Slippery Slopes and Other Consequences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alternative Heroes in Nineteenth-Century Historical Plays

DOI 10.6094/helden.heroes.heros./2014/01/02 Dorothea Flothow 5 Unheroic and Yet Charming – Alternative Heroes in Nineteenth-Century Historical Plays It has been claimed repeatedly that unlike previ- MacDonald’s Not About Heroes (1982) show ous times, ours is a post-heroic age (Immer and the impossibility of heroism in modern warfare. van Marwyck 11). Thus, we also fi nd it diffi cult In recent years, a series of bio-dramas featuring to revere the heroes and heroines of the past. artists, amongst them Peter Shaffer’s Amadeus In deed, when examining historical television se- (1979) and Sebastian Barry’s Andersen’s En- ries, such as Blackadder, it is obvious how the glish (2010), have cut their “artist-hero” (Huber champions of English imperial history are lam- and Middeke 134) down to size by emphasizing pooned and “debunked” – in Blackadder II, Eliz- the clash between personal action and high- abeth I is depicted as “Queenie”, an ill-tempered, mind ed artistic idealism. selfi sh “spoiled child” (Latham 217); her immor- tal “Speech to the Troops at Tilbury” becomes The debunking of great historical fi gures in re- part of a drunken evening with her favourites cent drama is often interpreted as resulting par- (Epi sode 5, “Beer”). In Blackadder the Third, ticularly from a postmodern infl uence.3 Thus, as Horatio Nelson’s most famous words, “England Martin Middeke explains: “Postmodernism sets expects that every man will do his duty”, are triv- out to challenge the occidental idea of enlighten- ialized to “England knows Lady Hamilton is a ment and, especially, the cognitive and episte- virgin” (Episode 2, “Ink and Incapability”). -

Evangelism and Capitalism: a Reparative Account and Diagnosis of Pathogeneses in the Relationship

Digital Commons @ George Fox University Faculty Publications - Portland Seminary Portland Seminary 6-2018 Evangelism and Capitalism: A Reparative Account and Diagnosis of Pathogeneses in the Relationship Jason Paul Clark George Fox University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/gfes Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, and the Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Clark, Jason Paul, "Evangelism and Capitalism: A Reparative Account and Diagnosis of Pathogeneses in the Relationship" (2018). Faculty Publications - Portland Seminary. 132. https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/gfes/132 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Portland Seminary at Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications - Portland Seminary by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EVANGELICALISM AND CAPITALISM A reparative account and diagnosis of pathogeneses in the relationship A thesis submitted to Middlesex University in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Jason Paul Clark Middlesex University Supervised at London School of Theology June 2018 Abstract Jason Paul Clark, “Evangelicalism and Capitalism: A reparative account and diagnosis of pathogeneses in the relationship.” Doctor of Philosophy, Middlesex University, 2018. No sustained examination and diagnosis of problems inherent to the relationship of Evangeli- calism with capitalism currently exists. Where assessments of the relationship have been un- dertaken, they are often built upon a lack of understanding of Evangelicalism, and an uncritical reliance both on Max Weber’s Protestant Work Ethic and on David Bebbington’s Quadrilateral of Evangelical priorities. -

August 13, 2011 Olin Park | Madison, WI 25Years of Great Taste

August 13, 2011 Olin Park | Madison, WI 25years of Great Taste MEMORIES FOR SALE! Be sure to pick up your copy of the limited edition full-color book, The Great Taste of the Midwest: Celebrating 25 Years, while you’re here today. You’ll love reliving each and every year of the festi- val in pictures, stories, stats, and more. Books are available TODAY at the festival souve- nir sales tent, and near the front gate. They will be available online, sometime after the festival, at the Madison Homebrewers and Tasters Guild website, http://mhtg.org. WelcOMe frOM the PresIdent elcome to the Great taste of the midwest! this year we are celebrating our 25th year, making this the second longest running beer festival in the country! in celebration of our silver anniversary, we are releasing the Great taste of the midwest: celebrating 25 Years, a book that chronicles the creation of the festival in 1987W and how it has changed since. the book is available for $25 at the merchandise tent, and will also be available by the front gate both before and after the event. in the forward to the book, Bill rogers, our festival chairman, talks about the parallel growth of the craft beer industry and our festival, which has allowed us to grow to hosting 124 breweries this year, an awesome statistic in that they all come from the midwest. we are also coming close to maxing out the capacity of the real ale tent with around 70 cask-conditioned beers! someone recently asked me if i felt that the event comes off by the seat of our pants, because sometimes during our planning meetings it feels that way. -

