted. No reproduction allowed without permission of the author. WANDERVÖGEL LIST OF TEXT BOXES 1.1: Networked Germany: The Rapid Rise of the Railways 7 2.1: Apprenticeships and Journeymen in Germany Today 19 2.2: Leipzig since the Middle Ages 24 2.3: The Schneider and His-story 25 2.4: The Innung – a new kind of Guild -

Textiles and Clothing the Macmillan Company

Historic, Archive Document Do not assume content reflects current scientific knowledge, policies, or practices. LIBRARY OF THE UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE C/^ss --SOA Book M l X TEXTILES AND CLOTHING THE MACMILLAN COMPANY NEW YORK • BOSTON • CHICAGO • DALLAS ATLANTA • SAN FRANCISCO MACMILLAN & CO., Limited LONDON • BOMBAY • CALCUTTA MELBOURNE THE MACMILLAN CO. OF CANADA, Ltd. TORONTO TEXTILES AXD CLOTHIXG BY ELLEX BEERS >McGO WAX. B.S. IXSTEUCTOR IX HOUSEHOLD ARTS TEACHERS COLLEGE. COLUMBIA U>aVERSITY AXD CHARLOTTE A. WAITE. M.A. HEAD OF DEPARTMENT OF DOMESTIC ART JULIA RICHMAX HIGH SCHOOL, KEW YORK CITY THE MACMILLAX COMPAXY 1919 All righU, reserved Copyright, 1919, By the MACMILLAN company. Set up and electrotyped. Published February, 1919. J. S. Gushing Co. — Berwick & Smith Co. Norwood, Mass., U.S.A. ; 155688 PREFACE This book has been written primarily to meet a need arising from the introduction of the study of textiles into the curriculum of the high school. The aim has been, there- fore, to present the subject matter in a form sufficiently simple and interesting to be grasped readily by the high school student, without sacrificing essential facts. It has not seemed desirable to explain in detail the mechanism of the various machines used in modern textile industries, but rather to show the student that the fundamental principles of textile manufacture found in the simple machines of primitive times are unchanged in the highl}^ developed and complicated machinerj^ of to-day. Minor emphasis has been given to certain necessarily technical paragraphs by printing these in type of a smaller size than that used for the body of the text. -

Subject Listing of Numbered Documents in M1934, OSS WASHINGTON SECRET INTELLIGENCE/SPECIAL FUNDS RECORDS, 1942-46

Subject Listing of Numbered Documents in M1934, OSS WASHINGTON SECRET INTELLIGENCE/SPECIAL FUNDS RECORDS, 1942-46 Roll # Doc # Subject Date To From 1 0000001 German Cable Company, D.A.T. 4/12/1945 State Dept.; London, American Maritime Delegation, Horta American Embassy, OSS; (Azores), (McNiece) Washington, OSS 1 0000002 Walter Husman & Fabrica de Produtos Alimonticios, "Cabega 5/29/1945 State Dept.; OSS Rio de Janeiro, American Embassy Branca of Sao Paolo 1 0000003 Contraband Currency & Smuggling of Wrist Watches at 5/17/1945 Washington, OSS Tangier, American Mission Tangier 1 0000004 Shipment & Movement of order for watches & Chronographs 3/5/1945 Pierce S.A., Switzerland Buenos Aires, American Embassy from Switzerland to Argentine & collateral sales extended to (Manufactures) & OSS (Vogt) other venues/regions (Washington) 1 0000005 Brueghel artwork painting in Stockholm 5/12/1945 Stockholm, British Legation; London, American Embassy London, American Embassy & OSS 1 0000006 Investigation of Matisse painting in possession of Andre Martin 5/17/1945 State Dept.; Paris, British London, American Embassy of Zurich Embassy, London, OSS, Washington, Treasury 1 0000007 Rubens painting, "St. Rochus," located in Stockholm 5/16/1945 State Dept.; Stockholm, British London, American Embassy Legation; London, Roberts Commission 1 0000007a Matisse painting held in Zurich by Andre Martin 5/3/1945 State Dept.; Paris, British London, American Embassy Embassy 1 0000007b Interview with Andre Martiro on Matisse painting obtained by 5/3/1945 Paris, British Embassy London, American Embassy Max Stocklin in Paris (vice Germans allegedly) 1 0000008 Account at Banco Lisboa & Acores in name of Max & 4/5/1945 State Dept.; Treasury; Lisbon, London, American Embassy (Peterson) Marguerite British Embassy 1 0000008a Funds transfer to Regerts in Oporto 3/21/1945 Neutral Trade Dept. -

