The Beginnings of Indwstrialization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1/2 the Weather in Germany in Spring 2020 Exceptionally

The weather in Germany in spring 2020 Exceptionally sunny, fairly warm and far too dry Offenbach, 29 May 2020 – As in the previous year, the spring of 2020 was fairly warm. For most of the time, the weather in Germany was dominated by warm air, with just a few short cold snaps. At first, spring 2020 continued the trend of warmer-than-average months, which had started in June 2019 and only ended this May, when the temperature anomaly became slightly negative. Frequent high pressure produced one of the sunniest spring seasons since records began; at the same time, precipitation remained significantly below average. This has been announced by the Deutscher Wetterdienst (DWD) after an initial analysis of the observations from its approximately 2000 measuring stations. Mild March and warmer-than-average April followed by slightly too cool May The average temperature in the spring of 2020 was 9.2 degrees Celsius (°C), 1.5 °C above the average of the international standard reference period 1961–1990. Compared to the warmer 1981–2010 reference period, the deviation was 0.7 °C above normal. Spring began with a mild March, which, however, saw a drop in temperature around the 20th with maximum temperatures often not exceeding single-digit figures. April, too, was significantly too warm, even belonging to the seven warmest April months since measurements began in 1881. May was slightly too cool, despite some stations in the south registering up to seven summer days with temperatures over 25 °C. This spring’s nationwide maximum temperature of 29.4 °C was recorded in Lingen in the Emsland on 21 May. -

Schrifttum Über Ostbrandenburg Und Dessen Grenzgebiete 1964-1970 Bearbeitet Von Herbert Rister

Schrifttum über Ostbrandenburg und dessen Grenzgebiete 1964-1970 bearbeitet von Herbert Rister I. Allgemeines 1. Bibliographien 1. Wojew. i Miejska Bibl. Publ. w Zielonej Górze [u.a.]. Bibliografia Ziemi Lubuskiej. 1960. Oprać. Grzegorz Chmielewski. Zielona Góra 1966 (1967, Mai). XIV, 143 S. [Schrifttumsverz. d. Landes Lebus f. d. J. i960.] 2. Chmielewski, Grzegorz: Bibliografia archeologii Ziemi Lubuskiej <woj. zielonogórskiego> za 1. 1945—1964. In: Prace Lubuskiego Tow. Nauk. Nr 5. 1967. Mat. Komisji Archeolog. Nr 2. 1967. S. 112—129. [Bibliogr. z. Archäologie d. Landes Lebus, d. Woj. Grünberg, f. d. J. 1945—64.] 3. Chmielewski, Grzegorz: Bibliografia archeologii Ziemi Lubuskiej za r. 1965. In: Zielonogórskie zesz. muzealne 1. 1969. S. 213—215. [Bibliogr. z. Archäologie d. Landes Lebus f.d. J. 1965.] 4. Chmielewski, Grzegorz: Materiaùy do bibliografii ludności rodzimej Ziemi Lubuskiej. Wybór za lata 1945—1963. In: Roczn. lubuski. 4. 1966. S. 406—422. [Beitr. zu e. Schrifttumsverz. üb. d. bodenständige Bevölk. d. Landes Lebus. Auswahl f. d. Jahre 1945—63.] 5. Glubisz, Bohdan: „Sùowo żarskie". Wybór artykuùów poświęconych ziemi żarskiej. In: Żary wczoraj i dziś. Zielona Góra. 1967. S. 127—129. [Auswahl v. Aufsätzen üb. d. Sorauer Land aus d. Zeitung „Sorauer Wort".] 6. Heuser, Wilhelm: Veröffentlichungen des Instituts für Pflanzenbau u. Pflan• zenzüchtung in Landsberg/W. In: D. Preuß. Landwirtsch. Versuchs- u. For• schungsanstalten Landsberg/W. Würzb. 1968. S. 124—133. 7. Könekamp, Alfred Heinrich: Veröffentlichungen des Instituts für Grünland• wirtschaft. In: D. Preuß. Landwirtsch. Versuchs- u. Forschungsanstalten Lands• berg/W. Würzb. 1968. S. 175—183. 8. Rister, Herbert: Schrifttum über Ostbrandenburg u. dessen Grenzgebiete 1962—1963 mit Nachträgen. -