The Mercurian Volume 3, No

The Mercurian A Theatrical Translation Review Volume 3, Number 4 Editor: Adam Versényi ISSN 2160-3316 The Mercurian is named for Mercury who, if he had known it, was/is the patron god of theatrical translators, those intrepid souls possessed of eloquence, feats of skill, messengers not between the gods but between cultures, traders in images, nimble and dexterous linguistic thieves. Like the metal mercury, theatrical translators are capable of absorbing other metals, forming amalgams. As in ancient chemistry, the mercurian is one of the five elementary “principles” of which all material substances are compounded, otherwise known as “spirit”. The theatrical translator is sprightly, lively, potentially volatile, sometimes inconstant, witty, an ideal guide or conductor on the road. The Mercurian publishes translations of plays and performance pieces from any language into English. The Mercurian also welcomes theoretical pieces about theatrical translation, rants, manifestos, and position papers pertaining to translation for the theatre, as well as production histories of theatrical translations. Submissions should be sent to: Adam Versényi at [email protected] or by snail mail: Adam Versényi, Department of Dramatic Art, CB# 3230, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3230. For translations of plays or performance pieces, unless the material is in the public domain, please send proof of permission to translate from the playwright or original creator of the piece. Since one of the primary objects of The Mercurian is to move translated pieces into production, no translations of plays or performance pieces will be published unless the translator can certify that he/she has had an opportunity to hear the translation performed in either a reading or another production-oriented venue. -

VPI June 2016

c/o sur la Croix 160, CH - 1020 Renens. www.villageplayers.ch Payments: CCP 10-203 65-1 IBAN: CH71 0900 0000 1002 0365 1 Village Players’ Information (VPI) June 2016 NEXT CLUBNIGHT: VILLAGE PLAYERS’ Annual General Meeting !!!! COME AND FILL THESE SEATS !!!! Thursday 16th June, 2016 At 20h00 Doors open at 19h15 Bar open 19h30 CPO - Centre Pluriculturel d’Ouchy Beau-Rivage 2, 1006 Lausanne PLEASE NOTE IN YOUR DIARIES – AND TELL YOUR FRIENDS AND FELLOW MEMBERS Come and have your say in the running of the club and our activities, and cast your vote for the new Committee. Of the present Committee, the following are willing to stand for (re)election for the following posts: Production Coordinator Daniel Gardini Events Coordinator Mary Couper Secretary Colin Gamage Treasurer Derek Betson Publicity Manager Susan Morris Membership Secretary Dorothy Brooks Technical Manager Ian Griffiths At the moment we have the proposal of Chris Hemmens for the post of Chairman but do not have candidates for the posts of Administrative Director and Business Manager. So before, or latest at, the AGM we will be looking for volunteers to come forward to fill these positions. Brief descriptions of these posts are: ADMINISTRATIVE DIRECTOR: Coordinates the running of the Society, guarantees its efficient administration, assists and deputises for the Chairman. BUSINESS MANAGER: Responsible for forward planning, negotiation for hire of theatres, rooms for productions and events; liaison with appropriate authorities for services, purchase of tickets, front of house, payment of dues and performance rights. THIS IS A VERY IMPORTANT MEETING – WE NEED YOU ALL TO COME ALONG. -

Download Adult Awards Nomination List

Running District Award Order Name Show Society Order 1 Stuart Sephton Baldrick Blackadder II SAM Theatre 2 Anthony Henry General Malchett Blackadder Goes Forth Poulton Drama 3 Roy Washington Danny Brassed Off Blackburn Drama Club 4 Gareth Crawshaw General Melchett Blackadder Goes Forth Carlton Players 5 Best Supporting Cameron Rowe Hugo The Vicar Of Dibley Tyldesley Little Theatre 1 6 Male in a Drama Steven Catterall Peter / Rugby Rep For The Love Of The Game Chorley Amateur Dramatic & Operatic Society 7 Ian Perks Saunders Lend Me A Tenor Crompton Stage Society 8 Bryan Higgins Harry Brassed Off Centenery Theatre Company 10 Marc Goodwin Hubert Bonney It Runs In The Family Whitehaven Theatre Group 11 Steve Dobson George Blackadder Garstang Theatre Group 1 Liz Hudson Pat Green Breaking The Code Sale Nomads 2 Beverley Thompson Baldrick Blackadder Goes Forth Poulton Drama 3 Annie Wildman Tweeney The Admirable Crichton Stage 2, Downham 4 Fran Harmer Doll Common Playhouse Creatures Ashton Hayes Theatre Club Best Supporting 2 5 Cathryn Megan Hughes Alice The Vicar Of Dibley Tyldesley Little Theatre Female in a Drama 6 Emma Bailey Queenie Be My Baby Chorley Amateur Dramatic & Operatic Society 7 Kate Davies Gwendolyn The Importance Of Being Earnest Crompton Stage Society 8 Maria Ames Amy Little Women Centenery Theatre Company 10 Caroline Robertson Eve Holiday Snap Carlisle Green Room Club 3 3 Best Poster Oswaldtwistle Players Four Weddings and an Elvis 1 Tom Guest Cornelius Hackl Hello, Dolly! South Manchester AOS 2 John Rowland Kevin In The Heights -

