The Passion Hymns

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Now Let Us Come Before Him Nun Laßt Uns Gehn Und Treten 8.8

Now Let Us Come Before Him Nun laßt uns gehn und treten 8.8. 8.8. Nun lasst uns Gott, dem Herren Paul Gerhardt, 1653 Nikolaus Selnecker, 1587 4 As mothers watch are keeping 9 To all who bow before Thee Tr. John Kelly, 1867, alt. Arr. Johann Crüger, alt. O’er children who are sleeping, And for Thy grace implore Thee, Their fear and grief assuaging, Oh, grant Thy benediction When angry storms are raging, And patience in affliction. 5 So God His own is shielding 10 With richest blessings crown us, And help to them is yielding. In all our ways, Lord, own us; When need and woe distress them, Give grace, who grace bestowest His loving arms caress them. To all, e’en to the lowest. 6 O Thou who dost not slumber, 11 Be Thou a Helper speedy Remove what would encumber To all the poor and needy, Our work, which prospers never To all forlorn a Father; Unless Thou bless it ever. Thine erring children gather. 7 Our song to Thee ascendeth, 12 Be with the sick and ailing, Whose mercy never endeth; Their Comforter unfailing; Our thanks to Thee we render, Dispelling grief and sadness, Who art our strong Defender. Oh, give them joy and gladness! 8 O God of mercy, hear us; 13 Above all else, Lord, send us Our Father, be Thou near us; Thy Spirit to attend us, Mid crosses and in sadness Within our hearts abiding, Be Thou our Fount of gladness. To heav’n our footsteps guiding. 14 All this Thy hand bestoweth, Thou Life, whence our life floweth. -

Document Cover Page

A Conductor’s Guide and a New Edition of Christoph Graupner's Wo Gehet Jesus Hin?, GWV 1119/39 Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Seal, Kevin Michael Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction, presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 09/10/2021 06:03:50 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/645781 A CONDUCTOR'S GUIDE AND A NEW EDITION OF CHRISTOPH GRAUPNER'S WO GEHET JESUS HIN?, GWV 1119/39 by Kevin M. Seal __________________________ Copyright © Kevin M. Seal 2020 A Document Submitted to the Faculty of the FRED FOX SCHOOL OF MUSIC In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2020 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Doctor of Musical Arts Document Committee, we certify that we have read the document prepared by: Kevin Michael Seal titled: A CONDUCTOR'S GUIDE AND A NEW EDITION OF CHRISTOPH GRAUPNER'S WO GEHET JESUS HIN, GWV 1119/39 and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the document requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. Bruce Chamberlain _________________________________________________________________ Date: ____________Aug 7, 2020 Bruce Chamberlain _________________________________________________________________ Date: ____________Aug 3, 2020 John T Brobeck _________________________________________________________________ Date: ____________Aug 7, 2020 Rex A. Woods Final approval and acceptance of this document is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the document to the Graduate College. -

Gesungene Aufklärung

Gesungene Aufklärung Untersuchungen zu nordwestdeutschen Gesangbuchreformen im späten 18. Jahrhundert Von der Carl von Ossietzky Universität Oldenburg – Fachbereich IV Human- und Gesellschaftswissenschaften – zur Erlangung des Grades einer Doktorin der Philosophie (Dr. phil.) genehmigte Dissertation von Barbara Stroeve geboren am 4. Oktober 1971 in Walsrode Referent: Prof. Dr. Ernst Hinrichs Korreferent: Prof. Dr. Peter Schleuning Tag der Disputation: 15.12.2005 Vorwort Der Anstoß zu diesem Thema ging von meiner Arbeit zum Ersten Staatsexamen aus, in der ich mich mit dem Oldenburgischen Gesangbuch während der Epoche der Auf- klärung beschäftigt habe. Professor Dr. Ernst Hinrichs hat mich ermuntert, meinen Forschungsansatz in einer Dissertation zu vertiefen. Mit großer Aufmerksamkeit und Sachkenntnis sowie konstruktiv-kritischen Anregungen betreute Ernst Hinrichs meine Promotion. Ihm gilt mein besonderer Dank. Ich danke Prof. Dr. Peter Schleuning für die Bereitschaft, mein Vorhaben zu un- terstützen und deren musiktheoretische und musikhistorische Anteile mit großer Sorgfalt zu prüfen. Mein herzlicher Dank gilt Prof. Dr. Hermann Kurzke, der meine Arbeit geduldig und mit steter Bereitschaft zum Gespräch gefördert hat. Manche Hilfe erfuhr ich durch Dr. Peter Albrecht, in Form von wertvollen Hinweisen und kritischen Denkanstößen. Während der Beschäftigung mit den Gesangbüchern der Aufklärung waren zahlreiche Gespräche mit den Stipendiaten des Graduiertenkollegs „Geistliches Lied und Kirchenlied interdisziplinär“ unschätzbar wichtig. Stellvertretend für einen inten- siven, inhaltlichen Austausch seien Dr. Andrea Neuhaus und Dr. Konstanze Grutschnig-Kieser genannt. Dem Evangelischen Studienwerk Villigst und der Deutschen Forschungsge- meinschaft danke ich für ihre finanzielle Unterstützung und Förderung während des Entstehungszeitraums dieser Arbeit. Ich widme diese Arbeit meinen Eltern, die dieses Vorhaben über Jahre bereit- willig unterstützt haben. -