MITTEILUNGSBLATT Der Gemeinde Lauterach

MITTEILUNGSBLATT der Gemeinde Lauterach HERAUSGEBER: BÜRGERMEISTERAMT LAUTERACH Nr. 8/21.02.2020 Termine Grundschule Lauterach – Schulfasnet Freitag, 21.02.2020 SC Lauterach – Kaffeekränzchen im Sportheim Freitag, 21.02.2020 Fasnetsverein – Narrenmesse in der Pfarrkirche Neuburg Sonntag, 23.02.2020 Fasnetsverein – Fasnetseingrabung Dienstag, 25.02.2020 Landjugend Lauterach – Funkenfeuer Samstag, 29.02.2020 DRK Ortsverein Lauterach-Kirchen – Winterwanderung Sonntag, 01.03.2020 Biosphärengruppe Stammtisch im Infozentrum Montag, 02.03.2020 Biosphärengruppe – Weidenflechtkurs, Samstag, 07.03.2020 Anmeldung bis 29.02.2020 Öffnungszeiten Rathaus Das Sekretariat ist wie folgt geöffnet: Montag 24. Februar 2020 geschlossen (Rosenmontag) Dienstag, 25. Februar 2020 geschlossen (Fasnetsdienstag) Mittwoch, 26. Februar 2020 9 – 11 Uhr Donnerstag, 27. Februar 2020 9 – 11 Uhr und 15 – 18 Uhr Freitag, 28. Februar 2020 9 – 11 Uhr Wir bitten um Beachtung! Ihre Gemeindeverwaltung Zum Nachdenken Reich wird in Zukunft nicht der sein, der mehr hat, sondern der, der weniger braucht. Rainhard Fendrich ***************************************************************************************************************** Sprechzeiten der Gemeindeverwaltung: Montag von 9.00 bis 11.00 Uhr und 15.00 bis 18.00 Uhr Dienstag von 9.00 bis 11.00 Uhr Mittwoch von 9.00 bis 11.00 Uhr Donnerstag von 9.00 bis 11.00 Uhr und 15.00 bis 18.00 Uhr Freitag von 9.00 bis 11.00 Uhr Tel.: 07375 / 227 Fax 07375 /1549 eMail: [email protected] Homepage: www.Gemeinde-Lauterach.de Verantwortlich: Bürgermeister Bernhard Ritzler Tel.: 07375/536 - Redaktionsschluß Amtsblatt: Dienstag 8.00 Uhr eMail: [email protected] -2- Bericht aus der Gemeinderatsitzung vom 14. Februar 2020 TOP 1 Bürgerfragen Bei diesem Tagesordnungspunkt wurden aktuelle Bürgerfragen nicht gestellt. -

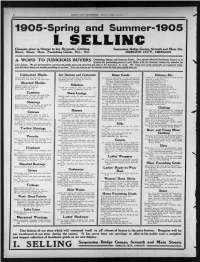

Suspension Bridge Corner, Seventh and Main Streets 3 I-- ' O LL G OREGON CITY, OREGON

OREGON CITY ENTERPRISE, FRIDAY, APRIL 14, l!0o. (LflDTmOTTD On , Cheapest place in Oregon to buy Dry-goods- Clothing, Suspension Bridge Corner, Seventh and Main Sts. Boots, Shoes, Hats, Furnishing Goods, Etc., Etc. OREGON CITY, OREGON A. "WORD JUDICIOUS ' BUYERS Conccyning Spring and Summer Goods. Out special effort for the Spring Season is to TO increase the purchasing power of yof Dollar with the Greatest values ever afforded for your money." We are determined to convince the public more and more that out store is the best place to trade. We want yoar trade constantly and regularly when- ever the future finds you needing anything in out tine. Yog can always get the lowest prices for first class goods from ts Unbleached Muslin Art Denims and Cretonnes Dress Goods Notions, Etc. 36 inch wide, best LL, per yard, 5c. Art denims, 36 inch wide, per yard, 15e. Our line of dress goods for the Spring and Clark's O. N. T. spool cotton, 6 spools for 25o 36 inch wide, best Cabot W, per yard, 6y2c. Cretonnes, figured, oil finish, per yard, 8c. Summer of 1905 is a wonderful collection San silk, 2 spools for 5c. ' Twilled heavy, per yard, 10c. of elegant designs and fabrics of the newest Bone crochet hooks, 2 for 5c. Bleached Muslins and most popular fashions for the coming Knitting needles, set, 5c. season. Prices are uniformly low. Besf Eagle pins, 5c paper. Common quality, per yard, 5c. Silkoline 34 inch wide cashmere per yard 15c. Embroidery silk, 3 skeins for 10c. Medium grade, per yard, 7c. -

