Mcguinness2017.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Downloaded4.0 License

New West Indian Guide 94 (2020) 39–74 nwig brill.com/nwig A Disagreeable Text The Uncovered First Draft of Bryan Edwards’s Preface to The History of the British West Indies, c. 1792 Devin Leigh Department of History, University of California, Davis, Davis, CA, USA [email protected] Abstract Bryan Edwards’s The History of the British West Indies is a text well known to histori- ans of the Caribbean and the early modern Atlantic World. First published in 1793, the work is widely considered to be a classic of British Caribbean literature. This article introduces an unpublished first draft of Edwards’s preface to that work. Housed in the archives of the West India Committee in Westminster, England, this preface has never been published or fully analyzed by scholars in print. It offers valuable insight into the production of West Indian history at the end of the eighteenth century. In particular, it shows how colonial planters confronted the challenges of their day by attempting to wrest the practice of writing West Indian history from their critics in Great Britain. Unlike these metropolitan writers, Edwards had lived in the West Indian colonies for many years. He positioned his personal experience as being a primary source of his historical legitimacy. Keywords Bryan Edwards – West Indian history – eighteenth century – slavery – abolition Bryan Edwards’s The History, Civil and Commercial, of the British Colonies in the West Indies is a text well known to scholars of the Caribbean (Edwards 1793). First published in June of 1793, the text was “among the most widely read and influential accounts of the British Caribbean for generations” (V. -

Antigua and Barbuda an Annotated Critical Bibliography

Antigua and Barbuda an annotated critical bibliography by Riva Berleant-Schiller and Susan Lowes, with Milton Benjamin Volume 182 of the World Bibliographical Series 1995 Clio Press ABC Clio, Ltd. (Oxford, England; Santa Barbara, California; Denver, Colorado) Abstract: Antigua and Barbuda, two islands of Leeward Island group in the eastern Caribbean, together make up a single independent state. The union is an uneasy one, for their relationship has always been ambiguous and their differences in history and economy greater than their similarities. Barbuda was forced unwillingly into the union and it is fair to say that Barbudan fears of subordination and exploitation under an Antiguan central government have been realized. Barbuda is a flat, dry limestone island. Its economy was never dominated by plantation agriculture. Instead, its inhabitants raised food and livestock for their own use and for provisioning the Antigua plantations of the island's lessees, the Codrington family. After the end of slavery, Barbudans resisted attempts to introduce commercial agriculture and stock-rearing on the island. They maintained a subsistence and small cash economy based on shifting cultivation, fishing, livestock, and charcoal-making, and carried it out under a commons system that gave equal rights to land to all Barbudans. Antigua, by contrast, was dominated by a sugar plantation economy that persisted after slave emancipation into the twentieth century. Its economy and goals are now shaped by the kind of high-impact tourism development that includes gambling casinos and luxury hotels. The Antiguan government values Barbuda primarily for its sparsely populated lands and comparatively empty beaches. This bibliography is the only comprehensive reference book available for locating information about Antigua and Barbuda. -

Piracy, Illicit Trade, and the Construction of Commercial

Navigating the Atlantic World: Piracy, Illicit Trade, and the Construction of Commercial Networks, 1650-1791 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University by Jamie LeAnne Goodall, M.A. Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2016 Dissertation Committee: Margaret Newell, Advisor John Brooke David Staley Copyright by Jamie LeAnne Goodall 2016 Abstract This dissertation seeks to move pirates and their economic relationships from the social and legal margins of the Atlantic world to the center of it and integrate them into the broader history of early modern colonization and commerce. In doing so, I examine piracy and illicit activities such as smuggling and shipwrecking through a new lens. They act as a form of economic engagement that could not only be used by empires and colonies as tools of competitive international trade, but also as activities that served to fuel the developing Caribbean-Atlantic economy, in many ways allowing the plantation economy of several Caribbean-Atlantic islands to flourish. Ultimately, in places like Jamaica and Barbados, the success of the plantation economy would eventually displace the opportunistic market of piracy and related activities. Plantations rarely eradicated these economies of opportunity, though, as these islands still served as important commercial hubs: ports loaded, unloaded, and repaired ships, taverns attracted a variety of visitors, and shipwrecking became a regulated form of employment. In places like Tortuga and the Bahamas where agricultural production was not as successful, illicit activities managed to maintain a foothold much longer. -