Calmus Ensemble HALLELUJAH3

Calmus Ensemble Anja Pöche – Soprano Maria Kalmbach – Alto Friedrich Bracks – Tenor Ludwig Böhme – Baritone Manuel Helmeke – Bass HALLELUJAH3 Johann Sebastian Bach - Salomone Rossi – Leonard Cohen An exciting combination! And yet so obvious, because all three gave us one thing above all: songs! Spiritual songs full of passion, full of love and exultation, full of sadness and doubt. Songs full of spirituality and devotion that we can celebrate three times: Hallelujah1 The Psalms: the biblical origin, the songs of Solomon and David, originated over 2000 years ago. We sing them in settings by the Renaissance master Salomone Rossi, from his “Ha shirim asher li Shelomoh” (1623), the first collection of polyphonic synagogue music that has been written down in the ghetto in Mantua/Italy. Hallelujah2 Songs by Johann Sebastian Bach and Paul Gerhardt: They made faith more humane and are not missing in any hymn book today. Gerhardt's poetry and texts accompanies many people throughout their lives and in this program we’re going to sing it in artistic choral movements by Johann Sebastian Bach. Hallelujah3 Songs by Leonard Cohen: Of course, his famous “Hallelujah” should not be missing. But there is a lot more to discover with this great songwriter and poet. Coming from a Jewish family, faith and love were the great subjects of life for him. His songs are non-denominational, all-encompassing - and touching. Leonard Cohen Here it is (arr. Juan Garcia, *1976) 1934-2016 *** Johann Sebastian Bach Die güldne Sonne voll Freud und Wonne 1685-1750/ Movements: Johann Georg Ebeling (1637-1676), Paul Gerhardt Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750 ), from: Schemelli’s Song Book 1607-1676 Paul Gerhardt Salomone Rossi Psalm 146 (Haleluyah. -

Lutherans for Lent a Devotional Plan for the Season of Lent Designed to Acquaint Us with Our Lutheran Heritage, the Small Catechism, and the Four Gospels

Lutherans for Lent A devotional plan for the season of Lent designed to acquaint us with our Lutheran heritage, the Small Catechism, and the four Gospels. Rev. Joshua V. Scheer 52 Other Notables (not exhaustive) The list of Lutherans included in this devotion are by no means the end of Lutherans for Lent Lutheranism’s contribution to history. There are many other Lutherans © 2010 by Rev. Joshua V. Scheer who could have been included in this devotion who may have actually been greater or had more influence than some that were included. Here is a list of other names (in no particular order): Nikolaus Decius J. T. Mueller August H. Francke Justus Jonas Kenneth Korby Reinhold Niebuhr This copy has been made available through a congregational license. Johann Walter Gustaf Wingren Helmut Thielecke Matthias Flacius J. A. O. Preus (II) Dietrich Bonheoffer Andres Quenstadt A.L. Barry J. Muhlhauser Timotheus Kirchner Gerhard Forde S. J. Stenerson Johann Olearius John H. C. Fritz F. A. Cramer If purchased under a congregational license, the purchasing congregation Nikolai Grundtvig Theodore Tappert F. Lochner may print copies as necessary for use in that congregation only. Paul Caspari August Crull J. A. Grabau Gisele Johnson Alfred Rehwinkel August Kavel H. A. Preus William Beck Adolf von Harnack J. A. O. Otteson J. P. Koehler Claus Harms U. V. Koren Theodore Graebner Johann Keil Adolf Hoenecke Edmund Schlink Hans Tausen Andreas Osiander Theodore Kliefoth Franz Delitzsch Albrecht Durer William Arndt Gottfried Thomasius August Pieper William Dallman Karl Ulmann Ludwig von Beethoven August Suelflow Ernst Cloeter W. -