NORTH RHINE WESTPHALIA 10 REASONS YOU SHOULD VISIT in 2019 the Mini Guide

NORTH RHINE WESTPHALIA 10 REASONS YOU SHOULD VISIT IN 2019 The mini guide In association with Commercial Editor Olivia Lee Editor-in-Chief Lyn Hughes Art Director Graham Berridge Writer Marcel Krueger Managing Editor Tom Hawker Managing Director Tilly McAuliffe Publishing Director John Innes ([email protected]) Publisher Catriona Bolger ([email protected]) Commercial Manager Adam Lloyds ([email protected]) Copyright Wanderlust Publications Ltd 2019 Cover KölnKongress GmbH 2 www.nrw-tourism.com/highlights2019 NORTH RHINE-WESTPHALIA Welcome On hearing the name North Rhine- Westphalia, your first thought might be North Rhine Where and What? This colourful region of western Germany, bordering the Netherlands and Belgium, is perhaps better known by its iconic cities; Cologne, Düsseldorf, Bonn. But North Rhine-Westphalia has far more to offer than a smattering of famous names, including over 900 museums, thousands of kilometres of cycleways and a calendar of exciting events lined up for the coming year. ONLINE Over the next few pages INFO we offer just a handful of the Head to many reasons you should visit nrw-tourism.com in 2019. And with direct flights for more information across the UK taking less than 90 minutes, it’s the perfect destination to slip away to on a Friday and still be back in time for your Monday commute. Published by Olivia Lee Editor www.nrw-tourism.com/highlights2019 3 NORTH RHINE-WESTPHALIA DID YOU KNOW? Despite being landlocked, North Rhine-Westphalia has over 1,500km of rivers, 360km of canals and more than 200 lakes. ‘Father Rhine’ weaves 226km through the state, from Bad Honnef in the south to Kleve in the north. -

REINER SOLENANDER (1524-1601): an IMPORTANT 16Th CENTURY MEDICAL PRACTITIONER and HIS ORIGINAL REPORT of VESALIUS’ DEATH in 1564

Izvorni znanstveni ~lanak Acta Med Hist Adriat 2015; 13(2);265-286 Original scientific paper UDK: 61(091)(391/399) REINER SOLENANDER (1524-1601): AN IMPORTANT 16th CENTURY MEDICAL PRACTITIONER AND HIS ORIGINAL REPORT OF VESALIUS’ DEATH IN 1564 REINER SOLENANDER (1524.–1601.): ZNAČAJAN MEDICINSKI PRAKTIČAR IZ 16. STOLJEĆA I NJEGOV IZVORNI IZVJEŠTAJ O VEZALOVOJ SMRTI 1564. GODINE Maurits Biesbrouck1, Theodoor Goddeeris2 and Omer Steeno3 Summary Reiner Solenander (1524-1601) was a physician born in the Duchy of Cleves, who got his education at the University of Leuven and at various universities in Italy and in France. Back at home he became the court physician of William V and later of his son John William. In this article his life and works are discussed. A report on the death of Andreas Vesalius (1514-1564), noted down by Solenander in May 1566, one year and seven months after the death of Vesalius, is discussed in detail. Due to the importance of that document a copy of its first publication is given, together with a transcription and a translation as well. It indicates that Vesalius did not die in a shipwreck. Key words: Solenander; Mercator; Vesalius; Zakynthos 1 Clinical Pathology, Roeselare (Belgium) member of the ISHM and of the SFHM. 2 Internal medicine - Geriatry, AZ Groeninge, Kortrijk (Belgium). 3 Endocrinology - Andrology, Catholic University of Leuven, member of the ISHM. Corresponding author: Dr. Maurits Biesbrouck. Koning Leopold III laan 52. B-8800 Roeselare. Belgium. Electronic address: [email protected] 265 Not every figure of impor- tance or interest for the bio- graphy of Andreas Vesalius was mentioned by him in his work1. -