Come and Get

FRIENDS OF WILL MEMBERSHIP MAGAZINE patterns march 2013 your come and get it! TM patterns march 2013 Volume XL, Number 9 Membership Hotline: 800-898-1065 WILL AM-FM-TV: 217-333-7300 Campbell Hall for Public Telecommunication 300 N. Goodwin Ave., Urbana, IL 61801-2316 New ways of coming together Mailing List Exchange By Lisa Bralts, Marketing Director Donor records are proprietary and confidential. WILL will not sell, rent or trade its donor lists. If you’ve been to Urbana’s Market Patterns at the Square—our area’s largest Friends of WILL Membership Magazine Editor: Cyndi Paceley farmers market—you know that it Art Director: Michael Thomas seems like the entire community Designer: Laura Adams-Wiggs attends. The Market is an area Patterns (USPS 092-370) is published monthly at Campbell Hall for jewel—a place where people come Public Telecommunication, 300 N. Goodwin Ave., Urbana, IL 61801- 2316 by and for the Friends of WILL. Membership dues for the together and connect with farmers, Friends of WILL begin at $40 per year, with $7.62 designated for 12 their food and with each other. issues of Patterns. The remainder of membership dues is used for the support of the activities of Illinois Public Media at the University As I neared the end of my tenure as the Market’s of Illinois through the Friends of WILL. Periodicals postage paid at Urbana, Illinois, and additional mailing offices. director last September and told patrons about Postmaster: Send address changes to Patterns, my upcoming adventure as Illinois Public Media’s Campbell Hall for Telecommunication, marketing director, they got excited. -

Disabling Comedy: “Only When We Laugh!”

Disabling Comedy: “Only When We Laugh!” Dr. Laurence Clark, North West Disability Arts Forum (Paper presented at the ‘Finding the Spotlight’ Conference, Liverpool Institute for the Performing Arts, 30th May 2003) Abstract Traditionally comedy involving disabled people has extracted humour from people’s impairments – i.e. a “functional limitation”. Examples range from Shakespeare’s ‘fool’ character and Elizabethan joke books to characters in modern TV sitcoms. Common arguments for the use of such disempowering portrayals are that “nothing is meant by them” and that “people should be able to laugh at themselves”. This paper looks at the effects of such ‘disabling comedy’. These include the damage done to the general public’s perceptions of disabled people, the contribution to the erosion of a disabled people’s ‘identity’ and how accepting disablist comedy as the ‘norm’ has served to exclude disabled writers / comedians / performers from the profession. 1. Introduction Society has been deriving humour from disabled people for centuries. Elizabethan joke books were full of jokes about disabled people with a variety of impairments. During the 17th and 18th centuries, keeping 'idiots' as objects of humour was common among those who had the money to do so, and visits to Bedlam and other 'mental' institutions were a typical form of entertainment (Barnes, 1992, page 14). Bilken and Bogdana (1977) identified “the disabled person as an object of ridicule” as one of the ten media stereotypes of disabled people. Apart from ridicule, disabled people have been largely excluded from the world of comedy in the past. For example, in the eighties American stand-up comedian George Carlin was arrested whilst doing his act for swearing in front of young disabled people. -

Historical Inquiry in an Informal Fan Community: Online Source Usage and the TV Show the Tudors

Journal of the Learning Sciences ISSN: 1050-8406 (Print) 1532-7809 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/hlns20 Historical Inquiry in an Informal Fan Community: Online Source Usage and the TV Show The Tudors Jolie Christine Matthews To cite this article: Jolie Christine Matthews (2016) Historical Inquiry in an Informal Fan Community: Online Source Usage and the TV Show The Tudors, Journal of the Learning Sciences, 25:1, 4-50, DOI: 10.1080/10508406.2015.1112285 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10508406.2015.1112285 Accepted author version posted online: 29 Oct 2015. Published online: 29 Oct 2015. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 420 View related articles View Crossmark data Citing articles: 4 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=hlns20 Download by: [Northwestern University] Date: 02 March 2017, At: 05:25 THE JOURNAL OF THE LEARNING SCIENCES, 25: 4–50, 2016 Copyright © Taylor & Francis Group, LLC ISSN: 1050-8406 print / 1532-7809 online DOI: 10.1080/10508406.2015.1112285 LEARNING OUTSIDE OF SCHOOL STRAND Historical Inquiry in an Informal Fan Community: Online Source Usage and the TV Show The Tudors Jolie Christine Matthews Department of Learning Sciences Northwestern University This article examines an informal online community dedicated to The Tudors, a his- torical television show, and the ways in which its members engaged with a variety of sources in their discussions of the drama’s real-life past. Data were collected over a 5-month period. -