So2 and Wine: a Review

OIV COLLECTIVE EXPERTISE DOCUMENT SO2 AND WINE: A REVIEW SO2 AND WINE: A REVIEW 1 MARCH 2021 OIV COLLECTIVE EXPERTISE DOCUMENT SO2 AND WINE: A REVIEW WARNING This document has not been submitted to the step procedure for examining resolutions and cannot in any way be treated as an OIV resolution. Only resolutions adopted by the Member States of the OIV have an official character. This document has been drafted in the framework of Expert Group “Food safety” and revised by other OIV Commissions. This document, drafted and developed on the initiative of the OIV, is a collective expert report. © OIV publications, 1st Edition: March 2021 (Paris, France) ISBN 978-2-85038-022-8 OIV - International Organisation of Vine and Wine 35, rue de Monceau F-75008 Paris - France www.oiv.int 2 MARCH 2021 OIV COLLECTIVE EXPERTISE DOCUMENT SO2 AND WINE: A REVIEW SCOPE The group of experts « Food safety » of the OIV has worked extensively on the safety assessment of different compounds found in vitivinicultural products. This document aims to gather more specific information on SO2. This document has been prepared taking into consideration the information provided during the different sessions of the group of experts “Food safety” and information provided by Member States. Finally, this document, drafted and developed on the initiative of the OIV, is a collective expert report. This review is based on the help of scientific literature and technical works available until date of publishing. COORDINATOR OIV - International Organisation of Vine and Wine AUTHORS Dr. Creina Stockley (AU) Dr. Angelika Paschke-Kratzin (DE) Pr. -

Redescription of Hypoatherina Valenciennei and Its Relationships to Other Species of Atherinidae in the Pacific and Indian Oceans

Japanese Journal of Ichthyology 魚 類 学 雑 誌 Vol. 35, No. 2 1988 35 巻 2 号 1988年 Redescription of Hypoatherina valenciennei and its Relationships to Other Species of Atherinidae in the Pacific and Indian Oceans Walter Ivantsoff and Maurice Kottelat (Received December 23, 1986) Abstract A review of Tirant's collections and examination of types has resulted in the reidentifica- tion of Haplocheilus argyrotaenia Tirant as Hypoatherina valenciennei (Bleeker) which is found throughout the southwestern Pacific and as far north as Japan. The taxonomic status of H. valenciennei is clarified and Bleeker's emendation of the original specific epithet valenciennei to valenciennesi is rejected. The systematic position of this species is difficult to determine since H. valenciennei shows affinities with both Hypoatherina and Atherinomorus. In the light of the present knowledge, Bleeker's species appears to have greater affinities with Hypoatherina and is therefore placed in this genus. Recent reexamination of the types of Haplo- 1983). The genus Hypoatherina as defined by cheilus argyrotaenia Tirant, 1883, (unaccepted and Ivantsoff (1978) includes all those species with misspelt emendation of Haplochilus Agassiz, 1846, moderately long dorsal process of premaxilla but for Aplocheilus McClelland, 1839) has prompted not longer than eye diameter, lateral process of us to review the status of Hypoatherina valenciennei premaxilla short and broad, lower jaw coronoid (Bleeker, 1853a) which is considered to be the process highly elevated, distinct notch (sensory senior synonym of Tirant's species (thought by canal opening) in posterior margin of anterior him to be an aplocheilid). Although the systema- bony edge of preopercle near its lower corner, tic position of the Pacific atherinids is yet to be body slender and subcylindrical, midlateral band resolved, work to that end has already begun. -

American Eel Anguilla Rostrata

COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the American Eel Anguilla rostrata in Canada SPECIAL CONCERN 2006 COSEWIC COSEPAC COMMITTEE ON THE STATUS OF COMITÉ SUR LA SITUATION ENDANGERED WILDLIFE DES ESPÈCES EN PÉRIL IN CANADA AU CANADA COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC 2006. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the American eel Anguilla rostrata in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. x + 71 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm). Production note: COSEWIC would like to acknowledge V. Tremblay, D.K. Cairns, F. Caron, J.M. Casselman, and N.E. Mandrak for writing the status report on the American eel Anguilla rostrata in Canada, overseen and edited by Robert Campbell, Co-chair (Freshwater Fishes) COSEWIC Freshwater Fishes Species Specialist Subcommittee. Funding for this report was provided by Environment Canada. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: (819) 997-4991 / (819) 953-3215 Fax: (819) 994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Évaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur l’anguille d'Amérique (Anguilla rostrata) au Canada. Cover illustration: American eel — (Lesueur 1817). From Scott and Crossman (1973) by permission. ©Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada 2004 Catalogue No. CW69-14/458-2006E-PDF ISBN 0-662-43225-8 Recycled paper COSEWIC Assessment Summary Assessment Summary – April 2006 Common name American eel Scientific name Anguilla rostrata Status Special Concern Reason for designation Indicators of the status of the total Canadian component of this species are not available. -