Tourismus in Winterberg – Status Quo Und Perspektiven

E41_Layout 1 14.04.16 15:19 Seite 1 Stand: 2016 Tourismus in Winterberg – Status quo und Perspektiven Winterberg, touristische Hochburg Als PPP-Projekt bündelt das Oversum Wir sind schneesicher: Westfalens, hat in den letzten Jah- zahlreiche touristische Infrastruktur- Investitionen in die ren einen erheblichen Entwicklungs- einrichtungen (Tourist-Information, Wintersport-Infrastruktur schub erfahren. Im Jahr 2012 war Stadthalle, Schwimmbad , Hotel, Vor dem Hintergrund eines wetter- die „Ferienwelt Winterberg“ die Wellness-Anlage, Medizinisches Ver- bedingten Einbruchs im Winter- übernachtungsstärkste Destination sorgungszentrum). Das Hotel erfreut sporttourismus in den 1990er Jah- im Sauerland. Vor dem Hintergrund sich einer guten Auslastung und bil- ren wurde ein Maßnahmenplan ent- massiver Infrastrukturinvestitionen det eine wichtige Angebotsergän- wickelt, um künftig in einem wirt- betitelte eine Immobilien-Fachzeit- zung im sog. 4-Sterne-Superior-Seg- schaftlich tragfähigen Rahmen von schrift Winterberg gar als ment. Nicht in der amtlichen Statistik 80 Betriebstagen pro Saison Winter- „100 Mio.-Euro-Städtchen“. erfasst sind Betriebe mit weniger als sport zu ermöglichen. Zu den Maß- neun Betten. Daher ist von deutlich nahmen zählte die Gründung der Familiäre Atmosphäre und gelbe mehr Übernachtungen auszugehen, „Wintersport-Arena Sauerland“, Nummernschilder da in Winterberg nennenswerte einem Marketingverbund von mitt- Winterberg mit seinen 15 Ortsteilen Anteile an Privat- und Kleinvermie- lerweile 57 Skigebieten mit insge- und etwa -

Saxony: Landscapes/Rivers and Lakes/Climate

Freistaat Sachsen State Chancellery Message and Greeting ................................................................................................................................................. 2 State and People Delightful Saxony: Landscapes/Rivers and Lakes/Climate ......................................................................................... 5 The Saxons – A people unto themselves: Spatial distribution/Population structure/Religion .......................... 7 The Sorbs – Much more than folklore ............................................................................................................ 11 Then and Now Saxony makes history: From early days to the modern era ..................................................................................... 13 Tabular Overview ........................................................................................................................................................ 17 Constitution and Legislature Saxony in fine constitutional shape: Saxony as Free State/Constitution/Coat of arms/Flag/Anthem ....................... 21 Saxony’s strong forces: State assembly/Political parties/Associations/Civic commitment ..................................... 23 Administrations and Politics Saxony’s lean administration: Prime minister, ministries/State administration/ State budget/Local government/E-government/Simplification of the law ............................................................................... 29 Saxony in Europe and in the world: Federalism/Europe/International -

Employment Effects of Minimum Wages

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Neumark, David Article Employment effects of minimum wages IZA World of Labor Provided in Cooperation with: IZA – Institute of Labor Economics Suggested Citation: Neumark, David (2018) : Employment effects of minimum wages, IZA World of Labor, ISSN 2054-9571, Institute of Labor Economics (IZA), Bonn, Iss. 6v2, http://dx.doi.org/10.15185/izawol.6.v2 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/193409 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu DAVID NEUMARK University of California—Irvine, USA, and IZA, Germany Employment effects of minimum wages When minimum wages are introduced or raised, are there fewer jobs? Keywords: minimum wage, employment effects ELEVATOR PITCH Percentage differences between US state and The potential benefits of higher minimum wages come federal minimum wages, 2018 from the higher wages for affected workers, some of 80 whom are in poor or low-income families. -