Black Adder II: “Bells”

Black Adder II: “Bells” UK TV sitcom: 1985 : dir. : BBC : ? x ? min prod: : scr: Richard Curtis & Ben Elton : dir.ph.: ……….…………………………………………………………………………………………………… Rowan Atkinson; Miranda Richardson; Stephen Fry; Rik Mayall Ref: Pages Sources Stills Words Ω 8 M Copy on VHS Last Viewed 5659 1 0 0 453 No April 2002 In successive seasons this sitcom followed the fortunes of the Blackadder dynasty at different epochs of British history, the second (and best) series set at the court of Elizabeth I (Miranda Richardson). Blackadder himself (Atkinson) is a callous, world-weary courtier with a dungheap of a personal servant, Baldrick, and a witless aristocratic sidekick. In this episode a young woman comes to seek service with him disguised as a boy, rather than turn to prostitution to prevent her aged parent being turned onto the streets. Blackadder finds himself uncomfortably drawn to this page boy, “Bob”, seeks medical help and finally consults an old mystic woman for a cure. Nothing will mitigate his lust for the lad, but his masculinity is salvaged when “Bob” finally comes out to him as female. Ecstatic, he makes wedding plans at once, only to have his bride snatched away at the altar by a hellraising sea captain and ladykiller (Rik Mayall). This might as easily have been written for Frankie Howerd’s bawdy “Up Pompeii” series, except that in the intervening decade it had ceased to be kosher to make lewd fun out of men screwing boys. In the seventies “Monty Python” contained frequent risqué allusions to pederasty without anyone raising a disapproving voice, but by 1985 it had become a topic decidedly off-limits to humour. -

Translating Puns

TRANSLATING PUNS A STUDY OF A FEW EXAMPLES FROM BRITISH SERIES, BOOKS AND NEWSPAPERS MEMOIRE DE MASTER 1 ETUDES ANGLOPHONES AGNES POTIER-MURPHY Sous la direction de Mme Nathalie VINCENT-ARNAUD Année universitaire 2015-2016 Acknowledgements Firstly, I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my research director, Nathalie Vincent-Arnaud, for her continuous support, for her patience, motivation, and invaluable insights. I would also like to thank my assessor, Henri Le Prieult, for accepting to review my work and for all the inspiration I drew from his classes. Finally, I need to thank my family for supporting me throughout the writing of the present work. 1 Table of Contents 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 3 2. Theoretical Background .................................................................................................................. 5 2.1. What is Humour? .................................................................................................................... 5 2.2. Linguistic Humour: Culture and Metaphor ............................................................................. 7 2.3. Puns: a very specific humorous device ................................................................................... 9 2.4. Humour theories applied to translation ............................................................................... 10 3. Case study .................................................................................................................................... -

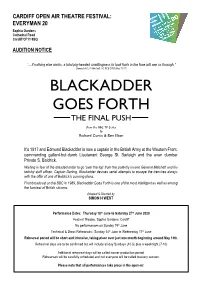

Blackadder Goes Forth the Final Push

CARDIFF OPEN AIR THEATRE FESTIVAL: EVERYMAN 20 Sophia Gardens Cathedral Road Cardiff CF11 9SQ AUDITION NOTICE “... if nothing else works, a total pig-headed unwillingness to look facts in the face will see us through.” General A.C.H. Melchett, VC KCB DSO (May 1917) BLACKADDER GOES FORTH THE FINAL PUSH from the BBC TV Series by Richard Curtis & Ben Elton It's 1917 and Edmund Blackadder is now a captain in the British Army at the Western Front, commanding gallant-but-dumb Lieutenant George St. Barleigh and the even dumber Private S. Baldrick. Waiting in fear of the dreaded order to go 'over the top' from the patently insane General Melchett and his twitchy staff officer, Captain Darling, Blackadder devises serial attempts to escape the trenches always with the offer of one of Baldrick's cunning plans. First broadcast on the BBC in 1989, Blackadder Goes Forth is one of the most intelligent as well as among the funniest of British sitcoms. Adapted & Directed by SIMON H WEST Performance Dates: Thursday 18th June to Saturday 27th June 2020 Festival Theatre, Sophia Gardens, Cardiff No performances on Sunday 19th June Technical & Dress Rehearsals: Sunday 14th June to Wednesday 17th June Rehearsal period will be short and intensive, taking place over just one month beginning around May 14th. Rehearsal days are to be confirmed but will include all day Sundays (10-5) plus a weeknight (7-10) Additional rehearsal days will be called nearer production period. Rehearsals will be carefully scheduled and not everyone will be called to every session. Please note that all performances take place in the open-air.