Sweeteners Georgia Jones, Extension Food Specialist

® ® KFSBOPFQVLCB?O>PH>¨ FK@LIKUQBKPFLK KPQFQRQBLCDOF@RIQROB>KA>QRO>IBPLRO@BP KLTELT KLTKLT G1458 (Revised May 2010) Sweeteners Georgia Jones, Extension Food Specialist Consumers have a choice of sweeteners, and this NebGuide helps them make the right choice. Sweeteners of one kind or another have been found in human diets since prehistoric times and are types of carbohy- drates. The role they play in the diet is constantly debated. Consumers satisfy their “sweet tooth” with a variety of sweeteners and use them in foods for several reasons other than sweetness. For example, sugar is used as a preservative in jams and jellies, it provides body and texture in ice cream and baked goods, and it aids in fermentation in breads and pickles. Sweeteners can be nutritive or non-nutritive. Nutritive sweeteners are those that provide calories or energy — about Sweeteners can be used not only in beverages like coffee, but in baking and as an ingredient in dry foods. four calories per gram or about 17 calories per tablespoon — even though they lack other nutrients essential for growth and health maintenance. Nutritive sweeteners include sucrose, high repair body tissue. When a diet lacks carbohydrates, protein fructose corn syrup, corn syrup, honey, fructose, molasses, and is used for energy. sugar alcohols such as sorbitol and xytilo. Non-nutritive sweet- Carbohydrates are found in almost all plant foods and one eners do not provide calories and are sometimes referred to as animal source — milk. The simpler forms of carbohydrates artificial sweeteners, and non-nutritive in this publication. are called sugars, and the more complex forms are either In fact, sweeteners may have a variety of terms — sugar- starches or dietary fibers.Table I illustrates the classification free, sugar alcohols, sucrose, corn sweeteners, etc. -

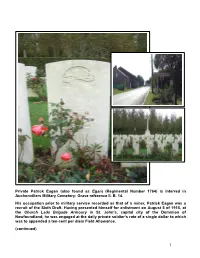

Private Patrick Eagan (Also Found As Egan) (Regimental Number 1764) Is Interred in Auchonvillers Military Cemetery: Grave Reference II

Private Patrick Eagan (also found as Egan) (Regimental Number 1764) is interred in Auchonvillers Military Cemetery: Grave reference II. B. 14. His occupation prior to military service recorded as that of a miner, Patrick Eagan was a recruit of the Sixth Draft. Having presented himself for enlistment on August 5 of 1915, at the Church Lads Brigade Armoury in St. John’s, capital city of the Dominion of Newfoundland, he was engaged at the daily private soldier’s rate of a single dollar to which was to appended a ten-cent per diem Field Allowance. (continued) 1 Just one day after having enlisted, on August 6 he was to return to the CLB Armoury on Harvey Road. On this second occasion Patrick Eagan was to undergo a medical examination, a procedure which was to pronounce him as being…Fit for Foreign Service. And it must have been only hours afterwards again that there then came the final formality of his enlistment: attestation. On the same August 6 he pledged his allegiance to the reigning monarch, George V, at which moment Patrick Eagan thus became…a soldier of the King. A further, and lengthier, waiting-period was now in store for the recruits of this draft, designated as ‘G’ Company, before they were to depart from Newfoundland for…overseas service. Private Eagan, Regimental Number 1764, was not to be again called upon until October 27, after a period of twelve weeks less two days. Where he was to spend this intervening time appears not to have been recorded although he possibly returned temporarily to his work and perhaps would have been able to spend time with family and friends in the Bonavista Bay community of Keels – but, of course, this is only speculation. -

American Eel (Anguilla Rostrata )

American Eel (Anguilla rostrata ) Abstract The American eel ( Anguilla rostrata ) is a freshwater eel native in North America. Its smooth, elongated, “snake-like” body is one of the most noted characteristics of this species and the other species in this family. The American Eel is a catadromous fish, exhibiting behavior opposite that of the anadromous river herring and Atlantic salmon. This means that they live primarily in freshwater, but migrate to marine waters to reproduce. Eels are born in the Sargasso Sea and then as larvae and young eels travel upstream into freshwater. When they are fully mature and ready to reproduce, they travel back downstream into the Sargasso Sea,which is located in the Caribbean, east of the Bahamas and north of the West Indies, where they were born (Massie 1998). This species is most common along the Atlantic Coast in North America but its range can sometimes even extend as far as the northern shores of South America (Fahay 1978). Context & Content The American Eel belongs in the order of Anguilliformes and the family Anguillidae, which consist of freshwater eels. The scientific name of this particular species is Anguilla rostrata; “Anguilla” meaning the eel and “rostrata” derived from the word rostratus meaning long-nosed (Ross 2001). General Characteristics The American Eel goes by many common names; some names that are more well-known include: Atlantic eel, black eel, Boston eel, bronze eel, common eel, freshwater eel, glass eel, green eel, little eel, river eel, silver eel, slippery eel, snakefish and yellow eel. Many of these names are derived from the various colorations they have during their lifetime. -