Auf Tour Mit Dem Dem Mit Tour Auf

Blautopfbähnle Auf Tour mit dem in und um Blaubeuren, Schelklingen, Blaustein und Ulm Stadt Schelklingen, W.Wolf, A.Praefke, G.Griebener, D.Ohm u.a. D.Ohm G.Griebener, A.Praefke, W.Wolf, Schelklingen, Stadt W.Adler, M.Hangst, urmu Blaubeuren, Burkert, Wiedmann, E.Lehle, E.Lehle, Wiedmann, Burkert, Blaubeuren, urmu M.Hangst, W.Adler, Gestaltung: www.visuelles.de - Fotos: Auto-Mann, Stadt Blaubeuren, Blaubeuren, Stadt Auto-Mann, Fotos: - www.visuelles.de Gestaltung: EVENT-TOUREN Das besondere Highlight für spezielle Anlässe + SPECIALS Buchen Sie das nostalgische Blautopfbähnle als besonderes Highlight für Ihren speziellen Anlass ... Termine nach Absprache. Wir beraten Sie gerne. GESCHENK- Telefon 0 73 44 / 96 30 30 GUTSCHEIN • Unser Bähnle hat geschlossene und beheizbare Waggons, aus Sicherheitsgründen ist jedoch bei Eis und Schnee kein für eine Fahrt mit dem Betrieb möglich. Sollte eine Bähnlesfahrt auf Grund eines technischen Defekts, Unwetter oder Unbefahrbarkeit der nostalgischen Blautopfbähnle Wege nicht möglich sein, sind wir stets bemüht, Ihnen eine Alternative anzubieten. Ein Anspruch auf Ersatz besteht nicht. Hunde dürfen aus hygienischen Gründen leider nicht mitfahren. Fahrgeschwindigkeit maximal 25 km/h. Die angegebenen Preise gelten für 2017 Das besondere Highlight Touren Herzlich willkommen bei unseren Touren mit dem nostal- gischen Blautopfbähnle. Für Einzelgäste und Gruppen bieten für spezielle Anlässe wir das einmalige Erlebnis, auf einer Rundfahrt unsere wun- derschöne Stadt und das herrliche Umland kennenzulernen. Idyllische Täler und traumhafte Aussichtspunkte, schön gelege- ne Karstquellen, einzigartige Naturschätze und Sehenswürdig- keiten, Fundstellen aus der Steinzeit, das Biosphärengebiet bei Schelklingen ... Fahrgäste jeden Alters sind begeistert. Auf allen Touren bieten wir während der gemächlichen Fahrt vielfältige Informationen zu Orten und Sehenswürdigkeiten. -

Indicators of Hemeroby for the Monitoring of Landscapes in Germany

Indicators to monitor the structural diversity of landscapes Ulrich Walz Leibniz Institute of Ecological Urban and Regional Development, Weberplatz 1, 01217 Dresden, Germany Ecological Modelling 295 (2015) 88–106, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2014.07.011 ABSTRACT An important level of biodiversity, alongside the diversity of genes and species, is the diversity of ecosystems and landscapes. In this contribution an indicator system is proposed to measure natural diversity (relief, soils, waters), cultural diversity (main land use classes, diversity of land use, ecotones, connectivity) and anthropogenic impacts (fragmentation, hemeroby, protection).The contribution gives an overview of various indicators on landscape diversity and heterogeneity currently used in Germany andEurope. Based on these indicators a complementary system, is presented. The indicators introduced here are derived from regular evaluations of the digital basis landscape model (BasicDLM) of the Authoritative Topographic-Cartographic Information System (ATKIS), the digital land cover model for Germany (LBM-DE) as well as other supplementary data such as the mapping of potential natural vegetation. With the proposed indicators it is possible to estimate cumulative land-use change and its impact on the environmental status and biodiversity, so that existing indicator systems are supplemented with meaningful additional information. Investigations have shown that indicators on forest fragmentation, hemeroby or ecotones can be derived from official geodata. As such geodata is regularly updated, trends in indicator values can be quickly identified. Large regional differences in the distribution of the proposed indicators have been confirmed, thereby revealing deficits and identifying those regions with a high potential for biodiversity. The indicators will be successively integrated into the web-based land-use monitor (http://www.ioer-monitor.de), which is freely available for public use. -

The British Linen Trade with the United States in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 1990 The British Linen Trade With The United States In The Eighteenth And Nineteenth Centuries N.B. Harte University College London Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Part of the Art and Design Commons Harte, N.B., "The British Linen Trade With The United States In The Eighteenth And Nineteenth Centuries" (1990). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 605. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/605 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. -14- THE BRITISH LINEN TRADE WITH THE UNITED STATES IN THE EIGHTEENTH AND NINETEENTH CENTURIES by N.B. HARTE Department of History Pasold Research Fund University College London London School of Economics Gower Street Houghton Street London WC1E 6BT London WC2A 2AE In the eighteenth century, a great deal of linen was produced in the American colonies. Virtually every farming family spun and wove linen cloth for its own consumption. The production of linen was the most widespread industrial activity in America during the colonial period. Yet at the same time, large amounts of linen were imported from across the Atlantic into the American colonies. Linen was the most important commodity entering into the American trade. This apparently paradoxical situation reflects the importance in pre-industrial society of the production and consumption of the extensive range of types of fabrics grouped together as 'linen*.