The Translation of German Pietist Imagery Into Anglo-American Cultures

Copyright by Ingrid Goggan Lelos 2009 The Dissertation Committee for Ingrid Goggan Lelos Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: The Spirit in the Flesh: The Translation of German Pietist Imagery into Anglo-American Cultures Committee: Katherine Arens, Supervisor Julie Sievers, Co-Supervisor Sandy Straubhaar Janet Swaffar Marjorie Woods The Spirit in the Flesh: The Translation of German Pietist Imagery into Anglo-American Cultures by Ingrid Goggan Lelos, B.A.; M.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2009 Dedication for my parents, who inspired intellectual curiosity, for my husband, who nurtured my curiositities, and for my children, who daily renew my curiosities Acknowledgements I would like to express my gratitude to so many who made this project possible. First, I must thank Katie Arens, who always believed in me and faithfully guided me through this journey across centuries and great geographic expanses. It is truly rare to find a dissertation advisor with the expertise and interest to direct a project that begins in medieval Europe and ends in antebellum America. Without her belief in the study of hymns as literature and the convergence of religious and secular discourses this project and its contributions to scholarship would have remained but vague, unarticulated musings. Without Julie Sievers, this project would not have its sharpness of focus or foreground so clearly its scholarly merits, which she so graciously identified. -

Risen Savior Lutheran Church

Risen Savior Lutheran 2018 Church Pastor Art in the Lord’s House Key Our last stained-glass windows and additional wood carvings perhaps will be coming soon… Events The Lutheran Reformation did not simply destroy what came before it. The Confessions make it clear that we retain and preserve what we can according to the Gospel, as in these examples, which our congregations and Synod are still bound: Oct. 7 ➔ “We keep traditional liturgical forms, such as the order of the lessons, prayers, Oktoberfest vestments, etc.” (Apology XXIV). ➔ “Those ancient customs should be kept which can be kept without sin or without great Oct. 13 disadvantage. This is what we teach….We gladly keep the old traditions set up in the Highway church because they are useful and promote tranquility …the children chant the Psalms in order to learn.” (Apology XV). Clean-up ➔ “The [Service] is retained among us and is celebrated with the greatest reverence. Almost all the customary ceremonies are also retained.” (Augsburg Confession XXIV) Oct. 15 In many cases this applied to the visual arts as well. While Great Britain and Switzerland Blood Drive bear the scars of Reformed iconoclasm, many churches in Lutheran Germany still display the beauty of medieval Christianity. Art is like worship. In a practical, utilitarian world it seems rather useless and perhaps Oct. 28 even foolish, even a waste of money. Art is just pretty stuff, the things we hang up in our Festival of the homes to decorate the plain wall. It has meaning only so long as we choose it to and it is Reformation something we discard when we are over it or when our interests or tastes change. -

Kirchenlieder Im Bass-Schlüssel

Kirchenlieder im Bass-Schlüssel Passion und Ostern Inhalt Einführung 3 Lieder Passion EG-Nr. Titel 79 Wir danken dir, Herr Jesu Christ, dass du für uns gestorben bist 4 80 O Traurigkeit, o Herzeleid 4 81 Herzliebster Jesu 4 85 O Haupt voll Blut und Wunden 5 Ostern 99 Christ ist erstanden 6 100 Wir wollen alle fröhlich sein 7 103 Gelobt sei Gott im höchsten Thron 7 105 Erstanden ist der heilig Christ 7 106 Erschienen ist der herrlich Tag 8 107 Wir danken dir, Herr Jesu Christ 8 110 Die ganze Welt, Herr Jesu Christ 8 111 Frühmorgens, da die Sonn aufgeht 8 112 Auf, auf, mein Herz mit Freuden 9 115 Jesus lebt, mit ihm auch ich 9 2 Einführung Tiefe Instrumente sind wichtig für das Fundament der Musik, deswegen übernehmen sie eher sel- ten die Melodie. Dabei möchten auch Bassist*innen gerne einmal die Hauptstimme spielen. Besonders in den Zeiten, in denen das mehrstimmige Spielen eingeschränkt und das Gottesdienst- und Kurrendeblasen nur in Kleinstbesetzung möglich ist, kann die Melodie solistisch von einem tie- fen Instrument oder vom tiefen Register übernommen werden. Bassist*innen spielen in der Regel im Bass-Schlüssel. Deshalb hat Landesposaunenwart Frank Vo- gel bekannte Kirchenlieder zu Passion und Ostern aus dem Evangelischen Gesangbuch (EG) in den Bass-Schlüssel übertragen. Gerne stellen wir Ihnen dieses Heft zur Verfügung, das nicht nur von den tiefen Stimmen des Po- saunenchores, sondern von allen anderen Instrumenten der tiefen Lage genutzt werden. Für das gemeinsame Musizieren mit Sänger*innen und anderen Instrumentalist*innen verweisen wir auf die TÖNE 6 "Kirchenlieder zu Passion und Ostern". -