HIST233: the ATLANTIC WORLD, 1600‑1850 CRN 9521 Contents

1 School of History, Philosophy, Political Science and International Relations History 2007 Trimester 2 HIST233: THE ATLANTIC WORLD, 1600‑1850 CRN 9521 Contents page Course guide ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 4 Trimester outline ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 13 Lecture guide ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 16 Tutorial guide ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 17 Essay writing: general instructions ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 26 Assessment 1: Map quiz ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 38 Assessment 2: Article review ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 39 Assessment 3: Research essay ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 53 Model 200level essay ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 55 Assessment 4: Terms test ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 64 Lecture readings ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 66 Essay writing reading ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 169 Tutorial readings ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 173 Maps and supplementary materials ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 259 Victoria University of Wellington, History Programme, HIST233: -

Early Puritanism in the Southern and Island Colonies

Early Puritanism in the Southern and Island Colonies BY BABETTE M. LEVY Preface NE of the pleasant by-products of doing research O work is the realization of how generously help has been given when it was needed. The author owes much to many people who proved their interest in this attempt to see America's past a little more clearly. The Institute of Early American History and Culture gave two grants that enabled me to devote a sabbatical leave and a summer to direct searching of colony and church records. Librarians and archivists have been cooperative beyond the call of regular duty. Not a few scholars have read the study in whole or part to give me the benefit of their knowledge and judgment. I must mention among them Professor Josephine W, Bennett of the Hunter College English Department; Miss Madge McLain, formerly of the Hunter College Classics Department; the late Dr. William W. Rockwell, Librarian Emeritus of Union Theological Seminary, whose vast scholarship and his willingness to share it will remain with all who knew him as long as they have memories; Professor Matthew Spinka of the Hartford Theological Sem- inary; and my mother, who did not allow illness to keep her from listening attentively and critically as I read to her chapter after chapter. All students who are interested 7O AMERICAN ANTIQUARIAN SOCIETY in problems concerning the early churches along the Atlantic seaboard and the occupants of their pulpits are indebted to the labors of Dr. Frederick Lewis Weis and his invaluable compendiums on the clergymen and parishes of the various colonies. -

Bitasion Les Habitations-Plantations Constituent Le Creuset Historique Et Symbolique Où Fut Fondu L’Alliage Original Que Sont Les Cultures Antillaises

Kelly & Bérard Ouvrage dirigé par Bitasion Les habitations-plantations constituent le creuset historique et symbolique où fut fondu l’alliage original que sont les cultures antillaises. Elles sont le berceau des sociétés créoles contemporaines qui y ont puisé tant leur forte parenté que leur Bitasion - Archéologie des habitations-plantations des Petites Antilles diversité. Leur étude a été précocement le terrain de prédilection des historiens. Les archéologues antillanistes se consacraient alors plus volontiers à l’étude des sociétés précolombiennes. Ainsi, en dehors des travaux pionniers de J. Handler et F. Lange à la Barbade, c’est surtout depuis la fin des années 1980 qu’un véritable développement de l’archéologie des habitations-plantations antillaises a pu être observé. Les questions pouvant être traitées par l’archéologie des habitations-plantations sont extrêmement riches et multiples et ne sauraient être épuisées par la publication d’un unique ouvrage. Les différents chapitres qui composent ce livre dirigé par K. Kelly et B. Bérard n’ont pas vocation à tendre à l’exhaustivité. Ils nous semblent, par contre, être représentatifs, par la variété des questions abordée et la diversité des angles d’approche, de la dynamique actuelle de ce champ de la recherche. Cette diversité est évidemment liée à celle des espaces concernés: les habitations-plantations de cinq îles des Petites Antilles : Antigua, la Guadeloupe, la Dominique, la Martinique et la Barbade sont ici étudiées. Elle est aussi, au sein d’un même espace, due à la cohabitation de différentes pratiques universitaires. Nous espérons que cet ouvrage, tout en diffusant une information jusqu’à présent trop dispersée, sera le point de départ de nouveaux travaux.