VAN's Iduic Tip Top Market Reds Advance Within 91 Miles of Silesia

•> \. T H U R SD A T , a u g u s t 8,1944 1 M anh^ter Evening Herald Average Daily Circulation The W'eather leS.tWELVfi - For tbo Moath U Joly. 1S44 Foreeaet o f L . 8. Weotber Boreou the boyt to appear again this fall Workmen from the Connecticut HS the men at the hospital en Organ Recitals 8,728 Fair tonight nnd ^.^rday; l!t-i Miss EUa Shay. ' of Power Co. were working this Fine ProWam lie temperoture rhange# tonlghl; auffered a fractuit- of the leit ar n joyed the bouts very much. G. E. W ILLIS & SON, INC. morning on what they thlnx la the Feature Services Member of tbo Audit contlDued hot Soturdny. 'About Town ^ ^ a y when her horse sudjlcnly solution to the static InUrference Jtareaa of drcnlattoa# stoppU to eat grass at the road- baa been oauslng poor recep Given V^ts Lumber of All Kind* sIg*' S>h? And about eight other Gerarcl St. House Mancheeter— A City of Village Charm tion for radio Jiatenera within a A serie# of organ r e c lt ^ wiU iU r. and Mr*. WllUam 3. Helm, jriris had hired theU’ mounu from radius of one mile from the Cen Mason Supplies— Paint— Hardware the Adnsn Stables on tba new be played at the union aervlcea Jl W Cooper street, h*''^ "**" ter. A wire located on a pole oj^ N o^h End Boys’ Club Is Sold by Siiiilh (CIn##lfi#d AdverUalag «a Fa'go IS) MANCHESTER, CONN., FRIDAY, ‘AUGUST 4. 1944 (TWELVE PAGES) , PRICE THREE CENTS Stifled that their son, C orral Bolton road. -

Woven-To-Size Grassweave

GRASSWEAVE GRASSWEAVE An organic,An organic, modern modern mix mix of of refined refined toto rusticrustic textures,textures, hand crafted loomed with with artisanalartisanal technique technique to exquisiteto exquisite detail. detail. Handwoven Crafted with with sustainable sustainable blends blendsof grass of grass fibers, fibers, including including banana banana stem, stem, ramie, ramie, arrowroot, arrowroot, river river reed, reed,jute, jute, abaca, abaca, vetiver, vetiver, palm, palm, water water hyacinth, hyacinth, walingi walingi and and bamboo. bamboo. Grassweave [WTS] LE1006 Cambric LE1053 Silesia LE1062 Challis ELEMENTS Fresh, pure and timeless, this richly refined linen-like textile offers sophisticated beauty in a wide array of colorways ranging from neutral hues to dramatic darker tones, including Georgette a new rich black. LE1055 Sindon LE1052 Batiste LE1050 Sendal LE1015 Cambresine LE1054 Borato LE1084 Zephyr LE1087 Georgette NEW Price Group: 6 | Max Width: 180" Available Styles: Roman, Roller, Drapery, Top Treatment 037 | HARTMANNFORBES.COM | 888.582.8780 Shown: LE1050 Elements – Sendal, Old Style Roman Designer – Lindsay Anyon Brier, Anyon Interior Design | Photo – John Merkl Design – Brian del Toro, Inc | Photo – Marco Ricca Grassweave [WTS] TABARET Influenced by vintage European linen, this handwoven textile of ramie fiber offers subtle variegated stripes in nature’s hues, creating a harmonious mix of status and pedigree. LE2630 Lawn LE2660 Greylake LE2657 Lagoon LE2645 Brownstone Price Group: 6 | Max Width: 180" Available Styles: Roman, Roller, Drapery, Top Treatment Shown: LE2630 Tabaret – Lawn, Rollerfold Style 888.582.8780 | HARTMANNFORBES.COM | 040 Grassweave [WTS] GLIMMER This lustrous fine weave is ethereal, almost weightless, accented with micro hand knots that inject a pared-down luxe aesthetic.