Introduction

INTRODUCTION Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach’s Passion according to St. Maria, was asked by the church authorities in a question- John, H 793 (BR-CPEB D 7.), performed during Lent naire about the sources of the poetry in her late husband’s 1780, was his twelfth Passion and his third setting of John’s music. Question 9 and her answer read: Passion narrative. His estate catalogue (NV 1790, p. 60) [Question] 9. Whether or not he had provided the poetry for lists the dates of composition as 1779–80: “Paßions Musik the music and how he did this? nach dem Evangelisten Johannes. H. 1779 und 1780. Mit [Answer] 9. He received some from good friends, and some Hörnern, Hoboen und Fagotts.” Four years earlier, in 177, were taken from printed books. For installation cantatas the Bach had used the St. John Passion by Gottfried August poet, as far as I know, was sometimes paid by the respective Homilius, HoWV I., for much of the biblical narra- church or the pastor; but this was not always the case. In tive and two of the chorales, but in his last three settings these instances the text was often submitted in writing. In of the St. John Passion (1780, 178, and 1788), Bach re- short, there is no set procedure in this respect.1 turned to Georg Philipp Telemann’s 17 St. John Passion, TVWV 5:30, which he had used as the basis for his first Naturally, some of the choruses can be traced to Psalms or setting of 177. But Bach rarely reused any of the arias, du- other biblical texts, and in his later years Bach also drew ets, or choruses in his Passions, and so the overall impres- more frequently on his songs as the basis for both arias sion is that each of his twenty-one Passions is a separate and choruses. -

Bibliografie

Veröffentlichungen: Prof. Dr. Inge Mager 1) Georg Calixts theologische Ethik und ihre Nachwirkungen, SKGNS 19, Göttingen 1969 2) Georg Calixt, Werke in Auswahl, Bd. 3: Ethische Schriften, Göttingen 1970 3) Theologische Promotionen an der Universität Helmstedt im ersten Jahrhundert des Bestehens, JGNKG 69, 1971, 83–102 4) Georg Calixt, Werke in Auswahl, Bd. 4: Schriften zur Eschatologie, Göttingen 1972 5) Conrad Hornejus, NDB 9, 1972, 637f. 6) Lutherische Theologie und aristotelische Philosophie an der Universität Helmstedt im 16. Jahrhundert. Zur Vorgeschichte des Hofmannschen Streites im Jahre 1598, JGNKG 73, 1975, 83–98 7) Bibliographie zur Geschichte der Universität Helmstedt, JGNKG 74, 1976, 237–242 8) Reformatorische Theologie und Reformationsverständnis an der Universität Helmstedt im 16. und 17. Jahrhundert, JGNKG 74, 1976, 11–33 9) Timotheus Kirchner, NDB 11, 1977, 664f. 10) Das Corpus Doctrinae der Stadt Braunschweig im Gefüge der übrigen niedersächsischen Lehrschriftensammlungen, in: Die Reformation in der Stadt Braunschweig. Festschrift 1528–1978, Braunschweig 1978, 111–122.139–143 11) Georg Calixt, Werke in Auswahl, Bd. 1: Einleitung in die Theologie, Göttingen 1978 12) Die Beziehung Herzog Augusts von Braunschweig–Wolfenbüttel zu den Theologen Georg Calixt und Johann Valentin Andreae, in: Pietismus und Neuzeit 6, Göttingen 1980, 76–98 13) Calixtus redivivus oder Spaltung und Versöhnung. Das Hauptwerk des nordfriesischen Theologen Heinrich Hansen und die Gründung der Hochkirchlichen Vereinigung im Jahre 1918, Nordfries. Jb., N.F. 16, 1980, 127–139 14) Aufnahme und Ablehnung des Konkordienbuches in Nord–, Mittel– und Ostdeutschland, in: Bekenntnis und Einheit der Kirche, hrsg. v. M.Brecht u. R.Schwarz, Stuttgart 1980, 271–302 15) Brüderlichkeit und Einheit. -

