Evangelism and Capitalism: a Reparative Account and Diagnosis of Pathogeneses in the Relationship

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report from 1 August 2010

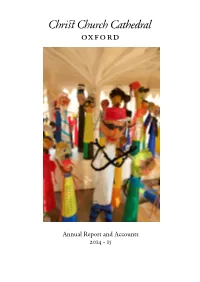

6 Annual Report and Accounts 2014 - 15 Annual Report August 2014 - July 2015 Introduction Christ Church Cathedral was, as ever, full of exciting activities and events during 2014 - 15, the most significant of which was the appointment of a new Dean, Martyn Percy, who replaced Christopher Lewis on his retirement in September 2014 after eleven years at the helm. Martyn became the forty-sixth Dean of Christ Church since its establishment by Henry VIII in 1546. This year’s cover illustration features the summer 2014 art installation of paper pilgrims produced by Summerfield School pupils displayed in our 15th century watching loft, situated between the Latin Chapel and the Lady Chapel. Worship There are between three and six regular Cathedral services every day of the year. Our congregations are varied: supporting a core of regular worshippers are a significant number of tourists visiting Christ Church from around the world. The Cathedral’s informal Sunday evening reflective service, After Eight, continued throughout the Michaelmas and Hilary terms and covered a wide range of topics. These included ‘A Particular Place’, focusing on a location of special spiritual significance to each of four speakers, ‘Enduring War … Engaging with Peace’, addressing present day conflicts, and ‘When I needed a Neighbour’, a series of dialogues on Christian ministry at the margins of modern life. There were many special events and services among them the following: • Our new year was ushered in with a reminder of the First World War. The centenary of the outbreak -

A Brief History of Christ Church MEDIEVAL PERIOD

A Brief History of Christ Church MEDIEVAL PERIOD Christ Church was founded in 1546, and there had been a college here since 1525, but prior to the Dissolution of the monasteries, the site was occupied by a priory dedicated to the memory of St Frideswide, the patron saint of both university and city. St Frideswide, a noble Saxon lady, founded a nunnery for herself as head and for twelve more noble virgin ladies sometime towards the end of the seventh century. She was, however, pursued by Algar, prince of Leicester, for her hand in marriage. She refused his frequent approaches which became more and more desperate. Frideswide and her ladies, forewarned miraculously of yet another attempt by Algar, fled up river to hide. She stayed away some years, settling at Binsey, where she performed healing miracles. On returning to Oxford, Frideswide found that Algar was as persistent as ever, laying siege to the town in order to capture his bride. Frideswide called down blindness on Algar who eventually repented of his ways, and left Frideswide to her devotions. Frideswide died in about 737, and was canonised in 1480. Long before this, though, pilgrims came to her shrine in the priory church which was now populated by Augustinian canons. Nothing remains of Frideswide’s nunnery, and little - just a few stones - of the Saxon church but the cathedral and the buildings around the cloister are the oldest on the site. Her story is pictured in cartoon form by Burne-Jones in one of the windows in the cathedral. One of the gifts made to the priory was the meadow between Christ Church and the Thames and Cherwell rivers; Lady Montacute gave the land to maintain her chantry which lay in the Lady Chapel close to St Frideswide’s shrine. -