Sofia Gubaidulina and Wolfgang Rihm

THEOLOGY OF BEAUTY Rocznik Teologii Katolickiej, tom XVII/1, rok 2018 DOI: 10.15290/rtk.2018.17.1.12 0000-0001-6701-1378 Joanna Cieślik-Klauza Uniwersytet Muzyczny Fryderyka Chopina Passion Music at the Turn of the XX and XXI Centuries, Part I: Sofia Gubaidulina and Wolfgang Rihm The great conductor and scholar of the works of Bach, Helmuth Rilling, com- missioned his colleague composers from different countries to write works on the Passion of Christ inspired by the four Gospels. This project known as Passion 2000 was realized on the 250th anniversary of Bach’s death. As part of this valuable initiative and tribute to the Bach, the Russian composer Sofia Gubaidulina, the German composer Wolfgang Rihm, the Chinese composer Tan Dun, and the Argentinian composer Osvaldo Goliovo created four considerable works that completely differ stylistically and provide new perspectives onPas - sion settings. This article presents the following two European Passions from a historical perspective: the St. John Passion by Sofia Gubaidulina and the Deus Passus by Wolfgang Rihm. These composers’ perspectives of the Passion genre expand the traditional framework of this genre as they present the events of the Passion within contemporary contexts and combine musical styles from different historical periods. Key words: Passion, Wolfgang Rihm, Sofia Gubaidulina, contemporary sacred music, St. John Passion, Deus Passus. One cannot remain indifferent to the topic of the Passion. Every year for centuries, cultures and traditions have recalled the revelation of the mystery of the cross, the sorrow of the Mother of God, and the sacrifice of Jesus Christ. This teaching arises from the moment that is the most important to Christians: the Death and Resurrection of 184 Joanna Cieślik-Klauza Christ. -

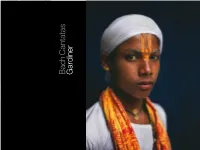

B Ach C Antatas G Ardiner

Johann Sebastian Bach 1685-1750 Cantatas Vol 3: Tewkesbury/Mühlhausen SDG141 COVER SDG141 CD 1 76:03 For the Fourth Sunday after Trinity Ein ungefärbt Gemüte BWV 24 Barmherziges Herze der ewigen Liebe BWV 185 Ich ruf zu dir, Herr Jesu Christ BWV 177 Magdalena Kozˇená soprano, Nathalie Stutzmann alto Paul Agnew tenor, Nicolas Teste bass For the Fifth Sunday after Trinity Gott ist mein König BWV 71 C CD 2 62:12 Aus der Tiefen rufe ich, Herr, zu dir BWV 131 M Wer nur den lieben Gott lässt walten BWV 93 Y Siehe, ich will viel Fischer aussenden BWV 88 K Joanne Lunn soprano, William Towers alto Kobie van Rensburg tenor, Peter Harvey bass The Monteverdi Choir The English Baroque Soloists John Eliot Gardiner Live recordings from the Bach Cantata Pilgrimage Tewkesbury Abbey, 16 July 2000 Blasiuskirche, Mühlhausen, 23 July 2000 Soli Deo Gloria Volume 3 SDG 141 P 2008 Monteverdi Productions Ltd C 2008 Monteverdi Productions Ltd www.solideogloria.co.uk Edition by Reinhold Kubik, Breitkopf & Härtel Manufactured in Italy LC13772 8 43183 01412 5 SDG 141 Bach Cantatas Gardiner 3 Bach Cantatas Gardiner CD 1 76:03 For the Fourth Sunday after Trinity 1-6 17:01 Ein ungefärbt Gemüte BWV 24 7-12 14:41 Barmherziges Herze der ewigen Liebe BWV 185 13-17 25:06 Ich ruf zu dir, Herr Jesu Christ BWV 177 BWV 24, 185, 177 Magdalena Kozˇená soprano, Nathalie Stutzmann alto The Monteverdi Choir The English Double Bass Harpsichord Baroque Soloists Valerie Botwright Howard Moody Sopranos Paul Agnew tenor, Nicolas Teste bass Cecelia Bruggemeyer Lucinda Houghton First Violins