Investigation of the Idea of Nestorian Crosses— Based on Fa Nixon's

QUEST: Studies on Religion & Culture in Asia, Vol. 2, 2017 INVESTIGATION OF THE IDEA OF NESTORIAN CROSSES— BASED ON F. A. NIXON’S COLLECTION Chen, Jian Andrea Published online: 1 January 2017 ABSTRACT It is generally agreed that the study of the Nestorian Cross (a kind of bronze piece believed to be an early Chinese Christian relic), has great significance both for the developing study of Jingjiao and for ethnographic studies of the Nestorian Mongol people. The most important question that we should ask, however, is, “Are these so-called Nestorian Crosses part of the Mongolian Nestorian heritage?“ In other words, before starting to interpret the pieces in question, we need to ask if the identification, made at the first step of examination, is convincing enough as a basis upon which to build the interpretation. This paper focuses on issues concerning all aspects of the concept of Nestorian Crosses, looking first into the history of such an idea, then investigating its inner logic, and finally challenging its hard evidence. It is hoped that the conclusions of this paper will initiate a paradigm shift in the current study of this topic. Introduction to the Study The Jingjiao and the Yelikewen The name “Nestorian Crosses” clearly reveals that the religious dimension has been the primary consideration in the existing identification of these items, an identification which subsumes them as relics of Chinese Nestorianism, or more accurately, of the Jingjiao and the Yelikewen. Although controversies surround the identity of Nestorianism, the most commonly accepted description is as follows: At the Ephesus Council of 431 A.D., the Patriarch Nestorius was deemed heretical and his teaching anathematized due to his insistence that Mary should be called “Christotokos (Christ-bearer)” instead of “Theotokos (God-bearer).” This insistence is thought to emphasize a distinction between Christ’s divine and human natures instead of their unity. -

Ecclesiology of the Anglican Communion: Rediscovering the Radical and Transnational Nature of the Anglican Communion

A (New) Ecclesiology of the Anglican Communion: Rediscovering the Radical and Transnational Nature of the Anglican Communion Guillermo René Cavieses Araya Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds Faculty of Arts School of Philosophy, Religion and History of Science February 2019 1 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from this thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. © 2019 The University of Leeds and Guillermo René Cavieses Araya The right of Guillermo René Cavieses Araya to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by Guillermo René Cavieses Araya in accordance with the Copyright, Design and Patents Act 1988. 2 Acknowledgements No man is an island, and neither is his work. This thesis would not have been possible without the contribution of a lot of people, going a long way back. So, let’s start at the beginning. Mum, thank you for teaching me that it was OK for me to dream of working for a circus when I was little, so long as I first went to University to get a degree on it. Dad, thanks for teaching me the value of books and a solid right hook. To my other Dad, thank you for teaching me the virtue of patience (yes, I know, I am still working on that one). -

Alternative Heroes in Nineteenth-Century Historical Plays

DOI 10.6094/helden.heroes.heros./2014/01/02 Dorothea Flothow 5 Unheroic and Yet Charming – Alternative Heroes in Nineteenth-Century Historical Plays It has been claimed repeatedly that unlike previ- MacDonald’s Not About Heroes (1982) show ous times, ours is a post-heroic age (Immer and the impossibility of heroism in modern warfare. van Marwyck 11). Thus, we also fi nd it diffi cult In recent years, a series of bio-dramas featuring to revere the heroes and heroines of the past. artists, amongst them Peter Shaffer’s Amadeus In deed, when examining historical television se- (1979) and Sebastian Barry’s Andersen’s En- ries, such as Blackadder, it is obvious how the glish (2010), have cut their “artist-hero” (Huber champions of English imperial history are lam- and Middeke 134) down to size by emphasizing pooned and “debunked” – in Blackadder II, Eliz- the clash between personal action and high- abeth I is depicted as “Queenie”, an ill-tempered, mind ed artistic idealism. selfi sh “spoiled child” (Latham 217); her immor- tal “Speech to the Troops at Tilbury” becomes The debunking of great historical fi gures in re- part of a drunken evening with her favourites cent drama is often interpreted as resulting par- (Epi sode 5, “Beer”). In Blackadder the Third, ticularly from a postmodern infl uence.3 Thus, as Horatio Nelson’s most famous words, “England Martin Middeke explains: “Postmodernism sets expects that every man will do his duty”, are triv- out to challenge the occidental idea of enlighten- ialized to “England knows Lady Hamilton is a ment and, especially, the cognitive and episte- virgin” (Episode 2, “Ink and Incapability”). -

Chris Church Matters

Chris Church Matters MICHAELMAS TERM 2014 ISSUE 34 Editorial Contents In this Michaelmas edition we welcome our 45th Dean, the Very Revd Professor Dean’s Diary 1 Martyn Percy, who joined us in October after ten years as Principal of Ripon College Cuddesdon. We also say goodbye to our former Dean, Christopher Lewis, and his wife Goodbye from Chrsitopher Lewis 2 Rhona as they retire to the idyllic Suffolk coast. Much has been achieved in this year Cardinal Sins 6 of change, and we celebrate the successes of members past and present in this issue. If you have news of your own which you would like to share with the Christ Church Christ Church Cathedral Choir 8 community, we invite you to make a submission to the next Annual Report – details Cathedral News 9 of this can be found in College News. A new Christ Church website will be launched in the spring, and with this a new Christ Church People: digital platform for Christ Church Matters. If you would like to receive the magazine Phyllis May Bursill 10 digitally, please let us know. Conservation work We wish you a wonderful Christmas and New Year, and hope to see you in 2015. on the Music Collection 12 Simon Offen Leia Clancy Cathedral School 14 Christ Church Association Alumni Relations Officer Vice President and Deputy [email protected] College News 16 Development Director +44 (0)1865 286 598 [email protected] Boat Club News 18 +44 (0)1865 286 075 Association News 19 FORTHCOMING EVENTS Sensible Religion: A Review 29 Event booking forms are available to download at www.chch.ox.ac.uk/development/events/future The Paper Project at Ovalhouse 30 MARCH 2015 APRIL 2015 SEPTEMBER 2015 Robert Hooke’s Micrographia 32 14 March 24-26 April 12 September FAMILY PROGRAMME LUNCH MEETING MINDS: ALUMNI BOARD OF BENEFACTORS GAUDY Who should decide on war? 34 Christ Church WEEKEND IN VIENNA Christ Church Parents of current or former All are invited to join us for 18-20 September Christ Church Gardens 30 students are invited to lunch at three days of alumni activities MEETING MINDS: ALUMNI Christ Church. -

Nestorianism 1 Nestorianism

Nestorianism 1 Nestorianism For the church sometimes known as the Nestorian Church, see Church of the East. "Nestorian" redirects here. For other uses, see Nestorian (disambiguation). Nestorianism is a Christological doctrine advanced by Nestorius, Patriarch of Constantinople from 428–431. The doctrine, which was informed by Nestorius' studies under Theodore of Mopsuestia at the School of Antioch, emphasizes the disunion between the human and divine natures of Jesus. Nestorius' teachings brought him into conflict with some other prominent church leaders, most notably Cyril of Alexandria, who criticized especially his rejection of the title Theotokos ("Bringer forth of God") for the Virgin Mary. Nestorius and his teachings were eventually condemned as heretical at the First Council of Ephesus in 431 and the Council of Chalcedon in 451, leading to the Nestorian Schism in which churches supporting Nestorius broke with the rest of the Christian Church. Afterward many of Nestorius' supporters relocated to Sassanid Persia, where they affiliated with the local Christian community, known as the Church of the East. Over the next decades the Church of the East became increasingly Nestorian in doctrine, leading it to be known alternately as the Nestorian Church. Nestorianism is a form of dyophysitism, and can be seen as the antithesis to monophysitism, which emerged in reaction to Nestorianism. Where Nestorianism holds that Christ had two loosely-united natures, divine and human, monophysitism holds that he had but a single nature, his human nature being absorbed into his divinity. A brief definition of Nestorian Christology can be given as: "Jesus Christ, who is not identical with the Son but personally united with the Son, who lives in him, is one hypostasis and one nature: human."[1] Both Nestorianism and monophysitism were condemned as heretical at the Council of Chalcedon. -

DISSERTATION-Submission Reformatted

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Dilemma of Obedience: Persecution, Dissimulation, and Memory in Early Modern England, 1553-1603 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5tv2w736 Author Harkins, Robert Lee Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Dilemma of Obedience: Persecution, Dissimulation, and Memory in Early Modern England, 1553-1603 By Robert Lee Harkins A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Ethan Shagan, Chair Professor Jonathan Sheehan Professor David Bates Fall 2013 © Robert Lee Harkins 2013 All Rights Reserved 1 Abstract The Dilemma of Obedience: Persecution, Dissimulation, and Memory in Early Modern England, 1553-1603 by Robert Lee Harkins Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Berkeley Professor Ethan Shagan, Chair This study examines the problem of religious and political obedience in early modern England. Drawing upon extensive manuscript research, it focuses on the reign of Mary I (1553-1558), when the official return to Roman Catholicism was accompanied by the prosecution of Protestants for heresy, and the reign of Elizabeth I (1558-1603), when the state religion again shifted to Protestantism. I argue that the cognitive dissonance created by these seesaw changes of official doctrine necessitated a society in which religious mutability became standard operating procedure. For most early modern men and women it was impossible to navigate between the competing and contradictory dictates of Tudor religion and politics without conforming, dissimulating, or changing important points of conscience and belief. -

DISSERTATION-Submission Reformatted

The Dilemma of Obedience: Persecution, Dissimulation, and Memory in Early Modern England, 1553-1603 By Robert Lee Harkins A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Ethan Shagan, Chair Professor Jonathan Sheehan Professor David Bates Fall 2013 © Robert Lee Harkins 2013 All Rights Reserved 1 Abstract The Dilemma of Obedience: Persecution, Dissimulation, and Memory in Early Modern England, 1553-1603 by Robert Lee Harkins Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Berkeley Professor Ethan Shagan, Chair This study examines the problem of religious and political obedience in early modern England. Drawing upon extensive manuscript research, it focuses on the reign of Mary I (1553-1558), when the official return to Roman Catholicism was accompanied by the prosecution of Protestants for heresy, and the reign of Elizabeth I (1558-1603), when the state religion again shifted to Protestantism. I argue that the cognitive dissonance created by these seesaw changes of official doctrine necessitated a society in which religious mutability became standard operating procedure. For most early modern men and women it was impossible to navigate between the competing and contradictory dictates of Tudor religion and politics without conforming, dissimulating, or changing important points of conscience and belief. Although early modern theologians and polemicists widely declared religious conformists to be shameless apostates, when we examine specific cases in context it becomes apparent that most individuals found ways to positively rationalize and justify their respective actions. This fraught history continued to have long-term effects on England’s religious, political, and intellectual culture. -

Download File

Ordaining the Disinherited: What Women of Color Clergy Have to Teach Us About Discernment Tamara C. Plummer Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Practical Theology at Union Theological Seminary April 16, 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 3 Conceptual Frame..................................................................................................................... 5 The Episcopal Church ............................................................................................................ 10 Methodology - Story as scripture ............................................................................................. 14 Data: Description and Deconstruction ..................................................................................... 17 Bishop Emma .......................................................................................................................... 18 Rev. Sarai ................................................................................................................................. 25 Rev. Isabella ............................................................................................................................ 31 Rev. Julian ............................................................................................................................... 37 Rev. Juanita ............................................................................................................................ -

Xerox University Microfilms 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 I I

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again - beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

Early-Christianity-Timeline.Pdf

Pagan Empire Christian Empire 100 200 300 400 500 600 700 1 AD Second 'Bishop' of Rome. Pupil of Student of Polycarp. First system- Bishop of Nyssa, brother of Basil. Pope. The Last Father of the Peter. Author of a letter to Corinth, atic theologian, writing volumi- Bishop of Original and sophisticated theologi- model of St Gregory the Church. First of the St John of (1 Clement), the earliest Christian St Clement of Rome nously about the Gospels and the St Irenaeus St Cyprian Carthage. an, writing on Trinitarian doctrine Gregory of Nyssa an ideal Scholastics. Polymath, document outside the NT. church, and against heretics. and the Nicene creed. pastor. Great monk, and priest. Damascus Former disciple of John the Baptist. Prominent Prolific apologist and exegete, the Archbishop of Constantinople, St Leo the Pope. Able administrator in very Archbishop of Seville. Encyclopaedist disciple of Jesus, who became a leader of the most important thinker between Paul brother of Basil. Greatest rhetorical hard times, asserter of the prima- and last great scholar of the ancient St Peter Judean and later gentile Christians. Author of two St Justin Martyr and Origen, writing on every aspect stylist of the Fathers, noted for St Gregory Nazianzus cy of the see of Peter. Central to St Isidore world, a vital link between the learning epistles. Source (?) of the Gospel of Mark. of life, faith and worship. writing on the Holy Spirit. Great the Council of Chalcedon. of antiquity and the Middle Ages. Claimed a knowledge and vision of Jesus independent Pupil of Justin Martyr. Theologian.